2.7: Overviews of Living Primates (Haplorhines)

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 6059

As you no doubt recall, Haplorhini means "simple nose." The shared characteristics of tarsiers, New World monkeys, Old World monkeys, and apes include:

- relatively flattened faces (when compared to Strepsirhini)

- forward facing eyes

- postorbital enclosure (bony plate encloses back of eye socket)

- dry noses

- decreased reliance on sense of smell

- larger brains and body size (when compared to Strepsirhini)

- diastema (space between upper lateral incisor and upper canine tooth) except in humans

- increased gestation, maturation, and parental care

- more mutual grooming

.jpg?revision=1)

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Hamadryas Baboon (Papio hamadryas) at the Leipzig Zoo.

Tarsiers

The three genera of Tarsiidae;

- Carlito,

- Cephalopachus, and

- Tarsius,

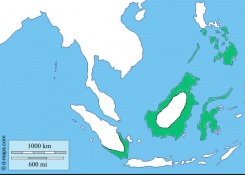

Eighteen species living among the islands of southeast Asia, including Borneo, Sumatra, and some of the Philippines. Tarsiers are arboreal vertical climbers and leapers and can be (not so easily) found in dense rainforest. They are occasionally found in non-forested habitats only if there are enough vertical surfaces for leaping and clinging. They rarely spend time on the ground. Tarsiers are sometimes called “living fossils” because of their close resemblance to fossil primates dated to about 40 million years ago. They are small primates, weighing about 4 ounces and roughly 5 inches in length, although with their tail, which may have a tuft of fur on the end, they almost double in length. Like some Strepsirhines, tarsiers have toilet claws and 36 teeth. They are also nocturnal or crepuscular and have huge eyes (just one of their eyes weighs as much as its brain!). In fact, under the traditional classification scheme, tarsiers were classified as prosimians; however, in the new classification system, tarsiers are Haplorhines because they do not have a wet rhinarium. Tarsiers can turn their heads 180 degrees and have the longest hind limb to forelimb proportion of any mammal. Because tarsiers are difficult to locate in the wild, it appears that reproduction is seasonal. Females give birth to a single offspring who weigh from 25 to 30% of the mother’s body weight. When infants are born they can immediately cling and climb. The mother is the primary caretaker, although dominant males and subadult females may help. Most tarsiers spend their waking hours alone hunting (they are the only true carnivorous primate), but sleep in small groups during the day. Tarsiers are territorial with male and females ranges overlapping.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) - Distribution of tarsiers. Original map from http://d-maps.com/pays.php?num_pay=67&lang=en modified to show distribution of tarsiers.

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) - Tarsier (Carlito syrichta), Bohol, Philippines.

New World Monkeys

There are several families of New World Monkeys (NWMs):

- Callitrichidae (i.e., marmosets and tamarins)

- Cebidae (i.e., squirrel monkeys and capuchins)

- Aotidae (i.e., night monkeys)

- Pitheciidae (e.g., sakis and titis) and

- Atelidae (i.e., howler monkeys and spider monkeys).

The 70+ species are found in Central and South America. All NWMs are arboreal although some will spend a little time on the ground. All are diurnal with the exception of the night monkey, which is nocturnal. All are quadrupeds, except for the spider monkey, which is a semi-brachiator. Some have prehensile tails, or “grasping” tails that serve as a fifth limb. Most, but not all, live in multi-male, multi-female groups. NWMs have flat noses with nostrils that are set far apart, wide open, and facing outwards.

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) - Distribution of New World Monkeys. Original blank map from http://d-maps.com/pays.php?num_pay=299&lang=en modified to show range of New World Monkeys.

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\) - White-eared Marmoset (notice the nostrils).

They have strong big toes that are “strongly opposable but their thumbs are imperfectly opposable and their fingers cannot grip well” (Natural History Collections…2001-2007). NWMs have twelve premolars unlike their counterparts in the Old World who have eight premolars. The territories of different groups within various NWM species frequently overlap and sometimes “friendships” develop between the different species (Blashfield 2014).

