14: Performance (Griffith and Marion)

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 20910

Performance

Lauren Miller Griffith, Texas Tech University

https://www.depts.ttu.edu/sasw/People/Griffith.php

Jonathan S. Marion, University of Arkansas

Learning Objectives

- Identify cultural performances and performances of culture in various settings.

- Explain the various reasons that anthropologists study performance.

- Describe the role of performance in both reflecting and contributing to social change.

- Define “presentation of self.”

- Articulate the relationship between performance and cultural constructions of gender.

- Analyze social conflicts using a theatrical lens.

- Differentiate between descriptive and performative utterances.

- Evaluate the outcomes of performance, especially as they relate to hegemonic discourses.

- Recall framing devices that are used to mark the boundaries of performance.

- Define intertextuality.

It’s finally here—after weeks of waiting, your favorite band is playing in concert tonight! Driving in, parking, passing by all the vendors, and getting to your seats is all a swirl of sights, sounds, smells, and textures. Your view is temporarily blocked and then opens up again amidst the jostling bodies all around. You smell the cologne of someone nearby and smoke on someone else, all as you yell over the opening band’s tunes to steer your friends to the correct seats. You’d set up two of your friends on a blind date for this concert, Jayden and Dakota, and from their grooming to their outfits to their flirtatious banter, both seem invested. The concert lives up to all your expectations! However, based on all the little cues—from leaning in toward each other to sideways glances—it looks like it was an even better night for Jayden and Dakota.

As you learned in earlier chapters, whether a night out is a “concert” or a “date” (and the appropriate behavior for each) is part of the learned and shared system of ideas and behaviors that comprise culture. The events—sporting events, shows, rituals, dances, speeches, and the like—are clearly cultural performances. At the same time, though, these activities and the interactions they involve are replete with culturally coded and performed nuances such as the lingering eye contact of a successful first date. In other words, there are two types of performances associated with our interactions with others: cultural performances (such as concerts) and performances of culture (such as dating). This chapter looks at both types of performance, exploring the different ways culture is performed and the effects of such performances.

OVERVIEW

In anthropological terms, a performance can be many things at once. It can be artful, reflexive, and consequential while being both traditional and emergent.1 As a result, each performance is unique because of the specific circumstances in which it occurs, including historical, social, economic, political, and personal contexts. Performers’ physical and emotional states will influence their performances, as will the conditions in which the performance takes place and the audience to whom the performance is delivered. At the same time, every performance is part of a larger tradition, and the creator, performer(s), and audience are all interacting with a given piece of that larger body of tradition. Performance is consequential because its effects last much longer than the period between the rising and falling of a curtain. The reflexive properties of performance “enable participants to understand, criticize, and even change the worlds in which they live.”2 In other words, performances are much more than just self-referential; they are always informed by and about something.

Despite the importance of performance in our social worlds, it was only in the mid-twentieth century that anthropologists embraced performance as a topic worthy of study. Visual arts received serious attention from anthropologists much earlier, in large part because of Western cultural biases toward the visual and because those tangible artifacts lent themselves to cultural categorization and identification. In the 1950s, Milton Singer introduced the idea of cultural performance. Singer noted that cultural consultants involved in his fieldwork on Hinduism often took him to see cultural performances when they wanted to explain a particular aspect of that culture.3 Singer checked his hypotheses about the culture against the formal presentations of it and determined that “these performances could be regarded as the most concrete observable units of Indian culture.”4 He concluded that one could understand the cultural value system of Hinduism by abstracting from repeated observations of the performances. In other words, (1) cultural performances are an ideal unit of study because they reference and encapsulate information about the culture that gave rise to them, and (2) the cultural messages become more accessible with each “sample” of the performances since the researcher can compare the specifics of repeated features of the same “performance.”

Singer’s observation that analyzing performance could be a useful method for understanding broader cultural values was revolutionary at the time. Today, anthropologists are just as likely to study performance itself—how performances become endowed with meaning and social significance, how cultural knowledge is stored inside performers’ bodies.5 Anthropology’s increased openness to treating performance as a worthy area of inquiry reflects a shift from focusing on social structures of society that were presumed to be static to examining the ongoing processes within society that at times maintain the status quo and at other times result in change.6

Cultural Performance vs. Performing Culture

When describing the anthropology of performance, two concepts are often confused: performing culture and cultural performance. Though they sound similar, the difference is significant. Richard Schechner, a performance studies scholar whose work frequently overlaps with anthropology, provides a useful distinction between these terms by distinguishing between analyzing something that is a performance versus analyzing something as a performance.7 A cultural performance is a performance, such as a concert or play. Performing culture is an activity that people engage in through their everyday words and actions, which reflect their enculturation and therefore can be studied as performances regardless of whether the subjects are aware of their cultural significance.

Mexico’s famed ballet folklorico is one example of a cultural performance (see Figure 1). In essence, it is an authoritative version of the culture that has been codified and is presented to audiences who generally are expected to accept the interpretation. Cultural performances typically are readily recognizable. Their importance is highlighted by the fact that they take place at specific times and places, have a clear beginning and end, and involve performers who expect to demonstrate excellence.8

The umbrella of cultural performances includes many events thought of as performances in the West (e.g., concerts, plays, dances) but also includes activities such as prayers and rituals that westerners would classify as religious practices. That some cultures, particularly in the West, make a distinction between a performance and a religious practice fits with a tendency to see some practices as spurious and others as genuine, one of the reasons anthropologists have only recently begun to study performing arts seriously. Singer found that each cultural performance “had a definitely limited time span, or at least a beginning and an end, an organized program of activity, a set of performers, an audience, and a place and occasion of performance.”9 The same is true for religious and secular events. Cultural performances are informed by the norms of one’s community and signal one’s membership in that community.

Cultural performances contribute to preserving the heritage of a group, and in some cases, they have the same effect as an anthropologist writing in the “ethnographic present” by providing an artificially frozen (in time) representation of culture. For example, among people living along the Costa Chica of Mexico, artesa music and the accompanying dance performed atop an overturned trough retains a strong association with the region’s African-descended population.10 The instruments and rhythms used in this music reflect the African, indigenous, and European cultures that gave rise to these blended communities and thus represent a rich, emergent tradition. In recent years, however, the artesa mostly is no longer performed at weddings, as was traditional, and performers are now paid to represent their culture in artificial settings such as documentaries and cultural fairs.

Performing culture refers to lived traditions that emerge with each new performance of cultural norms—popular sayings, dances, music, everyday practices, and rituals—and it takes shape in the space between tradition and individuality. Using our initial example, the concert Jayden and Dakota attended was a cultural performance while their dating behaviors were examples of performing culture. Obviously, no two dates are identical, but within a given social group there are culturally informed codes for appropriate behavior while on a date and for the many other interactions that commonly occur between people.

EVERYDAY PERFORMANCE

There is a constant tension between hegemony and agency in our everyday activities. For example, while you choose how you want to dress on a given day, your choice of what to wear is shaped by the social situation. You wear something different at home than you do when going to work, to the beach, to a concert, or on a date. The range of what is considered acceptable attire in different

social settings is an example of hegemony—for instance, a suit would be expected for a professional conference whereas a bathing suit would be entirely inappropriate (compare, for instance, Figures 2 and 3). An individual’s choice within the culturally defined range of appropriate options is an example of how agency—an individual’s ability to act according to his or her own will—is constrained by hegemony. Getting dressed is an example of an everyday performance of culture. When Jayden and Dakota paid extra attention to their appearance in anticipation of their date, they demonstrated—performed—their interest in pursuing a romantic relationship.

