4.3: Types of Assignments

- Page ID

- 133160

Introduction

As discussed in the previous chapter, assignments are a common method of assessment at university. You may encounter many assignments over your years of study, yet some will look quite different from others. By recognising different types of assignments and understanding the purpose of the task, you can direct your writing skills effectively to meet task requirements. This chapter draws on the skills from the previous chapter, and extends the discussion, showing you where to aim with different types of assignments.

The chapter begins by exploring the popular essay assignment, with its two common categories, analytical and argumentative essays. It then examines assignments requiring case study responses, as often encountered in fields such as health or business. This is followed by a discussion of assignments seeking a report (such as a scientific report) and reflective writing assignments, which are common in nursing, education, and human services. The chapter concludes with an examination of annotated bibliographies and literature reviews. The chapter also has a selection of templates and examples throughout to enhance your understanding and improve the efficacy of your assignment writing skills.

Different Types of Written Assignments

Essay

At university, an essay is a common form of assessment. In the previous chapter Writing Assignments, we discussed what was meant by showing academic writing in your assignments. It is important that you consider these aspects of structure, tone, and language when writing an essay.

Components of an essay

Essays should use formal but reader-friendly language and have a clear and logical structure. They must include research from credible academic sources such as peer reviewed journal articles and textbooks. This research should be referenced throughout your essay to support your ideas (see the chapter Working with Information).

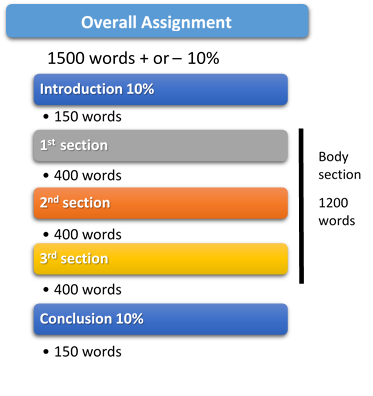

If you have never written an essay before, you may feel unsure about how to start. Breaking your essay into sections and allocating words accordingly will make this process more manageable and will make planning the overall essay structure much easier.

- An essay requires an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion.

- Generally, an introduction and conclusion are each approximately 10% of the total word count.

- The remaining words can then be divided into sections and a paragraph allowed for each area of content you need to cover.

- Use your task and criteria sheet to decide what content needs to be in your plan

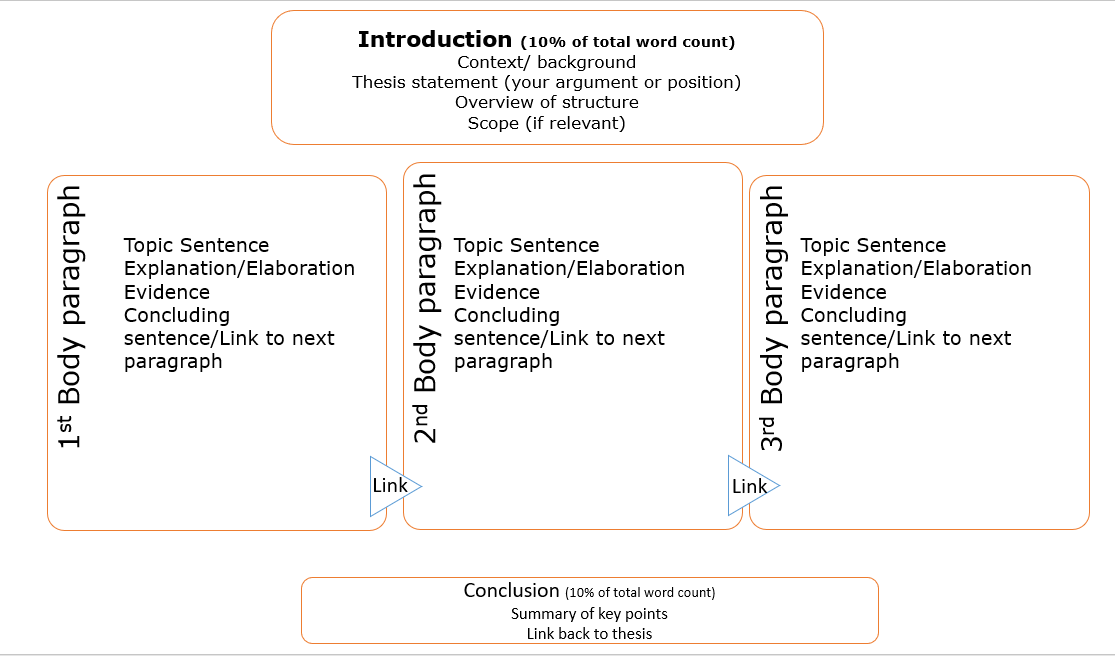

An effective essay introduction needs to inform your reader by doing four basic things:

