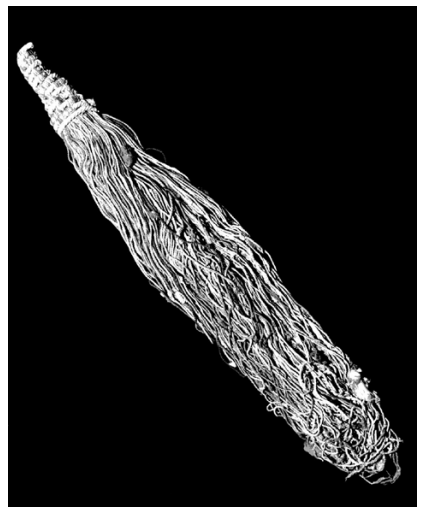

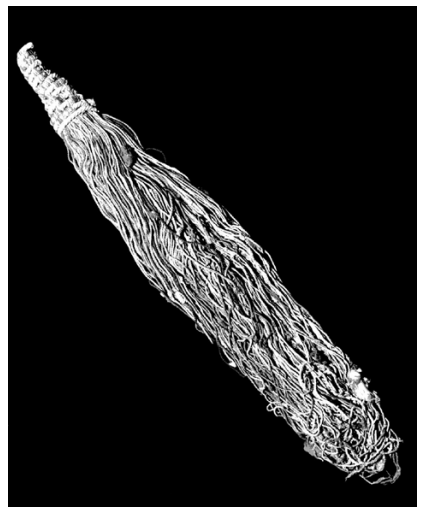

The most complex system of writing (using the word in a broad sense) that Andean peoples possessed before the Spanish invasion of 1532 was the cord- and knot-based medium called khipu (Quechua) or quipu (Spanish). The material makeup of khipu is a story of variation over time, with some longue durée continuities. Khipu had a brief, spectacularly productive heyday as the official medium of the Inka state (established some time during the 15th century ce until 1532 ce). The great majority of all the 600-odd more or less complete khipus held in museums and accessible private collections are catalogued as imperial Inka artifacts, but new radiocarbon results show that some date from the Spanish colony (Cherkinsky and Urton, forthcoming). The Ethnologisches Museum in Berlin and the American Museum of Natural History in New York have the largest collections. Online offerings suggest that an unknown number of them (some fake) are in other hands. Inka khipus were largely standardized in format and material content (Figure 1).

But Inkas are not the only principals in this story. The cord medium underwent a long, varied evolution both before and after khipus’ brief Inka florescence. Both pre- and post-Inka khipus differed widely from Inka ones in physical substance and form. This chapter consists of a historical and a functional section. In the first half I discuss material attributes of Inka, pre-Inka, and post-Inka khipus, respectively, with emphasis on change. By contrast, in the second half of this chapter I emphasize material continuity: material traits that make a khipu a khipu, and how they affect culture as lived through inscription. For the spatial distribution of the evidence discussed, see the map in Figure 2.

Figure 1: Khipu demonstrates repeating colour sequence. 64-19-1-1-6-2 of the Musée de l’Homme (now in Musée du Quai Branly).

Figure 2: Map showing main locations mentioned in the text.

