10.1: Friendship Relationships

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 66602

- Jason S. Wrench, Narissra M. Punyanunt-Carter & Katherine S. Thweatt

- SUNY New Paltz & SUNY Oswego via OpenSUNY

Learning Outcomes

- Evaluate Rawlins’ friendship characteristics.

- Analyze the importance of communication in the formation of friendships.

- Appraise Rawlins’ dialectical approach to friendships.

In a 2017 book on the psychology of friendship, Michael Monsour asked the different chapter authors if they planned on defining the term “friendship” within their various chapters.12 Monsour found that the majority of the authors planned on not defining the term “friendship,” but instead planned on identifying characteristics of the term “friendship.” We point this out because defining “friend” and “friendship” isn’t an easy thing to do. We all probably see our friendships as different or unique, which is one of the reasons why defining the terms is so hard. For our purposes in this chapter, we’re going to go along with the majority of friendship scholars and not provide a strict definition for the term.

Friendship Characteristics

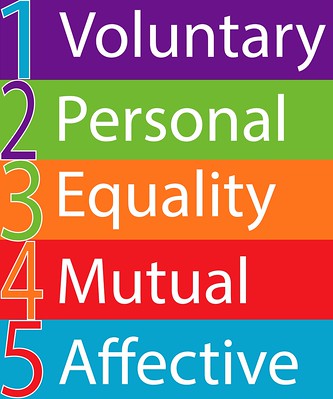

William K. Rawlins, a communication scholar and one of the most influential figures in the study of friendship, argues that friendships have five essential characteristics that make them unique from other forms of interpersonal relationships: voluntary, personal, equality, involvement, and affect (Figure 1).13

All Friendships are Essentially Voluntary

There’s an old saying that goes, “You can’t choose your family, but you can choose your friends.” This saying affirms the basic idea that friendship relationships are voluntary. Friendships are based out of an individual’s free will to choose whom they want to initiate a friendship relationship with. We go through our lives constantly making decisions to engage in a friendship with one person and not engage in a friendship with another person. Each and every one of us has our reasons for friendships. For example, one of our coauthors originally established a friendship with a peer during graduate school because they were the two youngest people in the program. In this case, the friendship was initiated because of demographic homophily but continues almost 20 years later because they went on to establish a deeper, more meaningful relationship over time. Take a second and think about your friendships. Why did you decide to engage in those friendships? Of course, the opposite is also true. We meet some people and never end up in friendship with them. Sometimes it’s because you’re not interested or the other person isn’t interested (voluntariness works both ways). We also choose to end some friendships when they are unhealthy or no longer serve a specific purpose within our lives.

Friendships are Personal Relationships that are Negotiated Between Two Individuals

The second quality of friendships is that they are personal relationships negotiated between two individuals. In other words, we create our friendships with individuals and we negotiate what those relationships look like with that other individual. For example, let’s imagine you meet a new person named Kris. When you enter into a relationship with Kris, you negotiate what that relationship will look like with Kris. If Kris happens to be someone who is transgendered, you are still entering into a relationship with Kris and not everyone who is transgendered. Kris is not the ambassador for all things transgendered for us, but rather a unique individual we decide we want to be friends with. Hence, these are not group relationships; these are individualized, personal relationships that we establish with another person.

Friendships Have a Spirit of Equality

The next characteristic of friendships is a spirit of equality. Rawlins notes, “Although friendship may develop between individuals of different status, ability, attractiveness, or age, some facet of the relationship functions as a leveler. Friends tend to emphasize the personal attributes and styles of interaction that make them appear more or less equal to each other.”14 It’s important to note that we’re not saying a 50/50 split in everything is what makes a friendship equal. Friendships ebb and flow over time as friends’’ desires, needs, and interests change. For example, it’s perfectly possible for two people from very different social classes to be friends. In this case, the different social classes may put people at an imbalance when it comes to financial means, but this doesn’t mean that the two cannot still have a sense of equality within the relationship. Here are some ways to ensure that friendships maintain a spirit of equality:

- Both friend’s needs and desires are important, not just one person’s. 2. Both friends are curious about their friend’s personal life away from the friendship. 3. Both friends show affection in their own ways. 4. Both friends demonstrate effort and work in the relationship. 5. Both friends encourage the other’s goals and dreams. 6. Both friends are responsible for mutual happiness. 7. Both friends decide what activities to pursue and how to have fun. 8. Both friends are mutually engaged in conversations. 9. Both friends carry the other’s burdens. 10. Both friends desire for the relationship to continue and grow.