On the surface, our everyday performances probably seem inconsequential. A single failed performance may lead to an unfulfilling evening but usually does not have long-lasting consequences. However, when we look at patterns of everyday performances, we can learn much about a culture and how members of groups are expected to behave and present themselves to others. The subfield of visual anthropology is based on the notion that “culture can be seen and enacted through visible symbols embedded in behavior, gestures, body movements, and space use.”11

Presentation of Self

Sociologist Erving Goffman coined the phrase presentation of self to refer to management of the impressions others have of us.12 People adopt particular presentations of self for many reasons. A couple who aspires to be upwardly mobile, for example, may subsist on ramen noodles in the privacy of their apartment while spending conspicuously large amounts of money on fine food and wine in the company of people they want to impress. A political candidate from a very wealthy family might don work clothes and affect a working class accent to appeal to voters from that demographic or make a political appearance at a “working class” bar or pub rather than a country club. In many cases, people are not being intentionally deceptive when they adopt such roles. It is normal to act differently at home, at school, and at work; behavior is based on the social and cultural context of each situation. Goffman thus notes that impression management is at times intentional and at other times is a subconscious response to our enculturation.

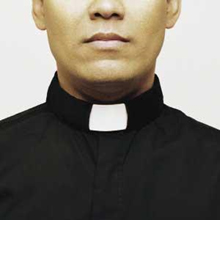

Goffman uses theatrical terms to discuss impression management when distinguishing front and back spaces. Front spaces are arenas in which we carefully construct and control the audience’s perception of the actors while back spaces are private zones where actors can drop those pretenses (see Figure 4). The front includes the setting—the physical makeup of the stage, including the furniture, décor, and other props, that figuratively, if not literally, set the stage for a social interaction.13 For

example, a restaurant and a church are both designed to seat tens or even hundreds of people and sometimes serve wine, but they are easily identified by how the seating is arranged, the kind of music played, and the artwork on the walls. Thus, presentations of the self also tend to be defined in part by the physical environment. Waiters adopt their role when they step into the restaurant and step out of those roles when they leave at the end of their shifts.

Another important component of these performances is the personal front: aspects of one’s costume that are part of the actor’s body or worn in close association with it.14 Clothing, physical characteristics, comportment, and facial expressions all contribute to one’s personal front. Some of these traits, such as height, are unlikely to change from one performance to the next. Others, such as a priest’s collar, a doctor’s white lab coat, a ballroom dancer’s dress, and a waiter’s convivial smile, can be changed at will (see Figure 5). Changes in the personal front affect the audience’s interpretation and understanding of the role played by the individual and their beliefs about the “actor’s” sincerity.

The match between the setting and one’s personal front helps the audience quickly—and often accurately—understand the roles played by the actors in front of them. But each actor’s performance still must live up to the audience’s expectations, and a mismatch between expectation and execution can result in the actor being viewed as a failure. Take the example of the college professor. She could be a leading expert in her field with encyclopedic knowledge of the course topic, but if she stutters, speaks too softly, or struggles to answer questions quickly, her students may underestimate her expertise because her performance of an expert failed.

In some roles, the effort to manage an impression is largely invisible to the audience. Imagine, for example, a security guard at a concert. If everything goes well, the security guard will not have to break up any fights or physically remove anyone from the concert. If a fight does break out, a small individual trained in martial arts might be best-suited to diffusing the situation, but security personnel are often large individuals who have an imposing presence, a personal front that matches the public’s expectations. A security guard could easily keep an eye on things while sitting still but instead usually stands with arms folded sternly across the chest or walks purposefully around the perimeter to make her presence known. She may make a show of craning her neck for a better view of certain areas even if they are not difficult to see. These overt performances of a security guard’s competence are not necessary for the job, but their visibility discourages concert attendees from misbehaving.

Social actors differ in the degree to which they believe in both 1) the social role in question, and 2) their individual ability to performance that specific role. Those who Goffman called “sincere” performers are both confident in their ability to play the role and believe in the role itself. A shaman, for example, who believes wholeheartedly that she has been called to heal the members of her community is likely to both believe in the role of a shaman and in her particular ability to fulfill that role. Some begin as sincere performers but later become cynical. Religious roles sometimes fall into this category; the performer loses some degree of sincerity as the religious ceremonies are demystified.15 Others are cynical in the beginning but grow into their roles, eventually becoming sincere. This is often the case with someone new to a profession. In the beginning, she may feel like a fraud due to lack of experience and worry about being discovered. Over time, the individual’s confidence grows until the role feels natural.

Case Study: VH1’s “The Pickup Artist”

The popularity of makeover television shows in recent years suggests that there is significant interest in learning to present an idealized version of oneself to others. In 2007, VH1 produced a reality show called “The Pickup Artist” that focused on men who experienced difficulty talking to women or who repeatedly found themselves viewed by women as “just friends” rather than as potential romantic partners. At the beginning of the season, the men were dropped off at a new house in a bus that said “Destination: Manhood” on the front, suggesting that their performance of masculinity was somehow lacking. The show’s host was an author and self-proclaimed pickup artist named Mystery who had overcome challenges connecting with women and was there to share his hard-earned knowledge with others. In the initial episode, the men were filmed in a club as they approached women. Oblivious to the cues the women were sending them, all of the contestants blundered through painfully awkward social interactions in which several of the women eventually just walked away. Behind the scenes, Mystery and fellow pickup artists observed and commented on the contestants’ attire, their approaches, and their conversation strategies. After diagnosing the contestants’ “problems” interacting with women, Mystery taught them specific strategies for things like “opening a set” (initiating a conversation) and “the number close” (securing a woman’s phone number). Though presented as a competitive reality show with one contestant ultimately being named “Master Pickup Artist” and receiving $50,000 to invest in his new identity, the show also revealed the level of performance expected within front-space areas such as nightclubs and how they differed from back-space areas such as the communal house, where contestants were (presumably) able to relax without having to micromanage their presentations of self.

Performance of Gender

As you may recall from the Gender and Sexuality chapter, gender is defined by culture rather than by biology. Gender theorist Judith Butler’s term “gender performativity” references the idea that gender as a social construct is created through individual performances of gender identity. Butler’s key point, published originally in 1990 and expanded in 1993, is that an act is seen as gendered through ongoing, stylized repetitions.16 In other words, while we all make specific choices—such as how Jayden and Dakota chose to dress for their date—people doing things in patterned ways over time results in certain versions being typified as “male” or “female.” Phrases such as “act like a man” or “throw like a girl” are good examples. Socially, we define certain types of behavior as typical of men and women and culturally code that behavior as a gendered representation. Thus, specific individuals are seen as doing things in a particularly (or stereotypically) masculine or feminine way. How do you know how “men” and “women” are supposed to behave? What makes one way of sitting, standing, or talking a “feminine” one and another a “masculine” one? The answer is that definitions of masculine and feminine vary with the socio-cultural milieus, but in every case, how people commonly do things constitutes gender in everyday life.