| 1 | Engage the reader’s interest and provide a brief background of the topic. |

| 2 | Provide a thesis statement. This is the position or argument you will adopt. (Note that a thesis statement is not always required. Check with your tutor). |

| 3 | Outline the structure of the essay. |

| 4 | Indicate any parameters or scope that will/will not be covered. |

An effective essay body paragraph needs to:

| 1 | State the topic sentence or main point of the paragraph. If you have a thesis statement, the topic sentence should relate to this. |

| 2 | Expand this main idea, define any terminology, and explain concepts in more depth. |

| 3 | This information should be paraphrased and referenced from credible sources according to the appropriate referencing style of your course. |

| 4 | Demonstrate critical thinking by showing the relationship of the point you are making and the evidence you have included. This is where you introduce your “student voice”. Ask yourself the “So what?” question (as outlined in the critical thinking section) to add a discussion or interpretation of how the evidence you have included in your paragraph is relevant to your topic. |

| 5 | Conclude your idea and link to your next point. |

An effective essay conclusion needs to:

| 1 | Summarise or state the main points covered, using past tense. |

| 2 | Provide an overall conclusion that relates to the thesis statement or position you raised in your introduction. |

| 3 | Not add any new information. |

Common types of essays

You may be required to write different types of essays, depending on your study area and topic. Two of the most commonly used essays are analytical and argumentative. The task analysis process discussed in the previous chapter Writing Assignments will help you determine the type of essay required. For example, if your assignment question uses task words such as analyse, examine, discuss, determine, or explore, then you would be writing an analytical essay. If your assignment question has task words such as argue, evaluate, justify, or assess, then you would be writing an argumentative essay. Regardless of the type of essay, your ability to analyse and think critically is important and common across genres.

Analytical essays

These essays usually provide some background description of the relevant theory, situation, problem, case, image, etcetera that is your topic. Being analytical requires you to look carefully at various components or sections of your topic in a methodical and logical way to create understanding.

The purpose of the analytical essay is to demonstrate your ability to examine the topic thoroughly. This requires you to go deeper than description by considering different sides of the situation, comparing and contrasting a variety of theories and the positives and negatives of the topic. Although your position on the topic may be clear in an analytical essay, it is not necessarily a requirement that you explicitly identify this with a thesis statement. In an argumentative essay, however, it is necessary that you explicitly identify your position on the topic with a thesis statement. If you are unsure whether you are required to take a position, and provide a thesis statement, it is best to check with your tutor.

Argumentative essays

These essays require you to take a position on the assignment topic. This is expressed through your thesis statement in your introduction. You must then present and develop your arguments throughout the body of your assignment using logically structured paragraphs. Each of these paragraphs needs a topic sentence that relates to the thesis statement. In an argumentative essay, you must reach a conclusion based on the evidence you have presented.

Case study responses

Case studies are a common form of assignment in many study areas and students can underperform in this genre for a number of key reasons.

Students typically lose marks for not:

- Relating their answer sufficiently to the case details.

- Applying critical thinking.

- Writing with clear structure.

- Using appropriate or sufficient sources.

- Using accurate referencing.

