Primate Classification

Format: In person or online

Side and top views of postorbital closures and bars.

Author: Beth Shook

Modified from labs by Henry M. McHenry, University of California, Davis

Time needed: 50-60 minutes

Supplies Needed

- Primate and non-primate skeletons and skulls. These can be real, casts, or images. A list is provided below.

- Labels for the skeletons and skulls (e.g., Primate or Strepsirrhine)

- Resources for students to look up specific examples of Platyrrhines (e.g., Rowe. 1996. The Pictorial Guide to Living Primates)

- Student worksheet (attached)

Readings

- Etting, Stephanie. 2019. Chapter 5: Meet the Living Primates. Explorations.

Introduction

People belong to the zoological order Primates, which is one of the many orders within the class Mammalia. This lab gives students the opportunity to observe characteristics of the skeleton that differentiates primates from other mammals and compare primates to one another.

Before beginning, students should consider the following conceptual questions: What can bones tell us about the animal to which they belonged? Specifically, what might the skeleton tell us about:

- what the animal ate?

- its mode of locomotion?

- the environment it lived in?

- its behavior?

Bones can reflect the lifestyle of primates, and the characteristics they share are likely reflective of early primate ancestors. For example, most primates move about in trees by grasping with their feet and hands. Primatologists believe the common ancestor of all living primates was an arboreal climber with prehensile extremities who relied on vision more than olfaction (smell). This ancestor may have had some depth perception, made possible by the overlapping visual fields of forward-facing eyes, and hands with the ability to manipulate objects. Thus, physical traits that help us distinguish primates from other mammals include:

- a generalized skeletal structure for arboreal life;

- convergent eyes (forward facing);

- eye orbits with a postorbital bar or plate;

- reduced snout length (related to less reliance on smell);

- opposable thumbs and big toes;

- flattened nails instead of, or in addition to, claws;

- a larger brain size;

- differences in tooth morphology (reflects variable diets);

- and prehensile (grasping) hands and feet.

Steps

- Before beginning this lab, the instructor should select skeletal materials, casts, or images of skeletal materials for students, and arrange them at various stations. All skeletal materials should be labeled with cards/small labels with terms that match the student worksheets (e.g., Primate, Strepsirrhine). Alternatively, virtual images can be

- linked to the student worksheet to create a virtual lab. Materials include non-primate, nonhuman primate, and primate skulls and articulated skeletons. Specifically:

- Station 1: (a) primate (e.g., monkey) articulated skeleton, and (b) non-primate (e.g., cat or dog) articulated skeleton. Preservation should be good enough to see nails/claws.

- Station 2: (a) non-primate (cow or pig) skull with teeth, (b) dog skull with teeth, (c) monkey skull with teeth, and (d) human skull with teeth. Be sure that the surfaces of the teeth are visible in addition to the eye orbits (e.g., the mandible can be separated from the skull or there are multiple images to depict various views).

- Station 3: (a) strepsirrhine (e.g., lemur) and (b) haplorrhine (e.g., monkey).

- Station 4: (a) tarsier. Because this station asks students whether the tarsier is more like a strepsirrhine or haplorrhine for given traits, they should have either completed Station 3 or have access to comparative materials at this station too. Additionally, because tarsiers are small, it can be difficult for students to clearly identify some of the traits, and it can be useful to also provide a diagram with a closer view.

- Station 5: (a) New World monkey skull and (b) catarrhine skull (preferably an Old World monkey). Be sure to use adult primate skulls so that students can accurately compare their dental formulas. Additionally, this station requires photographs of these primates so that students can compare nose shapes and look up examples of different types of New World monkeys.

- Station 6: (a) Old World monkey articulated skeleton, (b) ape articulated skeleton, and (c) human articulated skeleton. This station also asks students to compare molar cusp patterns, so it can be useful to also have separate skulls or photos of dentition.

- Station 7: No skeletal materials are required. However, students should have completed Stations 3 through 6.

- The instructor should choose to assign this lab as an individual or small group activity.

- An introduction to encourage students to think about “form and function” of the skeleton would be helpful. Additionally, students should be encouraged to think broadly (incorporating what they already know about animals, what they eat, and how they move), especially when answering questions at Stations 1 and 2. Instructors should be sure students are familiar with the traits in the lab (e.g., foramen magnum, tooth comb, Y5 or bilophodont molar cusp patterns) or are given resources to identify these traits at the various stations.

