11.4: Marriage Relationships

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 66612

- Jason S. Wrench, Narissra M. Punyanunt-Carter & Katherine S. Thweatt

- SUNY New Paltz & SUNY Oswego via OpenSUNY

Learning Outcomes

- Describe the marriage relational dimensions discussed by Mary Anne Fitzpatrick.

- Explain the three different types of marital relationships described by Mary Anne Fitzpatrick.

- Discuss the application of Mary Anne Fitzpatrick’s relational dimensions to same-sex marriages.

Earlier in this text, we discussed dating and romantic relationships. For this chapter, we’re going to focus on marriages as a factor of family communication. To help us start our conversation of marriage, let’s look at some sage wisdom on the subject:

- “Marriage has no guarantees. If that’s what you’re looking for, go live with a car battery.” — Erma Bombeck

- “The trouble with some women is that they get all excited about nothing – and then marry him.” — Cher

- “I love being married. It’s so great to find that one special person you want to annoy for the rest of your life.” — Rita Rudner

- “By all means, marry. If you get a good wife, you’ll become happy; if you get a bad one, you’ll become a philosopher.” — Socrates

- “Marriage is an endless sleepover with your favorite weirdo.” — Unknown

- “Many people spend more time in planning the wedding than they do in planning the marriage.” — Zig Ziglar

Many writers, comedians, political figures, motivational speakers, and others have all written on the subject of marriage. For our purposes, we are going to examine marital types and the research associated with the Prepare/ENRICH studies.

Marital Types

One of the most important names in the area of family communication and marital research, in general, is a scholar named Mary Anne Fitzpatrick. Fitzpatrick was one of the first researchers in the field of communication to devote her career to the study of family communication. Most of her earliest research was in the area of marriage. The culmination of her earliest research on the subject was the publication of her important book, Between Husbands and Wives: Communication in Marriage in 1988.58 Although this book is over 30 years old now, the information she found and discussed in this book is still highly relevant to our understanding of marital relationships and marital communication.

Relational Dimensions

One of the earliest projects undertaken by Mary Anne Fitzpatrick was the creation of the Relational Dimensions Instrument. The creation of the measure started as part of her dissertation work in 1976,59 and was originally fleshed-out in a series of articles.60,61The RDI originally consisted of 200 items based on different ideas expressed in the literature about marriage at the time. Through her research, Fitzpatrick was able to fine-tune the measure to identify eight dimensions of marriage measured by 77 items. These eight dimensions fall into three larger categories: conventional versus nonconventional ideology, interdependence/autonomy, and conflict engagement/avoidance. The RDI can be seen in its entirety in a couple of different locations.62

Conventional vs. Nonconventional Ideology

The first large category of relational dimensions is what Fitzpatrick called ideologies. In this category, Fitzpatrick recognized two different ideologies traditionalism and uncertainty and change.

Ideology of Traditionalism

The first dimension is referred to as the ideology of traditionalism. Traditionalism is the idea that a couple has a very historically grounded and conservative perspective of marriage. For example, couples who see themselves as more traditional are more likely to believe that a wife should take her husband’s name when they get married. They are also more likely to think that the family should adhere to specific religious traditions and that children should be taught those traditions when growing up. Generally speaking, people with a traditional ideology are going to believe in a more rigid understanding of both the male and female roles within a marriage. As for specific communication issues associated with this ideology, there is a strong belief that families should look composed and keep their secrets to themselves. In other words, families should strive to keep up appearances and not talk about any of the issues going on within the family itself.

Ideology of Uncertainty and Change

The underlying idea of the ideology of uncertainty and change is basically the notion that people should be open to uncertainty. “Indeed, the ideal relationship, from this point-of-view, is one marked by the novel, the spontaneous, or the humorous. The individuals who score highly on this factor seem open to change. They believe that each should develop their potential, and that relationships should not constrain an individual in any way.”63

Interdependence vs. Autonomy

The second large category of relational dimensions is what Fitzpatrick called the struggle of interdependence versus autonomy. In every relationship, as people grow closer, there is the intertwining of people’s lives as they become more interdependent. At the same time, some people prefer a certain amount of individuality and autonomy outside of the relationship itself. “To figure out how connected spouses are, one has to look at the amount of sharing and companionship in the marriage as well as at the couple’s organization of time and space. The more interdependent the couple, the higher the level of companionship, the more time they spend together, and the more they organize their space to promote togetherness and interaction.”64

