1.3: What is Biological Anthropology

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 66756

The focus of this book is the anthropological subdiscipline of biological anthropology, which is the study of the human species from a biological perspective. Biological anthropology uses a scientific and evolutionary approach to answer many of the same questions all anthropologists are concerned with: What does it mean to be human? Where do we come from? Who are we today? Biological anthropologists are concerned with exploring how humans vary biologically, how humans adapt to their changing environments, and how humans have evolved over time and continue to evolve today. Some biological anthropologists also study nonhuman primates to learn about what we have in common and how we differ.

.jpg?revision=1)

You may have heard biological anthropology referred to by another name—physical anthropology. Physical anthropology is an area of research that dates to as far back as the eighteenth century, when it focused mostly on physical variation among humans. Some early physical anthropologists were also physicians interested in comparing and contrasting human skeletons. These researchers dedicated themselves to measuring bodies and skulls (anthropometry and craniometry) in great detail. Many also acted under the misguided and oftentimes racist belief that human biological races existed and it was possible to differentiate between, or even rank, such races by measuring differences in human anatomy. Most anthropologists today agree that there are no biological human races and that all humans alive today are members of the same species and subspecies, Homo sapiens sapiens. We recognize that the differences we can see between peoples’ bodies are due to a wide variety of factors, including our environment, our diet, the activities we engage in, and our genetic makeup.

The subdiscipline has changed a great deal since these early years. Biological anthropologists no longer set out to identify human differences in order to assign people to groups, like races. The focus is instead understanding how and why human and primate variation developed through evolutionary processes. The name for the subdiscipline has transitioned in recent years to reflect these changes. Many believe the term biological anthropology better reflects the subdiscipline’s focus today, which includes genetic and molecular research. Nevertheless, the term physical anthropology is still common.