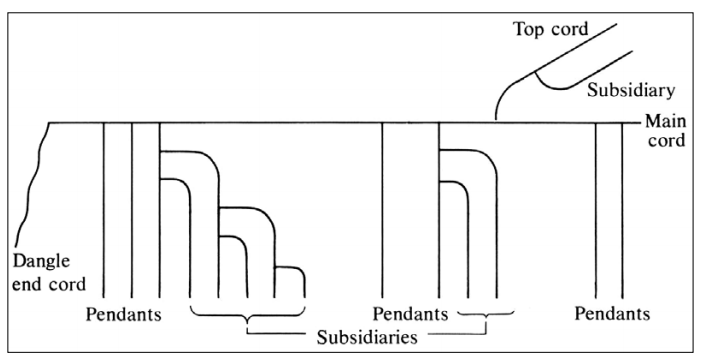

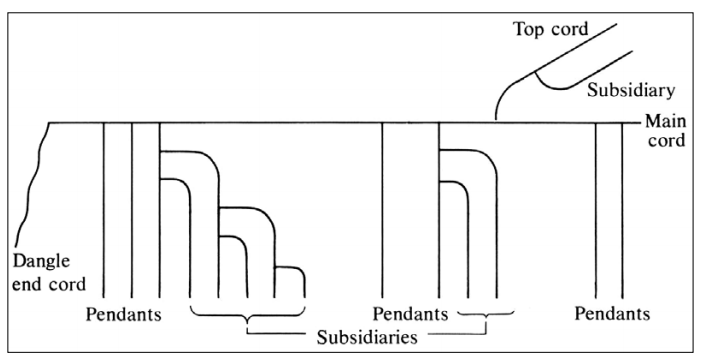

Figure 3: Basic khipu terminology and structure (Ascher and Ascher 1997: 12, fig. 2.7). By permission of Marcia Ascher and Robert Ascher.

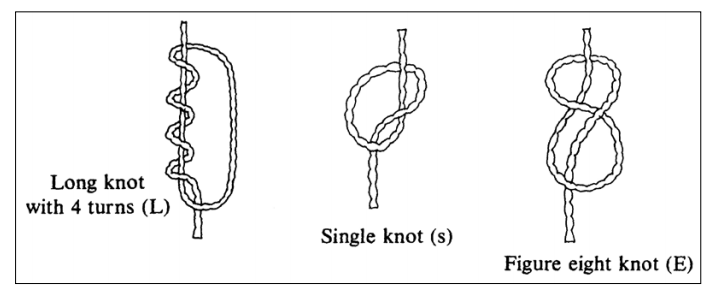

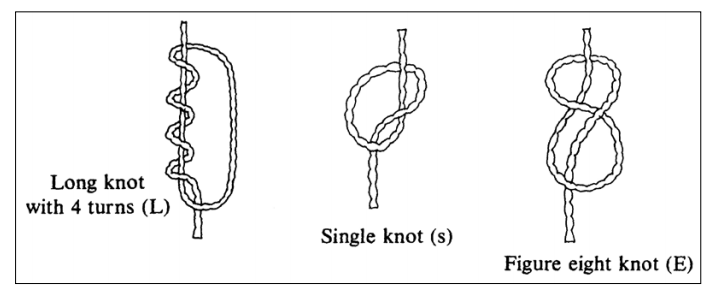

Figure 4: Three common knots used in Inka khipus: Left: Inka long knot of value four, used in units place; center, simple (s) knot; right, figure-eight (E) knot (Ascher and Ascher 1997: 29, fig. 2.11). By permission of Marcia Ascher and Robert Ascher