Sharing

The third dimension of marriage relationships is sharing. Sharing consists of two basic components. The first component involves discussing the affective or emotional health of each of the partners and the relationship while exhibiting nonverbal affective displays (e.g., touching holding hands in public). The second component expands across the other dimensions. “A high score on this factor would suggest an open sharing of love and caring, and the tendency to communicate a wide range and intensity of feelings. There is a sharing of both task and leisure activities, as well as a considerable degree of mutual empathy. Finally, these relational partners not only visit with friends but also seek new friends and experiences.”65

Autonomy

Autonomy is an individual’s independence in their own behaviors and thoughts. In a marriage relationship, autonomy can include having a “man cave” or a home office that is specified as “personal” space for one of the marriage partners. Some couples will even go on separate vacations from one another. In any relational dialectic, there is always the struggle between connectedness and autonomy. Different couples will place differing degrees of importance on autonomy.

Undifferentiated Space

The fifth dimension of marital relationships is undifferentiated space, or the idea that there are few constraints on physical spaces within the home. This undifferentiated space means that spouses do not see her/his/their ownership of personal belongings as much as they do ownership as a couple. Furthermore, individuals who score high in undifferentiated space are also more willing to open their homes to family and friends. On the other hand, individuals who have a low undifferentiated space generally see belongings in personal terms. “That’s my room.” “That’s my pen. “This is my mail.” Etc. These individuals are also more protective of their personal space from outsiders. When they do allow outsiders (e.g., family and friends) into the house, they want to forewarn the outsiders that this will happen and may limit access to parts of the house (e.g., office spaces, workshops, master bedrooms, master bathrooms).

Temporal Regularity

The next dimension, temporal regularity, examines strict a schedule couples stick to. Do they always get up at the same time? Do they always go to bed at the same time? Do they always eat their meals at the same time? Some marriages run like a well-scheduled train, while other marriages fluctuate temporally daily.

Conflict Engagement vs. Avoidance

The final broad category of relational dimensions examines how couples handle conflict. Some couples will actively avoid conflict, while others openly engage in conflict.

Conflict Avoidance

The seventh dimension of marital relationships is conflict avoidance. Couples who engage in conflict avoidance do not openly discuss any conflicts that occur within the marriage. Individuals who avoid conflict will even avoid expressing their true feelings about topics that could cause conflict. If, and when, they do get angry, they will hide that emotion from their spouse to avoid the conflict.

Assertiveness

The final relational dimension is assertiveness. When analyzing the items on the Relational Dimensions Instrument, Fitzpatrick noticed that two different patterns emerged. First, she saw a pattern of the use of persuasion or influence to get a partner to do specific things (e.g., watch a TV show, read a book/ magazine). At the same time, there is a sense of independence and the desire to stand up for oneself even front of friends. Ultimately, Fitzpatrick believed that “assertiveness” was the best term to capture both of these phenomena.66

The Relational Definitions

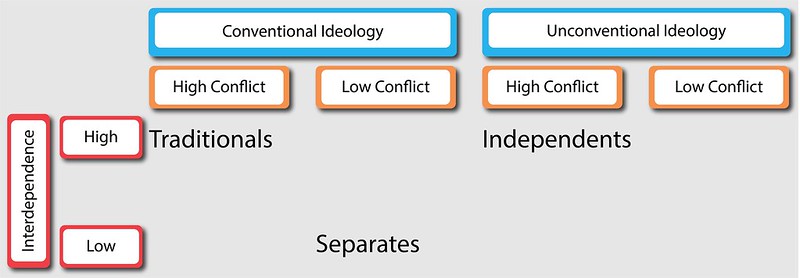

After creating the relational dimensions, Fitzpatrick then further broke this down into a marriage typology that included three specific marriage types: traditional, independents, and separates.67 Figure 11.4.1 illustrates how the three relational definitions were ultimately arrived at.

Traditionals

The first relational definition that Fitzpatrick arrived at was called traditionals. Traditionals are highly interdependent, have a conventional ideology, and high levels of conflict engagement. First, traditional lives are highly intertwined in both the use of space and time, so they are not likely to feel the need for autonomous space at home or an overabundance of “me time.” Instead, these couples like to be with each other and have a high degree of both sharing and companionship. These couples are more likely to have clear routines that they are happy with. These couples are traditionals also because they do have a conventional ideology. As such, they believe that a woman should take her husband’s name, keep family plans when made, children should be brought up knowing their cultural heritage, and infidelity is never excusable. Lastly, traditionals report openly engaging in conflict, but they do not consider themselves overly assertive in their conflict with each other. Of the three types, people in traditional marriages report the greatest levels of satisfaction.

