13.2: Leader-Follower Relationships

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 66624

- Jason S. Wrench, Narissra M. Punyanunt-Carter & Katherine S. Thweatt

- SUNY New Paltz & SUNY Oswego via OpenSUNY

Learning Outcomes

- Visual and explain Hersey and Blanchard’s situational-leadership theory, including the four types of leaders.

- Describe the concept of leader-member exchange theory and the three stages these relationships go through.

- Define Ira Chaleff’s concept of followership and describe the four different followership styles.

Perspectives on Leadership

When you hear the word “leader” what immediately comes to your mind? What about when you hear the word “follower?” The words “leader” and “follower” bring up all kinds of images (both good and bad) for most of us. We’ve all experienced times when we’ve followed a fantastic leader, and we’ve had times when we’ve worked for a less than an effective leader. At the same time, are we always the best followers? This section is going to examine prevailing theories related to leadership (situational-leadership theory and leader-member exchange theory), and then we’ll end the section discussing the concept of followership.

Hersey and Blanchard’s Situational-Leadership Theory

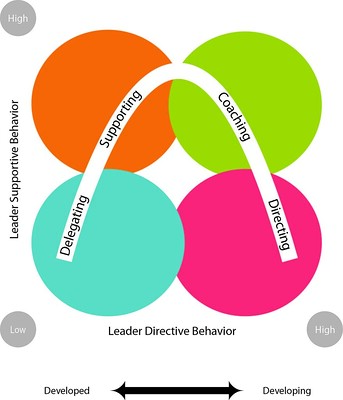

One of the most commonly discussed models of leadership is Paul Hersey and Kenneth Blanchard Situational Leadership Model (https://www.situational.com/). The model is divided into two dimensions: task (leader directive behavior) and relational (leader supportive behavior).14 Hersey and Blanchard’s situational leadership model starts with the basic idea that not all employees have the same needs. Some employees need a lot more hand-holding and guidance than others, and some employees need more relational contact than others. As such, Hersey and Blanchard define leadership along two continuums: supportive and directive. Supportive leadership behavior occurs when a leader is focused on providing relational support for their followers, whereas directive support involves overseeing the day-to-day tasks that a follower accomplishes. As a leader and a follower progress in their relationship, Hersey and Blanchard argue that the nature of their relationship often changes. Figure 13.2.1 contains the basic model proposed by Hersey and Blanchard and is broken into four leadership styles: directing, coaching, supporting, and delegating.15

Directing

Hersey and Blanchard’s first type of leader is the directing leader. Directing leaders set the basic roles an individual has and the tasks an individual needs to accomplish. After setting these roles and tasks, the leader then monitors and oversees their followers closely. From a communication perspective, these leaders usually to make decisions and then communicate them to their followers. There tends to be little to no dialogue about either roles or tasks.

Coaching

Hersey and Blanchard’s second type of leader is the coaching leader. Coaching leaders still set the basic roles and tasks that need to be accomplished by specific followers, but they allow for input from their followers. As such, the communication between coaching leaders and their followers tends to be more interactive instead of one-way. However, decisions about roles and tasks still ultimately belong to the leader

Supporting

Hersey and Blanchard’s third type of leader is the supporting leader. As a leader becomes more accustomed to a follower’s ability to accomplish tasks and take responsibility for those tasks, a leader may become more supportive. A supporting leader allows followers to make the day-to-day decisions related to getting tasks accomplished, but determining what tasks need to be accomplished is a mutually agreed upon decision. In this case, the leader facilitates rather than dictates the follower’s work.

Delegating

Hersey and Blanchard’s final type of leader is the delegating leader. The delegating leader and their follower are mutually involved in the basic decision making and problem-solving processes. Still, the ultimate control for accomplishing tasks is left up to the follower. Followers ultimately determine when they need a leader’s support and how much support is needed. As you can see from Figure 13.2, these relationships are ones that are considered highly developed and ultimately involve a level of trust on both sides of the leader-follower relationship.

Leader-Member Exchange Relationships

Fred Dansereau, George Graen, and William J. Haga proposed a different type of theory for understanding leadership.16 In leader-member exchange (LMX) theory, leaders have limited resources and can only take on high-quality relationships with a small number of followers.17 For this reason, some relationships are characterized as high-quality LMX relationships, but most are low-quality LMX relationships. High-quality LMX relationships are those “characterized by greater input in decisions, mutual support, informal influence, trust, and greater negotiating latitude.”18

In contrast, low-quality LMX relationships “are characterized by less support, more formal supervision, little or no involvement in decisions, and less trust and attention from the leader.”19 Ultimately, many positive outcomes happen for a follower who enters into a high LMX relationship with a leader. Before looking at some positive outcomes from high LMX relationships, we’re first going to examine the stages involved in the creation of these relationships.