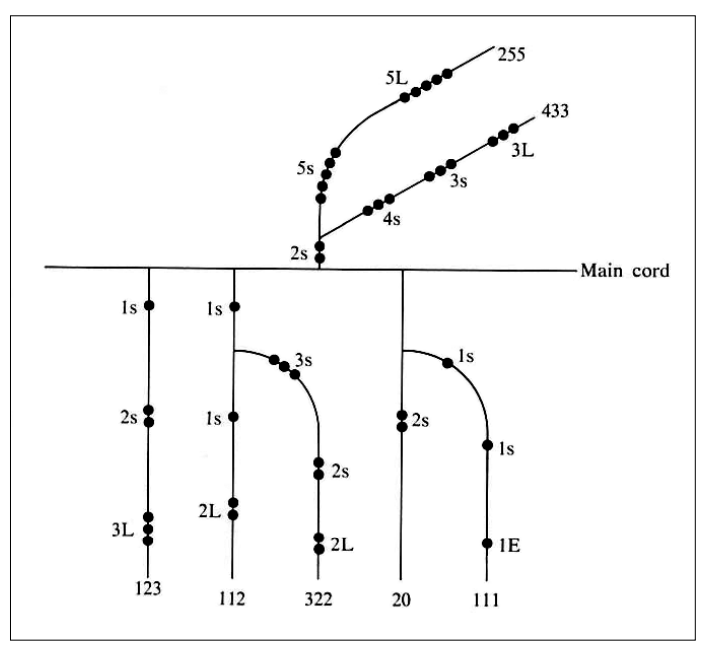

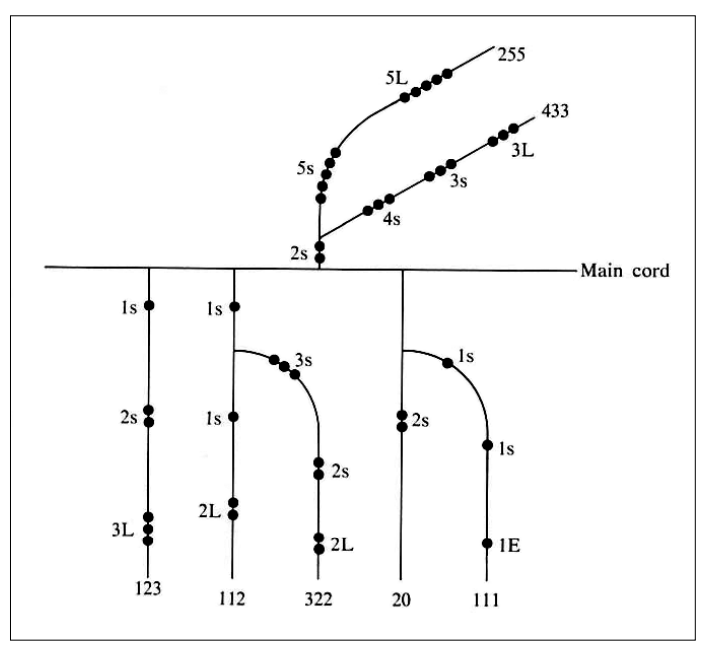

Figure 5: A khipu with arithmetical values. The topcord sums the values of pendants, and the topcord’s subsidiary those of the pendants’ subsidiaries (Ascher and Ascher 1997: 31, fig. 2.14). By permission of Marcia Ascher and Robert Ascher.

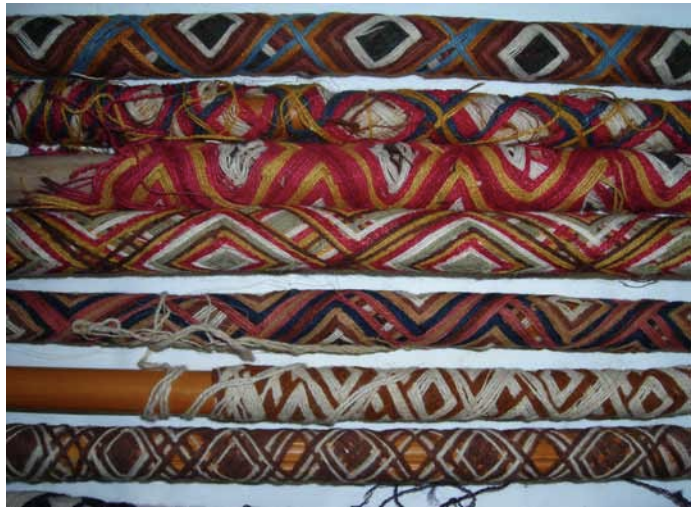

Figure 6: Paired khipu from Puruchuco: these two Inka-era specimens (UR 66–67) were rolled together, and bear similar color patterning. Photograph courtesy of Gary Urton.