In many ways, the notion that gender is created and replicated through patterned behavior is an expansion of Marcel Mauss’ classic idea that the very movements of our bodies are culturally learned and performed.17 Walking and swimming may seem to be natural body movements, but those movements differ in individual cultures and one must learn to walk or swim according to the norms of the culture. We also learn to perform gender. If you showed up to the first day of class and all of the men in the class who had facial hair wore sundresses, you would notice and be surprised or confused. Why? Because, as Butler pointed out, gender is constructed through patterns of activity, and a bearded man in a sundress deviates from the expected pattern of male attire. While this is a particularly obvious example, the mechanism is the same for much more subtle expectations regarding everything from how you walk and talk to your taste in clothing and your hobbies. In Western contexts, for instance, athletic prowess is typically coded as masculine. But as Iris Marion Young noted, it is impossible to throw like a girl without learning what that means.18 The phrase is not meant to refer to the skills of pitcher Mo’ne Davis who, at thirteen years old, became the first female Little League player to appear on the cover of Sports Illustrated in August 2014.19 Young’s point, by extension, is twofold: 1) “girls” only throw differently from “boys” insofar as they are taught to throw differently; and 2) what counts as throwing like a girl or a boy is a learned evaluation. Taking the idea a step further, several scholars looked at performance of gender in a variety of sports, including women’s bodybuilding, figure skating, and competitive ballroom dancing. In each case, some aspect of femininity is over-performed through blatant makeup and costuming to compensate for the overt physicality of the sport, which is at odds with stereotypical views of femininity.20

As anthropologist Margaret Mead first publicized more than 80 years ago, what counts as culturally appropriate conduct for men and women is quite different across cultural settings.21 More broadly, Serena Nanda provided an updated survey of cross-cultural gender diversity.22 Two issues are particularly important: 1) the Western concept of binary gender is far from universal (or accurate); and 2) all behaviors are performed within—and hence contingent upon—specific contexts. For example, Nanda’s work in India documents the ability to perform a third gender.23 Similarly, Gilbert Herdt’s work among the Sambia in Papua New Guinea counters the idea of sexual orientation as fixed (e.g., heterosexual, bisexual, homosexual) and provides a counter-example in which personal sexuality varies for boys and men by stage of life.24 Perhaps the most compelling case for performance of gender is the Brazilian Travesti, transgendered male prostitutes who, despite having female names, clothing, language, and even bodies achieved through silicone injections and female hormones, identify themselves as men.25 These cases demonstrate that sexuality is different from gender and that gender, sexual orientation, and sexuality are performed in daily life and at moments of heightened importance such as pride parades.

Case Study: Small Town Beauty Pageants

Oh to be the Milan Melon Queen, the Reynoldsburg Tomato Queen, or even the Circleville Pumpkin Queen, these are the dreams that childhood are made of!

Beauty pageants provide communities with opportunities to articulate the norms of appropriate femininity for the contestants and spectators. Pageant contestants are judged on their ability to perform specific markers of conventional femininity. In local pageants associated with community festivals (i.e., winners do not progress to larger regional and national competitions), contestants are expected to “perform . . . a local or small town version” of this ideal according to performance-studies scholar Heather Williams.26 In these settings, success is predicated on demonstrating one’s poise and confidence as a representative of the community.27 Those competing in regional, state, and national competitions like Miss America often spend years being groomed for competition and developing a stage presence meant to transcend small town ideals of femininity. A striking difference between the national pageants and many local ones is the swimsuit competition in the national pageants. Perhaps local organizers are reticent to objectify young women from their own communities or because of small town conservatism. Anthropologist Robert Lavenda points out that a town may not be seeking to crown the most beautiful contestant and instead seeks the one who will best represent the community and its values.28 Judges evaluate contestants not on their physical attractiveness per se but on how well their “presentation of self” aligns with the community’s views of who they are.

Lavenda identified several characteristics shared by contestants. Though the competitions are generally open to women age 17 to 21, the majority who competed had just finished high school, making them all part of the same cohort leaving childhood and entering adulthood. All had been extremely active in extracurricular activities and were pursuing post-secondary education. Furthermore, because they needed sponsors to compete, the local business community had vetted all in some way. While contestants at the national level have private coaches and train independently for competitions, contestants in local pageants often work together for weeks or months before the festival, learning how to dress, walk on stage, and do hair and makeup. The result is a homogenized presentation of self that fits with the community’s expectations, and the ideal contestant represents “a golden mean of accomplishment that appears accessible to all respectable girls of her class in her town and other similar small towns.”29 If the winner chosen does not represent those qualities or behaves counter to the prevailing values of the community, the audience often becomes upset, sometimes alleging corruption in the judging.30 While the competition is ostensibly about the contestants and their ability to perform a certain ideal of femininity, it also demonstrates “the ability of small towns to produce young women who are bright, attractive, ambitious, and belong—or expect to belong—to a particular social category.”31 At least during the competition, unsuccessful performances of the feminine ideal are pushed out of sight and mind.32 This, the community tries to show, is what our women are like.

Social Drama as Performance

Goffman used a theatrical metaphor to analyze how individuals change their presentations of self based on the scenic backdrop—front stage versus backstage. Anthropologist Victor Turner was more interested in the cast of characters and how their actions, especially during times of conflict, mirrored the rise and fall of action in a play.33 As already noted, everyday life is comprised of a series of performances, but some moments stand out as more dramatic or theatrical than others. When a social interaction goes sufficiently awry, tensions arise, and the social actors involved may want to make sure that others understand precisely how expected social roles were breached. Turner calls these situations “metatheater,” and they are most clearly seen in and described as social dramas: “units of aharmonic or disharmonic social process, arising in conflict situations.”34

A social drama consists of four phases: breach, crisis, redress or remedial procedures, and either reintegration or recognition and legitimation of an irreparable schism.35 A breach occurs when an individual or subgroup within a society breaks a norm or rule that is sufficiently important to maintenance of social relations. Following the breach, other members of the community may be drawn into the conflict as people begin to take sides. This is the crisis phase of the social drama. Such crises often reignite tensions that have been dormant within the society.

The redressive or remedial procedures used can take a number of forms. It is a reflexive period in which community members take stock of who they are, their communal values, and how they arrived at the conflict. The procedures used during this phase may be private, such as an elder offering sage advice to the parties centrally involved in the conflict. Other procedures are public, such as protests in the town square, formal speeches, and public trials. The Salem witch trials are an example of a public means of redress. This phase can also include payment of reparations or some form of sacrifice.

The final phase takes one of two forms. If the redressive actions were successful, the community will reintegrate and move beyond the schism (at least until another breach occurs). If the redressive actions were not successful, the community will fracture along the lines identified during the crisis phase. In smaller societies characterized by a high degree of mobility, individuals may physically move away from one another. In other groups, the two camps may erect barriers to prevent interactions. Social dramas are important events in communities and can be source material for other kinds of performances such as narrative retellings and commemorative songs and plays, all of which further legitimize the outcome of the social drama.36

Case Study: Establishing a New Capoeira Group

Capoeira is an Afro-Brazilian martial art that combines music, dance, and acrobatics with improvisational sparring. The traditional bearers of capoeira kept it alive despite persecution from the colonial Portuguese government and the Brazilian government until the mid-1930s. Even after that date, it was mostly associated with marginalized segments of the population. However, in the 1970s, several Brazilian capoeiristas began demonstrating and teaching their art abroad. This sparked international interest in capoeira and demand for teachers in nations such as the United States continues. In many cases, the teachers are apprentices to more established mestres (masters) in Brazil and maintain ongoing relationships with them.