Stages of LMX Relationships

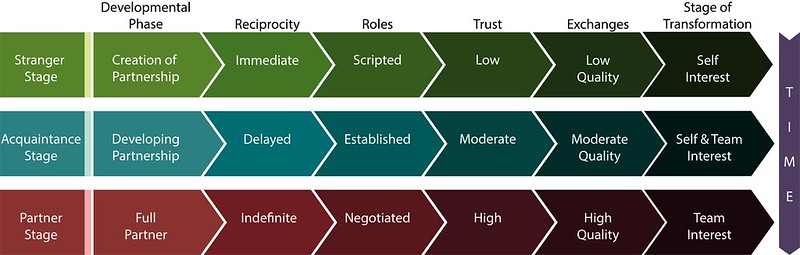

So, you may be wondering how LMX relationships are developed. George B. Graen and Mary Uhl-Bien created a three-stage model for the development of LMX relationships.20 Figure 13.2.2 represents the three different stages discussed by Graen and Uhl-Bien: stranger, acquaintance, and partner.

Stranger Stage

The first stage of LMX relationships is the stranger stage, and this is the beginning of the creation of an LMX relationship. Most LMX relationships never venture beyond the stranger stage because of the resources needed on both the side of the follower and the leader to progress further.

As you can see from Figure 13.2.2, the stranger stage is one where self-interest primarily guides the follower and the leader. These exchanges generally involve what Graen and Uhl-Bien call a “cash-andcarry” relationship. Cash-and-carry refers to the idea that some stores don’t utilize credit, so all purchases are made in cash, and customers carry their goods out of the store at the moment of purchase. In the stranger stage, interactions between a follower and leader follow this same process. The leader helps the follower and gets something immediately in return. Low levels of trust mark these relationships, and interactions tend to be carried out through scripted forms of communication within the normal hierarchical structure of the organization.

Acquaintance Stage

The second stage of high-quality LMX relationships is the acquaintance stage, when exchanges between a leader and follower become more normalized and aren’t necessarily based on a cash-and-carry system. According to Graen and Uhl-Bien, “Leaders and followers may begin to share greater information and resources, on both a personal and a work level. These exchanges are still limited, however, and constitute a ‘testing’ stage—with the equitable return of favors within a limited time perspective.”21 At this point, neither the leader nor the follower expects to get anything immediately in return within the exchange relationship. Instead, they start seeing this relationship as something that has the potential for long-term benefits for both sides. There also is a switch from purely personal self-interest to a combination of both self-interests and the interests of one’s team or organization.

Partner Stage

The final stage in the development of LMX relationships is the partner stage, or the stage where a follower stops being perceived as a follower and starts being perceived as an equal or colleague. A level of maturity marks these relationships. Even though the two people within the exchange relationship may still have titles of leader and follower, there is a sense of equality between the individuals within the relationship.

Outcomes of High LMX Relationships

Ultimately, high LMX relationships take time to develop, and most people will not enter into a high LMX relationship within their lifetime. These are special relationships but can have a wildly powerful impact on someone’s career and life. The following are some of the known outcomes of high LMX relationships when compared to those in low LMX relationships:

- Increased productivity (both quality and quantity).

- Increased job satisfaction.

- Decreased likelihood of quitting.

- Increased supervisor satisfaction.

- Increased organizational commitment.

- Increased satisfaction with the communication practices of the team and organization.

- Increased clarity about one’s role in the organization.

- Increased likelihood to go beyond their job duties to help other employees.

- Higher levels of success in their careers.

- Increased likelihood of providing honest feedback.

- Increased motivation at work.

- Higher levels of influence within their organization.

- Receive more desirable work assignments.

- Higher levels of attention and support from organizational leaders.

- Increased organizational participation. 22, 23, 24, 25

Research Spotlight

In a 2019 article, Leah Omilion-Hodges, Scott Shank, and Christine Packard wanted to find out what young adults want in a manager. To start, the researchers orally interviewed 22 undergraduate students whose mean age was 22. They asked the students about the general desires they have for managers, which included questions about general management style and communication (frequency and quality). Previous research by Omilion-Hodges and Christine Sugg had determined five management archetypes, which were reaffirmed in the current study:26

- Mentor: An empathetic advocate, professional, and personal guide.

- Manager: A proxy for organizational leadership who takes a transactional approach to leader-follower relationships.

- Teacher: Seen as a traditional educator who provides role testing episodes, clear feedback, and opportunities for redemption and growth.

- Friend: Although in a managerial position, perceived as an informed and approachable peer.

- Gatekeeper: A high-status actor who is positioned to either advocate for or against an employee. 27

a. In the current set of focus group interviews, the researchers focused more on the communicative and relational behaviors students wanted out of managers:

b. Mentor: Role model, leader by example, advocate, life coach, and someone who makes and leaves an impact.

c. Manager: Is the nuts and bolts of a functional organization, lacks a personal relationship with followers, monitors and delegates tasks, maintains the establishment, is structured and organized, sticks to the plan, follows rules and regulations, is strictly business, observes hierarchy and protocol, and is proficient in their day-to-day task accomplishment.

d. Teacher: Provides learning opportunities; supportive; dedicated to growth of the organization, delegates information, provides necessary resources, explicit directions, feedback, and one-on-one instruction.

e. Friend: Has a well-developed relationship with followers outside of work, is empathetic; supports followers in all areas of their lives including identity development, is seen as similar by followers, values employees as whole people (not just as workers), relationally focused.

f. Gatekeeper: Is removed from day-to-day operations, strategic, can help you advance or hold you back, abides rules and regulation, restricts information at their discretion, communicates only to influence, controls the successes and or failures of followers. 28

With the focus groups completed, the researchers used what they learned to create a 54-item measure of management archetypes, which they then tested with a sample of 153 participants. During the analysis process, the researchers lost the gatekeeper set of questions, but the other four management archetypes held firm. This study was confirmed in a third study using 249 students.

