Adolescence is a period that begins with puberty and ends with the transition to adulthood (approximately ages 10–18). Physical changes associated with puberty are triggered by hormones. Changes happen at different rates in distinct parts of the brain and increase adolescents’ propensity for risky behavior. Cognitive changes include improvements in complex and abstract thought. Adolescents’ relationships with parents go through a period of redefinition in which many adolescents become more autonomous. Peer relationships are important sources of support, but companionship during adolescence can also promote problem behaviors. Identity formation occurs as adolescents explore and commit to different roles and ideological positions. Because so much is happening in these years, psychologists have focused a great deal of attention on the period of adolescence.

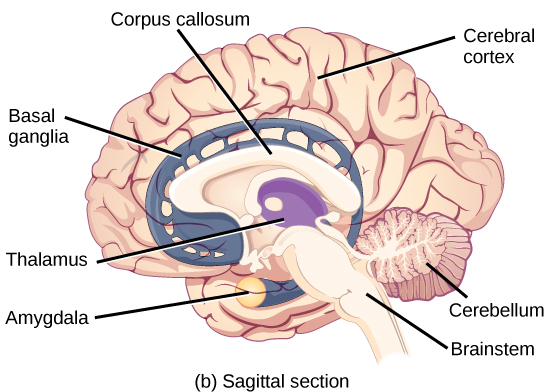

The Adolescent Brain

The brain undergoes dramatic changes during adolescence. Although it does not get larger, it matures by becoming more interconnected and specialized. The myelination and development of connections between neurons continues. This results in an increase in the white matter of the brain, and allows the adolescent to make significant improvements in their thinking and processing skills. Different brain areas become myelinated at different times. For example, the brain’s language areas undergo myelination during the first 13 years. Completed insulation of the axons consolidates these language skills, but makes it more difficult to learn a second language. With greater myelination, however, comes diminished plasticity as a myelin coating inhibits the growth of new connections.

Even as the connections between neurons are strengthened, synaptic pruning occurs more than during childhood as the brain adapts to changes in the environment. This synaptic pruning causes the gray matter of the brain, or the cortex, to become thinner but more efficient. The corpus callosum, which connects the two hemispheres, continues to thicken allowing for stronger connections between brain areas. Additionally, the hippocampus becomes more strongly connected to the frontal lobes, allowing for greater integration of memory and experiences into our decision making.

Figure 1. The Limbic System.

The limbic system, which regulates emotion and reward, is linked to the hormonal changes that occur at puberty. The limbic system is also related to novelty seeking and a shift toward interacting with peers. In contrast, the prefrontal cortex which is involved in the control of impulses, organization, planning, and making good decisions, does not fully develop until the mid-20s. According to Giedd (2015) the significant aspect of the later developing prefrontal cortex and early development of the limbic system is the “mismatch” in timing between the two. The approximately ten years that separates the development of these two brain areas can result in risky behavior, poor decision making, and weak emotional control for the adolescent. When puberty begins earlier, this mismatch extends even further.

Teens often take more risks than adults and according to research, it is because they weigh risks and rewards differently than adults do. For adolescents, the brain’s sensitivity to the neurotransmitter dopamine peaks, and dopamine is involved in reward circuits so the possible rewards outweigh the risks. Adolescents respond especially strongly to social rewards during activities, and they prefer the company of others their same age. In addition to dopamine, the adolescent brain is affected by oxytocin which facilitates bonding and makes social connections more rewarding. With both dopamine and oxytocin engaged, it is no wonder that adolescents seek peers and excitement in their lives that could end up actually harming them.

Because of all the changes that occur in the adolescent brain, the chances for abnormal development can occur, including mental illness. In fact, 50% of the mental illness occurs by the age 14 and 75% occurs by age 24. Additionally, during this period of development the adolescent brain is especially vulnerable to damage from drug exposure. For example, repeated exposure to marijuana can affect cellular activity in the endocannabinoid system. Consequently, adolescents are more sensitive to the effects of repeated marijuana exposure.