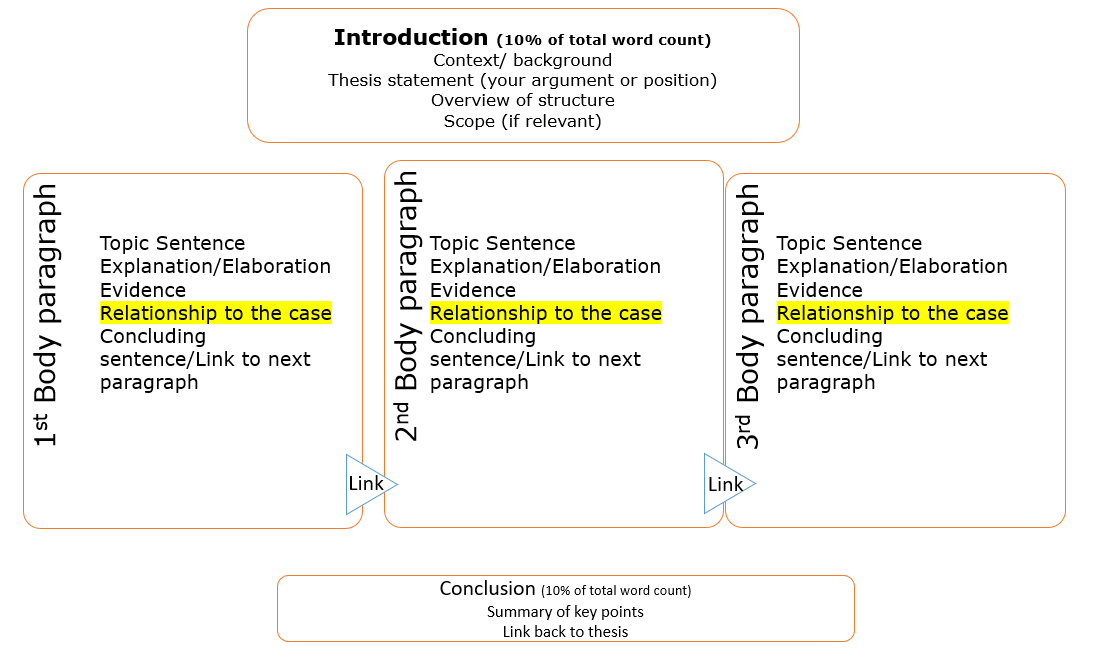

When structuring your response to a case study, remember to refer to the case. Structure your paragraphs similarly to an essay paragraph structure, but include examples and data from the case as additional evidence to support your points (see Figure 68). The colours in the sample paragraph below show the function of each component.

The Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia (NMBA) Code of Conduct and Nursing Standards (2018) play a crucial role in determining the scope of practice for nurses and midwives. A key component discussed in the code is the provision of person-centred care and the formation of therapeutic relationships between nurses and patients (NMBA, 2018). This ensures patient safety and promotes health and wellbeing (NMBA, 2018). The standards also discuss the importance of partnership and shared decision-making in the delivery of care (NMBA, 2018, 4). Boyd and Dare (2014) argue that good communication skills are vital for building therapeutic relationships and trust between patients and care givers. This will help ensure the patient is treated with dignity and respect and improve their overall hospital experience. In the case, the therapeutic relationship with the client has been compromised in several ways. Firstly, the nurse did not conform adequately to the guidelines for seeking informed consent before performing the examination as outlined in principle 2.3 (NMBA, 2018). Although she explained the procedure, she failed to give the patient appropriate choices regarding her health care.

Topic sentence | Explanations using paraphrased evidence including in-text references | Critical thinking (asks the so what? question to demonstrate your student voice). | Relating the theory back to the specifics of the case. The case becomes a source of examples as extra evidence to support the points you are making.

Report

Reports are a common form of assessment at university and are also used widely in many professions. It is a common form of writing in business, government, scientific, and technical occupations.

Reports can take many different structures. A report is normally written to present information in a structured manner, which may include explaining laboratory experiments, technical information, or a business case. Reports may be written for different audiences, including clients, your manager, technical staff, or senior leadership within an organisation. The structure of reports can vary, and it is important to consider what format is required. The choice of structure will depend upon professional requirements and the ultimate aims of the report. Consider some of the options in the table below (see Table 18.2).

| Executive or Business Reports | Overall purpose is to convey structured information for business decision making. |

| Short form or Summary Reports | Are abbreviated report structures designed to convey information in a focused short form manner. |

| Scientific Reports | Are used for scientific documentation purposes and may detail the results of research or describe an experiment or a research problem. |

| Technical Reports | Are used to communicate technical information for decision making, this may include discussing technical problems and solutions. |

| Evaluation Reports | Present the results of or a proposal for an evaluation or assessment of a policy, program, process or service. |

Reflective writing

Reflective writing is a popular method of assessment at university. It is used to help you explore feelings, experiences, opinions, events, or new information to gain a clearer and deeper understanding of your learning.

A reflective writing task requires more than a description or summary. It requires you to analyse a situation, problem or experience, consider what you may have learnt, and evaluate how this may impact your thinking and actions in the future. This requires critical thinking, analysis, and usually the application of good quality research, to demonstrate your understanding or learning from a situation.

