1.2: The Subdisciplines

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 66755

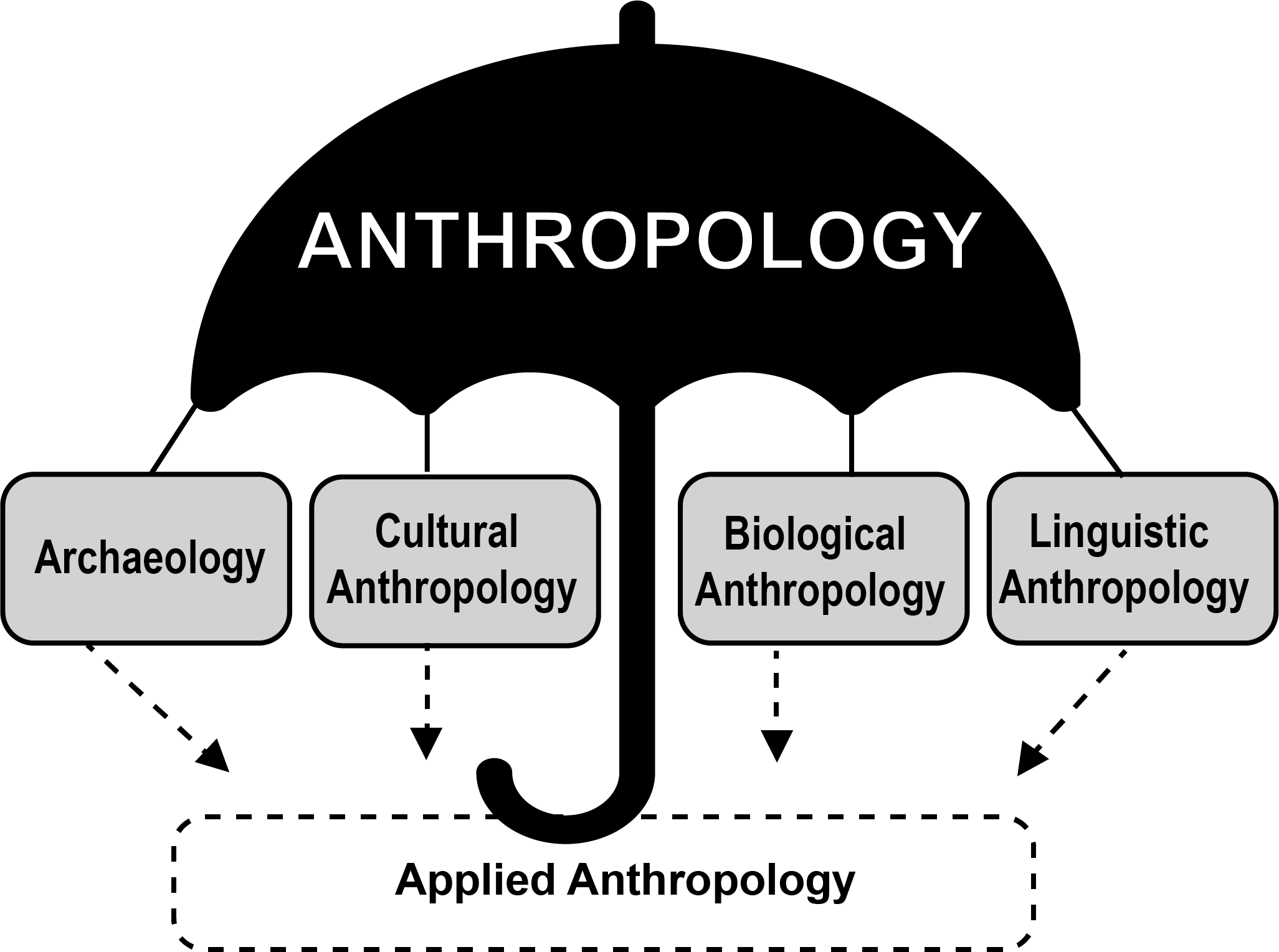

Because human experiences are varied and complex, we need a diversified tool kit to study them. Anthropology therefore comprises four subdisciplines: Some are more scientific (like biological anthropology), while others are more humanistic (like cultural anthropology). The scientific subdisciplines tend to use the scientific method to develop theories that explain human origins, evolution, material remains, or behaviors. The humanistic subdisciplines tend to use observational methods and interpretive approaches to understand human beliefs, languages, behaviors, cultures, and social organization. Findings from all four subdisciplines contribute to a multifaceted appreciation of human bio-cultural experiences, past and present.

Cultural Anthropology

Cultural anthropologists focus on similarities and differences among living societies. They suspend their own sense of what is “normal” in order to understand the perspectives of the people they study (cultural relativism). They learn these perspectives through participant-observation fieldwork: a method that involves living with, observing, and learning from the people one studies. Beyond describing another way of life, cultural anthropologists ask broader questions about humankind: Are human emotions universal or culturally specific? Does globalization make us all the same or do we maintain cultural differences? For cultural anthropologists, no aspect of human life is outside their purview: They study art, religion, healing, natural disasters, video gaming, even pet cemeteries. While many cultural anthropologists are intrigued by human diversity, they realize that people around the world share much in common.

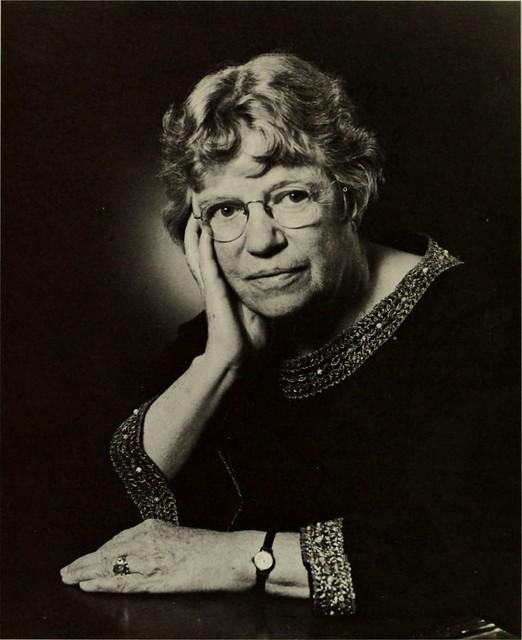

