In a 3rd-century BCE Greco-Egyptian letter inscribed on papyrus, a man writes to his friend about a recent dream. He is writing in Greek, but in order to describe his dream accurately, he says, he must write the dream itself in Egyptian; after saying his Greek farewell, he recounts the dream and begins writing in a Demotic hand. This shift in languages entails a number of transitions: a new vocabulary, a wildly different grammar, but also one very important change — a change of script. In this chapter, I will explore the conceptual background between shifting from Greek to Demotic in this letter — not in linguistic or socio-political terms, but in terms of the actual practice of writing and the ideological trappings that accompany each writing-system. I will argue that the two scripts (not just the two languages) inform the letter-writer’s decision to choose and elevate Demotic as the proper vehicle for recounting his dream.

I will make this argument in three parts: first, by examining the different ways that these two languages were physically written; second, by ‘getting inside’ the process of writing an alphabetic (Greek) versus a logographic (Demotic) script; and third, by recreating the subjective experience of the alphabetic – logographic shift through comparative evidence (English and Chinese). Although I do not argue that there is something objectively more lofty or mystical in a logographic script, I do argue that when two cultures come into contact (Greek and Egyptian, English and Chinese) the opportunity is available to compare scripts and to create a hierarchy of uses for them.

This papyrus — a product of Greco-Egyptian cultural contact in 3rd-century Egypt — exhibits such a hierarchy in that these different scripts, Greek and Egyptian, appropriate their own registers and purposes. It is possible to see (after examining a) the materiality, b) the writing process and c) the subjective experience) an entire matrix of scriptorial ideology behind this language shift — an ideology which helps to explain why this Greco-Egyptian man, Ptolemaios, chooses Egyptian for his dream content. After all, he is making the transition from every-day affairs to the religious visions of the night, and as much as cultural and religious reasons might help to explain this shift, the actual, physical writing does as well. The difference between these two scripts is that of the mundane real world and that of the symbolic dream world — the Greek written, but the Egyptian drawn.

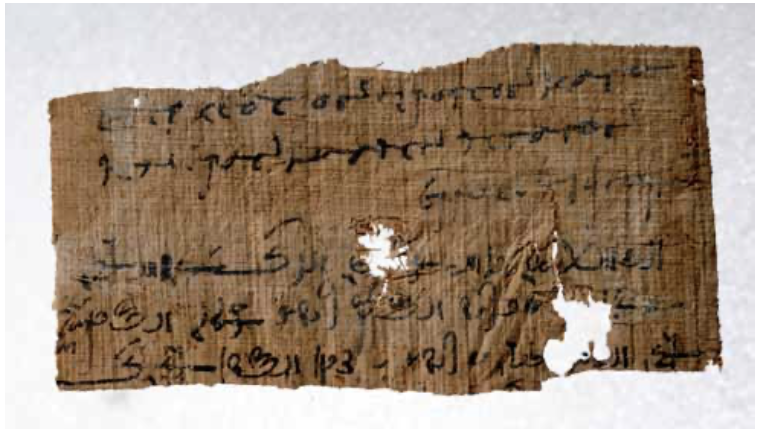

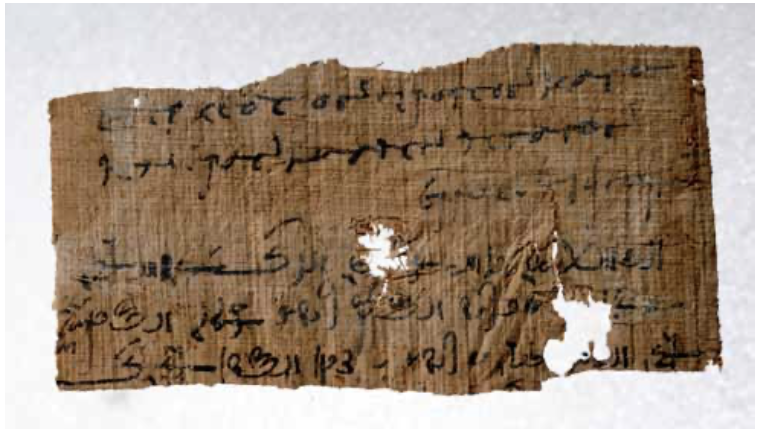

Figure 1: P.Cairo 30961 recto. Photograph Ahmed Amin, Egyptian Museum, Cairo.

Figure 2: Reed pen, Roman period, Karanis. KM 3820, Kelsey Museum of Archaeology, University of Michigan.

Figure 3: Rush pen inserted into holder built into palette. KM 1971.2.184 a–b, Kelsey Museum of Archaeology, University of Michigan.

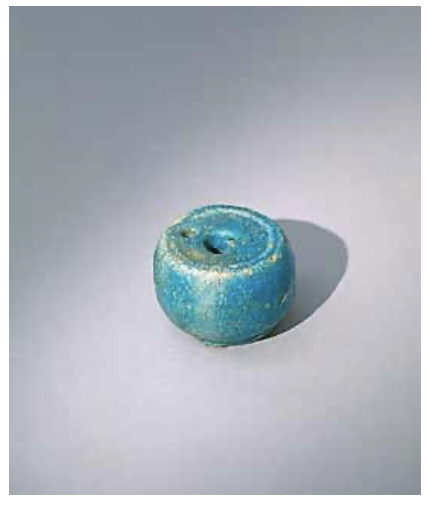

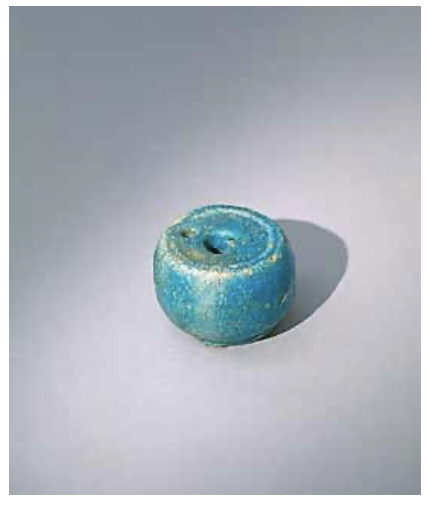

Figure 4: Faience inkwell, Ptolemaic-Roman period, Fayoum. KM 4969, Kelsey Museum of Archaeology, University of Michigan.

Figure 5: Wooden writing table, Karanis. KM 2.4802, Kelsey Museum of Archaeology, University of Michigan.

Figure 6: P.Cairo 30961 recto (detail): the ‘eye-determinative’ at the end of the Egyptian word for ‘dream’.