8.1: Time Management Strategies

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 24276

Introduction

Do you ever wonder where the hours in the day go? Do some days seem to just fly by—leaving you feeling like there just isn’t enough time to do everything you need to do?

People in modern society often struggle to balance the time-consuming needs of going to school, working, and taking care of families. Even doing the things we love can consume so much time that it becomes stressful or anxiety-producing.

Is there a way to accomplish the things we need to do, along with the things we want to do, each day?

There are many strategies out there for organizing our daily activities. Using skills to arrange our time can help relieve our stress and allow us to take care of a variety of things in our lives. There is nothing quite like sitting down after a long day and feeling like you were productive. Smiling with a sense of satisfaction and accomplishment, you can cross off the items on your to-do list, knowing that you made the most out of the day.

In this lesson, we’ll explore useful ways to organize your days—and even your weeks—to get the most mileage out of your time.

How to Make a Daily To-Do List

We often have many tasks and activities to take care of during the day or throughout the week. When keeping track of responsibilities for work, school, or home, you can make a to-do list to help you stay organized; it can also be an effective way of prioritizing what needs to be done first—or last.

Here are useful ways you can organize the day’s activities:

Step 1: Brainstorm tasks. List all of the tasks you want to get done tomorrow. Each task will become an item on a to-do list. Don’t worry about putting the entries in order or scheduling them yet. List everything you want to accomplish on a sheet of paper or in a notebook. You can also use 3 × 5 cards, writing one task on each card. Cards work well because you can slip them into your pocket or rearrange them, and you never have to copy to-do items from one list to another.

Step 2: Estimate time. For each task you wrote down in Step 1, estimate how long it will take you to complete it. This can be tricky. If you allow too little time, you end up feeling rushed. If you allow too much time, you become less productive. For now, give it your best guess. If you are unsure, overestimate rather than underestimate how long it will take for each task.

Now, pull out your calendar or Time Monitor/Time Plan. A Time Monitor or Time Plan is a structured document where you can plan your day, week, or month—but you can write your activities on your calendar as well. You’ve probably scheduled some hours for events such as classes or work. This leaves the unscheduled hours for tackling your to-do list.

Add up the time needed to complete all of your to-do items. Also add up the number of unscheduled hours in your day. Then compare the two totals. The power of this step is that you can spot time overload in advance. If you have eight hours’ worth of to-do items but only four unscheduled hours, that’s a potential problem. To solve it, proceed to Step 3.

Step 3: Rate each task by priority. To prevent overscheduling, decide which to-do items are the most important, given your available time. One suggestion for making this decision comes from the book How to Get Control of Your Time and Your Life, by Alan Lakein (1973): Simply label each item as A, B, or C.

The A items on your list are tasks that are the most critical. They include assignments that are coming due or jobs that need to be done immediately. Also included are activities that lead directly to your short-term goals.

The B items on your list are important, but less so than the A items. The B items can be postponed, if necessary, for another day.

The C items are often small, easy tasks with no set timeline. They, too, can be postponed.

Once you’ve labeled the items on your to-do list, schedule time for all of the A tasks. The B and C items can be done randomly during the day—when you are in between tasks and are not yet ready to start the next A task. Even if you get only one or two of your A items done, you’ll still be moving toward your goals.

Reference

Lakein, Alan. How to Get Control of Your Time and Your Life. New York: New American Library, 1973.

Make Choices About Focus

When we get busy, we get tempted to do several things at the same time. It seems like such a natural solution: Watch TV and read a textbook. Talk on the phone and outline a paper. Write an e-mail and listen to a lecture. These are examples of multitasking.

There’s a problem with this strategy: Multitasking is much harder than it looks.

Despite the awe-inspiring complexity of the human brain, research reveals that we are basically wired to do one thing at a time (Lien, Ruthruff, and Johnston 2005). One study found that people who interrupted work to check e-mail or surf the Internet took up to 25 minutes to get back to their original task (Thompson 2005). In addition, people who use their cell phones while driving get into more traffic accidents than other drivers do, except for drunk drivers (Medina 2009, 87).