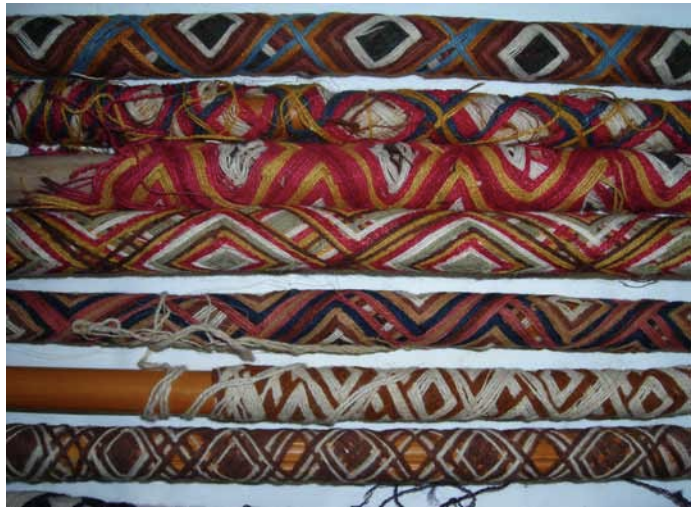

Figure 7: Khipus of Wari affiliation, several centuries earlier than Inka examples, bear information in the form of colored thread lashed around pendant cords. American Museum of Natural History T-223. Photograph courtesy of Carmen Arellano.

Figure 8: Wrapped sticks from funerary context at the Paracas site of Cerrillos. Photograph courtesy of Jeffrey Splitstoser

Figure 9: Wrapped sticks of late prehispanic and / or colonial dates in the collection of the Peabody Museum, Harvard. Photograph courtesy of William Conklin

Figure 10: Mummy from Chuquitanta with wrapped sticks. Photograph courtesy of Berndt Herrmann.

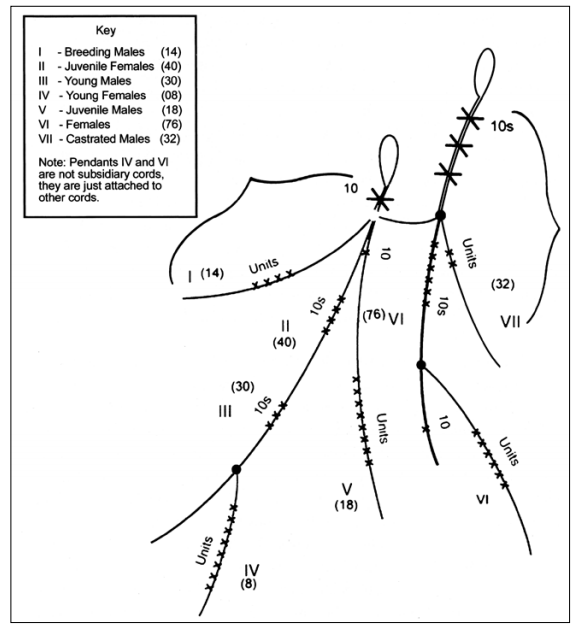

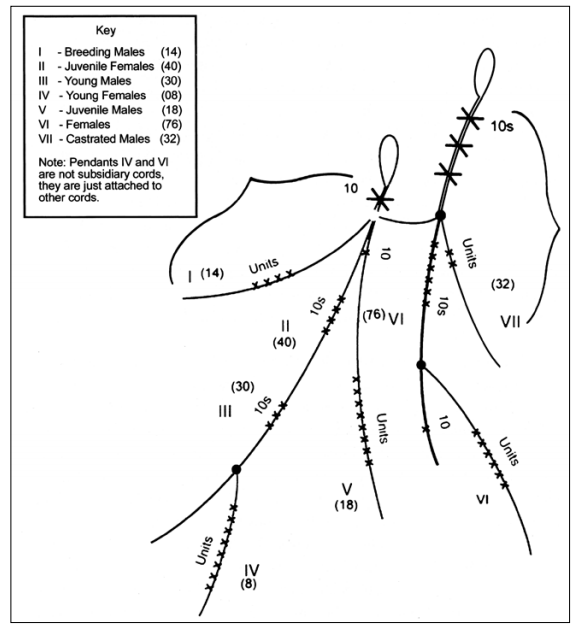

Figure 11: A herder’s khipu from modern Peru, studied by Carol Mackey in the late 1960s (in Quilter and Urton 2002: 334). It analyzes a herd of llamas by reproductive status.

