1.5: Understanding Mindful Communication

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 66543

- Jason S. Wrench, Narissra M. Punyanunt-Carter & Katherine S. Thweatt

- SUNY New Paltz & SUNY Oswego via OpenSUNY

Learning Outcomes

- Define the term “mindfulness.”

- Describe the basic model of mindfulness.

- Discuss the five facets of mindfulness.

- Explain the relationship between mindfulness and interpersonal communication.

The words “mindful,” “mindfulness,” and “mindlessness” have received a lot of attention both within academic circles and outside of them. Many people hear the word “mindful” and picture a yogi sitting on a mountain peak in lotus position meditating while listening to the wind. And for some people, that form of mindfulness is perfectly fine, but it’s not necessarily beneficial for the rest of us. Instead, mindfulness has become a tool that can be used to improve all facets of an individual’s life. In this section, we’re going to explore what mindfulness is and develop an understanding of what we will call in this book “mindful communication.”

Defining Mindfulness

Several different definitions have appeared trying to explain what these terms mean. Let’s look at just a small handful of definitions that have been put forward for the term “mindfulness.”

- “[M]indfulness as a particular type of social practice that leads the practitioner to an ethically minded awareness, intentionally situated in the here and now.”15

- “[D]eliberate, open-minded awareness of moment-to-moment perceptible experience that ordinarily requires gradual refinement by means of systematic practice; is characterized by a nondiscursive, nonanalytic investigation of ongoing experience; is fundamentally sustained by such attitudes as kindness, tolerance, patience, and courage; and is markedly different from everyday modes of awareness.”16

- “[T]he process of drawing novel distinctions… The process of drawing novel distinctions can lead to a number of diverse consequences, including (1) a greater sensitivity to one’s environment, (2) more openness to new information, (3) the creation of new categories for structuring perception, and (4) enhanced awareness of multiple perspectives in problem solving.” 17

- “Mindfulness is a flexible state of mind in which we are actively engaged in the present, noticing new things and sensitive to context, with an open, nonjudgmental orientation to experience.” 18

- “[F]ocusing one’s attention in a nonjudgmental or accepting way on the experience occurring in the present moment [and] can be contrasted with states of mind in which attention is focused elsewhere, including preoccupation with memories, fantasies, plans, or worries, and behaving automatically without awareness of one’s actions.” 19

- “[T]he focus of a person’s attention is opened to admit whatever enters experience, while at the same time, a stance of kindly curiosity allows the person to investigate whatever appears, without falling prey to automatic judgment or reactivity.” 20

- “Paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally.” 21

- “Mindfulness is the practice of returning to being centered in this living moment right now and right here, being openly and kindly present to our own immediate mental, emotional, and bodily experiencing, and without judgment.” 22

- “[A]wareness of one’s internal states and surroundings. The concept has been applied to various therapeutic interventions—for example, mindfulness-based cognitive behavior therapy, mindfulnessbased stress reduction, and mindfulness meditation—to help people avoid destructive or automatic habits and responses by learning to observe their thoughts, emotions, and other present-moment experiences without judging or reacting to them.” 23

- “[A] multifaceted construct that includes paying attention to present-moment experiences, labeling them with words, acting with awareness, avoiding automatic pilot, and bringing an attitude of openness, acceptance, willingness, allowing, nonjudging, kindness, friendliness, and curiosity to all observed experiences.”24

What we generally see within these definitions of the term “mindfulness” is a spectrum of ideas ranging from more traditional Eastern perspectives on mindfulness (usually stemming out of Buddhism) to more Western perspectives on mindfulness arising out of the pioneering research conducted by Ellen Langer.25

Towards a Mindfulness Model

Shauna Shapiro and Linda Carlson take the notion of mindfulness a step farther and try to differentiate between mindful awareness and mindful practice:

(a) Mindful awareness, an abiding presence or awareness, a deep knowing that contributes to freedom of the mind (e.g. freedom from reflexive conditioning and delusion) and (b) mindful practice, the systematic practice of intentionally attending in an open, caring, and discerning way, which involves both knowing and shaping the mind. To capture both aspects we define the construct of mindfulness as “the awareness that arises through intentionally attending in an open, caring, and discerning way.”26

The importance of this perspective is that Shapiro and Carlson recognize that mindfulness is a cognitive, behavioral, and affective process. So, let’s look at each of these characteristics.