- The lab consists of seven “stations.” Stations 1 and 2 focus on “form” and “function” of the skeleton, while stations 3 through 6 focus on the organization of the primate taxonomy. Students will rotate through stations filling out tables and answering questions on their worksheets. Instructors may assign some or all stations. Stations can be

- completed in any order, however Station 7 requires the completion of stations 3 through 6 first.

- Station 1: Students compare primate and non-primate postcrania and relate the form of the skeletons to their function.

- Station 2: Students compare primate and non-primate teeth and crania and relate the form of the skeletons to their function.

- Station 3: Students compare strepsirrhines and haplorrhines.

- Station 4: Students identify tarsier traits and evaluate their classification.

- Station 5: Students compare New World monkeys to catarrhines.

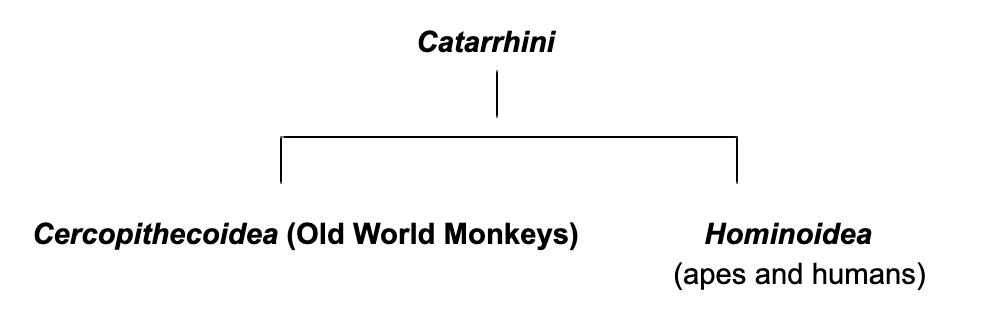

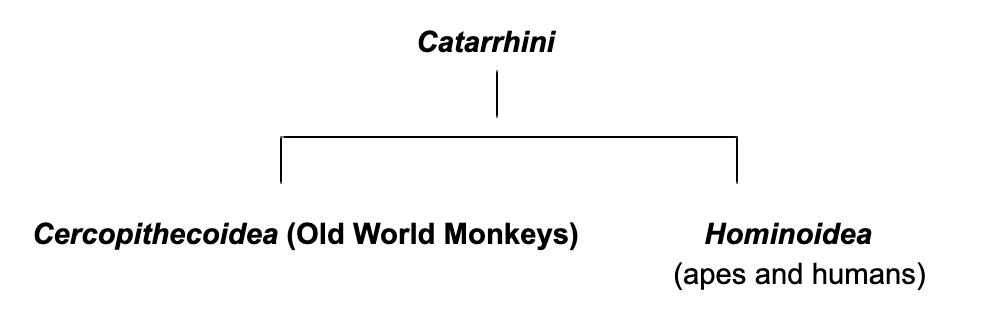

- Station 6: Students compare a cercopithecoid to two hominoids (an ape and human).