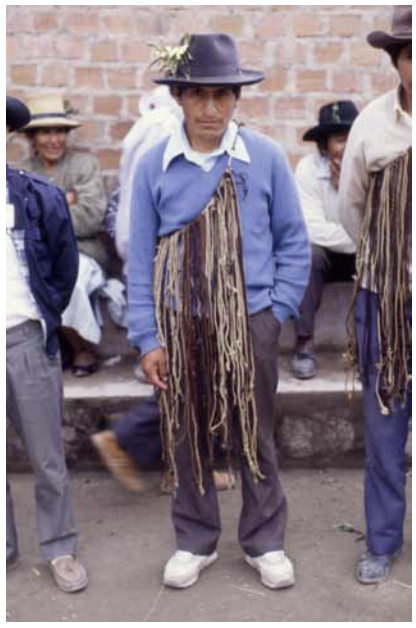

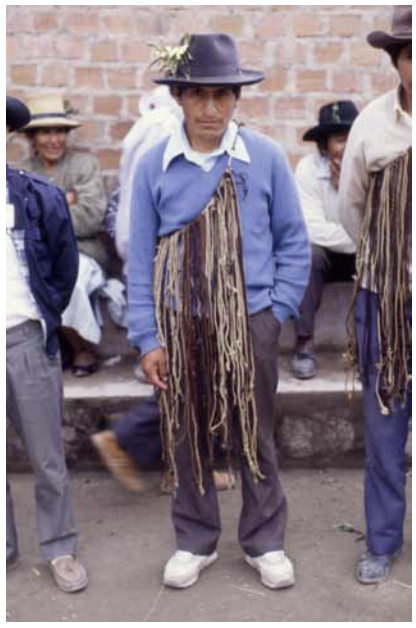

Figure 12: In Tupicocha, Peru, 1995, Celso Alberco assumed the presidency of his ayllu (a network of families) by donning its khipu. Author’s photograph.

Figure 13: A khipu belonging to ayllu Segunda Satafasca of Tupicocha. The overall design matches canonical Inka design. Author’s photograph.

Figure 14: Kaha Wayi, the house of ritual and traditional governance in Rapaz. It houses a large collection of vernacular khipus. Author’s photograph.

Figure 15: In 2004, Toribio Gallardo shows Rapaz’s khipu collection. Author’s photograph.