Mindful Awareness

First, we have the notion of mindful awareness. Most of mindful awareness is attending to what’s going on around you at a deeper level. Let’s start by thinking about awareness as a general concept. According to the American Psychological Association’s dictionary, awareness is “perception or knowledge of something.”27 Awareness involves recognizing or understanding an idea or phenomenon. For example, take a second and think about your breathing. Most of the time, we are not aware of our breathing because our body is designed to perform this activity for us unconsciously. We don’t have to remind ourselves to breathe in and out with every breath. If we did, we’d never be able to sleep or do anything else. However, if you take a second and focus on your breathing, you are consciously aware of your breathing. Most breathing exercises, whether for acting, meditation, public speaking, singing, etc., are designed to make you aware of your breath since we are not conscious of our breathing most of the time.

Mindful awareness takes being aware to a different level. Go back to our breathing example. Take a second and focus again on your breathing. Now ask yourself a few questions:

a. How do you physically feel while breathing? Why?

b. What are you thinking about while breathing?

c. What emotions do you experience while breathing?

The goal, then, of mindful awareness is to be consciously aware of your physical presence, cognitive processes, and emotional state while engaged in an activity. More importantly, it’s about not judging these; it’s simply about being aware and noticing.

Mindful Practice

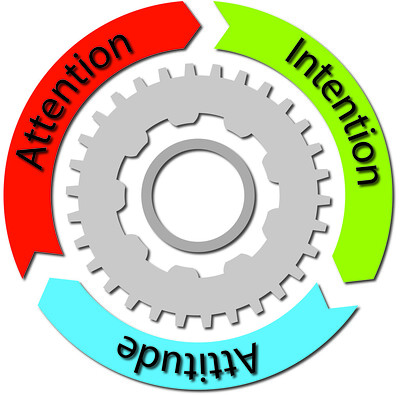

Mindful practice, as described by Shapiro and Carlson, is “the conscious development of skills such as greater ability to direct and sustain our attention, less reactivity, greater discernment and compassion, and enhanced capacity to disidentify from one’s concept of self.”28 To help further explore the concept of mindful practice, Shauna Shapiro, Linda Carlson, John Astin, and Benedict Freedman proposed a three-component model (Figure 1.5.1): attention, intention, and attitude.29

Attention

“Attention involves attending fully to the present moment instead of allowing ourselves to become preoccupied with the past or future.”30 Essentially, attention is being aware of what’s happening internally and externally moment-to-moment. By internally, we’re talking about what’s going on in your head. What are your thoughts and feelings? By externally, we’re referring to what’s going on in your physical environment. To be mindful, someone must be able to focus on the here and now. Unfortunately, humans aren’t very good at being attentive. Our minds tend to wander about 47% of the time.31 Some people say that humans suffer from “monkey mind,” or the tendency of our thoughts to swing from one idea to the next.32 As such, being mindful is partially being aware of when our minds start to shift to other ideas and then refocusing ourselves.

Intention

“Intention involves knowing why we are doing what we are doing: our ultimate aim, our vision, and our aspiration.”33 So the second step in mindful practice is knowing why you’re doing something. Let’s say that you’ve decided that you want to start exercising more. If you wanted to engage in a more mindful practice of exercise, the first step would be figuring out why you want to exercise and what your goals are. Do you want to exercise because you know you need to be healthier? Are you exercising because you’re worried about having a heart attack? Are you exercising because you want to get a bikini body before the summer? Again, the goal here is simple: be honest with ourselves about our intentions.

Attitude

“Attitude, or how we pay attention, enables us to stay open, kind, and curious.”34 Essentially, we can all bring different perspectives when we’re attending to something. For example, “attention can have a cold, critical quality, or an openhearted, curious, and compassionate quality.”35 As you can see, we can approach being mindful from different vantage points, so the “attitude with which you undertake the practice of paying attention and being in the present is crucial.”36 One of the facets of mindfulness is being open and nonjudging, so having that “cold, critical quality” is antithetical to being mindful. Instead, the goal of mindfulness must be one of openness and non-judgment.

