1.6: in your context

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 46474

- Susan Carter and Cecily Andersen

- University of Southern Queensland via University of Southern Queensland - Open Access Textbooks

Key Concept

- Ecological and contextual analysis of wellbeing using evidence based and contextual self-assessment.

Guiding question:

- How can wellbeing be enacted and promoted in my context?

Forming connections and fitting in is associated with positive wellbeing. Consider then, how do educational contexts create a sense of connection and belonging.

Introduction

There is increasing understanding that educational contexts have an important role to play in supporting the social and emotional development of children and young people. Interventions undertaken in educational context settings have the potential to influence a range of social, health and mental health outcomes. Evidence suggests that good mental and physical health not only optimises a young person’s academic performance but also enhances the ability to cope with the challenges and stressors of daily life, and thereby to become a productive member of society in the longer term.

We draw your attention to wellbeing considerations for all people but especially challenge you to think about how you meet the needs of people with disabilities, some of whom have a comorbidity of disabilities or special needs, may be profoundly disabled and could also be non-verbal. Consider also the stress factors that may be present in some families who are dealing with very complex and challenging issues. How best can we then understand the complex needs of an individual?

Although wellbeing can be seen principally as relating to the individual, a social conception of wellbeing transfers attention to the interplay of individuals, incorporating the social and cultural dimensions that they arbitrate as contributing to their satisfaction with life. This Chapter explores ecological and contextual analysis of wellbeing using evidence based and contextual self-assessment as a means of understanding the concept of wellbeing from an individual, classroom, educational context, and system perspective, and what is exactly occurring within your own educational community context. In this chapter we also suggest a way of developing a wellbeing framework based upon evidence-based practice and we include numerous practical templates for use or adaption. We acknowledge the limitations of some of the templates when applied in various settings such as early childhood, special education units, and we seek your input to co-create more meaningful resources. Please feel welcome to contact us, our details in the Foreword section of this book.

Activity

Before undertaking an ecological and contextual analysis of wellbeing within your own context, consider what both terms might mean for you, and how they might apply to your context.

Let’s now examine how literature defines contextual and ecological analysis. Spencer (2007) defines ecological analysis as an investigation of the relationship between individuals and each other, and their relationship to their physical surroundings. Wu and David (2002) expanded this a little further by proposing that individuals’ perceptions about settings and their experiences within an environment matter, and that ecological analysis is a process of understanding how individuals’ experiences contribute to ‘making sense’ of situations and experiences negotiated progressively over time and place. Thus, an ecological analysis of wellbeing provides an opportunity to investigate the wide variety of bidirectional, and individual-context interactions that in turn, contribute to the construct that is well being. George et al., (2015) define context as the circumstances that impact on a setting or event, and contextual analysis as the process of understanding the broader range of relationships that influence the outcome of a subject being investigated within that setting or event. Thus, according to Smith, Montagno, and Kuzmenko (2004), a contextual analysis is an analysis of a context within both its historical and cultural setting, the qualities that characterize it, and the characteristics of the ecology/environment that influence these.

An ecological and contextual analysis of wellbeing within a specific context /worksite offers an opportunity to investigate information about whether or not an approach / strategy / intervention ‘fits’ within the context in which it has been implemented, and provides a ‘snapshot’ of measurable community characteristics and evidence as to whether a wellbeing strategy has been implemented effectively, has been useful, and/ or has been accepted by a particular community.

Factors influencing wellbeing

The World Health Organization {WHO} (2013) identifies supporting environments for well-being to be a key responsibility of educational contexts. WHO (2013) points to a range of research which has found that educational context connectedness, or the feeling of closeness to context staff and the context’s environment decreases the likelihood of health risk behaviours during adolescence. Educational contexts with a climate of confidence and respect among principals,staff,pupils and parents reflect the lowest rates of general anxiety,school anxiety and emotional and psychosomatic balance among children and young people.

