10.3: Friendships in Different Contexts

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 66604

- Jason S. Wrench, Narissra M. Punyanunt-Carter & Katherine S. Thweatt

- SUNY New Paltz & SUNY Oswego via OpenSUNY

Learning Outcomes

- Differentiate between same-sex and opposite sex friendships.

- Evaluate J. Donald O’Meara five distinct challenges that opposite-sex relationships have.

- Define and explain the term “postmodern friendship.”

- Appraise the importance of cross-group friendships.

- Interpret the impact that mediated technologies have on friendships.

So far in this chapter, we’ve explored the foundational building blocks for understanding friendships. We’re now going to break friendships down by looking at them in several different contexts: gender and friendships, cross-group friendships, and mediated friendships.

Gender and Friendships

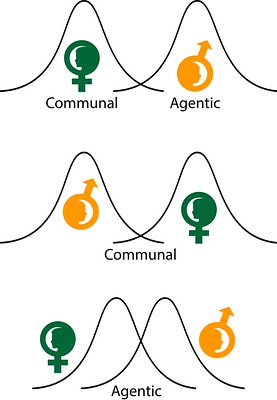

Based on a more traditional differentiation of both same and opposite sex friendships, early friendship research divided friendships into two categories communal and agentic. Communal friendships were marked by intimacy, personal/emotional expressiveness, amount of self-disclosure, quality of self-disclosure, confiding, and emotional supportiveness.43 Agentic friendships, on the other hand, were activity-centered. Figure 1 illustrates three curves associated with these concepts. The first one shows women being communal and men being agentic in their friendships, which was a common perspective on the nature of gender differences and friendships. In reality, research demonstrated that both males and females can have communal relationships even though women report notedly higher levels of communality in their friendships (second set of curves). As for agency, women and men were found to both have agentic friendships, and there was considerable overlap between the two groups here, with men being slightly more agentic (seen in the third set of curves).

.jpg?revision=1)

A great deal of research in friendship has focused on sex differences between males and females with regard to friendship. In this section, we’re going to start by looking at some of the research specifics to same-sex friendships and then opposite sex friendships. We’ll end this section discussing a different way of thinking about these types of relationships.

Same-Sex Friendships

For a lot of research, we use the term “same-sex” to refer to two individuals of the same biological sex as friends. Gerald Phillips and Julia Wood argue that there are four primary reasons females develop friendships with the same-sex: activities, personal support, problem-solving, and reciprocation.44 For female same-sex friendships, the first reason is activity. These are friendships that tend to develop around a specific activity: working out, church, social clubs, etc. For the most part, these friendships stay confined to the activity itself and provide a chance for conversation and noncommittal associations. The second reason is personal support. It’s this second category that many highlight when discussing the differences between female and male friendships. Personal support involves friendships where an individual has a personal confidant with whom they can share their deepest, darkest secrets, concerns, needs, and desires. These friendships are often highly stable friendships and tend to last for a long time. By nature, these friendships tend to be highly communal, which is why we generally discuss them as a key reason for female same-sex friendships. Third, all of us have areas where we’re skillful and lack skill. We often develop friendships with people who have skills that are complementary to our own. Consciously or subconsciously, we develop friendships with others out of a need to problem-solve in our daily lives. For example, an information technology specialist may become friends with an accountant. In their friendship, they provide complementary support: computer help and financial advice. Finally, females tend to view their friendships as highly reciprocal. They expect to get out of a friendship what they put into a friendship; it’s a mutual exchange. If a female feels her friend is not putting into a relationship the same amount of time and energy, she is less likely to keep sustaining that friendship.

As for male-male friendships, research shows us that they’re not drastically different, though their friendships may be framed differently. They still create friendships because of recreation, personal support, problem-solving, and reciprocation. And these relationships can be just as intimate as their female counterparts, but the relationships may look a bit more distinct. First, many male friendships are based around activities: church, work, hobbies, social clubs, etc. These friendships are less about having conversations and more about engaging in the activity at hand. These friendships are not going to be as communal as female friendships that develop around recreation. Often people mistake these male friendships as being less “intimate” because they do not disclose a lot of information, and there isn’t necessarily a lot of talk involved, but males do find these relationships perfectly fulfilling.

