10.6: Childhood Mental Health

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 24657

Mental health problems can disrupt daily life at home, at school or in the community. Without help, mental health problems can lead to school failure, alcohol or other drug abuse, family discord, violence or even suicide. However, help is available. Talk to your health care provider if you have concerns about your child’s behavior.

Mental health disorders are diagnosed by a qualified professional using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). This is a manual that is used as a standard across the profession for diagnosing and treating mental disorders.42

When You Have a Concern About a Child. What’s in a Label? 43

Children are continually evaluated as they enter and progress through school. If a child is showing a need, they should be assessed by a qualified professional who would make a recommendation or diagnosis of the child and give the type of instruction, resources, accommodations, and support that they should receive.

Ideally, a proper diagnosis or label is extremely beneficial for children who have educational, social, emotional, or developmental needs. Once their difficulty, disorder, or disability is labeled then the child will receive the help they need from parents, educators and any other professionals who will work as a team to meet the student’s individual goals and needs.

However, it’s important to consider that children that are labeled without proper support and accommodations or worse they may be misdiagnosed will have negative consequences. A label can also influence the child’s self-concept, for example, if a child is misdiagnosed as having a learning disability; the child, teachers, and family member interpret their actions through the lens of that label. Labels are powerful and can be good for the child or they can go detrimental for their development all depending on the accuracy of the label and if they are accurately applied.

A team of people who include parents, teachers, and any other support staff will look at the child’s evaluation assessment in a process called an Individual Education Plan (IEP). The team will discuss the diagnosis, recommendations, and the accommodations or help and a decisions will be made regarding what is the best for the child. This is time when parents or caregivers decide if they would like to follow this plan or they can dispute any part of the process. During an IEP, the team is able to voice concerns and questions. Most parents feel empowered when they leave these meetings. They feel as if they are a part of the team and that they know what, when, why, and how their child will be helped.

Childhood Mental Health Disorders

Social and Emotional Disorders

- Phobias

- Anxiety

- Post-Traumatic Stress Syndrome - PTSD

- Obsessive Compulsive Disorder –OCD

- Depression

Developmental Disorders

- Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

- Attention Deficit Disorder (ADHD)

- Pervasive Developmental Disorder (PDD)44

Phobias

When a child who has a phobia (an extreme or irrational fear of or aversion to something) is exposed to the phobic stimulus (the stimuli varies), it almost invariably provokes an immediate anxiety response, which may take the form of a situational bound or situational predisposed panic attack. Children can show effects and characteristics when it comes to specific phobias. The effects of anxiety show up by crying, throwing tantrums, experiencing freezing, or clinging to the parent that they have the most connection with. Related Conditions include anxiety.

Anxiety

Many children have fears and worries, and will feel sad and hopeless from time to time. Strong fears will appear at different times during development. For example, toddlers are often very distressed about being away from their parents, even if they are safe and cared for. Although fears and worries are typical in children, persistent or extreme forms of fear and sadness feelings could be due to anxiety or depression. Because the symptoms primarily involve thoughts and feelings, they are called internalizing disorders.

When children do not outgrow the fears and worries that are typical in young children, or when there are so many fears and worries that interfere with school, home, or play activities, the child may be diagnosed with an anxiety disorder. Examples of different types of anxiety disorders include:

- Being very afraid when away from parents (separation anxiety)

- Having extreme fear about a specific thing or situation, such as dogs, insects, or going to the doctor (phobias)

- Being very afraid of school and other places where there are people (social anxiety)

- Being very worried about the future and about bad things happening (general anxiety)

- Having repeated episodes of sudden, unexpected, intense fear that come with symptoms like heart pounding, having trouble breathing, or feeling dizzy, shaky, or sweaty (panic disorder)

Anxiety may present as fear or worry, but can also make children irritable and angry. Anxiety symptoms can also include trouble sleeping, as well as physical symptoms like fatigue, headaches, or stomachaches. Some anxious children keep their worries to themselves and, thus, the symptoms can be missed.

Related conditions include Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

Post-Traumatic Stress Syndrome (PTSD)

Exposure to traumatic events can have major developmental influences on children. While the majority of children will not develop PTSD after a trauma, best estimates from the literature are that around a third of them will, higher than adult estimates. Some reasons for this could include more limited knowledge about the world, differential coping mechanisms employed, and the fact that children’s reactions to trauma are often highly influenced by how their parents and caregivers react.