“A positive educational experience and a good level of academic achievement can contribute significantly to enhancing self-esteem and confidence, better employment, life opportunities and social support” (Department of Education and Skills Health Service Executive and Department of Health {DESHSEDH}, 2013, p.8). Life skills education, strongly supported by Weare and Nind (2011) and the WHO (2013), are viewed as a preventive measures for a range of health and social problems, and include the development of skills such as: decision making/ problem solving; creative thinking/ critical thinking; communication/ interpersonal skills; self-awareness/ empathy; coping with emotions/ coping with stress. In contrast, poor engagement and achievement in an educational context setting is a risk factor for a range of social, health and mental health problems such as substance misuse, unwanted teenage pregnancy, crime and conduct problems.

A study by Kidger, Gunnell, Biddle, Campbell, and Donovan (2010) identified that teachers also were a key factor influencing the emotional health and well being of students. However, Kidger et al. (2010) also noted that in instances where teachers’ own emotional health needs were neglected, this left them with little ability, and in some cases an unwillingness, to cater for the wellbeing of students. The findings from the study conclusively endorsed whole-school approaches to wellbeing which also focused on teachers’ training and support needs. This study highlights the importance of wellbeing programs that focus on the whole educational community context, fore fronting the health and wellbeing of all staff and all students.

Broadly speaking then, factors that have an influence on wellbeing across all populations can be grouped into three key areas: individual, community and structural.

Key Questions

Consider your own context for a moment.

- What factors influence wellbeing within your own context? What factors can your school influence?

- What supports are currently in place within your context that support the positive development of wellbeing?

Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory

Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) Ecological Systems Theory summarised decades of theory and research about the fundamental progressions that guide life-span development, and stressed the importance of studying an individual within the context of the multiple environments in which they are positioned (Darling, 2007). Bronfenbrenner defined this as an ecological system which contributed to understanding of how a person grows and develops, which in turn develops a deeper understanding of individuals, their needs and their wellbeing. Ecological Systems Theory then has potential to be a useful framework for understanding how inherent qualities of an individual’s environment interacts to influence how they develop and grow.

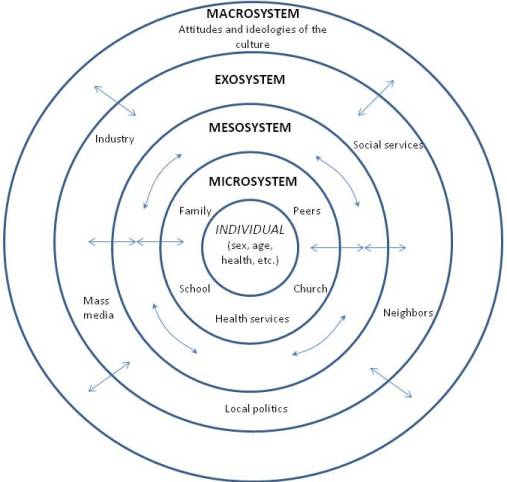

Within this theory, Bronfenbrenner (1979) devised classifications for various levels and degrees of intervening influence on a person’s development, with these systems referred to as a “system of layers, with each layer located inside the other, similar to that of Russian nesting dolls” (Bronfenbrenner, 1979, p. 22). Bronfenbrenner’s perspective reinforced the critical and pervasive role that the Microsystem {the immediate environment of the individual including everyone that they interact with on a regular basis.}; the Mesosystem {the interaction between members/components of the microsystem}; the Exosystem {the broader environment that directly affects the immediate environment of the individual}; the Macrosystem{the overarching system that consists of culture, laws, economy, politics, etc}; and the Chronosystem {how certain variable affect the individual over time, including life events and changes in socioeconomic status} had on influencing an individual’s behaviour, as shown in Figure 6.2.

Since Bronfenbrenner’s initial Ecological Systems Theory theory was proposed, Bowes and Hayes (1999) have added several other components to Bronfenbrenner’s model. Firstly, individual characteristics were introduced, such as temperament and gender, followed by the addition of historical factors impacting on current behaviours attitudes and practices, with the acknowledgment that these vary over time.

Within this extended Ecological Systems Theory model:

- The microsystem is the smallest and most immediate and most intimate of environments {e.g., daily home}, and includes those interactions which occur closest to the individual.

- The mesosystem includes the interaction of the different microsystems such as, linkages between home and school, between peer group and family.