While the teachers may continue to operate satellite groups under the primary mestre’s direction for years, tensions can erupt between a mestre in Brazil and the teachers abroad. This is precisely what happened with a group referred to here as Grupo Cultural Brasileiro (GCP). The mestre of GCP authorized one of his top students to begin teaching capoeira classes in a midwestern U.S. state. Eventually, demand for the classes grew, allowing the teacher to operate classes in two towns in the state, and two of his students were given the opportunity to start classes in new locations. All of the satellite groups were affiliated with the GCP; individuals wore shirts with the GCP logo and the mestre periodically visited the United States to give classes to the American students. Unbeknownst to most members of the group, the teacher and mestre had a falling out after one of the visits. The mestre had asked his teacher for a small sum of money (approximately $2,000) to pay for some repairs on the primary training facility in Brazil. The teacher agreed that it was a worthwhile expenditure but insisted that they had to discuss it with the U.S.-based board of directors before he could send the funds. Feeling that his authority was being slighted, the mestre demanded that certain individuals who he viewed as obstacles be removed from the board, and when the teacher explained that this was not possible according to the group’s bylaws, the mestre demanded that the group stop wearing the GCP logo. This disagreement constituted a breach under Turner’s model.

Several weeks later, an emergency board meeting was called to determine the proper course of action. In response, the mestre called the teacher’s protégés who were already teaching on their own and essentially asked them to take sides. The students were made aware of this crisis when, at one of their weekly classes, they were told to turn their t-shirts inside out so the logo would not show, and thereafter, they were not permitted to wear the shirts.

To resolve the conflict, the board, teacher, and mestre considered mediation, and the mestre and teacher spent considerable time talking about to various members of the community. These efforts at remediation failed, resulting in a schism. The students in the Midwest convened with the teacher, discussed the group’s values, and chose a new name and symbol to represent the group in the capoeira community at large. Now, nearly ten years later, the two groups continue to operate independently.

CONSTITUTING SOCIAL REALITY

In many cases, performances produce social realities. Imagine, for example, a political protest song that moves people to action, resulting in overthrow of a government regime. Similarly, performance can provide people with a template for action. For instance, people may model their relationships after ones they observe on television, and famous quotations from films get absorbed into everyday use and language. However, some performances stand out as more likely to shape social reality than others.

Performativity

Many performances are accomplished without words—mime and dance are two obvious examples. Often, though, language is used instrumentally to accomplish a specific task. Many utterances are simply descriptive (e.g., “that was a great concert!”) while others are actions that bring about an outcome by virtue of being spoken. To distinguish between utterances that do something and those that merely describe, linguist J. L. Austin coined the term performativity. For example, compare these sentences:

We hereby bequeath our vast fortune to our darling daughter.

The girl inherited money from her parents when they died.

The first is performative because it causes something to happen; it transfers money between persons. The second is merely descriptive; it shares information that may or may not be factual about an event that occurred independently.

A person making a performative utterance must be genuine in the intent to carry it out and have it ratified by interlocutors—co-participants in the speech event. For example, a mother might say to her son, “I promise we will get ice cream after the dentist appointment.” Making such a promise is a performative utterance because it creates a social contract, but her son may or may not believe her based on his prior experience. Likewise, if one makes a bet, the other party must agree to the terms. The bet is only on if the second party agrees.

Performative utterances commonly occur at wedding ceremonies.

Now that you have pledged your mutual vows, I, by virtue of the authority vested in me by the state, declare you to be wed according to the ordinance of the law.

Although wedding ceremonies typically involve numerous performances, such as a procession, songs, and lifting of the veil, the proclamation is the culminating moment in which the two individuals are legally joined in matrimony. Without these words being spoken, the ceremony is incomplete.

In addition to the performative declaration, the proclamation includes another important element: the authority granted by the state to make the declaration. Without this authority, a legal marriage does not occur. So a group of children playing can stage a wedding and say the exact same words and no one is married. In Austin’s terminology, the unofficial wedding proclamation is an “unhappy utterance.”37 It is a failed performance because the parties involved did not have sufficient authority to bring the action to reality. A parallel example is a lawyer declaring a defendant guilty, something only a judge or jury (in the correct setting) can declare with authority. The ability of an utterance to shape an individual or a society depends on the words said, the context in which they are said, and the legitimacy and authority of the speaker. Performative utterances occur in many situations and are particularly common in rituals.

Ritual as Performance

Consider a Cuban woman who is experiencing disharmony at home. Her husband is abusive, she struggles to put food on the table, and one of her children left home and is living on the street. To find a solution, she consults a priest of the syncretic religion Santería. In the consultation room is an altar with candles, statues of gods and goddesses, and bowls filled with food offerings. The priest is dressed in white, as is customary, and wears several beaded necklaces that correspond to the deities with whom he is most closely associated. To use Goffman’s phrasing, the setting and his personal front are congruent, assuring the woman that the consultation is genuine. To perform the divination, the priest tosses cowry shells on the table and asks the woman a series of questions based on what the shells reveal. He listens to her answers, throws the shells again, and fine-tunes his questions until he is able to focus on the crux of her distress. The flow of their dialog is similar to that seen in Western-style psychological counseling, but the ritual specialist performs his expertise using religious paraphernalia.

The Religion chapter introduced the concept of rituals and explained several of their functions, including rites of passage and of intensification. In this section, we call attention to rituals as an area of interest to cultural anthropologists who deal with performances and highlight how performance can be a useful lens for viewing and understanding secular and religious rituals. Obvious examples of rituals that inform anthropologists about a culture are concerts, plays, and religious events, which often portray cultural values and expectations, but rituals are involved in many other kinds of situations, such as trying and sentencing someone accused of a crime in the redressive phase of a social drama. The key here is that rituals are inherently performative. Merely talking about or watching a video recording of one does not do anything whereas participating in a ritual makes and marks a social change. Whether stoic or extravagant, a ritual is focused on efficacy rather than entertainment, and its performance gives shape to the social surrounding.

Case Study: Performing Ethnography

Ethnographies are written to engage readers in the lived experience of a particular group, but the reader cannot actually feel what it is like to live in a Ndembu village or smell herbs being prepared for an Afro-Brazilian Candomblé ceremony. Consequently, Victor and Edith Turner created a teaching method called “performing ethnography” to help students gain a deeper, kinesthetic understanding of what it is like to participate in the ritual life of another culture.38 Students prepare for the ritual by reading relevant ethnographies and often meet with anthropologists who have done work with the people who performed it. To prepare for the ritual, the students must seek additional information about the culture so they can understand how to behave appropriately. The process also encourages them to think critically about the presentation of information in ethnographies, especially if gaps in the author’s descriptions become apparent. Modeling an experiment after the Turners’ example, Dr. Griffith had students perform a Christian American wedding ceremony. Obviously, no single ceremony can be representative of all weddings within that tradition, but the students came away from the experience with a better sense of what it is like to participate in that ritual and how the various roles move the couple from one social status to another. As the Turners pointed out, a serious ritual can be conducted within what they called a “play frame”39 that negates the action otherwise brought by the ritual. So even though the woman who played the role of minister in the classroom “wedding” was in fact ordained, her words did not marry the individuals. The Turners have also used this method to allow students to better understand rituals such as coming of age ceremonies. Whether one can truly understand what it is like to be an initiate in such an important ritual without firsthand experience is doubtful, but the experience gives students an opportunity to reflect on their feelings as they participate in the rituals, providing the Turners with new hypotheses to explain how and why the rituals bridge childhood and adulthood that can be tested through further fieldwork.40

Political Performances

Performances have serious consequences for social reality and are often used to reinforce the status quo. For example, children in the Hitler Youth organization during World War II were encouraged to sing songs related to Germany’s supremacy and Hitler’s vision for an Aryan nation. Requiring children to give voice to this ideology brought them in line with the goals of those in power. Indeed, many civil rituals are part of such hegemonic discourses in which the basic parameters of social thought and action are unquestioningly (and usually invisibly) dictated by those in authority. Singing the national anthem before a sporting event is another example.