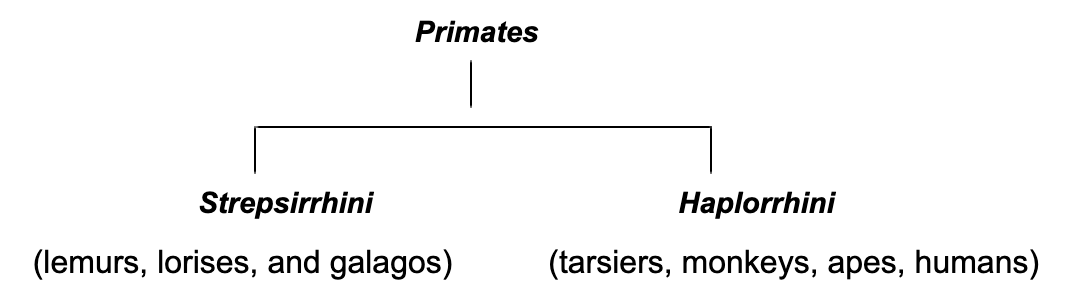

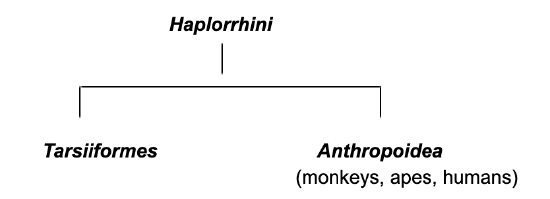

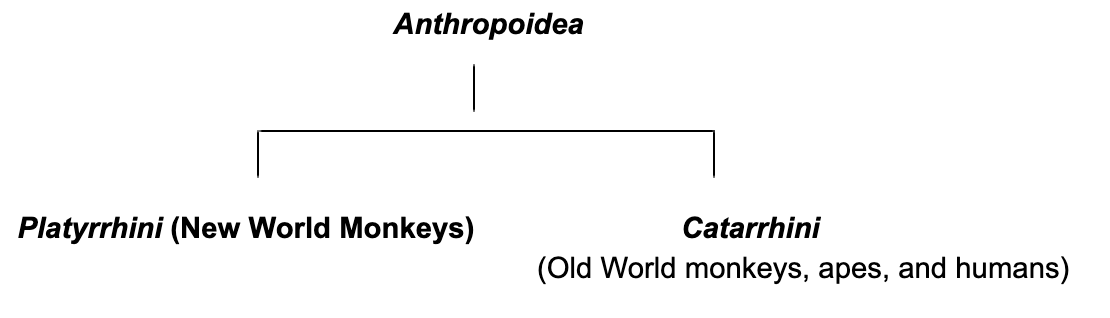

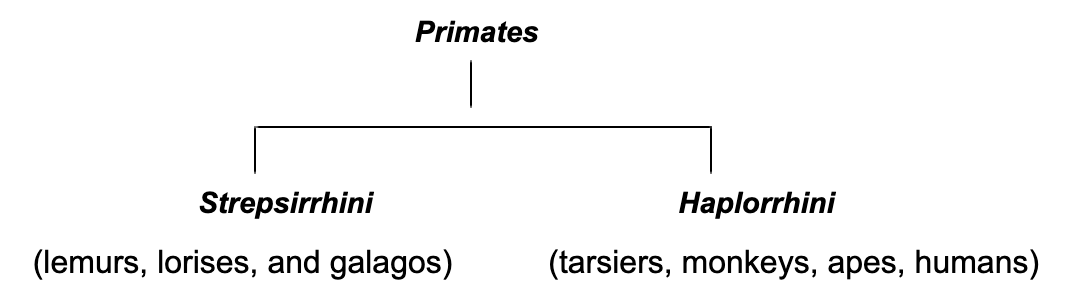

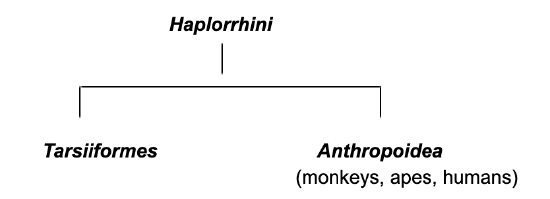

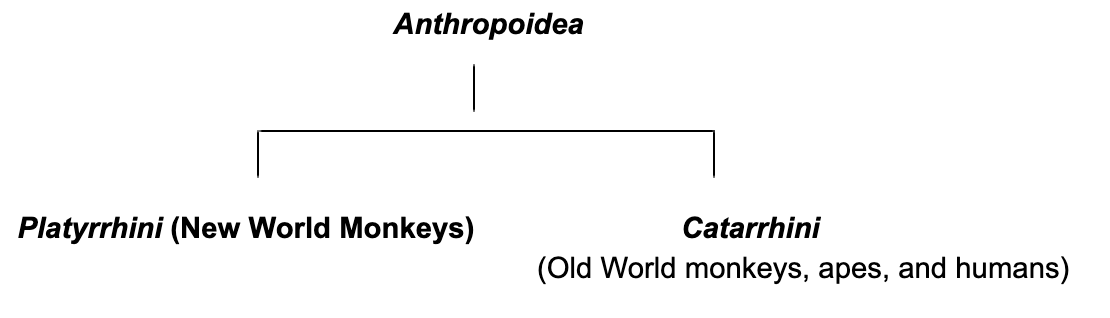

- Station 7: Students construct a primate order phylogeny based on the information from Stations 3 through 6.