- The exosystem pertains to the linkages that may exist between two or more settings, one of which may not contain the child or young person but affects the child or young person indirectly. This could be other people and places which the child or young person may not directly interact with but may still have an effect on the child or young person {e.g., care giver’/ parents’ workplaces}.

- The macrosystem, understood to be more distant from the child or young person, includes influences such as cultural beliefs, values and practices from the wider community. Bronfenbrenner (1995) claimed that we experience “progressively more complex reciprocal interaction between an active evolved bio-psychological human organism and the persons, objects, and symbols in its immediate environment… this interaction must occur on a fairly regular basis…. Such enduring forms of interaction in the immediate environment are referred to as proximal processes” (Bronfenbrenner, 1995, p.621).

- The chronosystem contributes the useful dimension of time, which demonstrates the influence of both change and constancy in the child’s / young person’s environment. The chronosystem may therefore include a change in family structure, residence, parental employment status, and social and political changes such as housing market crashes. Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory is useful beyond the developing child / young person but has application to any individual’s development.

Activity

Consider Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model and reflect on how this model may be useful in helping teachers to better understand and support their students.

Other researchers have applied and adapted Bronfenbrenner’s model to understandings about particular disabilities. A biomedical model has powerfully shaped and historically been a key way of understanding and supporting mental health in children and young people (Deanon, 2013). More recently, the emergence of a body of early childhood and health literature has recognised the influence which biological, psychological and social factors can have on children’s / young people’s health, learning and development. (Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing {ADHA}, 2014)

However, while the Ecological Systems Theory Model offers a potential framework for use in an ecological and contextual analysis of wellbeing within a educational context and community, Armitage, Béné, Charles, Johnson, and Allison (2012) argue that caution needs to be exercised in using only one framework or approach in the analysis of wellbeing. Instead Armitage et al., (2012) propose “the development of hybrid approaches and innovative combinations of social and ecological theory in order to provide signposts and analytical tools to understand complexity and change” (p.12) with an educational context.

Activity

Consider your own context for a moment and the supports that you believe are in place for the positive development of wellbeing.

- Construct an ecological model for yourself and your own wellbeing in your work context.

- Construct an ecological model for someone whose wellbeing you are concerned about in your work context.

Developing an educational context framework

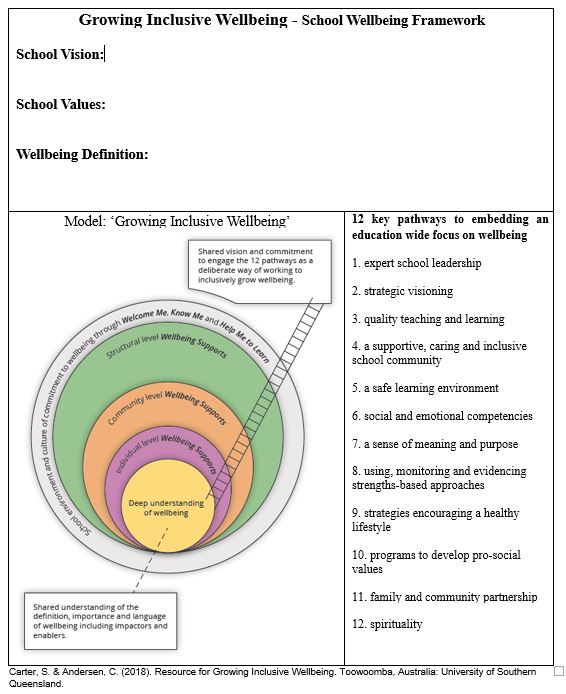

It is suggested that educational contexts develop a framework to ensure that wellbeing is an explicit focus within the educational community. The question then becomes, what goes into the framework. Reviewing the information shared in Chapter 3, Garrison (2011) defined a framework as a set of beliefs, rules or thinking that outline what actions can be undertaken. White (2010) suggested that a wellbeing framework is “a social process with material, relational, and subjective dimensions” (p.158). We suggest that a wellbeing framework should align with the beliefs and values espoused by the educational community context; clearly outline the shared definition underpinned by a deep knowledge of the possible impactors and enablers to wellbeing; include pathways for enactment; and ways it be evaluated at individual, community and structural levels where educational context community input is sought with open communication and relationships as central components. We suggest that your framework begins with your educational context vision and beliefs. In the following section we suggest that you use a model, guiding questions and a checklist and surveys to evaluate your progress.