On the flipside, performances can be used to resist the status quo. These kinds of performances can be as subtle as a rolling of eyes behind a professor’s back or as grand as an outright political uprising. Pete Seeger’s song “Bring Them Home,” which protested the United States’ involvement in the Vietnam War, is a good example. Consider these lyrics: “Show those generals their fallacy . . . They don’t have the right weaponry . . . For defense, you need common sense . . . They don’t have the right armaments.” Those lines provide a clear indication of the singer’s political position, but repetition of the chorus “bring them home, bring them home” invites the audience to sing along, echoing and amplifying the singer’s message and thus increasing its political force.

BOUNDED PERFORMANCES

Although much of our interaction with others throughout the day involves performing various roles, there are moments of heightened reflexivity that are particularly recognizable as being commonly understood as “performances,” such as plays and concerts, which are special because they are marked off from everyday activities. In other words, they are bounded and analyzable. They are also short-lived. Even when such performances are fixed on film or through movement notation (such as Labanotation script, a system for recording dance movements), the interaction and feedback between an audience and the performer(s) happens “in the moment” only once. Because they are known and understood to be bounded, they often serve as moments of heightened consciousness. Jayden and Dakota, introduced at the start of this chapter, paid close attention to their first date because they knew that it was the only first date they could have together. Within such a state of heightened awareness, performers essentially hold a mirror up to society and force audience members to come to terms with themselves—as they are, as they once were, or as they could become.

Training/Rehearsal

Individuals such as shamans who are experts in performing rituals spend years mastering their crafts. Unfortunately, performance scholars have largely focused on final performances and ignored performers’ preparations. Scholar Richard Schechner, a pioneer in the study of performance, has advocated for a more holistic study of performance production that includes the training, workshops, rehearsals, warm-ups, performance, cool-down, and aftermath.41 The steps involved vary according to the culture in which the performance occurs.42

Rehearsal and training instill an embodied understanding of the art’s form and technique in the performer, and adherence to the forms gives performances their versatility and longevity.43 Techniques thus serve as a conservative force within a performance genre as each generation of performers learns to replicate the postures and movements of their predecessors.44 We do not suggest that performance traditions do not change. Indeed, as individuals master the form and become legitimate bearers of tradition, they have more and more latitude to play with the form and introduce innovations that may, in turn, be reproduced in the future by their protégés.

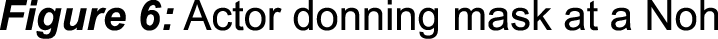

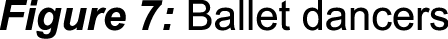

Some training requires a lifetime. For example, in the Japanese performance of Noh—a traditional music and dance performance featuring masked actors (see Figure 6)—training typically begins when an actor is around five years old.45 Because the actors have, in the process of their training, learned all of the necessary roles, there is little need for a cast to rehearse a drama in its entirety prior to performing it. This kind of training is also seen in classical Indian dance and other forms in which adherence to tradition is the norm. In other cases, audiences expect a continually changing repertoire of pieces that require the cast to rehearse extensively prior to the performance. Ballet dancers, for example, undergo extensive training for a relatively brief career, and the novelty of some performance pieces requires intensive study of new choreography prior to opening night.

The pressure felt by performers during shows are not present during rehearsals, which typically allow for an element of playfulness.46 Schechner thus likened rehearsals to rites of separation that occur within rituals.47 In his view, rehearsals are removed in space and time from the rest of society and allow performers to acquire the skills and knowledge needed to create a transformative, liminal experience for themselves and the audience when the performance is given. Thus, the spaces in which training and rehearsals take place are also important. Writing of the ballet studio (see Figure 7), scholar Judith Hamera, who studies performance, noted that “as surely as ballets are made in these spaces, the spaces themselves are remade in the process, becoming, perhaps through the repetition of this epitome of classical technique, a kind of Eden both inside and outside of everyday space and time.”48 This “construction” can be both a concrete process (the floors are scuffed by the dancers’ feet and the barres bowed by the weight of novices learning to plié) and a metaphorical transformation. The sacrifices of time and energy by the dancers sanctify the space. Even when the rehearsal space is merely a parking lot, empty field, or someone’s living room, the actions and intentions of those within the space give it meaning.

Framing Performance

Imagine sitting down with a group of young children. Their attention is focused on their teacher, who sits at the front of the room. There are many clues that it is story time—the children have moved from their desks to the floor and been told to sit quietly with their hands in their laps. But the unequivocal sign is the teacher saying “Once upon a time, in a land far, far away . . .” This is a familiar formula for people who grew up in American culture. It tells the audience that a fairy tale is about to begin and that the speaker is assuming responsibility for a suitable performance of the tale. With such a simple phrase, the participants in this interaction are cast in specific roles with clearly defined responsibilities. How will the story end? Most of us already know. The protagonist(s) will live “happily ever after.” This too is a formulaic phrase, one that signals conclusion of the performance. These are what Richard Bauman calls framing devices: cues that “signify that the ensuing text is a bounded unit which may be objectified.”49

Such frames are metacommunicative. They offer layered information about how to interpret the ensuing message. Examples of framing devices include codes, figurative language, parallelisms, paralinguistic features, formulas, appeals to tradition, and even disclaimers of performance.50 Codes are associated with particular types of performances. For example, a performance in which lines includes the words thee and thou signal to listeners that the performance involves religious speech or other old texts such as Shakespearian plays. Figurative language refers to illustrative words and phrases such as similes and metaphors that convey meaning in just a few words. Calling someone “a wolf in sheep’s clothing” alludes to a predator masked as prey, and no one familiar with the idiom would imagine this as a reference to a four-legged predator wearing a wool costume. Parallelism is repetition of sounds, words, or phrases used as a memory device or to build momentum. President Obama’s repetition of “Yes we can” in his campaign speeches is a good example of this. Paralinguistic features describe how words are delivered, such as an auctioneer’s signature speed of delivery. Formulas are stock phrases that give the audience information, such as “once upon a time” indicating that a story is beginning. Appeals to tradition, such as saying “this is how my dad always tells the story,” not only frame a performance but place the performance in an intertextual (a more detailed discussion of intertextuality follows) relationship with past performances. Finally, disclaimer of performance is denying that one is competent to perform and calls attention to the fact that a performance is about to occur or just occurred. These devices, used alone or in combination, give the audience the authority to judge the performer and distinguish the performance from the flow of events that preceding and following it.

Meaning Making

Typically, when constructing the meanings of bounded performance events, three primary interests are involved: the author(s), the artist(s), and the audience. In each case, the composition of those groups differs and the meaning of a performance can be quite different. Polysemy (derived from the Greek words for “many” and “sign”) is used in anthropology to describe settings, situations, and symbols that convey multiple meanings. This is certainly the case for performance events since a single form can be used in a variety of ways depending on the creators’ and/or performers’ intentions and the audiences’ framework for receiving and interpreting the piece.51 If artists intentionally subvert the author’s intentions, the audience could interpret a performance as ironic rather than sincere. Similarly, if an audience fails to understand the author’s intent, the message can fall flat or be received quite differently than intended by either the author or the performers.