Friendships Have Mutual Involvement

The fourth characteristic of friendships is that they require mutual involvement. For friendships to work, both parties have to be mutually engaged in the relationship. This does not mean that friends have to talk on a daily, weekly, or even monthly basis for them to be effective. Many people establish long-term friendships with individuals they don’t get to see more than once a year or even once a decade. For example, my father has a group of friends from high school whom he meets up with once a year. His friends and their spouses pick a location, and they all meet up once a year for a week together. For the rest of the year, there are occasional emails and Facebook posts, but they don’t interact much outside of that. However, that once a year get together is enough to keep these long-term (70+ years at this point) friendships healthy and thriving.

The concept of “mutual involvement” can differ from one friendship pair to another. Different friendship pairs collaborate to create their sense of what it means to be a friend, their shared social reality of friendship. Rawlins states, “This interpersonal reality evolves out of and furthers mutual acceptance and support, trust and confidence, dependability and assistance, and discussion of thoughts and feelings.”15 One of the reasons why defining the term “friendship” is so difficult is because there are as many friendship realities as there are pairs of friends. Although we see common characteristics among them, it’s important to understand that these characteristics have many ways of being exhibited.

Friendships Have Affective Aspects

The final characteristic of friendships is the notion of affect. Affect refers to “any experience of feeling or emotion, ranging from suffering to elation, from the simplest to the most complex sensations of feeling, and from the most normal to the most pathological emotional reactions. Often described in terms of positive affect or negative affect, both mood and emotion are considered affective states.”16 Built into the voluntariness, personal, equal, and mutually involved nature of friendships is the inherent caring and concern that we establish within those friendships, the affective aspects. Some friends will go so far as to say that they love each other. Not in the eros or romantic sense of the term, but instead in the philia or affectionate sense of the term. People often use the term “platonic” love to describe the love that exists without physical attraction based on the writings of Plato. However, Aristotle, Plato’s student, believed that philia was an even more profound form of dispassionate, virtuous love that existed in the loyalty of friends void of any sexual connotations.

All friendships are going to have affective components, but not all friendships will exhibit or express affect in the same ways. Some friendships may exhibit no physical interaction at all, but this doesn’t mean they are not intimate emotionally, intellectually, or spiritually. Other friendships could be very physically affective, but have little depth to them in other ways. Every pair of friends determines what the affect will be like within that friendship pairing. However, both parties within the relationship must have their affect needs met. Hence, people often need to have conversations with friends about their needs for affection.

Communication and Friendship Formation

Now that we’ve explored the five basic characteristics of friendships, let’s switch gears and focus on communication and friendships. This entire chapter is about communication and friendships, but we’re going to explore two communication variables that impact the formation of friendships.

Communication Competence

Previously in this book, we talked about the notion of communication competence. For our purposes, we used the definition from John Wiemann, “the ability of an interactant to choose among available communicative behaviors in order that he [she/they] may successfully accomplish his [her/their] own interpersonal goals, while maintaining the face and line of his [her/their] fellow interactants within the constraints of the situation.”17 Not surprisingly, an individual’s communication competence impacts their friendships. Kenneth Rubin and Linda Rose-Krasnor took communication competence a step further and referred to social communicative competencies, “ability to achieve personal goals in social interaction while simultaneously maintaining positive relationships.”18 The most common place where we exhibit social competencies is within our friendships. Throughout our lifespans, we continue to develop our social communicative competencies through our continued interactions with others. However, individuals with lower levels of competency will have problems in their day-to-day communicative interactions. Analisa Arroyo and Chris Segrin tested this idea and found that individuals who reported having lower levels of communication competence were less satisfied in their friendships.19 Furthermore, individuals who rated a specific friend as having lower levels of communication competency reported lower levels of both friendship satisfaction and commitment. So right off the bat people with lower levels of communication competence are going to have problems in their communicative interactions with friends.

