1.2: Brief history of a concept

- Page ID

- 39121

Since this discussion is intended for an international audience, it is important to know that the English word ‘culture’ does not refer to a universal concept. In fact, it may not even have direct counterparts in other European languages closely related to English. For example, even though the German word ‘Kultur’ and the Polish word ‘kultura’ resemble the English ‘culture’, there are important differences in meaning, and in more distant languages like Mandarin Chinese (wen hua), we might expect the differences to be even greater (Goddard, 2005). What this means is that if you are a speaker of Mandarin, you cannot rely on a simple translation of the term from a bilingual dictionary or Google Translate.

Scholars often begin their attempts to define culture by recounting the historical uses of the word. As Jahoda (2012) has noted, the word ‘culture’ comes originally from the Latin, colere, meaning “to till the ground” and so it has connections to agriculture. Now for historical reasons, a great many English words have Latin and French origins, so maybe it is not surprising that the word ‘culture’ was used centuries ago in English when talking about agricultural production, for example, ‘the culture of barley.’ Gardeners today still speak of ‘cultivating’ tomatoes or strawberries, although if they want to be more plain-spoken, they may just speak of ‘growing’ them. Moreover, biologists still use the word culture in a similar way when they speak of preparing ‘cultures of bacteria.’

Later, in 18th century France, says Jahoda, culture was thought to be “training or refinement of the mind or taste.” In everyday English, we still use the word in this sense. For instance, we might call someone a cultured person if he or she enjoys fine wine, or appreciates classical music, or visiting art museums. In other words, by the 18th century, plants were no longer the only things that could be cultured; people could be cultured as well.

Still later, culture came to be associated with “the qualities of an educated person.” On the other hand, an uneducated person might be referred to as “uncultured.” Indeed, throughout the 19th century, culture was thought of as “refinement through education.” For example, the English writer Matthew Arnold (1896, p. xi) referred to “acquainting ourselves with the best that has been known and said in the world.” If Arnold were still alive today, he would no doubt think that the person who reads Shakespeare is ‘cultured’ while the one who watches The Simpsons or Family Guy is not.

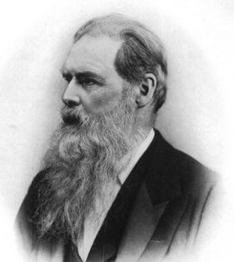

Near the end of the 19th century, the meaning of culture began to converge on the meaning that anthropologists would adopt in the 20th century. Sir Edward Tylor (1871, p. 1), for instance, wrote that:

Culture, or civilization … is that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, arts, morals, laws, customs and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society.

Notice that Tylor viewed culture as synonymous with civilization, which he claimed evolved in three stages.

CAUTION: Today we generally regard Tylor’s theory as mistaken, so please do not get too excited about the details that follow, but according to Tylor, the first stage of the evolution of culture was “savagery.” People who lived by hunting and gathering, Tylor claimed, exemplified this stage. The second stage, “barbarism,” Tylor said, described nomadic pastoralists, or people who lived by tending animals. The third stage, the civilized stage, described societies characterized by: urbanization, social stratification, specialization of labor, and centralization of political authority.

As a result, European observers of 19th century North America, noticing that many Indian tribes lived by hunting and gathering, thought of America as a “land of savagery” (Billington, 1985). Presumably, tribes that farmed and tended sheep were not savages but merely barbarians. But by this definition, many early English settlers in North America, as well as some populations still living in England, in so far as they lived mainly by farming and tending animals, could rightly be called barbarians. In fact, throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, many ‘cultured Europeans’ did regard Americans in the colonies as barbarians.

Now just to be clear, Europeans were not the only people with an inflated sense of their own superiority. In China, those living within the various imperial dynasties thought of people living far away from the center of the empire as barbarians. Moreover, they regarded everyone outside of China as barbarians. And this included the British.

But let’s return to Sir Edward Tylor and the elements that he identified as belonging to culture–knowledge, beliefs, arts, morals, laws, customs, and so on. This view of culture is certainly not far from 20th and 21st century views. But contemporary cultural scholars find Tylor mistaken in equating culture with civilization. Among the first scholars to drive this point home was Franz Boas.