However, researchers have also focused on the highly adaptive qualities of the adolescent brain which allow the adolescent to move away from the family towards the outside world., Novelty seeking and risk-taking can generate positive outcomes including meeting new people and seeking out new situations. Separating from the family and moving into new relationships and different experiences are actually quite adaptive for society.

Adolescent Sleep

According to the National Sleep Foundation (NSF) (2016), adolescents need about 8 to 10 hours of sleep each night to function best. The most recent Sleep in America poll in 2006 indicated that adolescents between sixth and twelfth grade were not getting the recommended amount of sleep. On average adolescents only received 7 ½ hours of sleep per night on school nights with younger adolescents getting more than older ones (8.4 hours for sixth graders and only 6.9 hours for those in twelfth grade). For older adolescents, only about one in ten (9%) get an optimal amount of sleep, and they are more likely to experience negative consequences the following day. These include feeling too tired or sleepy, being cranky or irritable, falling asleep in school, having a depressed mood, and drinking caffeinated beverages (NSF, 2016). Additionally, they are at risk for substance abuse, car crashes, poor academic performance, obesity, and a weakened immune system.

Why don’t adolescents get adequate sleep? In addition to known environmental and social factors, including work, homework, media, technology, and socializing, the adolescent brain is also a factor. As adolescents go through puberty, their circadian rhythms change and push back their sleep time until later in the evening. This biological change not only keeps adolescents awake at night, but it also makes it difficult for them to get up in the morning. When they are awake too early, their brains do not function optimally. Impairments are noted in attention, behavior, and academic achievement, while increases in tardiness and absenteeism are also demonstrated.

Adolescent Sexual Activity

By about age ten or eleven, most children experience increased sexual attraction to others that affects their social life, both in school and out.

Adolescent Pregnancy

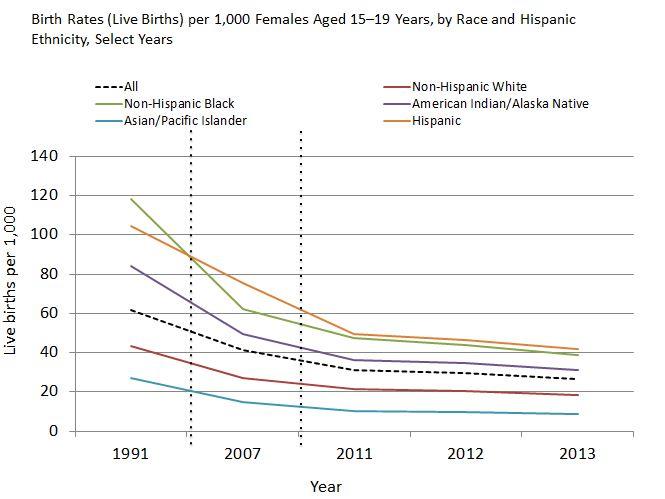

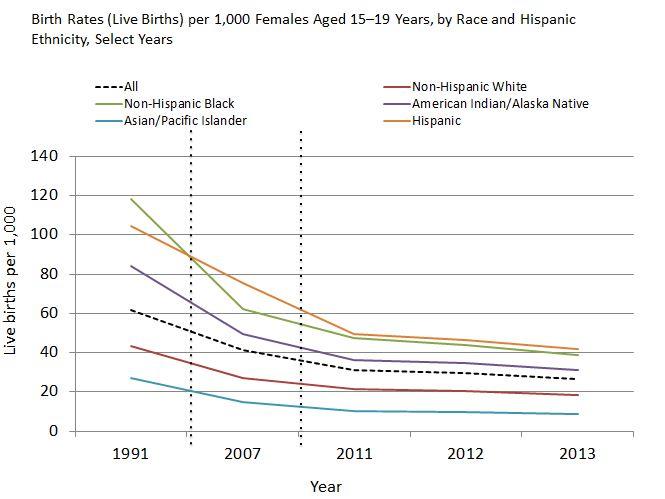

Figure 2. Teenage birth rates have been declining steadily since the 1990s, with a particular drop around 2007 for all groups.

