5.4: Adversity and Toxic Stress

- Page ID

- 139791

Overview of Impacts of Adversity and Toxic Stress

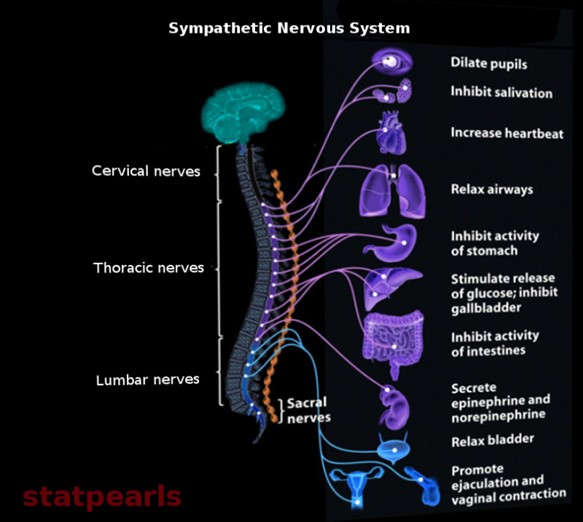

Stress is a term commonly used to describe the response to the demands encountered on a daily basis throughout one’s lifetime, and it is related to both positive experiences and negative experiences. Stressors are agents that produce stress. Stressors may be physical, emotional, environmental or theoretical, and all may equally affect the body’s stress response. The stress response, also known as the “fight or flight” response comprises the physiologic changes that occur with any encounter of stress or perceived stress to the individual (Cannon, 2013; Selye, 1976). This stress response is a result of stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system resulting in a cascade of neuro-endocrine-immune responses that include an increase in respirations, heart rate, blood pressure, and overall oxygen consumption (Chrousos & Gold, 1992; Dusek & Benson, 2009). As Figure# shows, the sympathetic nervous system is composed of many pathways that perform a variety of functions on various organ systems. The main overall end effect of the sympathetic nervous system is to prepare the body for physical activity一a whole-body reaction affecting many organ systems throughout the body (McCorry, 2007). In most situations, the physiologic changes associated with the stress response are short lived, with the body returning to its baseline state when the stressor is removed. [1] [2]

While some degree of stress and adversity is normal and an essential part of human development, exposure to frequent and prolonged adversity, especially in the absence of protective factors, can result in toxic stress. Childhood toxic stress is severe, prolonged, or repetitive adversity with a lack of the necessary nurturance or support of a caregiver to prevent an abnormal stress response (National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2014). This abnormal stress response consists of a derangement of the neuro-endocrine-immune response resulting in prolonged cortisol activation and a persistent inflammatory state, with failure of the body to normalize these changes after the stressor is removed (Johnson, Riley, Granger & Riis, 2013; Wolf, Miller & Chen, 2008). Children who experience early life toxic stress are at risk of long-term adverse health effects that may not manifest until adulthood. These adverse health effects include maladaptive coping skills, poor stress management, unhealthy lifestyles, mental illness and physical disease (Boyce et al., 2021; Garner et al., 2012; Johnson, Riley, Granger & Riis, 2013). [4] [5]

There are three general types of responses to stress: [5]

- Positive stress response. A positive stress response is a normal stress response and is essential for the growth and development of a child. Positive stress responses are infrequent, short-lived, and mild. The child is supported through this stressful event with strong social and emotional buffers such as reassurance and parental protection. The child gains motivation and resilience from every positive stress response, and the biochemical reactions that occur with such a stressful event return to baseline (National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2014). Examples include meeting new people or learning a new task.

- Tolerable stress response. Tolerable stress responses are more severe, frequent or sustained. The body responds to a greater degree compared to the positive stress response, and these biochemical responses have the potential to negatively affect brain architecture. Examples include divorce or the death of a loved one. In tolerable stress responses, once the adversity has passed, the brain and organs can recover fully if the child is protected with responsive relationships and strong social and emotional support. Therefore, an important feature of the tolerable stress response is the role of caregivers. The risks for short-term and long-term psychological impact can be reduced if children have protective relationships that support them to cope with these events (Shonkoff & Levitt, 2010). [6]

- Toxic stress response. Toxic stress results in prolonged activation of the stress response, with a failure of the body to recover fully. It differs from a normal stress response in that there is a lack of caregiver support, reassurance, or emotional attachments. The insufficient caretaker support prevents the buffering of the stress response or the return of the body to baseline function. Examples of toxic stress include abuse, neglect, extreme poverty, violence, household dysfunction, and food scarcity. Caretakers with substance abuse or mental health conditions also predispose a child to a toxic stress response. Exposure to less severe yet chronic, ongoing daily stressors can also be toxic to children (Yates, 2007). Early life toxic stressors increase one’s vulnerability to maladaptive health outcomes such as an unhealthy lifestyle, socioeconomic inequity, and poor health; however, these stressors do not solely predict or determine an adult’s behavior or health (Odgers & Jaffee, 2013; Shonkoff, Boyce & McEwen, 2009).

[1] Franke (2014). Toxic stress: effects, prevention and treatment. Children, 1(3), 390-402. CC by 4.0

[2] Alshak & Das (2021). Neuroanatomy, sympathetic nervous system. StatPearls. CC by 4.0

[3] Image from Alshak & Das (2021). Neuroanatomy, sympathetic nervous system. StatPearls. CC by 4.0

[4] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). Adverse childhood experiences prevention strategy. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

[5] Franke (2014). Toxic stress: effects, prevention and treatment. Children, 1(3), 390-402. CC by 4.0

[2] Branco & Linhares (2018). The toxic stress and its impact on development in the Shonkoff’s Ecobiodevelopmental Theoretical approach. Estudos de Psicologia, 35, 89-98. CC by 4.0