Phillips and Woods noted that men often view friendships in terms of teams; having allies and team members. In essence, they create their tight-knit circles of in and out-group members based on “team” status. Part of this team status involves performing favors for each other and siding with one another. It’s the whole “I’ve got your back” mentality. We should also note that males are more likely to be friends with those who are the most like them: similar majors, similar religion, similar rungs of the social hierarchy, similar socioeconomic status, similar attitudes, similar interests, etc. Research has even shown that males are more likely to have male friends who are equally physically attractive.45 One possible explanation for this phenomenon is that males are more likely to develop relationships based on social hierarchies. If attractive males are on a higher rung of a social hierarchy, then it’s not surprising that the matching effect occurs.46

Opposite Sex Friendships

“Friendship between a woman and a man? For many people, the idea is charming but improbable.”47 William Rawlins originally wrote this sentence in 1993 at the start of a chapter about the problems associated with opposite sex or opposite-sex friendships. What do you think? J. Donald O’Meara discusses five distinct challenges that opposite-sex relationships have: emotional bond, sexuality, inequality and power, public relationships, and opportunity structure.48,49

Emotional Bond

First and foremost, in Western society females and males are raised to see the opposite sex as potential romantic partners and not friends. One of the inherent problems with opposite-sex friendships is that one of the friends may misinterpret the friendship as romantic. From an emotional sense, the question that must be answered is how do friends develop a deep-emotional or even loving relationship with someone of the opposite sex. Unfortunately, females are more likely than males to think this is possible. William Rawlins did attempt to differentiate between five distinct love styles that could help distinguish the types of emotional bonds possible: friendship, Platonic love, friendship love, physical love, and romantic love.50 First, friendship is “a voluntary, mutual, personal and affectionate relationship devoid of expressed sexuality.”51 Second, Platonic love is an even deeper sense of intimacy and emotional commitment without sexual activity. Third, friendship love is the interplay between friendships and sexual relationships. It’s often characterized by the use of the terms “boyfriend” and “girlfriend” as distinguishing characteristics to denote paired romantic attachments. Fourth, physical love tends to involve high levels of sexual intimacy with love levels of relationship commitment. And finally, there’s romantic love, or a relationship marked by exclusivity with regards to emotional attachment and sexual activity. O’Meara correctly surmises that the challenge for opposite-sex friendships is finding that shared sense of love without one partner slipping into one of the other four categories of love because often the emotions associated with all five different types of love can be perceived similarly.

Sexuality

The obvious next step in the progression of issues related to opposite-sex friendships is sexuality. Sexual attraction is inherent in any opposite-sex friendship between heterosexual couples. Sexual attraction may not be something initial in a relationship. Still, it could develop further down the line and start to blur the lines between someone’s desire for friendship and a sexual relationship. In any opposite-sex friendship, there will always be a latent or manifested sexual attraction that is possible. Even if one of the parties involved in the friendship is completely unattracted to the other person, it doesn’t mean that the other friend isn’t sexually attracted. As such, like it or not, there will always be the potential for the issue of sexuality in opposite-sex friendships once people hit puberty. Now it’s perfectly possible that both parties within a friendship are mutually sexually attracted to each other and decide openly not to explore that path. You can find someone sexually attractive and not see them as a viable sexual or romantic partner. For example, maybe you both decide not to consider each other viable sexual or romantic partners because you’re already in healthy romantic relationships, or you may realize that your friendship is more important.

Inequality and Power

We live in a society where men and women are not treated equally. As such, a fact of inequality and power-imbalance, created by our society, will always exist between people in opposite-sex friendships. As such, males are in a better position to be in an exchange relationship. O’Meara argues that opposite-sex friendships should, therefore, strive to develop communal ones. However, there is also an imbalance that may exist when it comes to communal needs as well. Females are more likely to get their emotional needs through same-sex friendships. However, males are more likely to get their emotional needs met through opposite sex friendships. This dependence on the opposite sex for emotional needs and support places females in a subordinate position of needing to fulfill those needs.