- Instructors should have students report to the class on their answers for some/all of the stations. For example, each group could complete a small table for one station on the board. While some parts of the tables are more open-ended, there are some traits that instructors will want to be sure students identified correctly.

Conclusion

By completing this lab, students learn to distinguish primate and non-primate body forms and functions, with a focus on postcrania, teeth, and eye orbits. Students learn how to differentiate the primate suborders (Haplorrhini and Strepsirrhini) and to describe the unique characteristics of tarsiers, New World primates, and Old World primates. By the end of this lab, students will have acquired a robust understanding of primate classification.

Adapting for Online Learning

This activity could be easily adapted to online classes by linking to 3-D images of primates at educational sites (e.g., eSkeletons) and students could share their results in an assignment, virtual meeting (e.g., Zoom), or on an LMS discussion board.

References

Etting, Stephanie. 2019. “Chapter 5: Meet the Living Primates.” In Explorations: An Open Invitation to Biological Anthropology, edited by Beth Shook, Katie Nelson, Kelsie Aguilera, and Lara Braff. Arlington, VA: American Anthropological Association. http://explorations.americananthro.org/

Primate Classification Worksheet

Introduction

People belong to the zoological order Primates, which is one of the many orders within the class Mammalia. This lab provides the opportunity to observe characteristics of the skeleton that differentiate primates from other mammals, and compare primates to each other.

Before beginning, consider the following: What can bones tell us about the animal to which they belonged? Specifically, what might the skeleton tell us about:

- what the animal ate?

- its mode of locomotion?

- the kind of environment it lived in?

- its behavior?

Bones can reflect the lifestyle of primates, and the characteristics they share are likely reflective of early primate ancestors. For example, most primates move about in trees by grasping with their feet and hands. Primatologists believe the common ancestor of all living primates was an arboreal climber with prehensile extremities, who relied on vision more than olfaction (smell). This ancestor may have had some depth perception made possible by the overlapping visual fields of forward-facing eyes, and hands with the ability to manipulate objects. Thus, physical traits that help us distinguish primates from other mammals include:

- a generalized skeletal structure for arboreal life;

- convergent eyes (forward-facing);

- eye orbits with a postorbital bar or plate;

- reduced snout length (related to less reliance on smell);

- opposable thumbs and big toes;

- flattened nails instead of, or in addition to, claws;

- larger brain size

- differences in tooth morphology (reflects variable diets);

- and prehensile (grasping) hands and feet.

Station 1: Primate Versus Non-Primate Postcrania

Look at the skeletons or skeletal images provided. Note how the postcrania (body) of primates and non-primates differ. Carefully examine the vertebral column (backbone), the structure of the shoulder and pelvis, the shape of the rib cage, and the hands and feet. Think about what you already know about their locomotion and behavior for clues about how they move and the differences you may see on their skeleton. Record general observations in the table below.

| |

Non-Primates

(Ex. dog, cow, pig)

|

Primates

(Ex. monkey)

|

| Hands and feet |

|

|

| Claws or nails |

|

|

| Vertebral column and rib cage |

|

|

| Clavicle |

|

|

| Pelvis |

|

|

How do the above characteristics suggest the locomotion and posture of primates differ from non-primates?

Station 2: Non-Primate and Primate Teeth and Skulls

Mammals typically have four different kinds of teeth: incisors, canines, premolars, and molars. Examine the teeth of the primates (monkey and human) and non-primates (cow or pig and dog). While they all have a mixture of incisors, canines, premolars, and molars, what differences do you see between the species? (Number of teeth? Shape? Cusp pattern?) What might these features tell us about their function?

| |

Non-Primates |

Primates |

| Cow/Pig |

Dog |

Monkey |

Human |

| Distinguishing features of the teeth |

|

|

|

|

| Draw the tooth row shape |

|

|

|

|

| Probable diet |

|

|

|

|

The orbit is the bony structure that protects the eye. All living primates have a complete bony ring around the eye, but the orbit can be either open (postorbital bar) or closed (postorbital plate) in the back. Examine the orbits and their orientation. What differences do you see? Look at the foramen magnum: What does this tell you about the typical posture of the animal? Finally, look at the nasal region. Does this tell you about what senses they use most?