So, what types of attitudes should one attempt to develop to be mindful? Daniel Siegel proposed the acronym COAL when thinking about our attitudes: curiosity, openness, acceptance, and love.37

- C stands for curiosity (inquiring without being judgmental).

- O stands for openness (having the freedom to experience what is occurring as simply the truth, without judgments).

- A stands for acceptance (taking as a given the reality of and the need to be precisely where you are).

- L stands for love (being kind, compassionate, and empathetic to others and to yourself).38

Jon Kabat-Zinn, on the other hand, recommends seven specific attitudes that are necessary for mindfulness:

- Nonjudging: observing without categorizing or evaluating.

- Patience: accepting and tolerating the fact that things happen in their own time.

- Beginner’s-Mind: seeing everything as if for the very first time.

- Trust: believing in ourselves, our experiences, and our feelings.

- Non-striving: being in the moment without specific goals.

- Acceptance: seeing things as they are without judgment.

- Letting Go: allowing things to be as they are and getting bogged down by things we cannot change.

Neither Siegel’s COAL nor Kabat-Zinn’s seven attitudes is an exhaustive list of attitudes that can be important to mindfulness. Still, they give you a representative idea of the types of attitudes that can impact mindfulness. Ultimately, “the attitude that we bring to the practice of mindfulness will to a large extent determine its long-term value. This is why consciously cultivating certain attitudes can be very helpful… Keeping particular attitudes in mind is actually part of the training itself.”39

Five Facets of Mindfulness

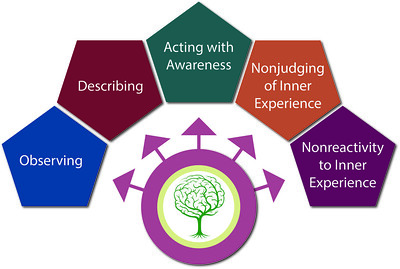

From a social scientific point-of-view, one of the most influential researchers in the field of mindfulness has been Ruth Baer. Baer’s most significant contribution to the field has been her Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire, which you can take on her website. Dr. Baer’s research concluded that there are five different facets of mindfulness: observing, describing, acting with awareness, nonjudging of inner experience, and nonreactivity to inner experience (Figure 1.5.2).40

Observing

The first facet of mindfulness is observing, or “noticing or attending to a variety of internal or external phenomena (e.g., bodily sensations, cognitions, emotions, sounds).”41 When one is engaged in mindfulness, one of the basic goals is to be aware of what is going on inside yourself and in the external environment. Admittedly, staying in the moment and observing can be difficult, because our minds are always trying to shift to new topics and ideas (again that darn monkey brain).

Describing

The second facet of mindfulness is describing, or “putting into words observations of inner experiences of perceptions, thoughts, feelings, sensations, and emotions.”42 The goal of describing is to stay in the moment by being detail focused on what is occurring. We should note that having a strong vocabulary does make describing what is occurring much easier.

Acting with Awareness

The third facet of mindfulness is acting with awareness, or “engaging fully in one’s present activity rather than functioning on automatic pilot.”43 When it comes to acting with awareness, it’s important to focus one’s attention purposefully. In our day-to-day lives, we often engage in behaviors without being consciously aware of what we are doing. For example, have you ever thought about your routine for showering? Most of us have a pretty specific ritual we use in the shower (the steps we engage in as we shower). Still, most of us do this on autopilot without really taking the time to realize how ritualized this behavior is.

Nonjudging of Inner Experience

The fourth facet of mindfulness is the nonjudging of inner experience, which involves being consciously aware of one’s thoughts, feelings, and attitudes without judging them. One of the hardest things for people when it comes to mindfulness is not judging themselves or their inner experiences. As humans, we are pretty judgmental and like to evaluate most things as positive or negative, good or bad, etc.… However, one of the goals of mindfulness is to be present and aware. As soon as you start judging your thoughts, feelings, and attitudes, you stop being present and become focused on your evaluations and not your experiences.