Public Relationships

The next challenge for opposite-sex friendships involves the public side of friendships. The previous three challenges were all about the private inner workings of the friendship between a female and a male (internal side). This challenge is focused on public displays of opposite-sex friendships. First, it’s possible that others will see an opposite-sex friendship as a romantic relationship. Although not a horrible thing, this could give others the impression that a pair of friends are not available for romantic relationships. If one of the friends is seen on a date, other could get the impression that the friend is clearly cheating on their significant other. Second, it’s possible that others won’t believe the couple as “simply being friends.” This consistent devaluing of opposite-sex friendships and the favoring of opposite-sex romantic relationships in our society puts a lot of stress on opposite-sex friendships. Devaluing of friendships over romantic relationships can also be seen as a tool to delegitimize opposite-sex friendships. Third, it’s possible that others may question the sexual orientation of the individuals involved in the opposite-sex friendship. If a male is in a friendship relationship with a female, he may be labeled as gay or bisexual for not turning that opposite-sex friendship into a romantic one. The opposite is also true. Lastly, public opposite-sex friendships can cause problems for opposite-sex romantic partners. Although not always the case, it may be very difficult for one member of a romantic relationship to conceive that their partner is in a close friendship relationship with the opposite sex that is not romantic or sexual. For individuals who have never experienced these types of emotional connections, they may assume that it is impossible and that the opposite-sex friends are just “kidding themselves.” Another possible problem for romantic relationships is that the significant other becomes jealous of the opposite-sex friend because they believe that, as the significant other, they should be fulfilling any role an opposite-sex friend is.

Scouts are Changing with the Times

Just as a quick caveat, as of the publication of this book, the Girl Scouts of America is open to transgendered children on a case-by-case basis. However, Boy Scouts of America started accepting girls starting in 2017 and is now called Scouts BSA to show this change to policy.

Opportunity Structure

The final challenge described by O’Meara was not part of the original four but was described in a subsequent article.52 This question is primarily focused on how individuals find opportunities to develop opposite-sex friendships. A lot of our social lives are divided into females and males. Girls go to Girl Scouts and Boys to Boy Scouts. Girls play volleyball and softball while boys play football and baseball. Now, that’s not to say that there aren’t girls who play football or boys who play volleyball, but most of these sports are still highly sex-segregated. As such, when we’re growing up, we are more likely to spend social time with the same-sex. Ultimately, it’s not impossible for opposite-sex relationships to develop, but our society is not structured for these to happen naturally in many ways.

Postmodern Friendships

In the previous section, we looked at some of the basic issues of same-sex and opposite-sex friendships; however, a great deal of this line of thinking has been biased by heteronormative patterns of understanding.53 The noted absence of LGBTQIA+ individuals from a lot of the friendship literature is nothing new.54 We have needed newer theoretical lenses to help us break free of some of these historical understandings of friendship. “Growing out of poststructuralism, feminism, and gay and lesbian studies, queer theory has been favored by those scholars for whom the heteronormative aspects of everyday life are troubling, in how they condition and govern the possibilities for individuals to build meaningful identities and selves.”55 By taking a purely heteronormative stance at understanding friendships, friendship scholars built a field around basic assumptions about gender and the nature of gender.56

Friendship scholar Michael Monsour asked a group of friendship scholars about the definition of “friendship” and found there was little to no consensus. How then, Monsour argues, can researchers be clear in their attempts to define “gender” and “sex” when analyzing same-sex or opposite sex friendships?57 As part of his discussion questioning the nature of gender and sex and they have been used by friendship scholars, Monsour provided the following questions for us to consider:

- What does it mean to state that two individuals are in a same-sex or opposite sex friendship and/or that they are of the same or opposite sex from one another?

- What decision rules are invoked when deciding whether a particular friendship is one or the other?