One famous American cultural anthropologist, Margaret Mead (1901–1978), conducted several cross-cultural studies of gender and socialization practices. In the early twentieth century in the United States, people wondered if the emotional turbulence of American adolescence was caused by the biology of puberty (and thus natural and universal) or something else. To find out, Mead set off for the Samoan Islands, where she lived for several months getting to know Samoan teenagers. She learned that Samoan adolescence was not angst-ridden (like it was in the United States), but rather a relatively tranquil and happy life stage. Upon returning to the United States, Mead wrote Coming of Age in Samoa, a best-selling book that was both sensational and scandalous (Mead 1928). In it, she critiqued U.S. parenting as overly restrictive, and contrasted it to Samoan parenting, which allowed teenagers to freely explore their community and even their sexuality. Ultimately, she argued that nurture (i.e., socialization) more than nature played a key role in the experience of child development.

Cultural anthropologists do not always travel far to provide insight into human experience. In the 1980s, American anthropologist Philippe Bourgois (1956–) wanted to understand how pockets of extreme poverty persist amid the wealth and overall high quality of life in the United States. To answer this question, he lived with Puerto Rican crack dealers in East Harlem, contextualizing their experiences both historically (in terms of socioeconomic dynamics in Puerto Rico and in the United States) and presently (in terms of social marginalization and institutional racism). Rather than blame crack dealers for their poor choices or blame our society for perpetuating inequality, he argued that both individual choices and social inequality can trap people in the overlapping worlds of drugs and poverty (Bourgois 2003).