| |

Non-Primates |

Primates |

| Cow/Pig |

Dog |

Monkey |

Human |

| Eye orbit structure and orientation |

|

|

|

|

| Foramen magnum position |

|

|

|

|

| Size and complexity of nasal region |

|

|

|

|

| Rely more on vision or smell? |

|

|

|

|

Station 3: Primate Suborders: Strepsirrhini and Haplorrhini

Most modern strepsirrhines live on the island of Madagascar (lemurs), but a few stalk the night forests of Africa (galagos) and Asia (lorises). Our own suborder (haplorrhines) live in Asia, Africa, and the Americas. It is easy to talk about ourselves as if we are higher, grander, further up the scale, etc., but evolution results from adaptation to the immediate environment without a predetermined direction. So don't be specio-centric! After all, Loris tardigradus (a strepsirrhine) is much cuter than Cacajao rubicundus (a haplorrhine)!

| |

Strepsirrhine |

Haplorrhine |

| Nails or claws? Which digits? |

Claw on second digit, nails on others |

Nails only |

| Postorbital bar or plate? |

|

|

| Orientation of eye orbits (forward or toward the side) |

|

|

| Snout length relative to brain size |

|

|

| Presence or absence of tooth comb |

|

|

| Geographic location (read intro above) |

|

|

Station 4: Tarsiers

For some time, tarsiers challenged primatologists with regard to their classification: Were they closer to monkeys, apes, and humans or closer to lemurs and lorises? Genetic evidence has now provided strong support for the classification of tarsiers as haplorrhines, but their ancestors likely split off early, before the division of different types of monkeys and apes. Examine the tarsiers—what traits may have been confusing to primatologists because they are similar to lemurs and lorises or are unique to the tarsier?

| |

Tarsier |

Is this trait more like strepsirrhines or haplorrhines, or is it unique? |

| Nails or claws? Which digits? |

Grooming claw, and nails on other digits |

|

| Postorbital bar or plate? |

|

|

| Orientation of eye orbits (forward or toward the side) |

|

|

| Snout length relative to brain size |

|

|

| Presence or absence of tooth comb |

|

|

| Geographic location |

Asia |

N/A |

Station 5: New World Monkeys

Anthropoids are divided into two infraorders: Catarrhini (Old World monkeys, apes, and

humans, all who live in Africa and Asia) and Platyrrhini (New World monkeys who live in Mexico, Central, and South America). The word "monkey" is confusing because monkeys in the Americas are not closely related to Old World monkeys (Old World monkeys are, in fact, more closely related to people!)

| |

New World Monkey |

Catarrhine |

| Meaning of scientific name |

“Broad-nosed”

(separated by wide nasal septum)

|

“Hook-nosed”

(nostrils are close together)

|

| Direction nostrils face |

Look at photographs |

Look at photographs |

| Dental formula |

|

|

|

Geographic location

(read intro above)

|

|

|

Questions:

Some New World monkeys (Atelinae) have prehensile tails. Look up the name of one monkey that has a prehensile tail: ___________________________________________

One group of New World monkeys, Callitrichidae (marmosets and tamarins), have re-evolved claws on all but one digit. Which digit? (Do some research to find out!) ______________________________________________________

There is one group of New World monkeys who have a reduced or absent thumb. What type of monkey is this? _______________________________

Station 6: Old World Monkeys and Hominoids

| |

Cercopithecoid |

Hominoids |

| Old World Monkey |

Ape (e.g., chimpanzee) |

Human |

| Shape of rib cage |

|

|

|

| Length of forelimb (arm) relative to trunk |

|

|

|

| Length of clavicle and location of scapula |

|

|

|

| Presence or absence of tail |

|

|

|

| Lower molar cusp pattern (Y5 or bilophodont) |

|

|

|

The differences between the monkey skeletons and the hominoids may be because the common ancestor of apes and people was adapted for suspending the body by the arms and brachiating. The forelimbs are long, the shoulders are flexible, the elbows and wrists allow greater rotation, the chest is wide for the attachment of expanded forelimb retractor muscles, and the lower back is short. Cercopithecoids, on the other hand, are adapted to quadrupedalism, like most mammals. The bilophodont molar is their specialization for eating a wide variety of foods.

Station 7: Putting It All Together

Using what you have learned at Stations 3 through 6, construct the complete tree for the Primates order. Put primates at the top, divide them into strepsirrhines and haplorrhines, and then work your way down, dividing them into subgroups as you go. Use the tree in your textbook if you need help. Then, for each group on the tree identify at least one trait that helps distinguish that group.