The architect Louis Sullivan coined the phrase “form ever follows function” in an essay laying out the aesthetic laws for designing a new and exciting phenomenon of the late 19th century, the office block; his fundamental principle was that “the shape, form, outward expression, design...of the tall office building should in the very nature of things follow the functions of the building, and that where the function does not change, the form is not to change” (Sullivan 1896: 408). I use it here as a starting point from which to unpick the complex and changing relationships between writing and its material supports during the Aegean Bronze Age, with the basic hypothesis that the shape of objects which bear writing, the Bronze Age ‘office stationery’ so to speak, derives from the use to which they, object + writing, are put and the shape changes as this purpose changes.

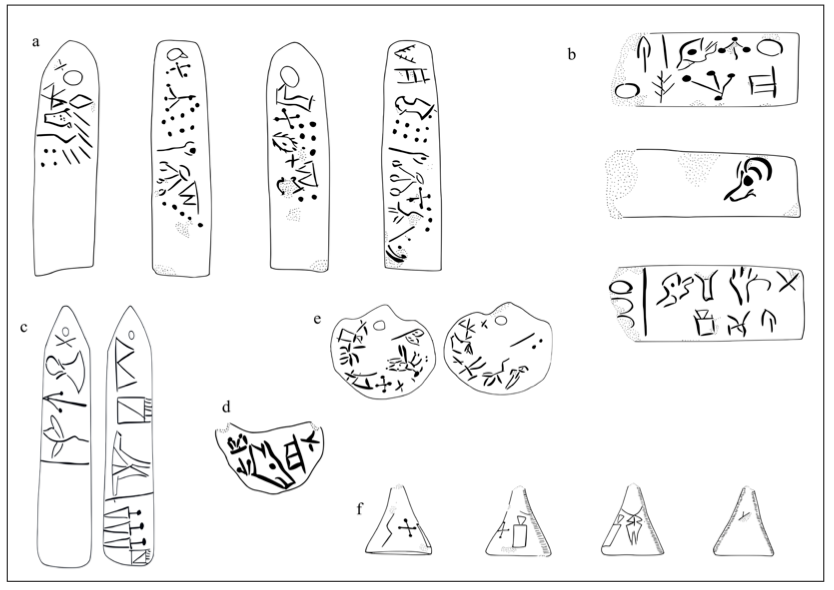

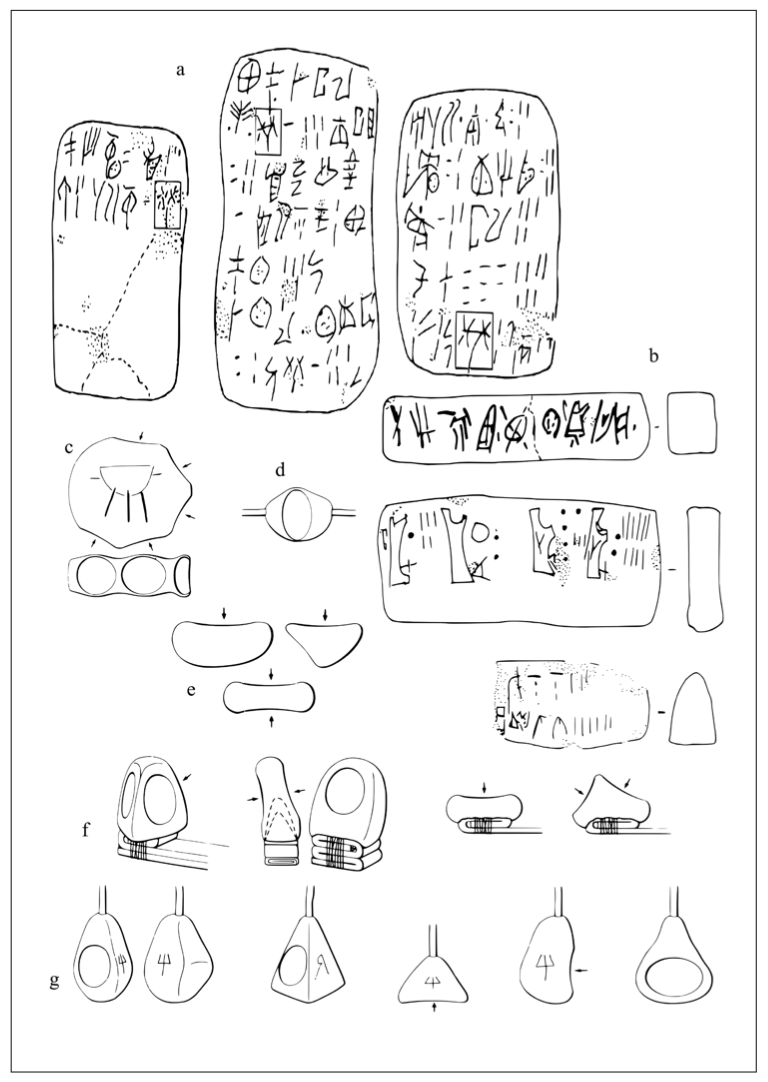

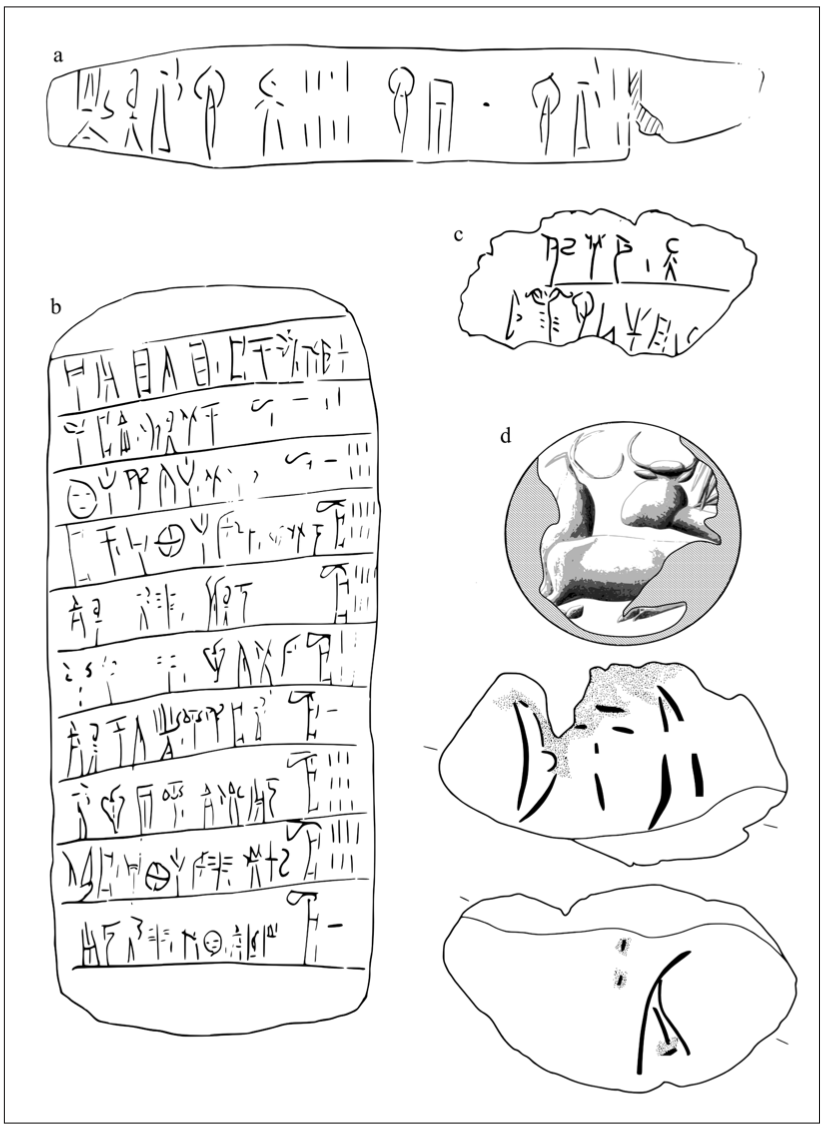

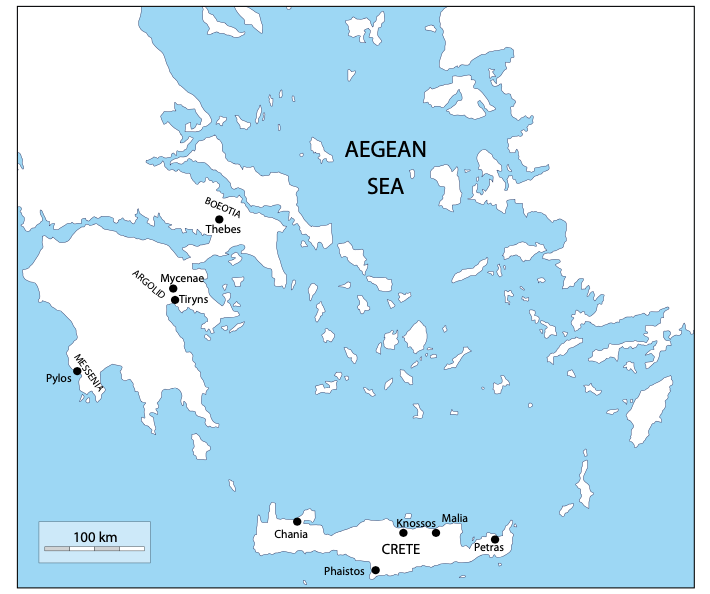

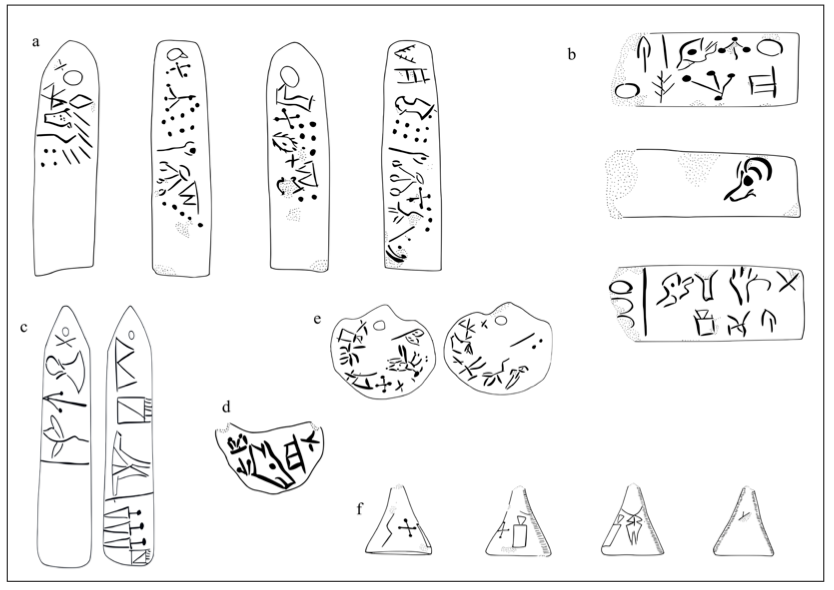

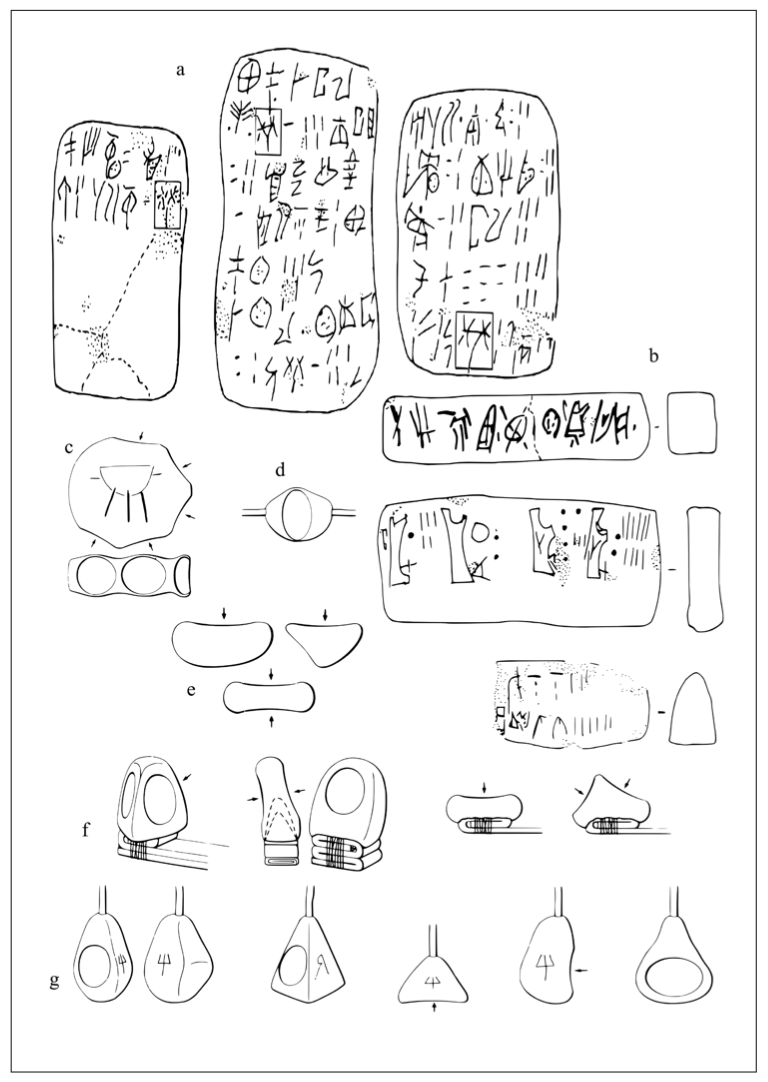

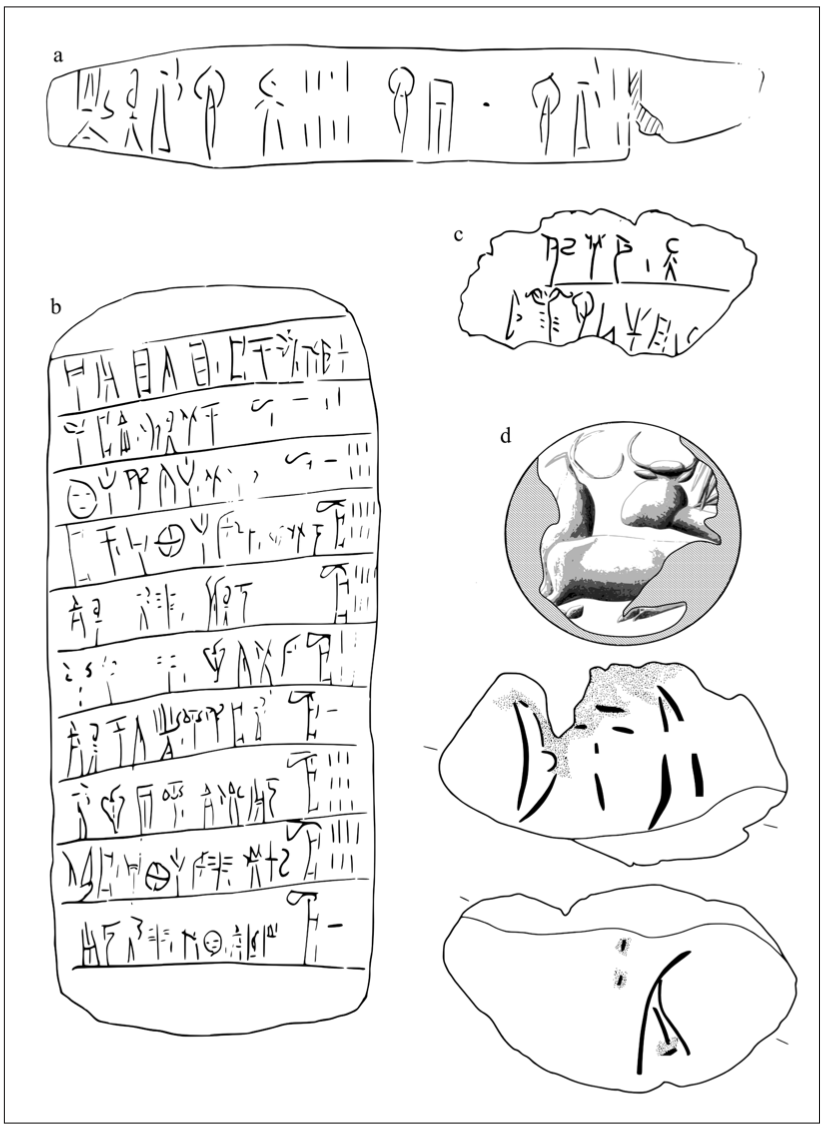

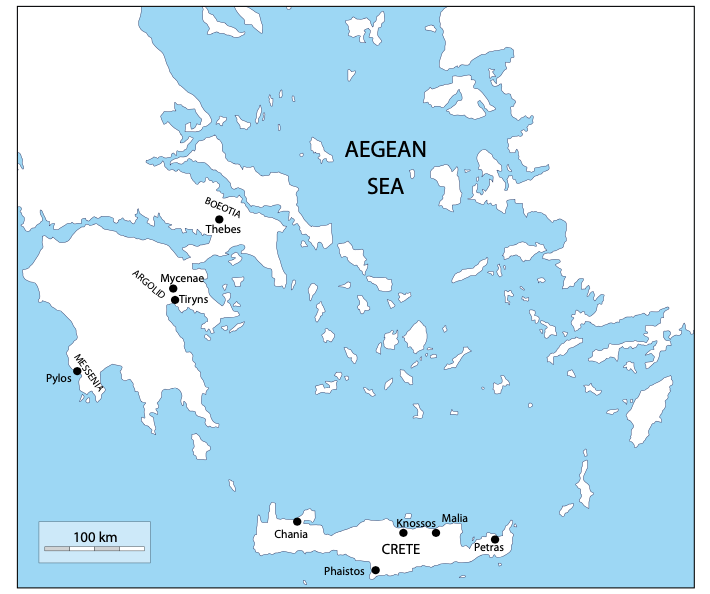

Following an overview of the datasets included in this study, I review the use of writing supports for each of the three main Aegean scripts, Cretan Hieroglyphic (Figure 1a–f), Linear A (Figure 2a–g) and Linear B (Figure 3a–d), before focussing on