The impact of PTSD on children weeks after a trauma, show that up to 90% of children may experience heightened physiological arousal, diffuse anxiety, survivor guilt, and emotional liability. These are all normal reactions and should be understood as such (similar things are seen in adults. Those children still having these symptoms three or four months after a disaster, however, may be in need of further assessment, particularly if they show the following symptoms as well. For older children, warning signs of problematic adjustment include: repetitious play reenacting a part of the disaster; preoccupation with danger or expressed concerns about safety; sleep disturbances and irritability; anger outbursts or aggressiveness; excessive worry about family or friends; school avoidance, particularly involving somatic complaints; behaviors characteristic of younger children; and changes in personality, withdrawal, and loss of interest in activities.46

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

Although a diagnosis of OCD requires only that a person either has obsessions or compulsions, not both, approximately 96% of people experience both. For almost all people with OCD, being exposed to a certain stimuli (internal or external) will then trigger an upsetting or anxiety-causing obsession, which can only be relieved by doing a compulsion. For example, a person touches a doorknob in a public building, which causes an obsessive thought that they will get sick from the germs, which can only be relieved by compulsively washing their hands to an excessive degree. Some of the most common obsessions include unwanted thoughts of harming loved ones, persistent doubts that one has not locked doors or switched off electrical appliances, intrusive thoughts of being contaminated, and morally or sexually repugnant. 47

Depression

Occasionally being sad or feeling hopeless is a part of every child’s life. However, some children feel sad or uninterested in things that they used to enjoy, or feel helpless or hopeless in situations where they could do something to address the situations. When children feel persistent sadness and hopelessness, they may be diagnosed with depression.

Symptoms

We now know that youth who have depression may show signs that are slightly different from the typical adult symptoms of depression. Children who are depressed may complain of feeling sick, refuse to go to school, cling to a parent or caregiver, feel unloved, hopelessness about the future, or worry excessively that a parent may die. Older children and teens may sulk, get into trouble at school, be negative or grouchy, are irritable, indecisive, have trouble concentrating, or feel misunderstood. Because normal behaviors vary from one childhood stage to another, it can be difficult to tell whether a child who shows changes in behavior is just going through a temporary “phase” or is suffering from depression.

Treatment

With medication, psychotherapy, or combined treatment, most youth with depression can be effectively treated. Youth are more likely to respond to treatment if they receive it early in the course of their illness.49

Developmental Disorders

Autism Spectrum Disorder

As introduced in chapter 8, autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a developmental disorder that affects communication and behavior. Although autism can be diagnosed at any age, it is said to be a “developmental disorder” because symptoms generally appear in the first two years of life.

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), a guide created by the American Psychiatric Association used to diagnose mental disorders, people with ASD have:

- Difficulty with communication and interaction with other people

- Restricted interests and repetitive behaviors

- Symptoms that hurt the person’s ability to function properly in school, work, and other areas of life

Autism is known as a “spectrum” disorder because there is wide variation in the type and severity of symptoms people experience. ASD occurs in all ethnic, racial, and economic groups. Although ASD can be a lifelong disorder, treatments and services can improve a person’s symptoms and ability to function. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that all children be screened for autism.

Changes to the diagnosis of ASD

In 2013, a revised version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) was released. This revision changed the way autism is classified and diagnosed. Using the previous version of the DSM, people could be diagnosed with one of several separate conditions:

- Autistic disorder

- Asperger’s’ syndrome

- Pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS)

In the current revised version of the DSM (the DSM-5), these separate conditions have been combined into one diagnosis called “autism spectrum disorder.” Using the DSM-5, for example, people who were previously diagnosed as having Asperger’s syndrome would now be diagnosed as having autism spectrum disorder. Although the “official” diagnosis of ASD has changed, there is nothing wrong with continuing to use terms such as Asperger’s syndrome to describe oneself or to identify with a peer group.

Signs and Symptoms of ASD

People with ASD have difficulty with social communication and interaction, restricted interests, and repetitive behaviors. The list below gives some examples of the types of behaviors that are seen in people diagnosed with ASD. Not all people with ASD will show all behaviors, but most will show several.