Linguistic Anthropology

Language is a defining trait of human beings. While other animals have communication systems, only humans have complex, symbolic languages—more than 6,000 of them! Human language makes it possible to teach and learn, to plan and think abstractly, to coordinate our efforts, and to contemplate even our own demise. Linguistic anthropologists ask questions like: How did language first emerge? How has it evolved and diversified over time? How has language helped us succeed as a species? How does language indicate social identity? How does language influence our views of the world? If you speak two or more languages, you may experience how language affects you. For example, in English, we say: “I love you.” But Spanish speakers use different terms—“te amo,” “te adoro,” “te quiero,” and so on—to convey different kinds of love: romantic love, platonic love, maternal love, etc. The Spanish language arguably expresses more nuanced versions of love than the English language

One intriguing line of linguistic anthropological research focuses on the relationships between language, thought, and culture. It may seem intuitive that our thoughts come first; after all, we like to say, “Think before you speak.” However, according to the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis (also known as linguistic relativity), the language you speak allows you to think about some things and not other things. When Benjamin Whorf (1897–1941) studied the Hopi language, he not only found word-level differences, but also grammatical differences between Hopi and English tenses. He wrote that Hopi has no grammatical tenses to convey the passage of time. Rather, Hopi language only indicates whether or not something has “manifested.” Whorf argued that English grammatical tenses (past, present, future) inspire a linear sense of time, while Hopi language inspires a cyclical experience of time (Whorf 1956). Some critics, like German American linguist Ekkehart Malotki (1938–), refute Whorf’s theory, arguing that Hopi do have linguistic terms for time and that a linear sense of time is natural and perhaps universal. At the same time, Malotki recognized that English and Hopi tenses differ, albeit in ways less pronounced than Whorf proposed (Malotki 1983).

Other linguistic anthropologists track the emergence and diversification of languages, while others focus on language use in today’s social contexts. Still others explore how language is crucial to socialization: children learn their culture and social identities through language and nonverbal forms of communication (Ochs and Schieffelin 2012).

Archaeology

Archaeologists focus on the material past: the tools, food, pottery, art, shelters, seeds, and other objects left behind by people. Prehistoric archaeologists recover and analyze these materials to reconstruct the lifeways of past societies that lacked writing. They ask specific questions like: How did people in a particular area live? What did they eat? What happened to them? They ask general questions about humankind: When and why did humans first develop agriculture? How did cities first develop? What type of interactions did prehistoric people have with their neighbors?

One key method that archaeologists use to answer their questions is excavation—a method of careful digging and removing of dirt and stones to uncover material remains while recording their context. Archaeological research spans millions of years from human origins to the present. For example, Kathleen Kenyon (1906–1978), a British archaeologist, was one of few women working in this field in the 1940s. While excavating at Jericho (which dates back to 10,000 BCE), she discovered city structures and cemeteries built during the Early Bronze Age (3,200 yBP in Europe). Based on her findings, she argued that Jericho is the oldest city continuously occupied by different groups of people (Kenyon 1979).

Historical archaeologists study recent societies using material remains to complement the written record. For example, the Garbage Project, which began in the 1970s, is an archaeological project based in Tucson, Arizona. It involves excavating a contemporary landfill as if it were a conventional dig site. Archaeologists found a difference between what people say they throw out and what is actually in their trash. In fact, many landfills hold large amounts of paper products and construction debris (Rathje and Murphy 1992). This finding has practical implications for creating more environmentally sustainable waste-disposal practices.

Biological Anthropology

Biological anthropology, which will be thoroughly introduced later in this chapter, is the study of human origins, evolution, and variation. Some biological anthropologists focus on our closest living relatives: monkeys and apes. They examine the biological and behavioral similarities and differences between nonhuman primates and human primates (us!). Other biological anthropologists focus on extinct human species, asking questions like: What did our ancestors look like? What did they eat? When did they start to speak? And, how did they adapt to new environments?