The Scope of Biological Anthropology

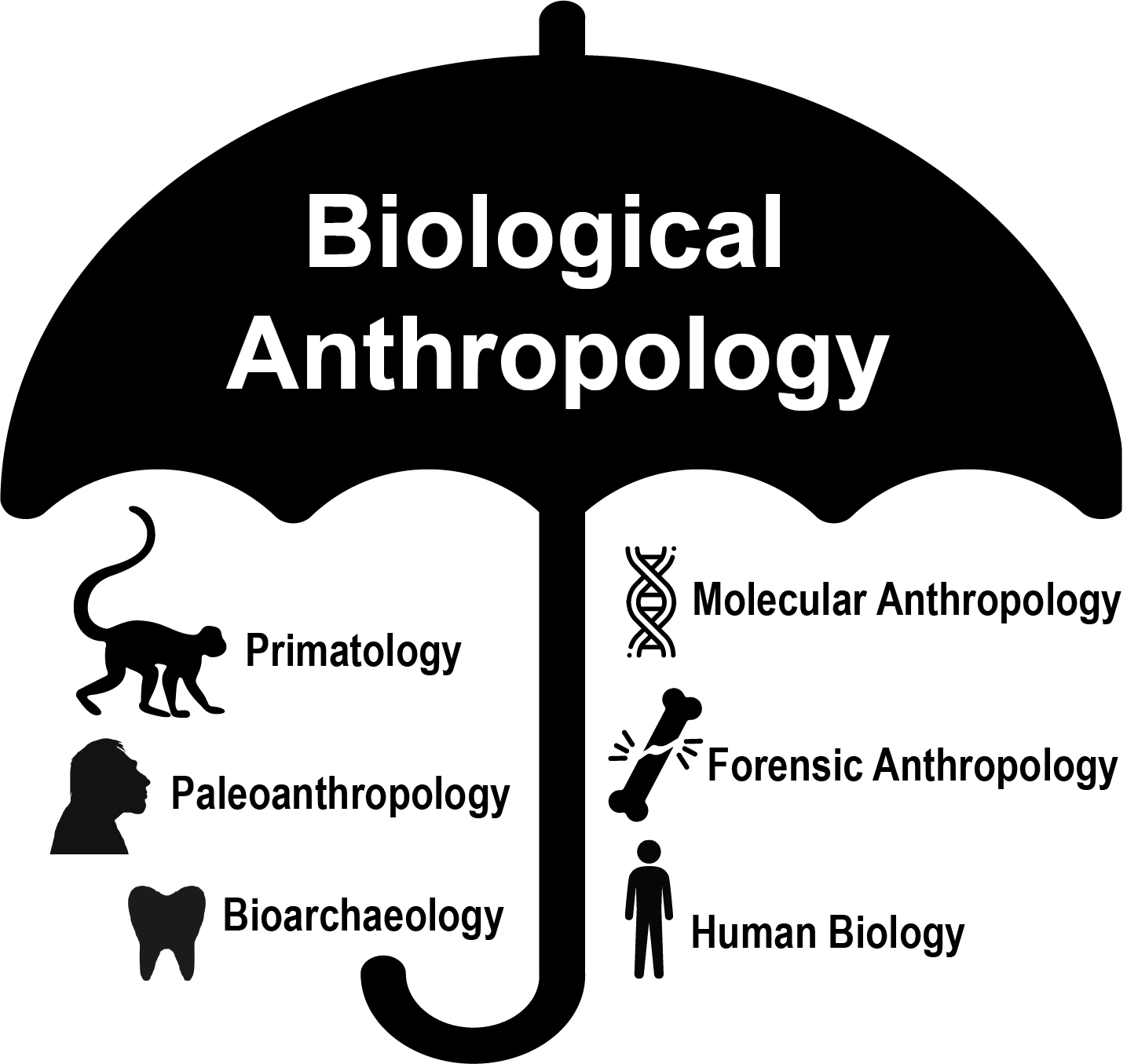

Just as anthropology as a discipline is wide ranging and holistic, so too is the subdiscipline of biological anthropology. There are at least six subfields within biological anthropology. Each subfield focuses on a different dimension of what it means to be human from a biological perspective. Through their varied research in these subfields, biological anthropologists try to answer the following key questions:

- What is our place in nature? How are we related to other organisms? What makes us unique?

- What are our origins? What influenced our evolution?

- How and when did we move/migrate across the globe?

- How are humans around the world today different from and similar to each other? What influences these patterns of variation? What are the patterns of our recent evolution and how do we continue to evolve?

The terms subfield and subdiscipline are very similar and can be confusing because they are often used interchangeably. In this book we use subdiscipline to refer to the four major areas of focus that make up the discipline of anthropology: biological anthropology, cultural anthropology, archaeological anthropology, and linguistic anthropology. When we use the term subfield we are referring to the different specializations within biological anthropology. These subfields include primatology, paleoanthropology, molecular anthropology, bioarchaeology, forensic anthropology, and human biology.

Primatology

Primatologists study the anatomy, behavior, ecology and genetics of living and extinct nonhuman primates, including apes, monkeys, tarsiers, lemurs, and lorises, because nonhuman primates are our closest living biological relatives. The research done by primatologists gives us insights into how evolution has shaped our species and primates in general. Through such studies we have learned that all primates share a suite of traits. Primates, for instance, have nails instead of claws, have hands that can grasp and manipulate objects, invest great amounts of time and energy in raising just a few offspring, and have complex social behaviors.

Similar to Jane Goodall’s studies of wild chimpanzees, Dian Fossey’s research among mountain gorillas provided scientists with some illuminating insights into our primate cousins. She learned, for instance, that gorillas are like humans in that they have families and form strong maternal-infant relationships. Gorillas mourn the death of their group members, and also exhibit behaviors similar to humans such as playing and tickling. Importantly, the work of Dian Fossey, Jane Goodall, Karen B. Strier (see Appendix B), and others focus on primate conservation: They have brought attention to the fact that 60% of primates are currently threatened with extinction (Estrada et al. 2017).