How is wellbeing evidenced

At the start of the chapter we posed a guiding question for you to consider. The guiding question was how is wellbeing enhanced? How do you know what you know about wellbeing? What are you using to evidence your judgements? What follows are photographic examples, and resources for use in educational contexts that have been developed to assist you in investigating wellbeing within your own educational communities. The resources have been provided as a guide, a way of working to inform your wellbeing journey, and as a means of ensuring that your judgements are evidenced based. The examples may be adapted to suit different models and educational communities. We suggest that you use a variety of artefacts to evidence practice. This gathering of evidence could be done at a classroom level by individual teachers; a year levels/ teaching teams; and a whole of educational context level.

School examples of practice

Creating a sense of belonging where people are connected to the educational context , feel safe and also know that they have realistic learning opportunities, helps to nurture wellbeing. We have taken a variety of photographs to help model how elements of wellbeing promotion can be evidenced. There are many ways to see wellbeing within an educational context, and the following (Figures 6.3, 6.4, 6.5 and 6.6) illustrate a small snapshot of possible ideas.

Values are clearly displayed in multiple places throughout the school contributing to a culture of care and respect for other (see Figure 6.3). These same values are on display in all classrooms beside the positive behaviour expectations, in every play space, in the office, the staffroom and the meeting rooms, are linked to verbally in every parade, and associated with positive reinforcement through STAR awards.

Educational contexts should be committed to providing safe, inviting and welcoming learning spaces so that students experience a feeling of belonging. These spaces should also be places of quality learning and teaching where the learning needs of each individual are acknowledged and catered for so that success as determined differently by each individual, can be experienced and celebrated (as shown in Figure 6.4).

Pictured below in Figure 6.5 is the intensive learning classroom which is rich in visual scaffolding helping to support the delivery of explicit instruction.