The author of a performance and the artists who transform the author’s vision into a reality often have ambiguous positions in society. They may be admired for their skill and feared for their ability to transform social realities and disrupt the status quo.52 The author and artist can be the same individual (e.g., an author performing a monologue she wrote) or a group of artists can collectively author a work (e.g., the performance group Pilobolus).53 Most commonly, an author or authors creates the work and one or more artists perform it. In a ballet, for example, a dancer’s role is to carry out faithfully the vision of the choreographer, which may or may not happen. At times, artists in a performance have only a vague sense of who the author is, as when individuals recite folktales or proverbs that have been handed down across generations.

The audience consists of one or more individuals who cooperate with the performer(s) by temporarily suspending the normal communication rule of turn-taking and who gather specifically to observe the performance.54 Individuals come to a situation with unique background and experiences so the audience does not receive a performance uniformly. Similarly, as part of the context of a performance, the audience participates in constructing its meaning. Audience members evaluate the performance based on the formal features of the genre, holding performers responsible for demonstrating competence in the genre.55 For example, different criteria are used to evaluate acting in a drama versus a comedy. In in-person settings, artists are often influenced by the audience. A politician, for example, may phrase key points differently depending on the audience or choose particular jokes that will resonate with the demographic at hand in an effort to be judged positively.56 Adjustments may be made spontaneously in response to the audience’s reaction to earlier material.

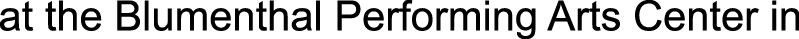

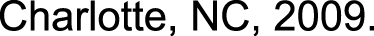

Linked to the audience, then, is the setting. Experiencing a performance of Romeo and Juliet outdoors under a tent is very different from experiencing the same play in a historic theater like The Globe in London (a reproduction of the Elizabethan-era theater where many of William Shakespeare’s plays were staged). The setting is important not only for context but for access. Performances in public parks or downtown squares (e.g. Figure 8) are accessible to all while performances at theaters and opera halls (e.g. Figure 9) are limited to people who have time and money to spend on such luxuries. Similarly, and as discussed previously, visual cues in a performance space are often important signals that a performance is occurring. If you see a couple in a park arguing loudly, wildly gesticulating, and drawing bystanders into their conflict, you may have stumbled onto an avant-garde theater production, but the lack of framing (no stage, curtains, or formal audience seats) makes the scene ambiguous. It may be only a couple arguing.

Clearly, then, there are many possible outcomes of a performance. Some are staged simply for entertainment, which is an important component of human life. Often, though, there are additional motivations behind the creation and performance. For example, a performance can be used to assert the distinctiveness of a particular ethnic group or to argue for racial harmony in a nation-state. Carla Guerron-Montero described such performances in Panama, which gained its independence from Colombia in 1903.57 The United States assisted the Panamanian separatist movement and participated in building the Panama Canal shortly thereafter. To distinguish themselves from Colombians and from U.S. citizens in Panama, middle-class intellectuals in Panama have consistently looked to Spain as the legitimate source of their identity. In this romanticized view, the ideal Panamanian is a rural, Hispanic (Spanish and indigenous) peasant, and peasant forms of dress (the pollera) and music (the tipica) are used to symbolize a unified national identity of pride in being a racial democracy. Along those lines and as performed in numerous everyday actions, Panamanian national discourse holds that mestizo (mixed) identity is normative, and they contrast themselves with other Latin American countries that have racial inequalities. Still, because lived life is always more complex than any single narrative, Afro-Panamanians still contend with discrimination.58

Case Study: Theater and Public Health Education

An approach known as Theater of the Oppressed was chiefly promoted by Augusto Boal, who was in turn influenced by Paulo Freire’s work on liberator education among oppressed peasants in Brazil. Boal used the term to refer to performances that engaged the audience in a way that transformed its members and influenced them to abolish oppressive conditions in their societies. Though originally conceived as a political action, Theater of the Oppressed has been applied to public education. Performance-studies scholar Dwight Conquergood, for example, spent time in Thailand at the Ban Vinai refugee camp developing a health education program.59 He started a performance company composed of Hmong refugees that used traditional cultural performances such as proverbs, storytelling, and folksong to produce skits about health problems in the camp. Conquergood wanted to avoid merely coopting local performance traditions and using them to essentially force Western ways of thinking on the refugees, which would establish a hierarchical model of education based on the idea that knowledge can simply be transferred from one who knows to one who does not.60 He wanted to engage the refugees in a dialog about how they could collectively improve the health conditions of the camp. Early on, the village was threatened by a potential outbreak of rabies, and when instructed to bring their dogs to sites around the camp for vaccination, the refugees did not comply because they did not understand the urgency of the situation or how the vaccines would help. Conquergood’s group of actors created a parade in which they dressed up as animals that were important in the Hmong belief system and played music to catch the villagers’ attention. When people came to see the parade, the chicken, an animal known for its divinatory powers, shared information about rabies and the importance of vaccinating dogs. The parade was successful in convincing residents to vaccinate their dogs and provided an opportunity for the villagers to give the actors constructive criticism about their performance. Their critiques increased the cultural relevance of future performances and made the villagers more invested in the activities of the theater troupe, further increasing their likelihood of success.

Recontextualized Performances

Established performances (such as a ritual or festival) occur in new and changing contexts. In line with Clifford Geertz’s understanding of cultures as “texts,” the term intertextuality describes the network of connections between original versions of a performance and cases in which the performance is extracted from its social context and inserted elsewhere. The conventional relationship between text and performance is that “the text is the permanent artifact, hand-written or printed, while the performance is the unique, never-to-be-repeated realization or concretization of the text.”61 In the anthropology of performance, a “text” is a symbolic work (literature, speech, painting, music, films, and other works) that is interpretable by a community. It is the source material, and the relationship between the text and a performance is mediated by many contextual factors, including previous experiences with the text, learning of the lines, rehearsals, directorial license.

Folklorist and anthropologist Richard Bauman asked what storytellers accomplish by “explicitly linking” their tales to prior versions of the source material.62 In short, Bauman found that linking situates each performance within the web of relationships among performances, which in turn adds to the performer’s credibility by demonstrating that the performer is connected in some way to the other performers or at least is knowledgeable of past performances. For example, a man singing a lullaby to his child might preface the song by explaining that it is one his father sang to him and that his father’s father sang before him. This places the father in a genealogical relationship with past performers and places the audience, his child, into that genealogy as well.

Alternatively, one can explicitly link a current performance to a prior one to invert what the audience knows about the past performance, as in a parody.63 In that case, anthropologists refer to how significantly one departs from faithful replication of the original source as the intertextual gap.64 A direct quotation of another’s words, such as a town crier relaying a king’s decree, has a narrow intertextual gap while a parody that references an original source to mock it, such as the 2014 film A Million Ways to Die in the West or the 1974 film Blazing Saddles that both poked fun at Westerns, has a large intertextual gap. Source material taken from one genre and used in another, such as a popular proverb turned into a song lyric, also has a large intertextual gap. Deliberate manipulation of these gaps—the recontextualization of source material—changes their role, significance, and impact in a performance.