New World Monkeys: Callitrichidae

Callitrichids are small primates, including the smallest monkey, the pygmy marmoset, which weighs about 3.5 ounces when fully mature and averages between 5-6 inches in length, who live in Central and South America. They generally have little fur on their faces, but have tufts of fur on their heads. Some of the most colorful primates belong to the Callitrichids, e.g., golden lion tamarins (pictured above). Their tails are non-prehensile and are used for balance when moving quadrupedally through the trees. Unlike most other monkeys, they have claws instead of nails except on the big toe (also called a hallux), which does have a nail, allowing them to dig into the bark of trees. Callitrichids do not have a third molar and are primarily insectivorous, but eat gums, fruit, buds, leaves, flowers, lizards, frogs, and snails as well. They live in monogamous (e.g., golden lion tamarin) or polyandrous (e.g., saddle-back tamarin) family groups. Females normally give birth to twins with the exception of Goeldi’s monkey that has single births. All individuals in the group contribute to infant care. Genera of callitrichids include Callithrix, e.g., buffy-headed marmoset and black-tufted marmoset, Mico, e.g., silvery marmoset and Emilia’s marmoset, Cebuella, i.e., pygmy marmoset, and Saguinus, e.g., Emperor tamarin and cottontop tamarin, Callibella, i.e., dwarf marmoset, Callimico, i.e., Goeldi’s marmoset, Leontopithecus, e.g., golden lion tamarin and black lion tamarin.

Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\) - Golden lion tamarin family

_cockroach.jpg?revision=1)

Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\) - Common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus) eating a cockroach

New World Monkeys: Cebidae

There are three genera of cebids: 1) Cebus, e.g., Kaapori capuchin and white-headed capuchin, 2) Sapajus, e.g., black capuchin and tufted capuchin, and 3) Saimiri, e.g., bare-eared squirrel monkey and Central American squirrel monkey. They are relatively small primates, ranging in weight from around 2.5 pounds (adult male squirrel monkey) to 8.5 pounds (adult male brown capuchin). Unlike callitrichids, cebids have a prehensile tail and the third molar. They are arboreal omnivores, focusing on fruits and insects. Females give birth to one or two offspring and are responsible for the care of their young. They live in relatively large multi-male, multi-female groups with a dominant male. Cebids perform urine washing; they urinate on their hands and then rub them on their fur and feet in order to scent mark their territory. These quadrupeds can be found in Central and South America as well as Trinidad and Tobago, Caribbean islands off the coast of Venezuela.

Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\) - Bolivian-squirrel-monkey

Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\) - White-faced capuchin (Cebus capucinus) on Rio Frio, Costa Rica

New World Monkeys: Aotidae

Night monkeys, also called owl monkeys, are arboreal primates living in Panama and parts of South America. They are small, weighing up to just under three pounds and exhibit no sexual dimorphism. Like other nocturnal primates, night monkeys have large eyes. Their faces are rounded and marked with three dark brown or black lines—one on either side of their eyes and one in the middle of the forehead. Sometimes it appears as if night monkeys have no ears, but actually their small, rounded ears can be hidden by thick fur. Night monkeys are monogamous; mated pairs live with two or three offspring. Females usually have a single offspring, with both parents participating in infant care. Primarily frugivores, night monkeys will also eat leaves, flowers, insects, eggs, birds, spiders, and bats. Like cebids, night monkeys practice urine washing.

Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\) - Night monkey (Aotus zonalis)

New World Monkeys: Pitheciidae

The long-coated pithecids live in the various rainforest habitats in South America. These arboreal quadrupeds live in small groups. Titi monkey groups are centered on a monogamous pair while the sakis and uakaris live in multi-male, multi-female groups ranging from 10 individuals up to 100. Pithecids are territorial but generally use vocalizations instead of physical confrontation to defend their territory. All pithecids are frugivores; in fact, they are specialized frugivores called granivores who focus primarily on fruit seeds. Most pithecid females give birth to a single offspring. In general, males do not participate in infant care, although male sakis may groom their young and male titi monkeys provide the majority of care for their offspring. The four genera of pithecids are 1) Callcebus, e.g., titi monkeys, 2) Cacajao, e.g., uakaris, 3) Chiropotes, e.g., bearded sakis, and 4) Pithecia, e.g., sakis.

.jpg?revision=1)

Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\) - White-faced saki monkey

Figure \(\PageIndex{12}\) - Titi Monkey

Figure \(\PageIndex{13}\) - Uakari (Cacajao calvus)

New World Monkeys: Atelidae

The arboreal atelids are found in both Central and South America, although woolly monkeys are found only in the Amazon, muriquis are in Brazil’s southeaster rainforest, and yellow-tailed woolly monkeys are only in the cloud forests in the Peruvian Andes. The atelids range is size from the smaller spider monkey, weighing about 13-20 pounds, to the howler monkey, weighing up to 25 pounds. Atelids have prehensile tails with a hairless, tactile pad on the underside of the tip of the tail. This sticky pad helps the atelids hold on to things, especially tree limbs as they hang from their tails to eat. They are primarily frugivores, but will eat leaves, flowers, plant gums, and insects depending on the season. Atelids live in multi-male, multi-female groups, anywhere from two individuals up to one hundred (male howler monkeys are known to have “harems” of females). Males are philopatric; females leave their birth group. Atelids have ranges, but do not defend territories. When ranges overlap, conflict can occur. Females usually give birth to one offspring in the dry season and solely responsible for care of the young. While all of the atelids use vocalizations to communicate, howler monkeys are known for their distinctive calls, or roars, that can be heard (by humans) over a mile away.