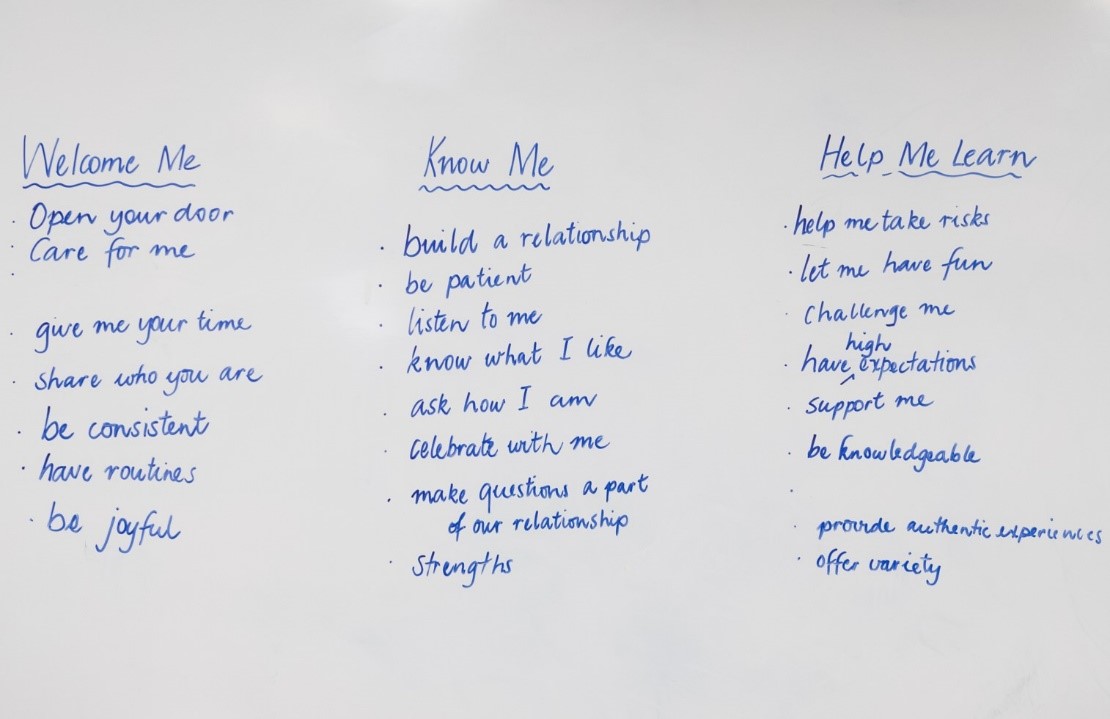

Below in Figure 6.6, a shared language is evidence around the establishment of a shared professional dialogue and way of working where all students are welcome, teachers are challenged to create a sense of belonging for every student and the needs of individual students are a key focus through ‘Welcome Me, Know Me, and Help Me to Learn’.

This photograph captures a way of working where the needs of the child are fore fronted and the focus is on student engagement in learning. The photograph was taken in the meeting room and ‘Welcome Me’, ‘Know Me’, and ‘Help Me Learn’ regularly featured in pedagogical discussion, year levels meetings and staff meetings. Teachers and teacher aides are also engaged in professional development opportunities to further enhance their understanding was to be enacted.

Resources for use in schools to formulate a wellbeing framework

We suggest that your framework begins with your educational context vision and beliefs. We assume that this has already been developed and regularly reviewed with your context’s annual plan. By linking it specifically to the wellbeing framework alignment can be scaffolded.

- In the following section we suggest that you use a model and we have provided a template:

- Table 6.1 Growing Inclusive Wellbeing, in a word format (also shown as Figure 6.7)

- We have then provided a list of guiding questions:

- Table 6.2 Guiding Questions

- There is also a possible checklist/ brainstorm sheet for data gathering of possible impactors and enablers and potential school response actions.

- Table 6.3 Checklist for enablers and impactors.

- We have provided a checklist for data gathering information about whole school wellbeing.

- Table 6.4 Whole educational community growing inclusive wellbeing checklist

- We have linked a variety of surveys to inform your thinking and these surveys are targeted at different groups.

- Table 6.5 Survey on wellbeing;

- Table 6.6 Individual level growing inclusive wellbeing checklist for the Principal and school staff;

- Table 6.7 Individual wellbeing level growing inclusive wellbeing checklist for students

While we have provided the surveys in a template form there is no reason that these surveys could to be redeveloped and used in a multi-modal format (e.g., Survey Monkey) and made to suit your specific context. In providing a range of surveys it is hoped that you can select what best suits your context and /or to use different surveys at differing times of the year and cross validate the data findings {e.g., beginning or end of the year}.

Start with the vision, values and a model

The text in the following section has the various resources, labelled as Tables, hyperlinked as word documents so that you can use the resources and personalise them for your context. We suggest you start with a model (word form hyperlinked here (Table 6.1 Growing Inclusive Wellbeing), also shown below as a snapshot of the template (Figure 6.7: ‘Growing Inclusive Wellbeing’).

Guiding questions for schools

We recognise that educational contexts are unique contexts full of creative people and we expect that each educational context will generate other questions to guide their designing, enacting and reflecting upon wellbeing. We know that educational contexts are also busy places and that judgments are made that are not always evidenced based and these judgments are not always correct. We encourage critical reflection and challenge you to try to uncover assumptions and practices that may or may not promote wellbeing. Further to this we hope that every educational contexts endeavours to engage all members in growing inclusive wellbeing. In the Hyperlinked activity below, we provide some guiding questions to help school communities on their journey with wellbeing. We also provide some challenge questions around a simple thinking frame of ‘Welcome Me’, ‘Know Me’, and ‘Help Me Learn’.

This way of thinking – ‘Welcome Me’, ‘Know Me’, and ‘Help Me Learn’, when enacted can become part of an embedded inclusive culture that enables wellbeing for everyone. People can use this to support the special needs of each individual whether they are a student, a parent, a teacher or another staff member.