The solution is an old-fashioned one: Whenever possible, take life one task at a time. Develop a key quality of master students—focused attention. Start by reviewing and using the Power Process: Be here now. Then, add the following strategies to your toolbox:

Unplug from technology. To reduce the temptation of multitasking, turn off distracting devices. Shut off your TV, cell phone, computer, and/or tablet. Disconnect from the Internet, unless it’s required for your task. Later, you can take a break to make calls, send texts, check e-mails, or browse the web or social media.

Capture fast-breaking ideas with minimal interruption. Your brain is an expert nagger. After you choose to focus on one task, it might issue urgent reminders about 10 more things you need to do. Keep 3 × 5 cards or paper and a pen handy to write down those reminders. You can take a break later and add them to your to-do list. Your mind can quiet down once it knows that a task has been captured in writing.

Monitor the moment-to-moment shifts in your attention. Whenever you’re studying and notice that you’re distracted by thoughts of doing something else, make a tally mark on a sheet of paper. Simply being aware of your tendency to multitask can help you reclaim your attention.

References

Lien, Mei-Ching, Eric Ruthruff, and James C. Johnston. “Attentional limitations in doing two tasks at once: The search for exceptions.” Current Directions in Psychological Science 15, 2 (2005): 89–93.

Medina, John. Brain Rules: 12 Principles for Surviving and Thriving at Work, Home, and School. Seattle, WA: Pear Press, 2009.

Thompson, Clive. “Meet the lifehackers.” New York Times, October 16, 2005.

Make Choices About Multitasking

Learning how to improve your focus and overall attention can help you be more effective in your academic pursuits. Sometimes, though, we simply may not be able to devote our entire time to the same activity. In that case, it becomes necessary to multitask. Can multitasking be productive or even beneficial? It depends on the situation. Some activities require total focus, while others can be more easily juggled.

Here are some strategies for refining your ability to multitask:

Handle interruptions with care. Some breaking events are so urgent that they call for your immediate attention. When this happens, note what you were doing when you were interrupted. For example, write down the number of the page you were reading or the name of the computer file you were working on. When you return to the task, your notes can help you get up to speed again.

Multitask by conscious choice. If multitasking seems inevitable, then do it with skill. Pair one activity that requires concentration with another activity that you can do almost automatically. For example, studying for your psychology exam while downloading music is a way to reduce the disadvantages of multitasking. Pretending to listen to your children while watching TV is not.

Align your activities with your passions. Our attention naturally wanders when we find a task to be trivial, pointless, or irritating. At those times, switching attention to another activity becomes a way to reduce discomfort.

Handling routine tasks is a necessary part of daily life. But if you find that your attention frequently wanders throughout the day, ask yourself: Am I really doing what I want to do? Do my work and my classes connect to my interests?

If the answer is no, then the path beyond multitasking might call for a change in your academic and career plans. Determine what you want most in life. Then, use the techniques in this lesson to set goals that inspire you. Whenever an activity aligns with your passion, the temptation to multitask loses power.