Paleoanthropology

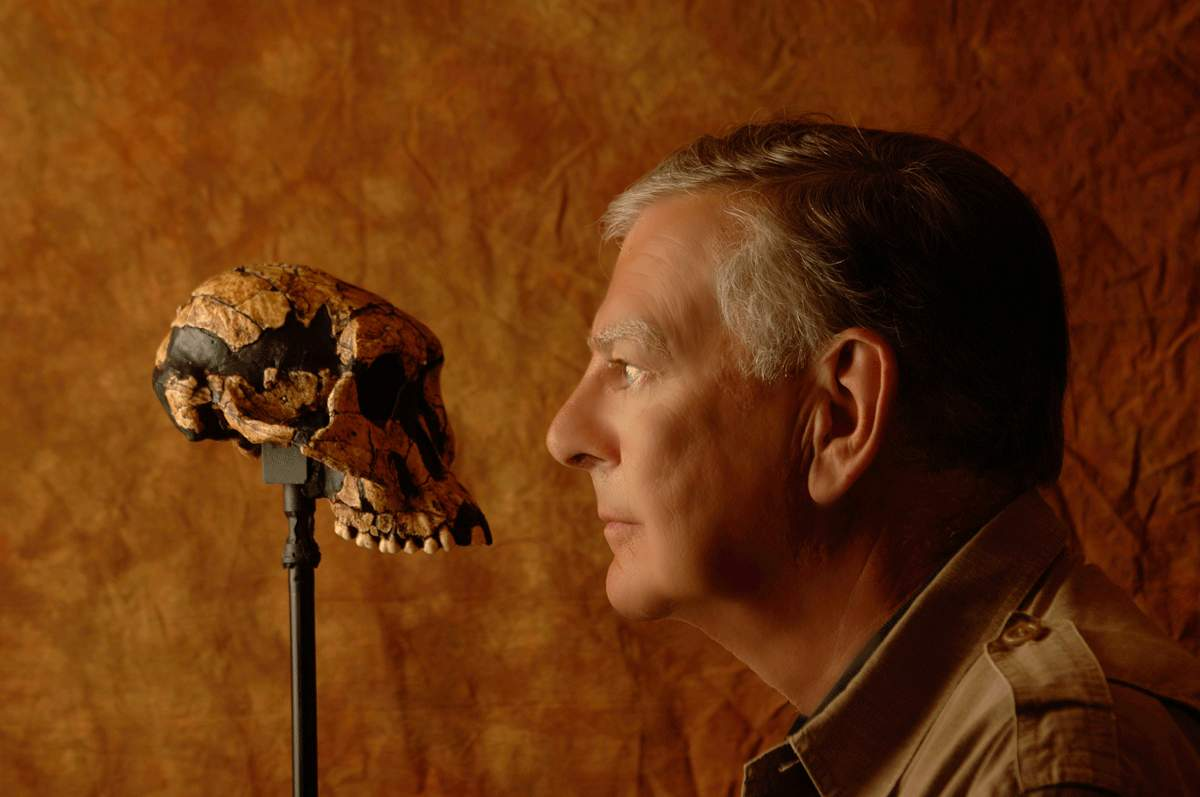

Paleoanthropologists study human ancestors from the distant past to learn how, why, and where they evolved. Because these ancestors lived before there were written records, paleoanthropologists have to rely on various types of physical evidence to come to their conclusions. This evidence includes fossilized remains (particularly fossilized bones), artifacts such as stone tools, and the contexts in which these items are found. Paleoanthropologists have made some monumental discoveries that have shaped the way we understand hominin evolution (hominin refers to humans and fossil relatives that are more similar to us than chimpanzees).

One such discovery was made in Ethiopia in 1974 by paleoanthropologist Donald C. Johanson. He found the remains of a 3.2-million-year-old fossilized skeleton he named Lucy (she was named after the Beatles song “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,” which the archaeologists played repeatedly at the celebration the evening after her discovery). Lucy was a remarkable find because she represented a new hominin species, Australopithecus afarensis, and the skeleton was over 40% complete. Like humans, she was bipedal (walked on two legs) and likely used tools. However she had a much smaller brain than humans, larger teeth and likely spent time in trees and on the ground. She was, in many ways, a transitional species between humans and earlier primates.

Since the discovery of Lucy, several hundred more Australopithicus fossils have been found in Africa, as you will learn more about in chapter nine. From these finds, we know that many Australopithicus species flourished for millions of years. Some of these species likely led to our genus (Homo), while others appear to have died off. These findings helped us learn that human evolution did not occur in a simple, straight line, but branched out in many directions. Most branches were evolutionary “dead ends.” Humans are now the only hominins left living on planet Earth. Paleoanthropologists frequently work together with other scientists such as archaeologists, geologists, and paleontologists to interpret and understand the evidence they find. Paleoanthropology is a dynamic subfield of biological anthropology that contributes significantly to our understanding of human origins and evolution.

