8.6.1: Imitation

- Page ID

- 140100

Infant Imitation

Imitation of others’ behavior is considered a central means of learning, specifically for social cognition and the learning of cultural norms (Goertz et al., 2011; Kugiumutzakis & Trevarthen, 2015; Meltzoff & Marshall, 2018). Imitation has been defined in numerous ways, emphasizing the matching of either the form of movements, the outcomes, or the intentions of an action. The often cited findings from Meltzoff and Moore (1977; 1983), that newborns imitate adult facial expressions, has been called into question. Recent research has been unable to replicate their findings and has pointed out critical weaknesses and limitations in those early newborn imitation studies (Kennedy-Costantini et al., 2017; Oostenbroek et al., 2016; Oostenbroek et al., 2018; Slaughter, 2021).[1]

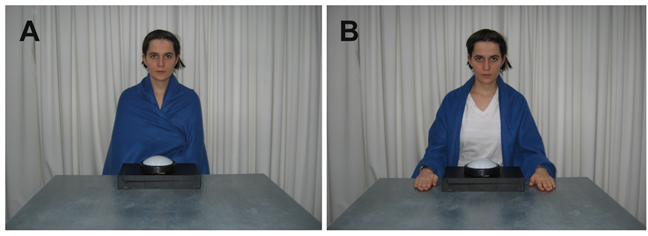

While newborn imitation continues to be debated, it is clear that imitation plays a role in learning for older infants and toddlers. It has been found that 12 to 18 month-olds learn one to two novel actions every day, merely by observing others around them (Barr & Hayne, 2003). Rather than imitating everything and everyone, however, infants tend to be selective in their imitative behavior, a tendency that is present beginning around 12 months of age (Schwier et al., 2006; Zmyj, Daum & Aschersleben, 2009). For example, in one study researchers presented a novel head action to two groups of 14-month-olds whereby the model illuminated a light-box with her forehead by sitting in a chair and leaning forward until her head pressed on the light-box (Gergely, Bekkering & Király, 2002). While one group of infants observed the unusual head action with the model freely resting her hands next to the light box (hands-free condition), the other group observed a demonstration of the identical head action, but the model had her hands occupied by holding a blanket wrapped around her torso (hands-occupied condition). Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) illustrates the two conditions. The majority (69%) of infants in the hands-free condition imitated this novel action of using their forehead to turn on the light-box, whereas only 21% of infants did so in the hands-occupied condition. The authors argued the results suggest that infants inferred that the model must have had good reasons to freely choose to perform the unusual action in the hands-free condition, whereas the model would have used her hands in the hands-occupied condition if she was not using her hands to hold the blanket. As a result, while imitation can be a great way to learn, the imitation process for infants and toddlers is complex as they consider various factors that may influence what actions of adults are rational or logical before imitating. [3] [4]

As imitation is one way infants and toddlers learn about the world, caregivers can support cognitive development through imitation by including infants and toddlers in everyday care routines and by demonstrating more complex actions during play and social interactions. Care routines (e.g., diapering, meal time, etc.,) can sometimes become more like adult-driven chores if caregivers quickly rush through with the goal of completion. However, care routines often involve complex actions that can be rich learning opportunities for young children to watch, imitate and learn from. For example, the care routine of meal time involves motor movements to support pouring, scooping, holding, passing, etc., and also involves the learning of social patterns such as waiting, turn taking, manners etc.,. These motor actions and social patterns may be challenging for young toddlers, but are important as they practice these skills and are able to participate more in the meal time routine. Instead of preparing individual plates ahead of time and out of the sight of the children, plates can be prepared and shared in their presence. A family-style meal presentation where food and drinks are served at the table with toddlers, allows for them to be able to watch, imitate and learn from the meal time routine. Additionally, during play and social interactions, caregivers who are engaged with infants and toddlers and demonstrate different ways to use and play with materials encourage infants and toddlers to imitate similar actions as they learn about how the world works.

[1] Paukner et al., (2017). Testing the arousal hypothesis of neonatal imitation in infant rhesus macaques. PLoS One, 12(6), e0178864. CC by 4.0

[2] Image by HeatherDawnKemp on Pixabay.

[3] Gellén & Buttelmann (2017). Fourteen-month-olds adapt their imitative behavior in light of a model’s constraints. Child Development Research. CC by 4.0

[4] Beisert et al., (2012). Rethinking ‘rational imitation in 14-month-old infants: A perceptual distraction approach. PloS One, 7(3), e32563. CC by 4.0

[5] Image from Beisert et al., (2012). Rethinking ‘rational imitation in 14-month-old infants: A perceptual distraction approach. PloS One, 7(3), e32563. CC by 4.0