Social communication / interaction behaviors may include:

- Making little or inconsistent eye contact

- Tending not to look at or listen to people

- Rarely sharing enjoyment of objects or activities by pointing or showing things to others

- Failing to, or being slow to, respond to someone calling their name or to other verbal attempts to gain attention

- Having difficulties with the back and forth of conversation

- Often talking at length about a favorite subject without noticing that others are not interested or without giving others a chance to respond

- Having facial expressions, movements, and gestures that do not match what is being said

- Having an unusual tone of voice that may sound sing-song or flat and robot-like

- Having trouble understanding another person’s point of view or being unable to predict or understand other people’s actions

Restrictive / repetitive behaviors may include:

- Repeating certain behaviors or having unusual behaviors. For example, repeating words or phrases, a behavior called echolalia

- Having a lasting intense interest in certain topics, such as numbers, details, or facts

- Having overly focused interests, such as with moving objects or parts of objects

- Getting upset by slight changes in a routine

- Being more or less sensitive than other people to sensory input, such as light, noise, clothing, or temperature

People with ASD may also experience sleep problems and irritability. Although people with ASD experience many challenges, they may also have many strengths, including:

- Being able to learn things in detail and remember information for long periods of time

- Being strong visual and auditory learners

- Excelling in math, science, music, or art

Causes and Risk Factors

While scientists don’t know the exact causes of ASD, research suggests that genes can act together with influences from the environment to affect development in ways that lead to ASD. Although scientists are still trying to understand why some people develop ASD and others don’t, some risk factors include:

- Having a sibling with ASD

- Having older parents

- Having certain genetic conditions—people with conditions such as Down syndrome, fragile X syndrome, and Rett syndrome are more likely than others to have ASD

- Very low birth weight

Treatments and Therapies

Treatment for ASD should begin as soon as possible after diagnosis. Early treatment for ASD is important as proper care can reduce individuals’ difficulties while helping them learn new skills and make the most of their strengths.

The wide range of issues facing people with ASD means that there is no single best treatment for ASD. Working closely with a doctor or health care professional is an important part of finding the right treatment program.

A doctor may use medication to treat some symptoms that are common with ASD. With medication, a person with ASD may have fewer problems with:

- Irritability

- Aggression

- Repetitive behavior

- Hyperactivity

- Attention problems

- Anxiety and depression

People with ASD may be referred to doctors who specialize in providing behavioral, psychological, educational, or skill-building interventions. These programs are typically highly structured and intensive and may involve parents, siblings, and other family members. Programs may help people with ASD:

- Learn life-skills necessary to live independently

- Reduce challenging behaviors

- Increase or build upon strengths

- Learn social, communication, and language skills 50

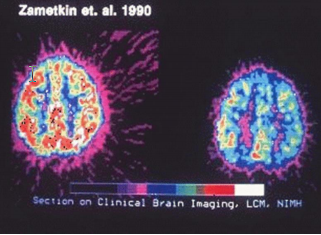

Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (AD/HD)

The exact causes of AD/HD are unknown; however, research has demonstrated that factors that many people associate with the development of AD/HD do not cause the disorder including, minor head injuries, damage to the brain from complications during birth, food allergies, excess sugar intake, too much television, poor schools, or poor parenting. Research has found a number of significant risk factors affecting neurodevelopment and behavior expression. Events such as maternal alcohol and tobacco use that affect the development of the fetal brain can increase the risk for AD/HD. Injuries to the brain from environmental toxins such as lack of iron have also been implicated.

Symptoms

People with AD/HD show a persistent pattern of inattention and/or hyperactivity–impulsivity that interferes with functioning or development:

1. Inattention: Six or more symptoms of inattention for children up to age 16, or five or more for adolescents 17 and older and adults; symptoms of inattention have been present for at least 6 months, and they are inappropriate for developmental level:

- Often fails to give close attention to details or makes careless mistakes in schoolwork, at work, or with other activities.

- Often has trouble holding attention on tasks or play activities.

- Often does not seem to listen when spoken to directly.

- Often does not follow through on instructions and fails to finish schoolwork, chores, or duties in the workplace (e.g., loses focus, side-tracked).

- Often has trouble organizing tasks and activities.

- Often avoids, dislikes, or is reluctant to do tasks that require mental effort over a long period of time (such as schoolwork or homework).

- Often loses things necessary for tasks and activities (e.g. school materials, pencils, books, tools, wallets, keys, paperwork, eyeglasses, mobile telephones).

- Is often easily distracted

- Is often forgetful in daily activities.