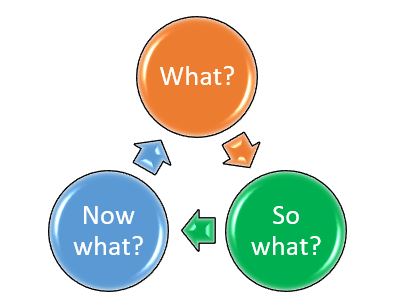

Essentially, reflective practice is the process of looking back on past experiences and engaging with them in a thoughtful way and drawing conclusions to inform future experiences. The reflection skills you develop at university will be vital in the workplace to assist you to use feedback for growth and continuous improvement. There are numerous models of reflective writing and you should refer to your subject guidelines for your expected format. If there is no specific framework, a simple model to help frame your thinking is What? So what? Now what? (Rolfe et al., 2001).

| What? | Describe the experience – who, what, why, when, where? |

| So what? | What have you learnt from this? Why does it matter? What has been the impact on you? In what way? Why? You can include connections to coursework, current events, past experiences. |

| Now what? | What are you going to do as a result of your experience? How will you apply what you have learnt in the future? Are there critical questions to further pursue? Make an action plan of what you will do next. |

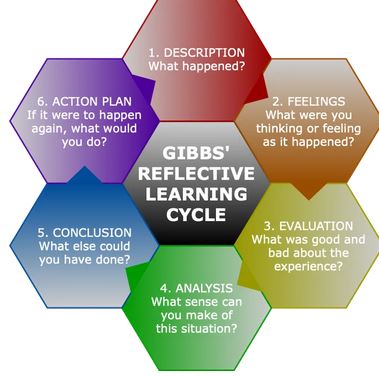

The Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle

The Gibbs’ Cycle of reflection encourages you to consider your feelings as part of the reflective process. There are six specific steps to work through. Following this model carefully and being clear of the requirements of each stage, will help you focus your thinking and reflect more deeply. This model is popular in Health.

The 4 R’s of reflective thinking

This model (Ryan and Ryan, 2013) was designed specifically for university students engaged in experiential learning. Experiential learning includes any ‘real-world’ activities, including practice led activities, placements, and internships. Experiential learning, and the use of reflective practice to heighten this learning, is common in Creative Arts, Health, and Education.

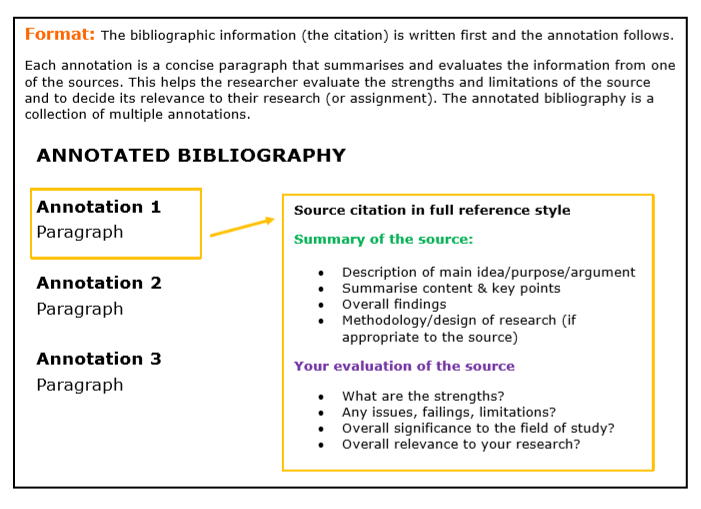

Annotated bibliography

What is it?

An annotated bibliography is an alphabetical list of appropriate sources (e.g. books, journal articles, or websites) on a topic, accompanied by a brief summary, evaluation, and sometimes an explanation or reflection on their usefulness or relevance to your topic. Its purpose is to teach you to research carefully, evaluate sources and systematically organise your notes. An annotated bibliography may be one part of a larger assessment item or a stand-alone assessment item. Check your task guidelines for the number of sources you are required to annotate and the word limit for each entry.

How do I know what to include?

When choosing sources for your annotated bibliography, it is important to determine:

- The topic you are investigating and if there is a specific question to answer.

- The type of sources on which you need to focus.

- Whether these sources are reputable and of high quality.

What do I say?

Important considerations include:

- Is the work current?

- Is the work relevant to your topic?

- Is the author credible/reliable?

- Is there any author bias?

- The strength and limitations (this may include an evaluation of research methodology).