- Why must the friendship be one or the other?

- If friendship scholars and researchers believe that all friendships are either same–sex or opposite-sex (and it appears that most do), at a minimum there should be agreement about what constitutes biological sex. What biological traits make a person a female or a male?

- Are they absolute?

- Are they universal?58

- As part of this discussion, Monsour provides an extensive list of areas of controversy related to the terms used for binary gender identity. • What about individuals who are intersexed?

- What about individuals with chromosomal differences outside of traditional XX and XY (e.g., X, Y, XYY, XXX, XXY)? Heck, there are even some XXmales and XYfemales who develop because of chromosomal structural anomalies SRY region on the Y chromosome?

- What about bisexual, gay, and lesbian people?

- What about people who are transgendered?

- What about people who are asexual?

Hopefully, you’re beginning to see that the concept of labeling “same-sex” and “opposite sex” friendships based on heterosexual cisgendered individuals who have 46-chromosomal pairs that are either XX or XY may not be the best or most complete way of understanding friendship.

We should also note that research in the field of communication has noted that an individual’s biological sex contributes to maybe 1% of the differences between “females” and “males.”59 So, why would we use the words “same” and “opposite” to differentiate friendship lines when there is more similarity between groups than not? As such, we agree with the definition and conceptualization of the term created by Mike Monsour and William Rawlins’ “postmodern friendships.”60 A postmodern friendship is one where the “participants co-construct the individual and dyadic realities within specific friendships. This co-construction involves negotiating and affirming (or not) identities and intersubjectively creating relational and personal realities through communication.”61 Ultimately, this perspective allows individuals to create their own friendship identities that may or may not be based on any sense of traditional gender identities.

Cross-Group Friendships

As we noted above, research has found that one of the biggest factors in friendship creation is the groups one belongs too (more so for males than females). In this section, we’re going to explore issues related to cross-group friendships. A cross-group friendship is a friendship that exists between two individuals who belong to two or more different cultural groups (e.g., ethnicity, race, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, nationality). “The phrase, ‘Some of my best friends are...’ is all too typically used by individuals wanting to demonstrate their liberal credentials. ‘Some of my best friends are ... gay.’ ‘Some of my best friends are ... Black.’ People say, ‘Some of my best friends are ...’ and then fill in the blank with whatever marginalized group which they care to exonerate themselves.”62 Often when we hear people make these “Some of my best friends are…” statements, we view them as seriously suspect and question the validity of these relationships as actual friendships. However, many people develop successful cross-group friendships.

It’s important to understand that our cultural identities can help us feel that we are part of the “in-group” or part of the “out-group” as well. Identity in our society is often highly intertwined with marginalization. As noted earlier, we also know that males are more likely to align themselves with others they perceive as similar. Females do this as well, but not to the same degree as males. In essence, most of us protect our group identities by associating with people we think are like us, so it’s not surprising that most of our friendships are with people who are demographically and ideologically similar to us. To a certain extent, we judge members of different out-groups based on our ethnocentric perceptions of behavior. For example, some people ask questions like, “Why does my Black friend talk about race so much?”; “Does my friend have to act ‘so’ gay when we’re in public?”; or “I like my friend, but does she always have to talk to me about her religion?”. In these three instances (race, sexual orientation, and religion), we see examples of judging someone’s communicative behavior based on their own in-group’s communicative behavioral norms. Especially for people who are marginalized, being marginalized is a part of who they are that cannot be separated from how they think and behave. Maybe a friend talks about race because they are part of a marginalized racial group, so this is their experience in life. “This is actually normal and understandable behavior on the part of these different groups. They are not the ones who make it the focus of their lives. Society—the rest of us—makes race or orientation or gender an issue for them—an issue that they cannot ignore, even if they wanted to. They have to face it every waking moment of their lives.”63 People who live their lives in marginalized groups see this marginalization as part of their daily life, and it’s intrinsically intertwined with their identity.