Nonreactivity to Inner Experience

The last facet of mindfulness is nonreactivity to inner experience “Nonreactivity is about becoming consciously aware of distressing thoughts, emotions, and mental images without automatically responding to them.”44 Nonreactivity to inner experience is related to the issue of not judging your inner experience, but the difference is in our reaction. Nonreactivity involves taking a step back and evaluating things from a more logical, dispassionate perspective. Often, we get so bogged down in our thoughts, emotions, and mental images that we end up preventing ourselves from engaging in life.

For example, one common phenomenon that plagues many people is impostor syndrome, or perceived intellectual phoniness.45 Some people, who are otherwise very smart and skilled, start to believe that they are frauds and are just minutes away from being found out. Imagine being a brilliant brain surgeon but always afraid someone’s going to figure out that you don’t know what you’re doing. Nonreactivity to our inner experience would involve realizing that we have these thoughts but not letting them influence our actual behaviors. Admittedly, nonreactivity to inner experience is easier described than done for many of us.

Mindfulness Activity

As a simple exercise to get you started in mindfulness, we want to spend 15 minutes coloring. Yep, you heard that right. We want you to color. Now, this may seem a bit of an odd request, but research has shown us that coloring is an excellent activity for increasing mindfulness, reducing anxiety/ stress, and increasing your mood.46,47,48,49Coloring also has direct effects on our physiology by reducing our heart rates and blood pressure.50 Coloring also helps college students reduce their test anxiety.51 For this exercise, we’ve created an interpersonal communication, mandala-inspired coloring page. According to Lawrence Shapiro, author of Mindful Coloring: A Simple and Fun Way to Reduce Stress in Your Life, here are the basic steps you should take to engage in mindful coloring:

As a simple exercise to get you started in mindfulness, we want to spend 15 minutes coloring. Yep, you heard that right. We want you to color. Now, this may seem a bit of an odd request, but research has shown us that coloring is an excellent activity for increasing mindfulness, reducing anxiety/ stress, and increasing your mood.46,47,48,49Coloring also has direct effects on our physiology by reducing our heart rates and blood pressure.50 Coloring also helps college students reduce their test anxiety.51 For this exercise, we’ve created an interpersonal communication, mandala-inspired coloring page. According to Lawrence Shapiro, author of Mindful Coloring: A Simple and Fun Way to Reduce Stress in Your Life, here are the basic steps you should take to engage in mindful coloring:

- Set aside 5 to 15 minutes to practice mindful coloring.

- Find a time and place where you will not be interrupted.

- Gather your materials to do your coloring and sit comfortably at a table. You may want to set a timer for 5 to 15 minutes. You should try and continue your mindful practice until the alarm goes off.

- Choose any design you like and begin coloring wherever you like.

- As you color, start paying attention to your breathing. You will probably find that your breathing is becoming slower and deeper, but you don’t have to try to relax. In fact, you don’t have to try and do anything. Just pay attention to the design, to your choice of colors, and to the process of coloring.52

After completing this simple exercise, answer the following questions:

- How did it feel to just focus on coloring?

- Did you find your mind wandering to other topics while coloring? If so, how did you refocus yourself?

- How hard would it be to have that same level of concentration when you’re talking with someone?

Interpersonal Communication and Mindfulness

For our purposes within this book, we want to look at issues related to mindful interpersonal communication that spans across these definitions. Although the idea of “mindfulness” and communication is not new,53,54 Judee Burgoon, Charles Berger, and Vincent Waldron were three of the first researchers to formulate a way of envisioning mindfulness and interpersonal communication.55 As with the trouble of defining mindfulness, perspectives on what mindful communication is differ as well. Let’s look at three fairly distinct definitions:

- “Communication that is planful, effortfully processed, creative, strategic, flexible, and/or reason-based (as opposed to emotion-based) would seem to qualify as mindful, whereas communication that is reactive, superficially processed, routine, rigid, and emotional would fall toward the mindless end of the continuum.” 56

- “Mindful communication including mindful speech and deep listening are important. But we must not overlook the role of compassion, wisdom, and critical thinking in communication. We must be able to empathize with others to see things from their perspective. We should not continue with our narrow prejudices so that we can start meaningful relationships with others. We can then come more easily to agreement and work together.”57