Figure \(\PageIndex{14}\) - Howler monkey (Alouatta caraya)

Figure \(\PageIndex{15}\) - Geoffrey’s spider monkey

.jpg?revision=1)

Figure \(\PageIndex{16}\) - Woolly monkey (Lagothrix lagotricha)

References

- Allen CJ, Evans AV, McDade MC, Schlager N, Mertz LA, Harris MS, et al., editors. Marmosets, tamarins, and Goeldi’s monkey: Callitrichidae. In: Grzimek’s student animal life resource, Vol. 16: Mammals: Vol. 3. Detroit (MI): UXL; 2005. p. 496-508.

- Allen CJ, Evans AV, McDade MC, Schlager N, Mertz LA, Harris MS, et al., editors. Howler monkeys and spider monkeys: Atelidae. In: Grzimek’s student animal life resource, Vol. 16: Mammals: Vol. 3. Detroit (MI): UXL; 2005. p. 526-535.

- Allen CJ, Evans AV, McDade MC, Schlager N, Mertz LA, Harris MS, et al., editors. Night monkeys: Aotidae. In: Grzimek’s student animal life resource, Vol. 16: Mammals: Vol. 3. Detroit (MI): UXL; 2005. p. 509-515.

- Allen CJ, Evans AV, McDade MC, Schlager N, Mertz LA, Harris MS, et al., editors. Sakis, Titis, and Uakaris: Pitheciidae. In: Grzimek’s student animal life resource, Vol. 16: Mammals: Vol. 3. Detroit (MI): UXL; 2005. p. 516-525.

- Allen CJ, Evans AV, McDade MC, Schlager N, Mertz LA, Harris MS, et al., editors. Squirrel monkeys and capuchins: Cebidae. In: Grzimek’s student animal life resource, Vol. 16: Mammals: Vol. 3. Detroit (MI): UXL; 2005. p. 487-495.

- Blashfield JF. New World Monkeys. In: Lerner KL , Lerner BW, editors. The Gale Encyclopedia of Science, 5thedition, Vol. 6. Farmington Hills (MI): Gale; 2014. p. 3013-3018.

- Blashfield JF. Tarsiers. In: Lerner KL , Lerner BW, editors. The Gale Encyclopedia of Science, 5thedition, Vol. 8. Farmington Hills (MI): Gale; 2014. p. 4309-4310.

- Dewey T. 2007. Aotidae: night monkeys. Animal Diversity Web, University of Michigan Museum of Zoology [Internet] [cited 2015 Jun 28]. Available from: animaldiversity.org/accounts/Aotidae/

- Dewey T. 2007. Atelidae: howler and prehensile tailed monkeys. Animal Diversity Web, University of Michigan Museum of Zoology [Internet] [cited 2015 Jun 28]. Available from: animaldiversity.org/accounts/Atelidae/

- Dewey T. 2007. Pitheciidae: titi monkeys, sakis, and uakaris. Animal Diversity Web, University of Michigan Museum of Zoology [Internet] [cited 2015 Jun 28]. Available from: animaldiversity.org/accounts/Pitheciidae/

- Dewey T, Myers P. Tarsiidae: tarsiers. Animal Diversity Web, University of Michigan Museum of Zoology [Internet] [cited 2015 Jun 28]. Available from: animaldiversity.org/accounts/Tarsiidae/

- Jurmain R, Kilgore L, Trevathan W. 2013. Essentials of physical anthropology, 4th edition. Belmont (CA): Wadsworth, Cengage Learning.

- Larsen CS. 2008. Our origins: discovering physical anthropology. New York (NY): W.W Norton & Company, Inc.

- New World Monkeys [Internet]. c. 2001-2007. Edinburgh (Scotland): The Natural History Collections of the University of Edinburgh: [cited 2015 Jun 22]. Available from:http://www.nhc.ed.ac.uk/index.php?page=493.504.513

- Shefferly N. Callitrichinae: marmosets and tamarins. Animal Diversity Web, University of Michigan Museum of Zoology [Internet] [cited 2015 Jun 28]. Available from: animaldiversity.org/accounts/Callitrichinae/