Scenario

Angela, a new single mother arrives at the school and enrolls her year 6 child Jo. Upon enrollment Angela is introduced to the school community liaison officer who takes the time to try and get to know Angela and establish the beginnings of a positive relationship with Angela. This is the ‘welcome me’ in action.

Jo, the year 6 student is away from school for several days.

Activity

- What assumption does the class teacher make? What action needs to occur?

As part of the ‘Welcome Me’ a possible way of working that may help to establish educational context belonging is for the educational context community liaison officer, as part of their regular routine work, to call the family on day three at the school, at the end of week 2 and then at the end of term. Imagine if the parent liaison officer telephones the mother and it is revealed that the mother’s car has broken down and she cannot afford to fix it and so has no way of getting Jo to school. This is the ‘Know Me’ in action. With this information the parent liaison officer can then utilise networks and contextual understandings and linkage with others to ensure that Jo is transported to and from school. Consider how this may benefit Jo in terms of learning, engage, school connectedness and wellbeing. If the community liaison officer makes Angela and Jo aware of the local bus and church community groups that can help ensure transport to and from shops and possible medical appointments while Angela is saving money to fix the car, this then becomes the ‘Help Me Learn’. Angela and Jo can then learn about how to link into community networks to ensure their needs are meet. The expectation is then not one of learned helplessness but one of learning how to engage with school community networks. Consider also if Angela had English as a second language and was a refugee. Consider how hard would it be for Jo to engage in quality teaching and learning and have positive wellbeing. ‘Welcome Me, Know Me and Help Me to Learn’ can be enacted for anyone through whole school community commitment and a shared knowledge language and way of working. In Table 6.2 Guiding Questions, we model a way of questioning that links to ‘Welcome Me, Know Me and Help Me to Learn’.

Hyperlinked here is a word document which may be of use, Table 6.3 Checklist for Enablers and Impactors which outlines a possible brainstorm list that schools can use to consider impactors and enablers. This checklist is useful to explore:

- Can impactors be mitigated? If so how?

- Can enablers be further developed? If so How?

We have not listed all of the impactors and enablers, rather we have brainstormed a base list that school communities can add to and contextualise. We suggest using this checklist firstly from the perspective of the individual child, or individual teacher, individual principal or other staff member. This could be completed by the individual themselves and then the how do you know conversation could involve a buddy, mentor, or trusted other person. We then suggest that this same sheet could be of use when you look from the educational context‘s community perspective (e.g. what supports are evident from the context’s community for an individual with their academic performance; with their homework etc) and this should be done with input from all stakeholder groups, staff, students and parents/caregivers.

Growing Inclusive Wellbeing Checklist

The following evidence-based practice checklist utilises the 12 pathways to wellbeing (outlined in chapter 5). In this checklist evidence refers to information, processes, strategies, ways of working and data that are implemented or happening in the context. Evidence provides information in relation to whether a process, strategy or way of working, is feasible to implement; useful; likely to be accepted by a school community; and whether it is a potential vehicle for change. The term artefact refers to those items, things, policies and awards, that are captured in moment {e.g., a photograph} and these are physical forms of evidence. Evidence such as artefacts offer a ‘snapshot’ of wellbeing within an educational community context. Please use Table 6.4 Whole Educational Community Growing Inclusive Wellbeing Checklist.

Survey on wellbeing

We suggest that you work with all stakeholder groups and alter the wording on the survey captured here in Table 6.5 Survey on wellbeing . We have also included here an individual survey for the educational leader / principal/ school staff which can be modified to best suit your context, captured here in Table 6.6 Individual level growing inclusive wellbeing checklist for the Principal and School Staff . We have also included an individual survey captured her in Table 6.7 Individual wellbeing level- growing inclusive wellbeing checklist for students that specifically targets students and we encourage you to modify it so it is age appropriate and context specific . The surveys are designed to find out what works and what isn’t working and ways for improvement. We strongly encourage educational contexts to build upon their strengths. The surveys can be used in conjunction with normal data gathering cycles and may be useful in informing evidenced-based student and staff engagement discussions. The educational community can then consider how to collate, share, analyse and respond to the data and we suggest that existing committee structures could be used so a focus on wellbeing becomes an embedded way of working.