Communication Apprehension

Another variable of interest to communication scholars has been communication apprehension (CA). We know that peers tend to undervalue their quieter peers, generally seeing them as less credible and socially attractive.20 In a study examining friendships among college students, participants indicated how many people they would classify as “good friends.”21 Over one-third of the people with high levels of CA reported having no good friends at all. No students with low or average levels of CA reported having no good friends. Over half of high CA individuals also reported family members as being their good friends (e.g., siblings, parents/guardians, cousins). Less than 5% of individuals with low or average levels of CA mentioned relatives. Ultimately, we know it’s harder for people with higher levels of CA to establish relationships and keep those relationships growing. Furthermore, individuals with higher levels of CA are less satisfied with their communicative interactions with friends.22

As you can see, both communication competence and CA are important aspects of communication that impact the establishment of effective friendship relationships.

Dialectical Approaches to Friendships

Earlier in this book, we introduced you to the dialectical perspective for understanding interpersonal relationships. William K. Rawlins proposed a dialectical approach to friendships.23 The dialectics can be broken down into two distinct categories: contextual and interactional.

Contextual Dialectics

The first category of dialectics is contextual dialectics, which are dialectics that stem out of the cultural order where the friendship exists. If the friends in question live in the United States, then the prevailing social order in the United States will impact the friendship. However, if the friends are in Malaysia, then the Malaysian culture will be the prevailing social order that impacts the friendship. There are two different dialectics that Rawlins labeled as contextual: private/public and ideal/real.

Private/Public

The first friendship dialectic is the private/public dialectic. Let’s start by examining the public side of friendships in the United States. Sadly, these relationships aren’t given much credence in the public space. For example, there are no laws protecting friendships. Your friends can’t get health benefits from your job. Religious bodies don’t recognize your friendships. As you can see, we’re comparing friendships here to marriages, which do have religious and legal protections. In fact, in the legal system, the family often trumps friends unless there is a power of attorney or will.

As a significant historical side note, one of the biggest problems many gay and lesbian couples faced before marriage legalization was that their intimate partners were perceived as “friends” in the legal system. Family members could swoop in when Partner A died and evict and confiscate all of Partner A’s money and property unless there was an iron-clad will leaving the money and property to Partner B. From a legal perspective, marriage equality was very important in ensuring the rights of LGBTQIA individuals and their spouses.

On the opposite end of this dialectic, many friendship bonds are as strong if not stronger than familial or marital bonds. We voluntarily enter into friendships and create our sense of purpose and behaviors outside of any religious or legal context. In essence, these friendships are autonomous and outside of social strictures that define the lines of marital bonds. Instead of having a religious organization dictate the morality of a relationship, friendships ultimately develop a sense of morality that is based within the relationship itself.

Ideal/Real

From the moment we are born, we start being socialized into a wide range of relationships. Friendship is one of those relationships. We learn about friendships from our family, schools, media, peers, etc.… With each of these different sources of information, we develop an ideal of what friendship should be. However, friendships are not ideals; they are real, functioning relationships with plusses and minuses. This dialectic also impacts how we communicate and interact within the friendship itself. If our culture tells us that people must be reserved and respectful in private, then a simple act of laughing with another person could be an outward sign of friendship.

Interactional Dialectics

It’s important to understand that friendships change over time; along with how we interact within those friendships. For communication scholars, Rawlins interactional dialectics help us understand how communicative behavior happens within friendships.24 Rawlins noted four primary communicative dialectics for friendships: independence/dependence, affection/instrumentality, judgment/acceptance, and expressiveness/protectiveness.