Many biological anthropologists explore how human genetic and phenotypic (observable) traits vary in response to environmental conditions. For instance, Nina Jablonski (1953–) asks why darker skin pigmentation is more prevalent in high ultraviolet (UV) contexts (like Central Africa), while lighter skin pigmentation is more prevalent in low UV contexts (like Nordic countries). She explains this pattern in terms of the interplay among skin pigmentation, UV radiation, folic acid, and vitamin D. In brief, UV radiation breaks down folic acid, which is essential to DNA and cell production. Dark skin helps to block UV, thereby protecting the body’s folic acid reserves in high-UV contexts. Light skin evolved when humans migrated out of Africa to low-UV contexts, where dark skin blocks too much UV radiation, compromising the body’s ability to absorb vitamin D from the sun (vitamin D is essential to calcium absorption and a healthy skeleton). Jablonski shows that the spectrum of skin pigmentation that we see today evolved to balance UV exposure with the bodily need for vitamin D and folic acid (Jablonski 2012).

While some biological anthropologists study hominins (modern-day humans and human ancestors), others focus on nonhuman primates. For example, Jane Goodall (1934–) has devoted her life to studying wild chimpanzees (Goodall 1996). Beginning in the 1960s when she began her research in Tanzania, Goodall challenged widely held assumptions about the inherent differences between humans and apes. At the time, it was assumed that monkeys and apes lacked the social and emotional traits that made human beings such exceptional creatures. However, Goodall discovered that, like humans, chimpanzees also make tools, socialize their young, have intense emotional lives, and form strong maternal-infant bonds. Her work highlights the value of field-based research in natural settings as it can reveal the complex lives of nonhuman primates. Throughout this book, we will learn about many examples of biological anthropological research that explores our earliest ancestors, our evolution, and our nonhuman primate cousins.

Applied Anthropology

Sometimes considered a fifth subdiscipline, applied anthropology involves the practical application of anthropological theories, methods, and findings to solve real-world problems. Applied anthropologists are employed outside of academic settings, in both the public and private sectors, including business or consulting firms, advertising companies, city government, law enforcement, the medical field, nongovernmental organizations, and even the military.

Applied anthropologists span the subdisciplines. An applied archaeologist might work in cultural resource management to assess a potentially significant archaeological site unearthed during a construction project. An applied cultural anthropologist could work for a technology company that seeks to understand the human-technology interface in order to design better tools.

Medical anthropology is an example of both an applied and theoretical area of study that draws on all four subdisciplines to understand the interrelationship of health, illness, and culture. Rather than assume that disease resides only within the individual body, medical anthropologists explore the environmental, social, and cultural conditions that impact the experience of illness. For example, in some cultures, people believe that illness is caused by an imbalance within the community. Therefore, a communal response, such as a group healing ceremony, is necessary to restore the health of the person and the group. In other cultures, like mainstream U.S. society, people typically go to a doctor to find the biological cause of an illness and then take medicine to restore the individual body.

Trained as both a physician and medical anthropologist, Paul Farmer (1959– ) demonstrates the potential of applied anthropology. During his college years in North Carolina, Farmer’s interest in the Haitian migrants working on nearby farms inspired him to visit Haiti. There, he was struck by the poor living conditions and lack of health care facilities. Eventually, as a physician, he would return to Haiti to treat diseases, like tuberculosis and cholera, that were rarely seen in the United States. As an anthropologist, he would contextualize the suffering of his Haitian patients in relation to the historical, social, and political forces that impact Haiti, the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere (Farmer 2006). Today, he not only writes academic books about human suffering, he also takes action. Through the work of Partners in Health, a nonprofit organization that he cofounded, he has opened health clinics in many resource-poor countries and trained local staff to administer care. In this way, he applies his medical and anthropological training to improve people’s lives.