Molecular Anthropology

Molecular anthropologists use molecular techniques (primarily genetics) to compare ancient and modern populations and to study living populations of humans and nonhuman primates. By examining DNA sequences in different populations, molecular anthropologists can estimate how closely related two populations are, as well as identify population events, like a population decline, that explain the observed genetic patterns. This information helps scientists trace patterns of migration or identify how people have adapted to different environments over time.

Some exciting work that molecular anthropologists are doing today is studying the genetic material they find in ancient specimens. From this work we have learned, for instance, that many people in the world today have inherited some DNA from Neanderthals and/or a newly discovered species known as Denisovans. This tells us that at some point in our ancient past our modern human ancestors mated with Neanderthals and Denisovans and their genes were passed down to us. Moreover, it is now believed some of these genes helped our human ancestors survive.

From the work of molecular anthropologists we have also learned which genes distinguish us genetically from our closest living relatives: chimpanzees, bonobos, and gorillas. In the case of chimpanzees, our genomes are somewhere between 96% and 99% identical (Prufer et al. 2012; Relethford and Bolnick 2018). Yet that 2-4% contributes to a lot of physical (morphological) and behavioral differences! Molecular anthropology is a field changing quickly as new techniques and discoveries shape our understanding of ourselves and our nonhuman primate cousins.

Bioarchaeology

Bioarchaeologists study human skeletal remains and the soils and other materials found in and around the remains. They use the research methods of skeletal biology, mortuary studies, osteology, and archaeology to answer questions about the lives and lifeways of past populations. Through studying the bones and burials of past peoples, bioarchaeologists search for answers to how people lived and died. For example, bioarchaeologists can estimate the sex, height, and age at which someone died. They can also gather clues about their lifestyle based on the skeleton, since bones respond to muscle use and developed muscle attachments may indicate extensive muscle use. Most bioarchaeologists study not just individuals, but populations, to reveal biological and cultural patterns.

Bioarchaeologists are also interested in learning about ancient people’s health and nutrition, the diseases they suffered from and injuries they suffered. They may also look for clues to what people ate by examining the wear and condition of teeth or, in the case of well-preserved specimens, the residue from their last meals. Chemical studies of bones and teeth can also provide information about people’s diets as well as where people lived and moved during their lives. Bioarchaeologists can reconstruct human migration and track the growth or decline of populations by looking for patterns of malnutrition, disease, and activities.

Not all places are ideal for finding well-preserved human remains. Environments that are very cold, very dry, or devoid of oxygen can preserve corpses for many years, sometimes centuries. In 1991, a group of hikers found the body of a man frozen in the Italian Alps. Because of how well-preserved the body was, the discoverers initially thought he might be a hiker who had died several years prior. However, once bioarchaeologists had a chance to study the body, they discovered the man had died around 5,300 years ago! Nicknamed Őtzi, or the Iceman, bioarchaeologists determined he was wearing leggings, a coat, and shoes made of leather and fur when he died. They also discovered he had an arrow embedded in his left shoulder, suffered from osteoporosis, had multiple tattoo patterns throughout his body and was infected by the bacterium H. pylori, a common human stomach pathogen that likely gave him significant stomach pain. Researchers later found similarities between the strain of H. plyori bacterium that plagued Őtzi and the strains seen today in parts of Central and Southern Asia. Modern-day Europeans have strains of the bacterium that reflect mixtures of both African and Asian strains. This research helped scientists demonstrate that for thousands of years after Őtzi died human groups were migrating all over the world, even returning to Africa and then moving back north again. Research within the subfield of bioarchaeology is continually providing important insights into humanity’s past.