Independence/Dependence

First and foremost, friendships are voluntary relationships that we choose. However, there is a constant pull between the desire to be an independent person and the willingness to depend on one’s friend. Let’s look at a quick example. A few weeks ago, you and one of your friends both mentioned that you wanted to see a new film getting released. A few weeks later, it’s a Friday afternoon and you’re done with class or work. The movie was released that day, so you go and watch a matinee. You decided to engage in behavior without thought of your friend. You acted independently. It’s also possible that you know your friend hates going to the movies, so engaging independent movie watching behavior is very much in line with the norms you’ve established within your friendship.

On the other side, we do depend on our friendships. You could have a friend that you do almost everything with, and it gets to the point that people see you as a duo and are shocked when both of you aren’t together. In these highly dependent friendships, individual behavior is probably very infrequent and more likely to be resented. Now, if you went to the movie alone in a highly dependent friendship, your friend may be upset or jealous because you didn’t wait to see it with her/him/them. You may have had the right to engage as an independent person, but a friend in a highly dependent friendship would see this as a violation. This story would cause even more friction within the friendship if you had promised your friend to see the movie with her/him/them. You would still be acting independently, but your friend would have a stronger foundation for being upset.

Ultimately, all friendships have to negotiate independence and dependence. As with the establishment of any friendship norm, the pair involved in the relationship needs to decide when it’s appropriate to be independent and when it is appropriate to be dependent. Maybe you need to check-in via text 20 times a day (pretty dependent) or talk on the phone once a year; in both cases, friendships are different and are in constant negotiation. It’s also important to note that a friendship that was once highly dependent can become highly independent and vice versa.

Affection/Instrumentality

The second interactional dialectic examines the intersection of affection as a reason for friendship versus instrumentality (the agency or means by which a person accomplishes her/his/their goals or objectives). As Rawlins noted, “This principle formulates the interpenetrated nature of caring for a friend as an end-in-itself and/or as a means to an end.”25 We already discussed the importance of affection in a friendship, but haven’t examined the issue of friendships and instrumentality. In friendships, the issue of instrumentality helps us understand the following question, “How do we use friendships to benefit ourselves?” Some people are uncomfortable with this question and find the idea of instrumentality very anti-friendship. Have you ever had a really bad day and all you needed was a hug from your best friend? Well, was that hug a sign of affection? Or did you use that friendship to get something you wanted/ needed (instrumentality)? We all do this to varying degrees within friendships. Maybe you don’t have a washer and dryer in your apartment, so you go to your best friend’s place to do laundry. In that situation, you are using your friend and that relationship to achieve a need that you have (wearing clean clothes).

The problem of instrumentality arises when one party feels that he/she/they are being used and taken for granted within the friendship itself or if one friend stops seeing these acts as voluntary and starts seeing them as obligatory. First, there are times when there is an imbalance in friendships, and one friend feels that they are being taken advantage of. Maybe the friend with the washer and dryer starts realizing that the only time their friend really reaches out to see if they’re available to hang out is when the friend needs to do laundry. Second, sometimes acts that were initially voluntary become seen as obligatory. In our example, maybe the friend who needs to wash their clothes starts to see what was once a nice, voluntary gesture as an obligation. If this happens, then the use of the washer and dryer becomes part of the rules of the friendship, which can change the dynamic of the relationship if the person with the washer and dryer isn’t happy about being used in this way.

Judgment/Acceptance

In our friendships, we expect that these relationships are going to enhance our self-esteem and make us feel accepted, cared for, and wanted. On the other hand, interpersonal relationships of all kinds are marked by judgmental messages. Ronald Liang argued that all interpersonal messages are inherently evaluative.26 So, how do we navigate the need to be accepted and the reality of being judged? A lot of this is involved in the negotiation of the friendship itself. Although we may not appreciate receiving criticism from others, Liang argues that criticism demonstrates to another person that we value them enough to judge.27 Now, can criticism become toxic? Yes. Maybe you’ve experienced a friend who criticized everything about you. Perhaps it got to the point where it felt that you needed to change pretty much everything about how you look, act, think, feel, and behave just to be “good enough” for your friend. If that’s the case, then that friend is clearly not criticizing you for your betterment but for her/his/their desires.