Many of us will have the opportunity to develop cross-group friendships throughout our lives. As our society becomes more diverse, so does the likelihood of developing cross-group friendships. In a large research project examining the outcomes associated with cross-group friendships, the researchers found two factors were the most important when it came to developing cross-group friendships: racism and exposure to cross-group friendships. First, individuals who are racist are less likely to engage in cross-group friendships.64 Second, actual exposure to cross-group friendships can lead to more intergroup contact and more positive attitudes towards members in those groups. Ultimately, successful cross-group friendships succeed or fail based on two primary factors: time and self-disclosure.65

First, successful cross-group friendships take time to develop, so don’t expect them to happen overnight. Furthermore, these relationships will take more time to develop as you navigate your cultural differences in addition to the terms of the friendship itself. It’s important that when we use the word “time” here, we are not only discussing both longitudinal time, but also the amount of time we spend with the other person. The more we interact with someone from another group, the stronger our friendship will become.

Second, successful cross-group friendships involve high amounts of self-disclosure. We must be open and honest with our thoughts and feelings. We need to discuss not only the surface level issues in our lives, but also have deeper, more meaningful disclosures about who we are as individuals and who we are as individuals because of our cultural groups. One of our coauthor’s best friend is from a different racial background. Our coauthors grew up in the Southern part of the United States, and our coauthor’s friend grew up in the inner-city area in Los Angeles. When they met, they had very different lived experiences related to both race and geographic differences. Their connection was almost instantaneous, but the friendship grew out of many long nights of conversations over many years.

Mediated Friendships

Probably nothing has more radically altered the meaning of the words “friend” and “friendship” than widespread use of social technology. Although the Internet has been around since 1969 and was consistently used for the exchange of messages through the 1990s, the public didn’t start to become more actively involved with the technology until it became cheap enough to use in one’s daily life. Before December 1996, using the “information superhighway” was limited to tech professionals, colleges and universities, the government, and hobbyists. The pricing model for Internet use had been similar to that of a telephone subscription. You paid a base rate that allowed you so many hours each month (usually 10) of connected Internet time, and then you paid an additional rate for each subsequent hour. People who were highly active on the Internet racked up enormous bills for their use. Of course, this all changed in December 1996 when America Online (AOL) decided to offer unlimited internet access to the world for $19.95 per month. This change in the pricing structure ultimately led to the first real wave of people jumping online because it was now economically feasible.

The Internet that we all know and love today looks nothing like the web-landscape of the late 20th Century. So much has changed in the first 20 years of the new millennium in technology and how we use it to interact with your friends and family. For our purposes, we’re going to focus on the issue of mediated friendships in this section. We’ll discuss computer-mediated communication, in general, in Chapter 12.

In the earliest days of online friendships, technology was commonly used to interact with people at larger geographic distances. You met friends in chatrooms or on bulletin boards (precursors to modern social media), and most often, these people were not ones in your town, state, or even country. By 2002, 72% of college students were interacting with their friends online.66 This was the same year Friendster was created, the year before MySpace came into existence, and a solid two years before Facebook was created (February 4, 2004). So, most interaction in 2002 was through email, instant messaging, and chat rooms. Today we talk less about using the Internet and more about what types of applications people are using on their smartphones (the first iPhone came out on June 29, 2007). For example, in 2018, 68% of U.S. adults used Facebook. By comparison, 81% of adults 18 to 29 use Facebook, while only 41% of U.S. adults over the age of 65 are using Facebook.67 What about other common apps? Statistics show that, among US adults, 73% use YouTube, 35% use Instagram, 29% use Pinterest, 27% use Snapchat, 25% use LinkedIn, 24% use Twitter, and 22% use WhatsApp.68

All of these different technologies have enabled us to keep in touch with each other in ways that didn’t exist at the beginning of the 21st Century. As such, the nature of the terms “friend” and “friendship” have changed. For example, how does one differentiate between a friend someone has primarily online and a friend someone sees face-to-face daily? Does the type of technology we use help us explain the nature of our friendships? Let’s explore both of these questions.

What’s a Friend?