Omilion-Hodges, L. M., Shank, S. E., & Packard, C. M. (2019). What young adults want: A multistudy examination of vocational anticipatory socialization through the lens of students’ desired managerial communication behaviors. Management Communication Quarterly, 33(4), 512–547. doi. org/10.1177/0893318919851177

Followership

Although there is a great deal of leadership about the concepts of leadership, there isn’t as much about people who follow those leaders. Followership is “the act or condition under which an individual helps or supports a leader in the accomplishment of organizational goals.”29

Ira Chaleff (www. courageousfollower.net/) was one of the first researchers to examine the nature of followership in his book, The Courageous Follower. 30 Chaleff believes that followership is not something that happens naturally for a lot of people, so it is something that people must be willing to engage in. From this perspective, followership is not a passive behavior. Ultimately, followership can be broken down into two primary factors: the courage to support the leader and the courage to challenge the leader’s behavior and policies. Figure 13.2.3 represents the general breakdown of Chaleff’s four types of followers: resource, individualist, implementer, and partner. Before proceeding, you may want to watch the video Chaleff produced that uses tango to illustrate his basic ideas of followership (https:// youtu.be/Cswrnc1dggg).

Resource

The first follower style discussed by Chaleff is the resource. Resources will not challenge or support their leader. Chaleff argues that resources generally lack the intellect, imagination, and courage to do more than what is asked of them.

Individualist

The second followership style is the individualist. Individualists tend to do what they think is best in the organization, but not necessarily what they’ve been asked to do. It’s not that individualists are inherently bad followers; they have their perspectives on how things should get accomplished and are more likely to follow their perspectives than those of their leaders. Individualists provide little support for their leaders, and they are the first to speak out with new ideas that contradict their leader’s ideas.

Implementer

The third followership style is the implementer. Implementers are very important for organizations because they tend to do the bulk of the day-to-day work that needs to be accomplished. Implementers busy themselves performing tasks and getting things done, but they do not question or challenge their leaders.

Partner

The final type of followership is the partner. Partners have an inherent need to be seen as equal to their leaders with regard to both intellect and skill levels. Partners take responsibility for their own and their leader’s ideas and behaviors. Partners do support their leaders but have no problem challenging their leaders. When they do disagree with their leaders, partners point out specific concerns with their leader’s ideas and behaviors.

Key Takeaways

- Hersey and Blanchard’s situational-leadership theory can be seen in Figure 13.2. As part of this theory, Hersey and Blanchard noted four different types of leaders: directing, coaching, supporting, and delegating. Directing leaders set the basic roles an individual has and the tasks an individual needs to accomplish. Coaching leaders still set the basic roles and tasks that need to be accomplished by specific followers, but they allow for input from their followers. Supporting leader allows followers to make the day-to-day decisions related to getting tasks accomplished, but determining what tasks need to be accomplished is a mutually agreed upon decision. And a delegating leader is one where the follower and leader are mutually involved in the basic decision-making and problem-solving process, but the ultimate control for accomplishing tasks is left up to the follower.

- Leader-member exchange theory (LMX) explores how leaders enter into twoway relationships with followers through a series of exchange agreements enabling followers to grow or be held back. There are three stages of LMX relationships: stranger, acquaintance, and partner. The stranger stage is one where their selfinterests primarily guide the follower and the leader. In the acquaintance stage, exchanges between a leader and follower become more normalized and aren’t necessarily based on a cash-and-carry system. Finally, the partner stage is when a follower stops being perceived as a follower and starts being perceived as an equal or colleague.

- Followership is the act or condition under which an individual helps or supports a leader in the accomplishment of organizational goals. In Ira Chaleff’s concept of followership, he describes four different followership styles: resource, individualist, implementer, and partner. First, a resource is someone who will not support or challenge their leader. Second, an individualist is someone who engages in low levels of supervisory support but high levels of challenge for a leader. Third, implementers support their leaders but don’t challenge them, but they are known for doing the bulk of the day-to-day work. Lastly, partners are people who show both high levels of support and challenge for their leaders. Partners have an inherent need to be seen as equal to their leaders with regard to both intellect and skill levels.

Exercises

- Think back to one of your most recent leaders. If you were to compare their leadership style to Hersey and Blanchard’s situational-leadership theory, which of the four leadership styles did this leader use with you? Why do you think this leader used this specific style with you? Did this leader use different leadership styles with different followers?

- Why do you think high LMX relationships are so valuable to one’s career trajectory? Why do you think more followers or leaders go out of their ways to develop high LMX relationships?

- When thinking about your relationship with a recent leader, what type of follower were you according to Ira Chaleff’s concept of followership? Why?