Although adolescent pregnancy rates have declined since 1991, teenage birth rates in the United States are higher than most developed countries. In 2014 females aged 15–19 years experienced a birth rate of 24.2 per 1,000 women. This is a drop of 9% from 2013. Birth rates fell 11% for those aged 15–17 years and 7% for 18–19 year-olds. It appears that adolescents seem to be less sexually active than in previous years, and those who are sexually active seem to be using birth control. Figure 6.6 shows the birth rates (live births) per 1,000 females aged 15– 19 years for all races and Hispanic ethnicity in the United States, 1991, 2007, 2011, 2012, & 2013.

Risk Factors for Adolescent Pregnancy

Miller, Benson, and Galbraith (2001) found that parent/child closeness, parental supervision, and parents’ values against teen intercourse (or unprotected intercourse) decreased the risk of adolescent pregnancy. In contrast, residing in disorganized/dangerous neighborhoods, living in a lower SES family, living with a single parent, having older sexually active siblings or pregnant/parenting teenage sisters, early puberty, and being a victim of sexual abuse place adolescents at an increased risk of adolescent pregnancy.

Consequences of Adolescent Pregnancy

After the child is born life can be difficult for a teenage mother. Teenagers who have a child before age 18 years of age are less likely to graduate from high school. Without a high school degree, job prospects are limited and economic independence is difficult. Teen mothers are more likely to live in poverty, and more than 75% of all unmarried teen mothers receive public assistance within 5 years of the birth of their first child. Approximately, 64% of children born to an unmarried teenage high-school dropout live in poverty. Further, a child born to a teenage mother is 50% more likely to repeat a grade in school and is more likely to perform poorly on standardized tests and drop out before finishing high school. Research analyzing the age that men father their first child and how far they complete their education have been summarized by the Pew Research Center (2015) and reflect the research for females. Among dads ages 22 to 44, 70% of those with less than a high school diploma say they fathered their first child before the age of 25. In comparison, less than half (45%) of fathers with some college experience became dads by that age. Additionally, becoming a young father occurs much less for those with a bachelor’s degree or higher as just 14% had their first child prior to age 25. Like men, women with more education are likely to be older when they become mothers.

Piaget’s Formal Operational Stage

During the formal operational stage, adolescents are able to understand abstract principles which have no physical reference. They can now contemplate such abstract constructs as beauty, love, freedom, and morality. The adolescent is no longer limited by what can be directly seen or heard. Additionally, while younger children solve problems through trial and error, adolescents demonstrate hypothetical-deductive reasoning, which is developing hypotheses based on what might logically occur. They are able to think about all the possibilities in a situation beforehand, and then test them systematically. Now they are able to engage in true scientific thinking. Formal operational thinking also involves accepting hypothetical situations. Adolescents understand the concept of transitivity, which means that a relationship between two elements is carried over to other elements logically related to the first two, such as if A<B and B<C, then A<C. For example, when asked: If Maria is shorter than Alicia and Alicia is shorter than Caitlyn, who is the shortest? Adolescents are able to answer the question correctly as they understand the transitivity involved.

According to Piaget, most people attain some degree of formal operational thinking, but use formal operations primarily in the areas of their strongest interest. In fact, most adults do not regularly demonstrate formal operational thought, and in small villages and tribal communities, it is barely used at all. A possible explanation is that an individual’s thinking has not been sufficiently challenged to demonstrate formal operational thought in all areas.

Adolescent Egocentrism

Once adolescents can understand abstract thoughts, they enter a world of hypothetical possibilities and demonstrate egocentrism or a heightened self-focus. The egocentricity comes from attributing unlimited power to their own thoughts. Piaget believed it was not until adolescents took on adult roles that they would be able to learn the limits to their own thoughts.