As mentioned at the very beginning of this chapter, one of the biggest changes to the story of friendships has been the dilution of the term “friendship.” In some ways, this dilution is a result of social networking sites like Friendster, Facebook, Snapchat, Instagram, etc. Today, we friend people on Facebook that we wouldn’t have had any contact with 20 years ago. We have expanded the term “friend” to include everything from casual acquaintances to best friends. When we compare William Rawlins’ six stages of friendships to how we use the term “friend” in the mediated context, we see that everything from friendly relations to stabilized friendships gets the same generic term, “friend.”69

One Australian writer, Mobinah Ahmad realized that the term “friend” was being widely used and often didn’t fit the exact nature of the relationships she experienced. She created a six stage theory (see sidebar) to express how she views the nature of friendships in the time of Facebook. She started by analyzing her 538 “friends” on Facebook. The overwhelming majority of these friends really were acquaintances. In fact, of the 538 friends Ahmad had, she claimed that only one of them was a “true friend.”70

Friendship Acquaintance Six Stage Theory

Dear person reading this,

Find out where you fit in and the next time I tell you we aren’t friends don’t get offended. Now you’ll know why. Love, Moby. P.S. This is not some exclusive thing, where I’m telling people they’re unworthy. It’s telling it like it is.

PreAcquaintance (10% of people I know)

- We don’t know each other.

- We know each other’s name only.

Acquaintance Level 1: To know of someone 20% of people I know

- We know of each other through mutual friends/acquaintances.

- We met briefly at a party/social event/university.

- You’re a work colleague or business client (who I haven’t spent much time with).

- We run into each other now and then by coincidence.

- Convenient Interactions Meeting up is not planned, and only because it is convenient and easy.

- Details about each other are superficial.

Acquaintance Level 2: Liking & Preliminary Care 30% of people I know

- We went to school/university together, or have known you for a long period of time.

- We usually meet in groups, rarely one-on-one.

- If you needed my help, I would actively participate in helping them to the best of my ability.

- I can handle a 20-minute smalltalk chat with you, any longer and I will get bored.

Acquaintance Level 3: Significant Connection & Care 25% of people I know

- We have a really good connection.

- We have some very meaningful talks.

- We care a lot about each other.

- We don’t see each other all that much, just now and then when we plan to meet.

PreFriend (AKA Potential Friend) 14% of people I know

- Someone I wish were a friend (as defined below and NOT as society currently defines it)

- I want to spend more time with this person and establish a proper friendship with them.

Friend: Mutual Feelings of Love 1% of people I know

- I care immensely in every domain of their life (academic, physical, mental wellbeing), how their relationships with their loved ones are. I also care about their thoughts, ideas, elations, and fears.

- I can easily give my honest opinion and thoughts.

- This person notices when I am upset through subtle indications.

- I see this person regularly and feel totally comfortable to contact them for a deep and meaningful talk.

- Someone who takes initiative and makes sacrifices to work on this friendship.

- Mutual trust, respect, admiration, forgiveness and unconditional care. Note: If it’s not mutual, then we’re not friends.

Further Notes

- There is no shame in being an acquaintance. I think society has made the word derogatory and that is why it seems offensive. It’s just about being honest.

- Friendship is not that complicated to me (I know, the irony of making up a theory and calling it uncomplicated). There may be a small few that cannot be categorized because there is history and shades of grey but I look at my relationship with most people as being Black or White, categorized, uncomplicated.

- The theory is flexible in the sense that people can go up or down the levels and understands that throughout a dynamic friendship, people become closer or further apart from each other.

- My theory originates from personal experiences. I realize that one of my biggest vulnerabilities is that I’m too sentimental; this theory combats this problem quite efficiently.

- I understand that this theory cannot be applied to everyone, but it significantly helps me.

Reprinted with Permission of the Author, Mobinah Ahmad.

Now that you’ve had a minute to read through Mobinah Ahmad’s six stage theory of friendships and acquaintances, how do you see this playing out in your own life? How many people whom you label as “friends” really are acquaintances?