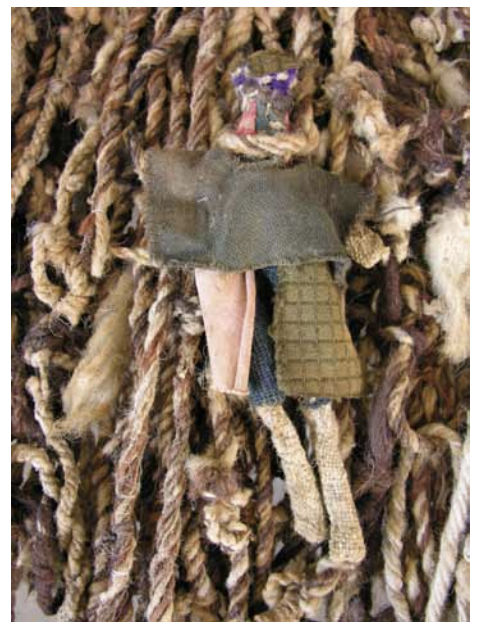

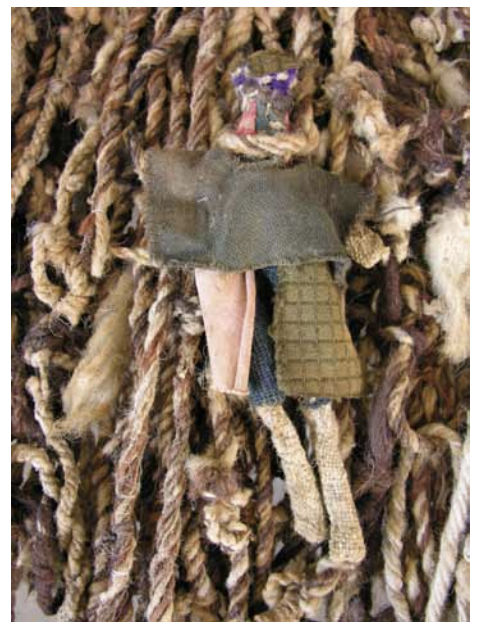

Figure 16: Some Rapaz khipus bear textile figurines. Author’s photograph.

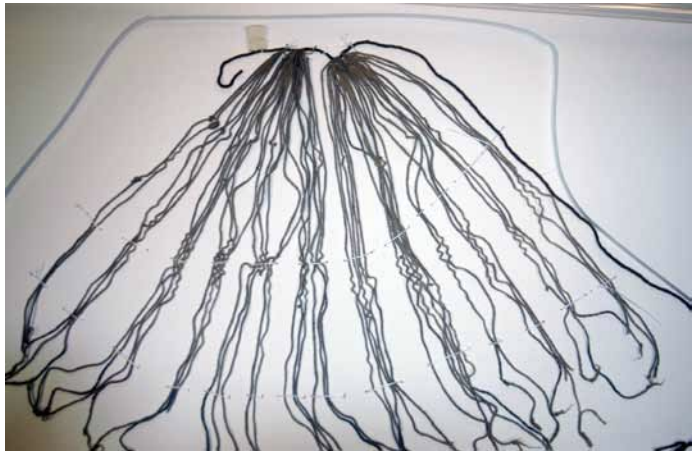

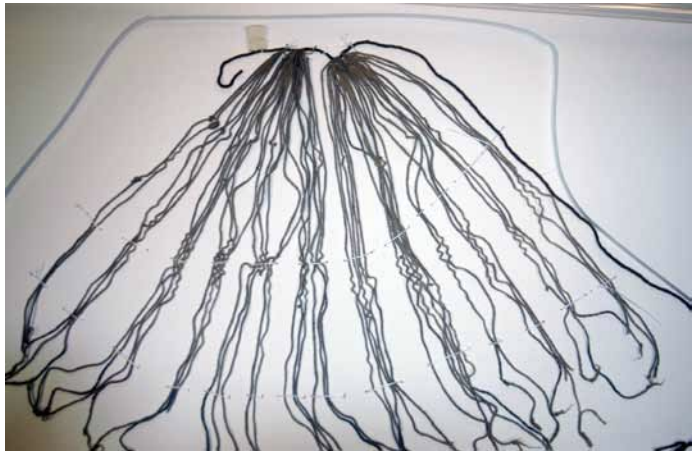

Figure 17: An Inka-era khipu with all its knots removed. Photograph courtesy of Gary Urton.