Summary

This chapter explored the ecological and contextual analysis of wellbeing using evidence based and contextual self-assessment as a means of understanding the concept of wellbeing from an individual, educational context, and system level, and challenges educational communities to review what is occurring within their context. Research clearly highlights the importance of a whole of context approach on wellbeing. As authors and educators, we hope that the material shared within this text has been useful in furthering your understanding of wellbeing and in offering suggestions for the development and implementation of a whole education context wellbeing program and focus.

References

Armitage, D., Béné, C., Charles, A., Johnson, D., & Allison, E. (2012). The interplay of well-being and resilience in applying a social-ecological perspective. Ecology and Society, 17 (4). doi:10.5751/ES-04940-170415

Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing {DHA}. (2014). Understanding mental health in early childhood. Retrived from http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/DoHA-MedicareMOU

Bowes, J.M. & Hayes, A. (1999). Children, families and communities: Contexts and consensus. South Melbourne, VIC: Oxford University Press. Retrieved from https://aifs.gov.au/publications/parenting-australian-families/2-parenting-and-socio-cultural-context

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1995). Developmental psychology through space and time. In P. Moen, G. Elder Jr & K. Luscher (Eds.), Examining lives in context, (pp. 619-647). Washington DC: American Psychological Association Press.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (2004). Making human beings human: Bioecological perspectives on human development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (2005). Ecological systems theory. In U. Bronfenbrenner (Ed.), Making human beings human: Bioecological perspectives on human development, (pp. 106-173). Thousand Oaks, CA.: Sage Publications.

Darling, N. (2007). Ecological systems theory: The person in the center of the circles. Research in Human Development, 4 (3-4), 203-217. doi: 10.1080/15427600701663023

Deanon, B. (2013). The biomedical model of mental disorder: A critical analysis of its validity, utility, and effects on psychotherapy research. Clinical Psychology Review, 33 (7), 846-861. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.09.007

Department of Education and Skills Health Service Executive and Department of Health {DESHSEDH}. (2013). Well-Being in post-primary schools: Guidelines for mental health promotion and suicide prevention. Dublin, Ireland: Department of Education and Skills, Health Service Executive, and Department of Health.

Garrison, R. (2011). E-learning in the 21st century: A framework for research and practice (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

George, A., Scott, K., Surekha, G., Shinjini, M., Rajani, V. & Kabir, S. (2015). Anchoring contextual analysis in health policy and systems research: A narrative review of contextual factors influencing health committees in low- and middle-income countries. Social Science & Medicine, 133, 159-167.

Kidger, J., Gunnell, D., Biddle, L., Campbell, R., & Donovan, J. (2010). Part and parcel of teaching? Secondary school staff’s views on supporting student emotional health and well‐being. British Educational Research Journal, 36 (6), 919-935.

Layton, N. A., & Steel, E. J. (2015). An environment built to include rather than exclude me: Creating inclusive environments for human well-being. International journal of environmental research and public health, 12(9), 11146-11162.

Smith, B. N., Montagno, R. V., & Kuzmenko, T. N. (2004). Transformational and servant leadership: Content and contextual comparisons. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 10 (4), 80-91. doi:10.1177/107179190401000406

Spencer, M.B. (2007). Phenomenology and ecological systems theory: Development of diverse groups. In W. Damon and R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of Child Psychology, (pp.696- 740). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. doi: 10.1002/9780470147658.

Weare, K. & Nind, M. (2011). Mental health promotion and problem prevention in schools: what does the evidence say? Health Promotion International, 26 (1), 29-69. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dar075

White, S.C. (2010). Analysing wellbeing: a framework for development practice. Development in Practice, 20 (2), 158-172. doi: 10.1080/09614520903564199

World Health Organisation {WHO}. (2013). Mental health action plan for 2013-2020. Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/89966/1/9789241506021_eng.pdf?ua=1

Wu, J. & David, J. L. (2002). A spatially explicit hierarchical approach to modelling complex ecological systems: theory and applications. Ecological Modelling, 153 (1-2), 7-26. doi:10.1016/S0304-3800(01)00499-9