- “Mindful communication includes the practice of mindful presence and encompasses the attributes of a nonjudgmental approach to [our interactions], staying actively present in the moment, and being able to rapidly adapt to change in an interaction.”58

As you can see, these perspectives on mindful communication align nicely with the discussion we had in the previous section related to mindfulness. However, there is not a single approach to what is “mindful communication.” Each of these definitions can help us create an idea of what mindful communication is. For our purposes within this text, we plan on taking a broad view of mindful communication that encompasses both perspectives of secular mindfulness and non-secular mindfulness (primarily stemming out of the Buddhist tradition). As such, we define mindful communication as the process of interacting with others while engaging in mindful awareness and practice. Although more general than the definitions presented above, we believe that aligning our definition with mindful awareness and practice is beneficial because of Shapiro and Carlson’s existing mindfulness framework.59

However, we do want to raise one note about the possibility of mindful communication competence. From a communication perspective, it’s entirely possible to be mindful and not effective in one’s communication. Burgoon, Berger, and Waldron wrote, “without the requisite communication skills to monitor their actions and adapt their messages, without the breadth of repertoire that enables flexible, novel thought processes to translate into creative action, a more mindful state may not lead to more successful communication.” 60 As such, a marriage must be made between mindfulness and communication skills. This book aims to provide a perspective that enhances both mindfulness and interpersonal communication skills.

Key Takeaways

- The term “mindfulness” encompasses a range of different definitions from the strictly religious (primarily Buddhist in nature) to the strictly secular (primarily psychological in nature). Simply, there is not an agreed upon definition.

- Shauna Shapiro and Linda Carlson separate out mindful awareness from mindful practice. Mindful practice involves three specific behaviors: attention (being aware of what’s happening internally and externally moment-to-moment.), intention (being aware of why you are doing something), and attitude (being curious, open, and nonjudgmental).

- Ruth Baer identified the five facets of mindfulness. The five facets of mindfulness are (1) observing (being aware of what is going on inside yourself and in the external environment), (2) describing (being detail-focused on what is occurring while putting it into words), (3) acting with awareness (purposefully focusing one’s attention on the activity or interaction in which one is engaged), (4) nonjudging of inner experience (being consciously aware of one’s thoughts, feelings, and attitudes without judging them), and (5) nonreactivity to inner experience (taking a step back and evaluating things from a more logical, dispassionate perspective). Mindful communication is the process of interacting with others while engaging in mindful awareness and practice. So much of what we do when we interact with people today centers around our ability to be mindful, in the moment with others. As such, examining how to be more mindful in our communication with others is essential to competent communication.

Exercises

- If you haven’t already tried mindful coloring, please take this opportunity to try it out. Give yourself 10 to 15 minutes in a quiet space to just sit and focus on the coloring. Try not to let yourself get disturbed by other things in your environment. Just focus on being present with your colors and the coloring sheet.

- Want to try something a bit deeper in mindfulness? Consider starting simple meditation. Meditating is an important facet of mindfulness, and although most religious traditions have some form of meditation practice built into the religion, it is not specifically religious in nature. Even atheists can meditate. Try a simple meditation like:

- Seated Breath Meditation: This technique can help you:

- Enhance mental clarity

- Be fully present in the moment

- Understand your inner emotional state

- Feel grounded

- Seated Breath Meditation: This technique can help you:

Find a quiet place. Light a candle if you wish. Sit tall in your chair, feet on the floor, or sit comfortably on the floor. Align your spine, shoulders over hips, as if suspended from above. Hands can be in your lap or on your thighs, palms up, or press palms together at heart. Feel your posture as both rooted and energetic. Eyes can be closed or softly focused. Mouth is closed, tongue relaxed. Be sure you can breathe comfortably.

Center your awareness on your nostrils, where the air enters and leaves your body. Notice your breath. Begin counting your breaths, returning to one every time a thought intrudes. When thoughts come in, notice them, then let them go. Bring yourself back to your physical body, to the breath coming in and out.

Source: Thousand Waves Martial Arts & Self Defense Center (thousandwaves.org)

- Want to try some longer meditation practices? The Free Mindfulness Project has links to a number of mindfulness audio files.