David Elkind (1967) expanded on the concept of Piaget’s adolescent egocentricity. Elkind theorized that the physiological changes that occur during adolescence result in adolescents being primarily concerned with themselves. Additionally, since adolescents fail to differentiate between what others are thinking and their own thoughts, they believe that others are just as fascinated with their behavior and appearance. This belief results in the adolescent anticipating the reactions of others, and consequently constructing an imaginary audience. “The imaginary audience is the adolescent’s belief that those around them are as concerned and focused on their appearance as they themselves are” (p. 441). Elkind thought that the imaginary audience contributed to the self-consciousness that occurs during early adolescence. The desire for privacy and reluctance to share personal information may be a further reaction to feeling under constant observation by others.

Another important consequence of adolescent egocentrism is the personal fable or a belief that one is unique, special, and invulnerable to harm. Elkind (1967) explains that because adolescents feel so important to others (imaginary audience) they regard themselves and their feelings as being special and unique. Adolescents believe that only they have experienced strong and diverse emotions, and therefore others could never understand how they feel. This uniqueness in one’s emotional experiences reinforces the adolescent’s belief of invulnerability, especially to death. Adolescents will engage in risky behaviors, such as drinking and driving or unprotected sex, and feel they will not suffer any negative consequences. Elkind believed that adolescent egocentricity emerged in early adolescence and declined in middle adolescence, however, recent research has also identified egocentricity in late adolescence.

Consequences of Formal Operational Thought

As adolescents are now able to think abstractly and hypothetically, they exhibit many new ways of reflecting on information. For example, they demonstrate greater introspection or thinking about one’s thoughts and feelings. They begin to imagine how the world could be which leads them to become idealistic or insisting upon high standards of behavior. Because of their idealism, they may become critical of others, especially adults in their life. Additionally, adolescents can demonstrate hypocrisy, or pretend to be what they are not. Since they are able to recognize what others expect of them, they will conform to those expectations for their emotions and behavior seemingly hypocritical to themselves.

Information Processing

Executive functions, such as attention, increases in working memory, and cognitive flexibility have been steadily improving since early childhood. Studies have found that executive function is very competent in adolescence. However, self-regulation, or the ability to control impulses, may still fail. A failure in self- regulation is especially true when there is high stress or high demand on mental functions. While high stress or demand may tax even an adult’s self-regulatory abilities, neurological changes in the adolescent brain may make teens particularly prone to more risky decision making under these conditions.

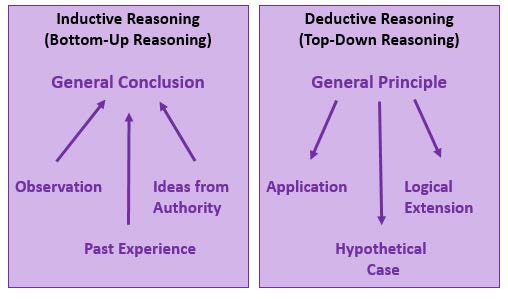

Inductive and Deductive Reasoning

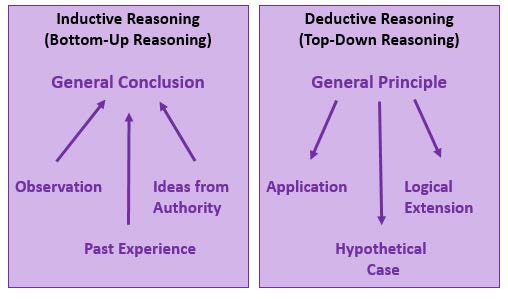

Figure 3. Inductive reasoning and deductive reasoning visualized.

Inductive reasoning emerges in childhood, and is a type of reasoning that is sometimes characterized as “bottom-up- processing” in which specific observations, or specific comments from those in authority, may be used to draw general conclusions. However, in inductive reasoning the veracity of the information that created the general conclusion does not guarantee the accuracy of that conclusion. For instance, a child who has only observed thunder on summer days may conclude that it only thunders in the summer.