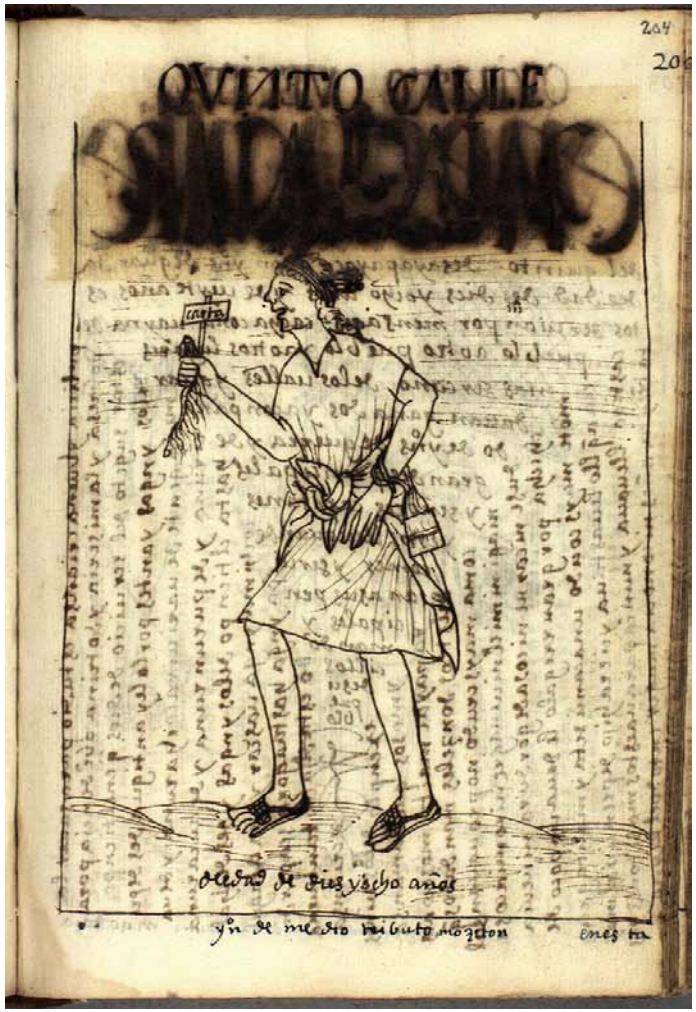

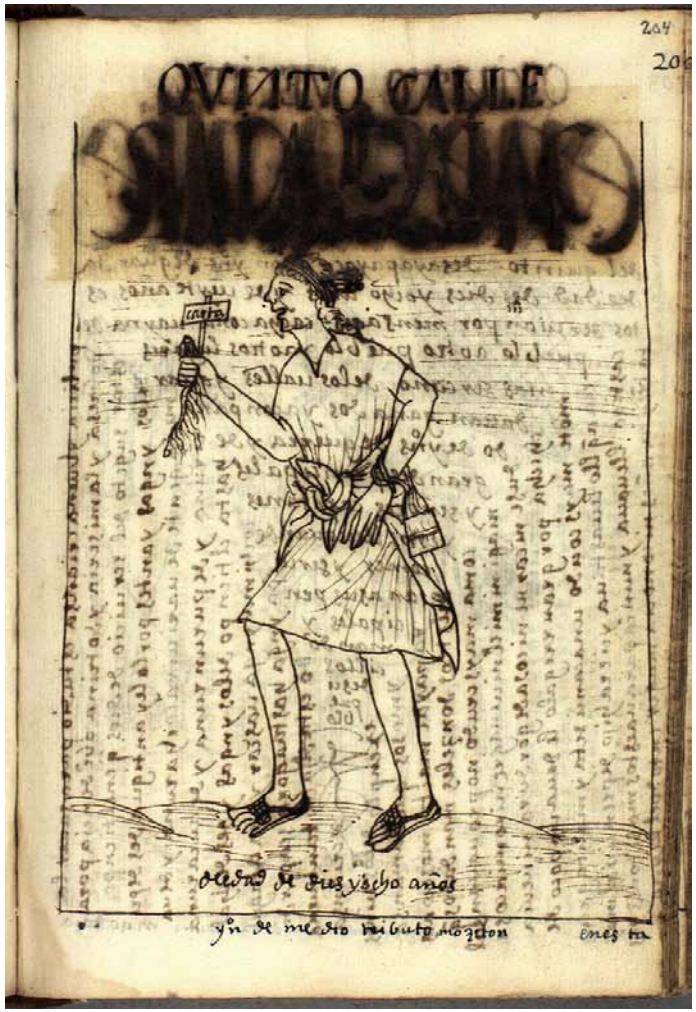

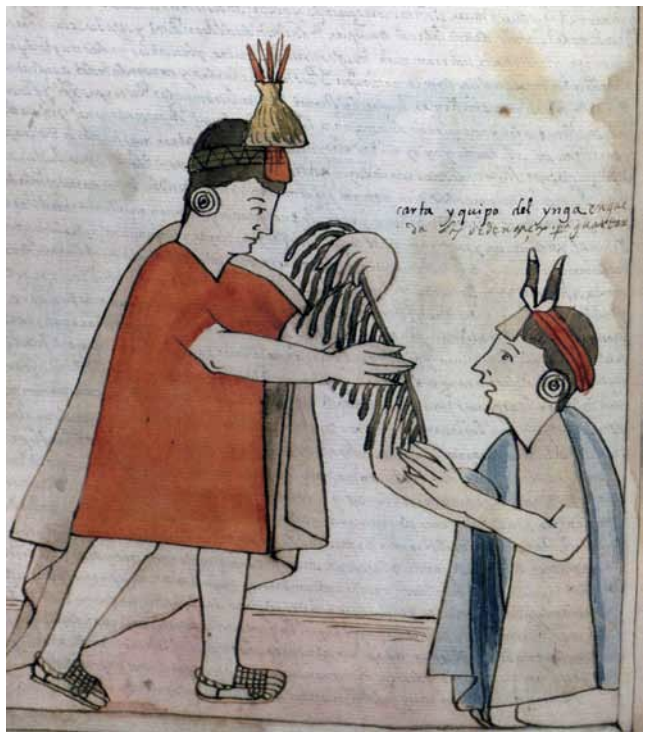

Figure 18: Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala drew this Inka postal runner with a khipu labeled “letter” (1980 [1615]: 178).

Figure 19: Inka khipu bound in fascicle for storage. Photograph courtesy of William Conklin.

Figure 20: Khipu(s) 41-2-6993 of the American Museum of Natural History are apparently marked as a pair by common attachment to a single end knob. Author’s photograph.