2. Hyperactivity and Impulsivity: Six or more symptoms of hyperactivity-impulsivity for children up to age 16, or five or more for adolescents 17 and older and adults; symptoms of hyperactivity-impulsivity have been present for at least 6 months to an extent that is disruptive and inappropriate for the person’s developmental level:

- Often fidgets with or taps hands or feet, or squirms in seat.

- Often leaves seat in situations when remaining seated is expected.

- Often runs about or climbs in situations where it is not appropriate (adolescents or adults may be limited to feeling restless).

- Often unable to play or take part in leisure activities quietly.

- Is often “on the go” acting as if “driven by a motor”.

- Often talks excessively.

- Often blurts out an answer before a question has been completed.

- Often has trouble waiting his/her turn.

- Often interrupts or intrudes on others (e.g., butts into conversations or games)

In addition, the following conditions must be met:

- Several inattentive or hyperactive-impulsive symptoms were present before age 12 years.

- Several symptoms are present in two or more settings, (such as at home, school or work; with friends or relatives; in other activities).

- There is clear evidence that the symptoms interfere with, or reduce the quality of, social, school, or work functioning.

- The symptoms are not better explained by another mental disorder (such as a mood disorder, anxiety disorder, dissociative disorder, or a personality disorder). The symptoms do not happen only during the course of schizophrenia or another psychotic disorder.

Based on the types of symptoms, three kinds (presentations) of AD/HD can occur:

- Combined Presentation: if enough symptoms of both criteria inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity were present for the past 6 months

- Predominantly Inattentive Presentation: if enough symptoms of inattention, but not hyperactivity-impulsivity, were present for the past six months

- Predominantly Hyperactive-Impulsive Presentation: if enough symptoms of hyperactivity-impulsivity, but not inattention, were present for the past six months.

Because symptoms can change over time, the presentation may change over time as well.54 The diagnosis of AD/HD can be made reliably using well-tested diagnostic interview methods. However, as of yet, there is no independent valid test for ADHD.

Among children, AD/HD frequently occurs along with other learning, behavior, or mood problems such as learning disabilities, oppositional defiant disorder, anxiety disorders, and depression.

Treatment

A variety of medications and behavioral interventions are used to treat AD/HD. The most widely used medications are methylphenidate (Ritalin), D-amphetamine, and other amphetamines. These drugs are stimulants that affect the level of the neurotransmitter dopamine at the synapse. Nine out of 10 children improve while taking one of these drugs.

In addition to the well-established treatments described above, some parents and therapists have tried a variety of nutritional interventions to treat AD/HD. A few studies have found that some children benefit from such treatments. Nevertheless, no well-established nutritional interventions have consistently been shown to be effective for treating AD/HD.56

Pervasive Developmental Disorder (PDD) or PPD (NOS) Not Otherwise Specified PDD –NOS

Pervasive developmental disorder (PDD) is a term used to refer to difficulties in socialization and delays in developing communicative skills. This is usually recognized before 3 years of age. A child with PDD may interact in unusual ways with toys, people, or situations, and may engage in repetitive movement. PDD is diagnosed and treatment is similar to ADHA and ASD. In 2013 the DSM- 5 discontinued using this as a diagnosis, however it is still used informally.57

Contributors and Attributions

42. Disease Prevention and Healthy Lifestyles by Judy Baker, Ph.D. is licensed under CC BY-SA (modified by Dawn Rymond)

43. Disease Prevention and Healthy Lifestyles by Judy Baker, Ph.D. is licensed under CC BY-SA (modified by Dawn Rymond)

44. Content by Dawn Rymond is licensed under CC BY 4.0

46. Abnormal Psychology by Lumen Learning references Abnormal Psychology: An e-text! by Dr. Caleb Lack, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA

47. Disease Prevention and Healthy Lifestyles by Judy Baker, Ph.D. is licensed under CC BY-SA

49. Educational Psychology by Kelvin Seifert is licensed under CC BY 3.0

Disease Prevention and Healthy Lifestyles by Judy Baker, Ph.D. is licensed under CC BY-SA

50. Autism Spectrum Disorder by the NIH is in the public domain

54. Symptoms and Diagnosis of ADHD by the CDC is in the public domain

56. Disease Prevention and Healthy Lifestyles by Judy Baker, Ph.D. is licensed under CC BY-SA

57. Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0