Technologies and Friendships

Today a lot of our interaction with friends is mediated in some fashion. Whether it’s through phone calls and texts or social media, gaming platforms, Skype, and other interactive technologies, we interact with our friends in new and unique ways. For example, in a study that came out in 2018, found that 60% of today’s teenagers interact with their friends online daily while only 24% see their friends daily.71 Interacting online with people is fulfilling some of the basic functions that used to be filled through traditional face-to-face friendships for today’s modern teenagers. Teens who spend time interacting with others in an online group or forum say that these interactions played a role in exposing them to new people (74%), making them feel more accepted (68%), figuring out important issues (65%), and helping them through tough times in life (55%).

But, are all technologies created equal when it comes to friendships? In a study by Dong Liu and Chia-chen Yang, the researchers set out to determine whether the way we perceive our friendships differs based on the communication technologies we use to interact.72 The researchers examined data gathered from 22 different research samples collected by researchers around the world. Ultimately, they found that there is a difference in how we use technologies to interact with friends. They labeled the two different categories Internet-independent (e.g., calls, texts) and Internet-dependent (e.g., instant messaging, social networking sites, gaming). Of the different technologies examined, “Mobile phone-based channels had stronger associations with friendship closeness, suggesting that phone calls and texting were predominantly used with closest associates.”73 As a side note, the researchers did not find sex differences with regard to communication technologies use and friendship intimacy.

Research Spotlight

In 2018, Bree McEwan, Erin Sumner, Jennifer Eden, and Jennifer Fletcher set out to examine relational maintenance strategies on Facebook among friends. Previous research by McEwan found that there were three different relational maintenance strategies used by members of Facebook:74

- Social Contact – personalizing messages to specific friends via Facebook.

- Relational Assurances – demonstrating one’s commitment to continuing a relationship on Facebook.

- Response Seeking – sending messages to a large number of people via Facebook in the hopes of getting input from an array of people.

In this study, the researchers found that social contact, relational assurances, and response seeking were all positively related to liking, relational closeness, relationship satisfaction, and relationship commitment.

McEwan, B., Sumner, E., Eden, J., & Fletcher, J. (2018). The effects of Facebook relational maintenance on friendship quality: An investigation of the Facebook Relational Maintenance Measure. Communication Research Reports, 35(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824096.2017.1361393

Key Takeaways

- Although there was a historical perception that same-sex friendships were distinctly different, research has shown that there is more overlap between female-female and male-male friendships than there are actual differences.

- J. Donald O’Meara proposed five distinct challenges that opposite-sex relationships have: emotional bond (males and females are raised to see the opposite sex as potential romantic partners and not friends), sexuality (inherent in any opposite-sex friendship between heterosexual couples is sexual attraction), inequality and power (a fact of inequality and power-imbalance, created by our society, will always exist between people in opposite-sex); public relationships (opposite-sex friendships are often misunderstood and devalued in our society in favor of romantic relationships); and opportunity structure (our society often makes it difficult for opposite-sex friendships to develop).

- Cross-group friendships are an important part of our society. The two factors that have been shown to be the most important when developing opposite-sex friendships are time and self-disclosure. First, cross-group friendships take more time to develop as individuals navigate cultural differences in addition to navigating the terms of the friendship itself. Second, effective cross-group friendships are often dependent on the adequacy of self-disclosure. Individuals in cross-group friendships need to discuss not only the surface level issues in our lives, but they need to have deeper, more meaningful disclosures about who they are as individuals.

Exercises

- In your view, what is a postmodern friendship, and why is it an important perspective for communication scholars? Would any of your friendships fall within this framework? Why?

- Think of a time when you’ve had a cross-group friendship. What made it a cross-group friendship? How did this friendship differ from your same-group friendships? How was it similar to your same-group friendships? If you were explaining the importance of cross-group friendships in your life to another, what would you tell them?

- Do you think the word “friend” has been devalued through the use of social media? When you look at Mobinah Ahmad’s six stage theory of friendships, do you agree with her perspective? Why?