Independents

The second relational definition that Fitzpatrick described was called independents. Independents have a high level of interdependence, an unconventional ideology, and high levels of conflict engagement. The real difference is their unconventional values in what a marriage is and how it functions. Independents, like their traditional counterparts, have high levels of interdependency within their marriages, so there is a high degree of both sharing and companionship reported by these individuals. However, independents tend to need more “me time” and autonomous space. Independents are also less likely to stick with a clear daily family schedule. To these individuals, marriage is something that compliments their way of life and not something that constrains it. Lastly, independents are also likely to openly engage in conflict and report moderate levels of assertiveness and do not avoid conflicts.

Separates

The final relational definition that Fitzpatrick described was called separates. Separates have low interdependence, have a conventional ideology, and low levels of conflict engagement. “Separates seem to hold two opposing ideological views on relationships at the same time. Although a separate is as conventional in marital and family issues as a traditional, they simultaneously support the values of independents and stress individual freedom over relational maintenance.”68 Ultimately, these couples tend to focus more on maintaining their individual identity than relational maintenance. Furthermore, these individuals are also likely to report avoiding conflict within the marriage. These individuals generally report the lowest levels of marriage satisfaction of the three.

Same-Sex Marriages

Up to this point, the majority of the information discussed in this section has been based on research explicitly conducted looking at heterosexual marriages. In one study, Fitzpatrick and her colleagues specifically set out to examine the three relational definitions and their pervasiveness among gay and lesbians.69 Ultimately, the researchers found that among “gay males, there are approximately the same proportion of traditionals, yet significantly fewer independents and more separates than in the random, heterosexual sample. For lesbians, there were significantly more traditionals, fewer independents, and fewer separates than in the random, heterosexual sample.”70 However, it’s important to note that this specific study was conducted just over 20 years before same-sex marriage became legal in the United States.

The reality is that little research exists thus far on long-term same-sex marriages. The legalization of same-sex marriages in July 2015 started a new period in the examination of same-sex relationships for family and family communication scholars alike.71 As a whole, LGBTQIA+ families, and marriages more specifically, is an under-researched topic. In a 2016 analysis of a decade of research on family and marriage in the most prominent journals on the subject, researchers found that only.02% of articles published during that time period directly related to LGBTQIA+ families.72 For scholars of interpersonal communication, the lack of literature is also problematic. In an analysis of the Journal of Family Communication, of the 300+ articles published in that journal since its inception in 2001, only nine articles have examined issues related to LGBTQIA+ families. This is an area that future scholars, maybe even you, will decide to study.

Key Takeaways

- Mary Anne Fitzpatrick started researching marriage relationships in the late 1970s. Her research found a number of specific relational dimensions that couples can take: conventional/nonconventional ideology, interdependence/autonomy, and conflict engagement/avoidance.

- Mary Anne Fitzpatrick described three specific relational definitions. First, traditional are couples who are highly interdependent, have a conventional ideology, and high levels of conflict engagement. Second, independents are couples who have a high level of interdependence, an unconventional ideology, and high levels of conflict engagement. Lastly, separates are couples who have low interdependence, a conventional ideology, and low levels of conflict engagement.

- Little research has examined how LGBTQIA+ couples interact in same-sex marriages. Research has shown that in a decade of studies about family and marriage, only.02% articles had to do with LGBTQIA+ families. In the field of communication, out of the 300+ studies published in the Journal of Family Communication, only nine of them involved LGBTQIA+ families. In the one study that examined Mary Anne Fitzpatrick’s relational dimensions among same-sex couples, the researchers found that gay males had approximately the same proportion of traditionals, yet significantly fewer independents and more separates than in the random, heterosexual sample. Conversely, among lesbian women there were significantly more traditionals, fewer independents, and fewer separates than in the random, heterosexual sample.

Exercises

- Think about a marital relationship where you know the couple fairly well. Examining the three relational dimensions (conventional/nonconventional ideology, interdependence/autonomy, and conflict engagement/avoidance), how would you categorize this couple? Why?

- Access a copy of Mary Anne Fitzpatrick’s Relational Dimensions Instrument (www.researchgate.net/publica...trumental_and_ expressive_domains_of_marital_communication), have a married couple that you know to complete the instrument separately. How similar were their responses? How different were their responses?

- Think about a marital relationship where you know the couple fairly well. Based on what you know about this couple, would you consider them traditional, independents, or separates? Why? Please be specific with your answer to demonstrate your understanding of these three marital types.