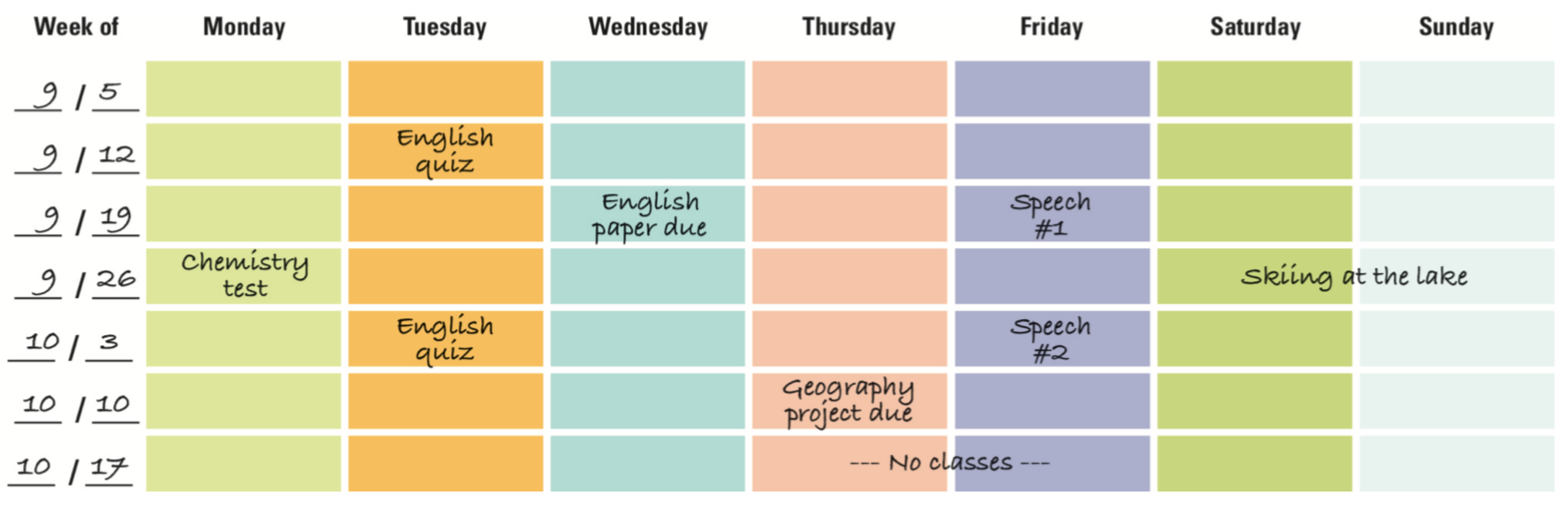

Break It Down, Get It Done: Using a Long-Term Planner

With a long-term planner, you can eliminate a lot of unpleasant surprises. Long-term planning allows you to avoid scheduling conflicts—the kind that obligate you to be in two places at the same time three weeks from now. You can also anticipate busy periods, such as finals week, and start preparing for them now. Goodbye, all-night cram sessions. Hello, serenity.

Find a long-term planner, or make your own. Many office supply stores sell academic planners that cover an entire school year. You can also create your own planner. A big roll of newsprint pinned to a bulletin board or taped to a wall will do nicely. Also search online stores for free or cheap software or smartphone apps designed for long-term planning.

Enter scheduled dates that extend into the future. Use your long-term planner to list commitments that extend beyond the current month. Enter test dates, lab and study sessions, no- classes days or holidays, and planned and other events for the current and next terms.

Create a master assignment list. Find the syllabus for each course you’re currently taking. Then, in your long-term planner, enter the due dates for all of the assignments in all of your courses. This step can be a powerful reality check.

The purpose of using a planner is not to make you feel overwhelmed by all of the things you have to do. Rather, its aim is to help you take a first step toward recognizing the demands on your time. Armed with the truth about how you use your time, you can make more accurate plans.

Include nonacademic events. In addition to tracking academic commitments, you can use your long-term planner to mark significant events in your life outside of school. Include birthdays, doctors’ appointments, concert dates, credit card payment due dates, and car maintenance schedules.

Planning a day, a week, or a month ahead is a powerful practice. Using a long-term planner—one that displays an entire quarter, semester, or year at a glance—can yield even more benefits.

Use your long-term planner to divide and conquer. For some people, academic life is a series of last-minute crises punctuated by periods of exhaustion. You can avoid that fate. The key is to break down big assignments and projects into smaller assignments and subprojects, each with its own due date.

When planning to write a paper, for example, enter the final due date in your long-term planner. Then, set individual deadlines for each milestone in the writing process—creating an outline, completing the research, finishing the first draft, editing the draft, and preparing the final copy. By meeting these interim due dates, you make steady progress toward completing the assignment throughout the term. That sure beats trying to crank out all those pages at the last minute.