In contrast, deductive reasoning, sometimes called “top-down-processing”, emerges in adolescence. This type of reasoning starts with some overarching principle, and based on this propose specific conclusions. Deductive reasoning guarantees a truthful conclusion if the premises on which it is based are accurate.

Intuitive versus Analytic Thinking: Cognitive psychologists often refer to intuitive and analytic thought as the Dual-Process Model; the notion that humans have two distinct networks for processing information.Intuitive thought is automatic, unconscious, and fast, and it is more experiential and emotional. In contrast, Analytic thought is deliberate, conscious, and rational. While these systems interact, they are distinct. Intuitive thought is easier and more commonly used in everyday life. It is also more commonly used by children and teens than by adults. The quickness of adolescent thought, along with the maturation of the limbic system, may make teens more prone to emotional intuitive thinking than adults.

Erikson: Identity vs. Role Confusion

Erikson believed that the primary psychosocial task of adolescence was establishing an identity. Teens struggle with the question “Who am I?” This includes questions regarding their appearance, vocational choices and career aspirations, education, relationships, sexuality, political and social views, personality, and interests. Erikson saw this as a period of confusion and experimentation regarding identity and one’s life path. During adolescence we experience psychological moratorium, where teens put on hold commitment to an identity while exploring the options. The culmination of this exploration is a more coherent view of oneself. Those who are unsuccessful at resolving this stage may either withdraw further into social isolation or become lost in the crowd. However, more recent research, suggests that few leave this age period with identity achievement and that most identity formation occurs during young adulthood.

Developmental psychologists have researched several different areas of identity development and some of the main areas include:

- Religious identity: The religious views of teens are often similar to that of their families. Most teens may question specific customs, practices, or ideas in the faith of their parents, but few completely reject the religion of their families.

- Political identity: The political ideology of teens is also influenced by their parents’ political beliefs. A new trend in the 21st century is a decrease in party affiliation among adults. Many adults do not align themselves with either the democratic or republican party, but view themselves as more of an “independent”. Their teenage children are often following suit or become more apolitical.

- Vocational identity: While adolescents in earlier generations envisioned themselves as working in a particular job, and often worked as an apprentice or part-time in such occupations as teenagers, this is rarely the case today. Vocational identity takes longer to develop, as most of today’s occupations require specific skills and knowledge that will require additional education or are acquired on the job itself. In addition, many of the jobs held by teens are not in occupations that most teens will seek as adults.

- Gender identity: This is also becoming an increasingly prolonged task as attitudes and norms regarding gender keep changing. The roles appropriate for males and females are evolving. Some teens may foreclose on a gender identity as a way of dealing with this uncertainty, and they may adopt more stereotypic male or female roles.

- Ethnic identity refers to how people come to terms with who they are based on their ethnic or racial ancestry. “The task of ethnic identity formation involves sorting out and resolving positive and negative feelings and attitudes about one’s own ethnic group and about other groups and identifying one’s place in relation to both” (p. 119). When groups differ in status in a culture, those from the non- dominant group have to be cognizant of the customs and values of those from the dominant culture. The reverse is rarely the case. This makes ethnic identity far less salient for members of the dominant culture. In the United States, those of European ancestry engage in less exploration of ethnic identity, than do those of non-European ancestry. However, according to the U.S. Census (2012) more than 40% of Americans under the age of 18 are from ethnic minorities. For many ethnic minority teens, discovering one’s ethnic identity is an important part of identity formation.

Phinney’s model of ethnic identity formation is based on Erikson’s and Marcia’s model of identity formation., Through the process of exploration and commitment, individuals come to understand and create an ethnic identity. Phinney suggests three stages or statuses with regard to ethnic identity:

- Unexamined Ethnic Identity: Adolescents and adults who have not been exposed to ethnic identity issues may be in the first stage, unexamined ethnic identity. This is often characterized by a preference for the dominant culture, or where the individual has given little thought to the question of their ethnic heritage. This is similar to diffusion in Marcia’s model of identity. Included in this group are also those who have adopted the ethnicity of their parents and other family members with little thought about the issues themselves, similar to Marcia’s foreclosure status.