Figure 21: The Tupicochan practice of twisting an entire khipu into a single huge knot. Author’s photograph.

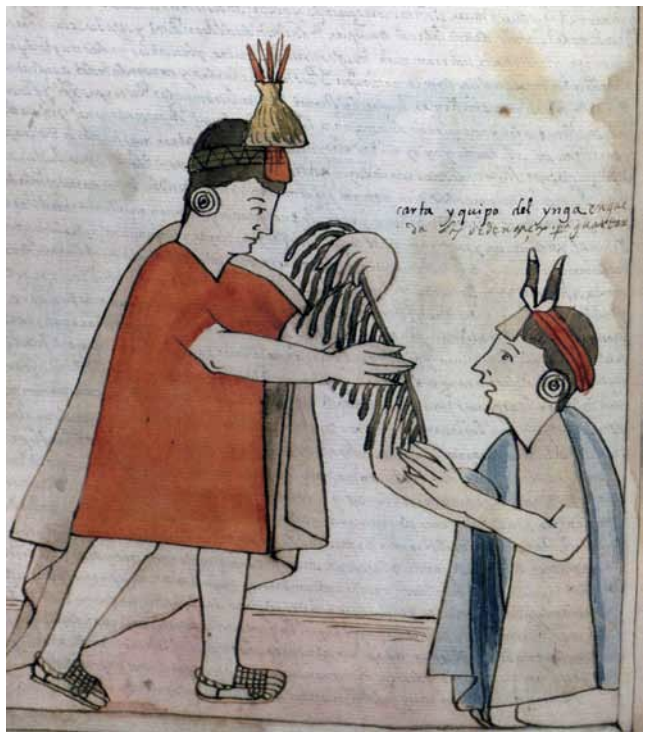

Figure 22: The 1590 de Murúa manuscript illustrates cooperative reading and finger-sorting of cords (de Murúa 2004: 124 verso).

Figure 23: At Laguna de los Cóndores, some Inka-era khipus found with enshrined mummies were tied to each other. Photograph courtesy of Gary Urton.

Figure 24: The Peabody Museum at Harvard holds a ring-shaped set of five conjoined khipus. Photograph courtesy of the Peabody Museum.