Case Study: Intertextuality and the Coloquio

Richard Bauman and Pamela Ritch studied a coloquio (formal conversation) of a nativity play that has been performed in Mexico as far back as the sixteenth century.65 Although the play is often associated with the Christmas season, Bauman and Ritch reported witnessing its performance at the culmination of important community events in other seasons as well. The plays are long, often lasting twelve to fourteen hours, and involve a significant number of community members who volunteer their time to act, direct, and produce the spectacle. After parts are assigned, the actors must learn their lines. The words are already familiar to them as they have attended such plays since childhood, and the actors often model their deliveries on presentations they witnessed in the past. Six or seven rehearsals typically precede the formal public performance, and each is a full run-through with no opportunity to stop and rework a scene viewed as poorly done. However, a prompter reads from the script to assist the actors with their lines if necessary, thereby assuring a narrow intertextual gap. When relying on the prompter’s cues, the actors echo back the words, reinforcing the narrow gap. One character is an exception. In the written script, the hermit is a pious character. In the performance, however, the hermit is a comic figure. He rarely knows his lines and thus relies on the prompter’s cues, but instead of echoing them back faithfully, he intentionally substitutes words for comic effect. He alone is allowed to significantly depart from the script, creating a large intertextual gap that introduces humor into the performance that is absent from the script—and in a way that is impossible to sustain across multiple performances of the play if it were ever “frozen” into the script. A joke, after all, is funny only so many times before becoming boring from repetition.

Performance Communities

Cultural performances are informed by the norms of one’s community of practice and signal one’s membership in the community.66 Thus, the study of performance is not limited to what happens on a stage or within the limits of Bauman’s frames. Rather, studies of performance allow us to see the environment in which the performance occurs as a space in which identity is formed by both accommodating and resisting social norms even as they are being rehearsed and learned.67 In large, industrialized societies, people often elect to become part of smaller communities of practice around which they build their identities. Each of those communities has its own “folk geography,” a term used by performance scholar Judith Hamera to describe the shared knowledge of where to shop for dance-related paraphernalia and which medical practitioners in town best understand dancers’ bodies.68 Folk geographies are all-encompassing. They are global geographies that include historical markers redolent with meaning for the community, the locations of key teachers and everything else a practitioner needs to know to navigate the community.

Sociologist Howard Becker’s exploration of “art worlds” highlights how the obvious activity—painting or playing a musical instrument, for example—is contingent on and contextualized by a larger community that provided the materials, training, venues, and audiences for all such art practices. Wulff has extended this concept to the ballet world and by Marion to the ballroom and salsa world.69 More than simply suggesting that performances happen within communities, the point is that communities emerge and grow around specific performance practices. Indeed, for something to become a genre rather than simply an individual variation, other people must become involved. New styles emerge only when variations find an appreciative audience and then are copied or modified by others. Over time, however, as a style grows in popularity and is shared more widely, broader and deeper cultural elaborations may develop. This has been the case with salsa dancing, which is now both a worldwide phenomenon and a local practice.70

Performance in the Age of Globalization

In this age of globalization, communications and interactions among people in vastly different geographical locations have sped up and grown dramatically thanks to ever-faster and more-ubiquitous communication and transportation technologies. Globalization is not a new phenomenon but has greatly intensified in recent decades, creating links between producers and consumers, artists and audiences, which were not possible in the past. And as emphasized in this chapter, performance is a multifaceted phenomenon that touches all aspects of social life. It is particularly relevant to the global media-scape articulated by anthropologist Arjun Appadurai in which many forms of media flow across national borders.71 Examples of the global media-scape include American teenagers watching Bollywood movies produced in India, a Brazilian telenovela (soap opera) shown in Mozambique, and a Prague newspaper sent to family members living and working in Saudi Arabia. Globalization also helps explain why some performance genres that once were highly localized traditions, such as tango (originally from Argentina) and samba (originally from Brazil), are now internationally recognized, practiced, and celebrated.

In our modern globalized society, many performance genres have come unmoored from their cultural origins. It is one thing to consume such performances as spectators, but it is another to participate in these performance communities, leading to questions of authenticity and appropriation. For example, is it acceptable for a middle-class white American woman to perform an art like capoeira (see the preceding case study) that was traditionally associated with poor Afro-Brazilian men? Some in Afro-Brazilian communities view it as acceptable and embrace those willing to dedicate themselves to the art. Others are reluctant to adopt an inclusive philosophy, arguing that Afro-Brazilians endured years of suffering in service of preserving their art and therefore deserve to retain control of its future. Similar debates surround other performance genres with strong connections to ethnicity, such as jazz, blues, hip-hop, and rap.

International interest in local forms of performance also raises questions about intellectual property. For example, the Mbuti people of central Africa’s forests believe that song is the appropriate medium for communicating with the forest and alerting it to their needs.72 Song is also pleasurable for the Mbuti and associated with social harmony.73 Thus, song in general and the hindewhu, a hoot-like sound made with an indigenous musical instrument, in particular play important roles in the worldview of the Mbuti and related groups. Recently, their music has been transported out of the forest and into the mainstream, and anthropologist and ethnomusicologist Steven Feld has traced use of the hindewhu to songs by Madonna (Sanctuary) and Herbie Hancock (Watermelon Man).74 Hancock apparently developed his song after hearing the hindewhu on an ethnomusicology recording released in 1966. When asked about the appropriateness of using this signature sound out of context and without permission, Hancock said “this is a brothers kind of thing,” implying that their shared African ancestry allowed him to coopt the Mbuti’s musical heritage.75 The central issue is not whether Hancock’s claim to shared heritage justifies his use of the hindewhu but whether people like the Mbuti have a right to control the use, reproduction, and alteration of their cultural performances. As world beat music grows in popularity and many indigenous peoples become savvier about protecting their cultural and intellectual rights, these questions will be more pressing.

Another effect of globalization is the rise to new types of performances. For example, many performances are specifically staged for media consumption and distribution, such as photo opportunities arranged by politicians and celebrities. Similarly, some performances no longer exist outside of a media-related state, such as online-only campaigns, protests, and movements. Focusing on the performances regardless of the cultural configuration in which they occur allows anthropologists to more fully understand these emerging forms and practices. All of culture changes constantly, at different rates and in various ways, and performance is no exception. Amid ongoing expansion of modern technologies, the significance of performance in globalized contexts is central to anthropology’s ultimate commitment to holistic understanding. As a technology or format becomes commonplace, new options arise as people construct profiles and albums, build social networks across online and mobile applications, and make, post, and share videos. These sites of personal presentation and social action are all sites of cultural performance and performances of culture.

CONCLUSION

The band takes a final bow and exits the stage. The lights come up and people begin streaming out of the auditorium. One performance ends but a multitude of others continues. The security guard continues to present a picture of authority, ensuring orderly behavior. A woman smiles as a man makes a show of opening the car door for her. And Jayden promises to call Dakota sometime next week.

This chapter has highlighted the many different kinds of performance that interest anthropologists. Under anthropology’s holistic approach, performance connects to topics from many earlier chapters, including rituals (Religion chapter) and gender (Gender and Sexuality chapter). As we have shown, explicit attention to various performance-based frameworks allows anthropologists to identify the learned and shared patterns of ideas and behaviors that constitute human experience and living. We started the chapter by noting that performance can be many things at once, making it important to so much of human cultural experiences. Cultural performances are the events that most readily fit the Western notion of a performance: clearly defined moments of heightened salience of some feature of a culture’s values or social structure. These performances call attention to issues that might otherwise go unnoticed by audience members and consequently can inspire or instigate action. Such performances also can preserve aspects of a culture or facilitate cultural revitalization. Performing culture, on the other hand, refers to the many diverse ways in which individuals both reflect and create cultural norms through daily activities, interactions, and behaviors. Culture does not, indeed cannot, exist simply as an abstract concept. Rather, it arises from the patterned flows of people’s lives—their ongoing performances.