Linear A practice to consider how the form and function of different kinds of writing-bearing object interrelate within a particular chronological period. As will become clear, a long time period is covered here, at least 500 years or so, but at points the evidence is embarrassingly meagre and inevitably there are large gaps in our understanding of how, when and where writing is being used. For all these reasons, it is appropriate to keep the following discussion rather general and tentative.

Figure 1: Key Cretan Hieroglyphic document shapes (not to scale). a) Four-sided bar, Knossos Hh (04) 03 (Olivier and Godart 1996: 111); b) Tablet, Malia Palace MA/P Hi 02: front, side and back faces shown (Olivier and Godart 1996: 174); c) Label, Malia Quartier Mu MA/M Hf (04) 01 (Olivier and Godart 1996: 140); d) Crescent, Knossos Ha (04) 01: face gamma shown, with CH inscription (Olivier and Godart 1996: 78); e) Medallion, Knossos He (04) 06 (Olivier and Godart 1996: 92); f) Cone, Malia Quartier Mu MA/M Hd (02) (Olivier and Godart 1996: 126).

Figure 2: Key Linear A document shapes (not to scale). a) Different shapes and layouts of LA tablets: all deal with commodity AB 30, figs, ideogram marked with rectangle (Schoep 2002a: 95); b) Four-sided bar, oblong tablet and three-sided bar: inscribed face and end profile shown (Schoep 2002a: 17); c) Roundel: arrows indicate seal impression (Hallager 1996: 23); d) Two-hole hanging nodule (Hallager 1996: 23); e) Noduli: arrows indicate seal impression (Hallager 1996: 23); f) Flat-based nodules: arrows indicate seal impression (Hallager 1996: 23); g) Single- hole hanging nodules: arrows indicate seal impression (Hallager 1996: 23).

Figure 3: Key Linear B document shapes (not to scale). a) ‘Palm-leaf tablet’, Pylos Aa 98; b) Page- shaped tablet, Pylos Cn 4; c) Label, Pylos Wa 114; d) Gable-shaped hanging nodule, Pylos Wr 1328: lines indicate string holes (Pini 1997: pl. 25) (Figures 3a–c after Bennet et al. 1955: 14, 1 and 15, respectively). © 1955 Princeton University Press, 1983 renewed PUP. Reprinted by permission of Princeton University Press.

Figure 4: Map showing key sites referred to in text. Base map courtesy of John Bennet.