Expressiveness/Protectiveness

The final interactional dialectic is expressiveness/protectiveness. This dialectic questions the degree to which we want to express ourselves in our friendships while determining how much not to express to protect ourselves. As we discussed earlier in this book, social penetration theory starts with the basic idea that in our initial interactions with others we disclose a wide breadth about ourselves. Still, these are primarily surface level topics (e.g., what’s your major, what are your hobbies, where are you from). As time goes on, the number of topics we express decreases, but they become more personal (depth). In a friendship relationship, we have to navigate this breadth and depth in deciding what we express and what we protect.

Ultimately, this is an issue of vulnerability. When we open ourselves up to people and express those deeper parts of ourselves, there is an excellent likelihood that disclosure of these areas could cause greater harm to the individual self-disclosing if the information got out. For example, one of our coauthors had a friendship sour after our coauthor’s friend started talking to our coauthor’s parents about our coauthor’s sexual orientation. Our coauthor saw this as a massive violation of the confidentiality of what was self-disclosed in their friendship. This friend still speaks to our coauthor’s parents 20 years later, but our coauthor hasn’t spoken to this former friend since the trust was violated. All friendships are an exploration of what can be expressed and what needs to be protected. We all have some friends that we keep at arm’s length because we know we need to protect ourselves, since they tend towards being overly chatty or gossipy. At the same time, we have other friends who get to see the real us as we protect less and less of ourselves in those friendships. No one will ever completely know what’s going on in our heads, but deep friendships probably come the closest and also make us the most vulnerable.

Mindfulness Activity

In a 2018 survey of readers, the magazine mindful explored the qualities of good friendships, “(38%) was a friend’s propensity for understanding. Next was 29% for trustworthiness, followed by 13% for compassion. Another 15% of the vote was divided between positivity, generosity, sense of humor, and sharing similar interests and passions. Finally, 5% of respondents named other qualities, such as self-awareness and honesty.”28

For this activity, we want you to think about how you can become more mindful of your friendships. Here are three things you can do: be present, try something new, and practice compassion and kindness.29 Think about your friendships and answer the following questions:

- When you’re with your friends, are you truly present, or do you let distractions (e.g., your cell phone, personal problems) get in the way of your interactions?

- How often do you and your friends do new things, or are you stuck in a rut doing the same activities over and over again?

- When you’re with your friends, are you mindfully aware of your attention, intention, and attitude? If not, what can you do to refocus yourself to be more present?

Key Takeaways

- William K. Rawlins proposed five specific characteristics of friendships: voluntary (friendships are based on an individual’s free will), personal (we create our friendships with individuals negotiating what those relationships look like with that other individual), equality (friendships have a sense of balance that makes them appear equal), involvement (both parties have to be mutually engaged in the relationship), and affect (friendships involve emotional characteristics different from other types of relationships).

- Two important communication variables impact friendship formation: communication competence and CA. Individuals who have lower levels of communication competence have fewer opportunities to make friends and actually report lower overall satisfaction with their friendships. Individuals with CA are less likely to engage in interactions with others, so they have fewer opportunities to engage in friendships. Individuals with high levels of CA report having fewer friendships and are more likely to list a family member as her/his/their best friend.

- Rawlins’ dialectical approach to communication breaks friendship down into two large categories of dialectical tensions: contextual (private/public & ideal/real) and interactional(independence/dependence, affection/instrumentality, judgment/ acceptance, and expressiveness/protectiveness). These dialectical tensions provide friendship scholars a framework for understanding and discussing friendships.

Exercises

- Think about one of your current or past friendships. Examine that friendship using Rawlins’ five characteristics of friendships: voluntary, personal, equality, involvement, and affect.

- How has your communication competence or CA impacted your ability to develop friendships? Also, what advice would you give to someone who has low levels of communication competence or high levels of communication apprehension on how to form friendships?

- Think about one of your current or past friendships. Use Rawlins friendship dialectics to analyze this friendship (both contextual and interactional). After analyzing your friendship, what do these dialectical tensions tell you about the nature and quality of this friendship?