- Ethnic Identity Search: Adolescents and adults who are exploring the customs, culture, and history of their ethnic group are in the ethnic identity search stage, similar to Marcia’s moratorium status. Often some event “awakens” a teen or adult to their ethnic group; either personal experience with prejudice, a highly profiled case in the media, or even a more positive event that recognizes the contribution of someone from the individual’s ethnic group. Teens and adults in this stage will immerse themselves in their ethnic culture. For some, “it may lead to a rejection of the values of the dominant culture” (p. 503).

- Achieved Ethnic Identity: Those who have actively explored their culture are likely to have a deeper appreciation and understanding of their ethnic heritage, leading to progress toward an achieved ethnic identity. An achieved ethnic identity does not necessarily imply that the individual is highly involved in the customs and values of their ethnic culture. One can be confident in their ethnic identity without wanting to maintain the language or other customs.

The development of ethnic identity takes time, with about 25% of tenth graders from ethnic minority backgrounds having explored and resolved the issues. The more ethnically homogeneous the high school, the less identity exploration and achievement. Moreover, even in more ethnically diverse high schools, teens tend to spend more time with their own group, reducing exposure to other ethnicities. This may explain why, for many, college becomes the time of ethnic identity exploration. “[The] transition to college may serve as a consciousness-raising experience that triggers exploration.”

It is also important to note that those who do achieve ethnic identity may periodically reexamine the issues of ethnicity. This cycling between exploration and achievement is common not only for ethnic identity formation but in other aspects of identity development.

Bicultural/Multiracial Identity

Ethnic minorities must wrestle with the question of how, and to what extent, they will identify with the culture of the surrounding society and with the culture of their family. Phinney (2006) suggests that people may handle it in different ways. Some may keep the identities separate, others may combine them in some way, while others may reject some of them. Bicultural identity means the individual sees himself or herself as part of both the ethnic minority group and the larger society. Those who are multiracial, that is whose parents come from two or more ethnic or racial groups, have a more challenging task. In some cases their appearance may be ambiguous. This can lead to others constantly asking them to categorize themselves. Phinney (2006) notes that the process of identity formation may start earlier and take longer to accomplish in those who are not mono-racial.

Parents and Teens: Autonomy and Attachment

While most adolescents get along with their parents, they do spend less time with them. This decrease in the time spent with families may be a reflection of a teenager’s greater desire for independence or autonomy. It can be difficult for many parents to deal with this desire for autonomy. However, it is likely adaptive for teenagers to increasingly distance themselves and establish relationships outside of their families in preparation for adulthood. This means that both parents and teenagers need to strike a balance between autonomy, while still maintaining close and supportive familial relationships.

Children in middle and late childhood are increasingly granted greater freedom regarding moment-to-moment decision making. This continues in adolescence, as teens are demanding greater control in decisions that affect their daily lives. This can increase conflict between parents and their teenagers. For many adolescents, this conflict centers on chores, homework, curfew, dating, and personal appearance. These are all things many teens believe they should manage that parents previously had considerable control over. Teens report more conflict with their mothers, as many mothers believe they should still have some control over many of these areas, yet often report their mothers to be more encouraging and supportive. As teens grow older, more compromise is reached between parents and teenagers. Parents are more controlling of daughters, especially early-maturing girls, than they are sons. In addition, culture and ethnicity also play a role in how restrictive parents are with the daily lives of their children.

Having supportive, less conflict-ridden relationships with parents also benefits teenagers. Research on attachment in adolescence find that teens who are still securely attached to their parents have less emotional problems, are less likely to engage in drug abuse and other criminal behaviors, and have more positive peer relationships.