Forensic Anthropology

Forensic anthropologists use many of the same techniques as bioarchaeologists to develop a biological profile for unidentified individuals including estimating sex, age at death, height, ancestry, diseases they had, or other unique identifying features. They may also go to a crime or accident scene to assist in the search and recovery of human remains, and/or identify trauma, like fractures, on bones. The popular television program Bones told the fictional story of a forensic anthropologist, Dr. Temperance Brennan, who brilliantly interpreted clues from victims’ bones and helped solve crimes. While the show includes forensic anthropology techniques and responsibilities, it also includes many inaccuracies. For example, forensic anthropologists generally do not collect trace evidence like hair or fibers, run DNA tests, carry weapons, or solve criminal cases. These researchers play an important role in aiding law enforcement to identify human remains.

Some forensic anthropologists have been called on to interpret the remains of victims of mass murders, such as the case of the town of El Mozote in El Salvador. In December of 1981, during the country’s intense civil war, over 1,000 people were brutally killed by the Salvadoran right-wing military in and around a church in the town of El Mozote. Researchers later discovered that the U.S. government, under President Reagan, funded and trained the Special Forces of the Salvadoran Army who perpetrated the massacre. Starting in the mid-1990s, human rights organizations began to investigate the incident as a war crime, and finally, in 2015, a team of forensic anthropologists were called upon to study the bones of the deceased and try to reconstruct what happened at El Mozote and how the victims died (Binford 2016). Their work provided important clues that helped bring some closure to the families and survivors of this horrible incident. It also provided answers to investigators looking to bring accountability to those responsible.

Forensic anthropology is considered an “applied” area of biological anthropology, since it is a practical application of anthropological theories, methods, and findings to solve real-world problems. While many forensic anthropologists are also academics and work for colleges and universities, some are employed by other agencies. Forensic anthropology is an active area of applied biological anthropology and a career that is useful all over the world.

Human Biology

Many biological anthropologists do work that falls under the label human biology. This type of research is varied, but tends to explore how the human body is impacted by different physical environments, cultural influences, and nutrition. These include studies of human variation or the physiological differences among humans around the world. For instance, some humans have the ability to digest lactase in milk into adulthood, and others lack this ability. Some humans have an enhanced ability to resist malarial infections. Some humans tend to be very tall and lean while others are short and stocky. Still others tend to have dark skin and others lighter brown and even pale skin colors.

Some of these anthropologists study human adaptations to extreme environments, which includes individual physiological responses and genetic advantages populations develop to help them live there. For example, people born at very high elevations adapt to life in an environment with decreased oxygen. Research has shown that populations that have lived for many generations at very high elevations, such as those in parts of Tibet, Peru, and Ethiopia, have developed long-term physiological adaptations. These include large lungs and chests and enhanced oxygen respiration and blood circulation systems that help them survive in an environment that otherwise might cause life-threatening hypoxia (oxygen deprivation) (Bigham 2016). Some anthropologists believe Tibetans’ adaptation to living in high altitudes, estimated to have occurred in less than 3,000 years, is one of the fastest cases of human evolution in the scientific record!

In addition to studying how humans adapt to their physical environments and vary biologically, some biological anthropologists are interested in how nutrition and disease affect human growth and development. The modern Western diet that is high in processed starches, refined carbohydrates, saturated fats, sugar, and salt is increasingly causing a number of metabolic conditions. As cultural groups around the world begin to replace their traditional diets with these processed food products, they begin to experience a rise in diseases that plague Western societies, such as diabetes, heart disease, and hormonal imbalances. Other biological anthropologists have asked why girls in Western societies have begun to menstruate earlier (sometimes as young as seven years of age). A definitive explanation is still unresolved. Some speculate this may have to do with changes in our diet, while others believe it may also have to do with exposure to chemicals in the environment or other factors. Biological anthropologists engage in a wide range of research that span the breadth of human biological diversity.

The six subfields of biological anthropology—primatology, paleoanthropology, bioarchaeology, molecular anthropology, forensic anthropology, and human biology—all help us understand what it means to be biologically human. From molecular analyses of our cells, to studies of our changing skeleton, to research on our nonhuman primate cousins, biological anthropology helps answer the central question of the larger discipline of anthropology: What does it mean to be human? Despite their different foci, all biological anthropologists share a commitment to using a scientific approach to study how we became the complex, adaptable species we are today.