Literature reviews

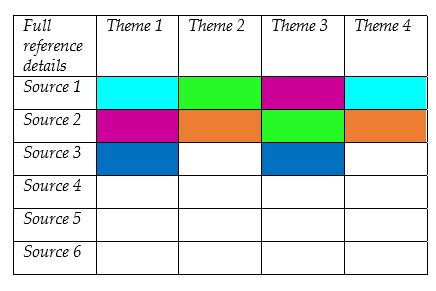

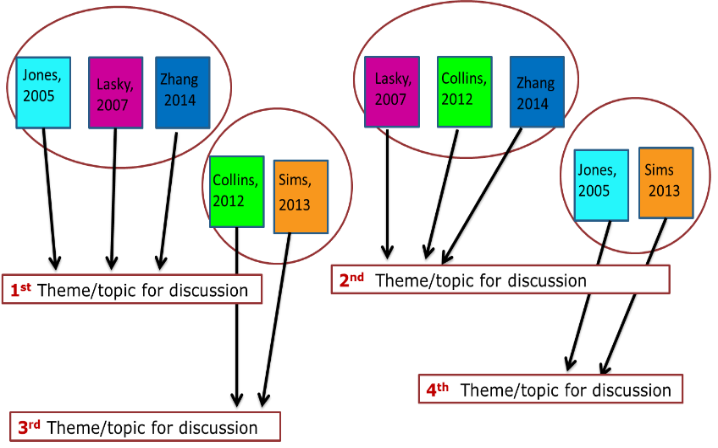

Generally, a literature review requires that you review the scholarly literature and establish the main ideas that have been written about your chosen topic. A literature review does not summarise and evaluate each resource you find (this is what you would do in an annotated bibliography). You are expected to analyse and synthesise or organise common ideas from multiple texts into key themes which are relevant to your topic (see Figure 18.10). You may also be expected to identify gaps in the research.

It is easy to get confused by the terminology used for literature reviews. Some tasks may be described as a systematic literature review when actually the requirement is simpler; to review the literature on the topic but do it in a systematic way. There is a distinct difference (see Table 15.4). As a commencing undergraduate student, it is unlikely you would be expected to complete a systematic literature review as this is a complex and more advanced research task. It is important to check with your lecturer or tutor if you are unsure of the requirements.

| A literature review | A systematic literature review |

|---|---|

| A review that analyses and synthesises the literature on your research topic in a systemic (clear and logical) way. It may be organised: • Conceptually • Chronologically • Methodologically |

A much larger and more complicated research project which follows a clearly defined research protocol or process to remove any reviewer bias. Each step in the search process is documented to ensure it is able to be replicated, repeated or updated. |

When conducting a literature review, use a table or a spreadsheet, if you know how, to organise the information you find. Record the full reference details of the sources as this will save you time later when compiling your reference list (see Table 18.5).

Conclusion

Overall, this chapter has provided an introduction to the types of assignments you can expect to complete at university, as well as outlined some tips and strategies with examples and templates for completing them. First, the chapter investigated essay assignments, including analytical and argumentative essays. It then examined case study assignments, followed by a discussion of the report format. Reflective writing, popular in nursing, education, and human services, was also considered. Finally, the chapter briefly addressed annotated bibliographies and literature reviews. The chapter also has a selection of templates and examples throughout to enhance your understanding and improve the efficacy of your assignment writing skills.

Key points

- Not all assignments at university are the same. Understanding the requirements of different types of assignments will assist in meeting the criteria more effectively.

- There are many different types of assignments. Most will require an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion.

- An essay should have a clear and logical structure and use formal but reader-friendly language.

- Breaking your assignment into manageable chunks makes it easier to approach.

- Effective body paragraphs contain a topic sentence.

- A case study structure is similar to an essay, but you must remember to provide examples from the case or scenario to demonstrate your points.

- The type of report you may be required to write will depend on its purpose and audience. A report requires structured writing and uses headings.

- Reflective writing is popular in many disciplines and is used to explore feelings, experiences, opinions, or events to discover what learning or understanding has occurred. Reflective writing requires more than description. You need to be analytical, consider what has been learnt, and evaluate the impact of this on future actions.

- Annotated bibliographies teach you to research and evaluate sources and systematically organise your notes. They may be part of a larger assignment.

- Literature reviews require you to look across the literature and analyse and synthesise the information you find into themes.

References

Gibbs, G. (1988). Learning by doing: A guide to teaching and learning methods. Further Education Unit, Oxford Brookes University.

Rolfe, G., Freshwater, D., Jasper, M. (2001). Critical reflection in nursing and the helping professions: A user’s guide. Palgrave Macmillan.

Ryan, M. & Ryan, M. (2013). Theorising a model for teaching and assessing reflective learning in higher education. Higher Education Research & Development, 32(2), 244-257. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2012.661704