Anthropologists who study performance are interested in many of the same topics as other anthropologists, including: gender, religion, rituals, social norms, and conflict. Performance provides an alternative perspective for exploring and understanding those issues. Rather than studying rituals from a structural-functional perspective, for example, anthropologists can focus on performance and thereby better identify and understand theatrical structure and how communities use performance to accomplish the work of rituals. In short, performance anthropologists are interested not only in the products of social life but in the processes underlying it.

(P.S. Good luck Jayden and Dakota!)

Discussion Questions

- What is the difference between studying something that is performance and studying something as a performance? Why is this distinction important?

- What is the role of performance in reflecting social order and values on the one hand and challenging these and leading to social change on the other? Provide examples of each.

- Explain the relationship between performance and cultural constructions of gender.

- How are descriptive and performative utterances different from each other, and what role to each play in verbal performance?

- What roles do performances play in everyday life, especially as these relate to hegemonic discourses?

GLOSSARY

Agency: An individual’s ability to make independent choices and act upon his/her will.

Community of practice: a group of people who engaged in a shared activity or vocation, such as dance or medicine.

Cultural Performance: A performance such as a concert or a play.

Discourse: Widely circulated knowledge within a community.

Hegemonic discourses: Situations in which thoughts and actions are dictated by those in authority.

Hegemony: Power so pervasive that it is rarely acknowledged or even recognized, yet informs everyday actions.

Performativity: Words or actions that cause something to happen.

Performing culture: Everyday words and actions that reflect cultural ideas and can be studied by anthropologists as a means of understanding a culture.

Personal front: Aspects of one’s clothing, physical characteristics, comportment, and facial expressions that communicate an impression to others.

Polysemy: Settings, situations, and symbols that convey multiple meanings.

Presentation of self: The management of the impressions others have of us.

Reflexivity: Awareness of how one’s own position and perspective impact what is observed and how it is evaluated.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Dr. Lauren Miller Griffith is an assistant professor of anthropology at Texas Tech University. Her research agenda focuses on the intersections of performance, tourism, and education in Brazil, Belize, and the USA. Specifically, she focuses on the Afro-Brazilian martial art capoeira and how non-Brazilian practitioners use travel to Brazil, the art’s homeland, to increase their legitimacy within this genre. Dr. Griffith’s current interests include the links between tourism, cultural heritage, and sustainability in Belize. She is particularly interested in how indigenous communities decide whether or not to participate in the growing tourism industry and the long-term effects of these decisions.

Dr. Jonathan S. Marion is an associate professor in the Department of Anthropology and a member of the Gender Studies Steering Committee at the University of Arkansas, and the author of Ballroom: Culture and Costume in Competitive Dance (2008), Visual Research: A Concise Introduction to Thinking Visually (2013, with Jerome Crowder), and Ballroom Dance and Glamour (2014). Currently the President of the Society for Humanistic Anthropology, and a Past-president of the Society of Visual Anthropology, Dr. Marion’s ongoing research explores the interrelationships between performance, embodiment, gender, and identity, as well as issues of visual research ethics, theory, and methodology.

NOTES

1. Richard Bauman and Pamela Ritch, “Informing Performance: Producing the Coloquio in Tierra Blanca,” Oral Tradition 9:2 (1994): 255.

2. David M. Guss, The Festive State: Race, Ethnicity, and Nationalism as Cultural Performance (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000), 9.

3. Milton Singer, “The Great Tradition in a Metropolitan Center: Madras,” Journal of American Folklore (1958): 347–388.

4. Singer, “The Great Tradition in a Metropolitan Center,” 351.

5. See Anya Peterson Royce, Anthropology of the Performing Arts: Artistry, Virtuosity, and Interpretation in Cross-Cultural Perspective (Walnut Creek, Altamira Press, 2004).

6. Victor Turner, The Anthropology of Performance (New York: Paj Publications, 1987).

7. Richard Schechner, Between Theater and Anthropology (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011).

8. Richard Bauman, Verbal Art as Performance (Long Grove: Waveland Press, 1984).

9. Turner, Anthropology of Performance, 23.

10. Laura A. Lewis, Chocolate and Corn Flour: History, Race, and Place in the Making of “Black” Mexico (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012).

11. Jay Ruby, Picturing Culture: Explorations of Film and Anthropology (Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2000): 240.

12. Erving Goffman, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (New York, Anchor Books, 1959).

13. Goffman, Presentation of Self.

14. Ibid,, 24.

15. Ibid.

16. Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (New York: Routledge, 1990); Judith Butler, Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of “Sex” (New York: Routledge, 1993).

17. Marcel Mauss, “Techniques of the Body” Economy and Society 2:1 (1973): 70–89.

18. Iris Marion Young, “Throwing Like a Girl: A Phenomenology of Feminine Body Comportment Motility and Spatiality” Human Studies 3:2 (1980): 137–156.

19. Sports Illustrated August 25 (2014), Cover.

20. Several authors have discussed the relationship between femininity and sport. On bodybuilding, see Anne Bolin, “Muscularity and Femininity: Women Bodybuilders and Women’s Bodies in Culturo-Historical Context,” in Fitness as Cultural Phenomenon, ed. Karina A. E. Volkwein (New York: Waxmann Münster, 1998). On figure skating, see Abigail M. Feder-Kane, “A Radiant Smile from the Lovely Lady,” in Reading Sport: Critical Essays on Power and Presentation, ed. Susan Birell and Mary G. McDonald (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2000). On ballroom, see Jonathan S. Marion, Ballroom: Culture and Costume in Competitive Dance (Oxford: Berg, 2008) and Ballroom Dance and Glamour (London: Bloomsbury, 2014). See also Lisa Disch and Mary Jo Kane, “When a Looker Is Really a Bitch: Lisa Olson, Sport, and the Heterosexual Matrix,” in Reading Sport: Critical Essays on Power and Presentation, ed. Susan Birell and Mary G. McDonald (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2000).

21. Margaret Mead, Sex and Temperament: In Three Primitive Societies (New York: Perennial, 2001[1935]).

22. Serena Nanda, Gender Diversity: Crosscultural Variation (Long Grove: Waveland, 2014).

23. Serena Nanda, Neither Man nor Woman: The Hijras of India (New York: Cengage, 1998).

24. Gilbert Herdt, The Sambia: Ritual, Sexuality, and Change in Papua New Guinea (New York: Cengage, 2005).

25. Don Kulik, Travesti: Sex, Gender, and Culture among Brazilian Transgendered Prostitutes (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998).

26. Heather A. Williams, “Miss Homegrown: The Performance of Food, Festival, and Femininity in Local Queen Pageants” (Ph.D. dissertation, Bowling Green State University, 2009), 3.

27. Ibid.

28. Robert H. Lavenda, “Minnesota Queen Pageants: Play, Fun, and Dead Seriousness in a Festive Mode” Journal of American Folklore (1988): 168–175.

29. Lavenda, “Queen Pageants,” 173.

30. Ibid.

31. Ibid., 171.

32. Ibid.

33. Turner, Anthropology of Performance.

34. Ibid., 74.

35. Ibid.

36. Ibid.

37. John Langshaw Austin, How to Do Things with Words (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1975).

38. Victor Turner and Edith Turner, “Performing Ethnography,” in The Anthropology of Performance, ed. Victor Turner (New York: PAJ Publications, 1987): 139–155.

39. Turner and Turner, “Performing Ethnography,” 142.

40. Ibid.

41. Schechner, Between Theatre and Anthropology.

42. Bauman and Ritch, “Informing Performance.”

43. Royce, Performing Arts.

44. Royce, Performing Arts, 44.