9.2: Jean Piaget

- Page ID

- 139915

Overview of Jean Piaget

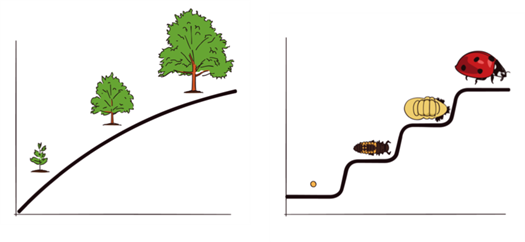

Jean Piaget (1896-1980) was a renowned psychologist of the 20th century and a pioneer in developmental psychology. Piaget did not accept the prevailing theory that knowledge was innate. Instead, he believed a child’s knowledge and understanding of the world developed over time, through the child’s interactions with the world. By observing that interaction, Piaget was able to perceive how children created schemas (mental ways to organize information) that shaped their perceptions, cognitions, and judgment of the world. Just as almost all babies learn to roll over before they learn to sit up by themselves, Piaget believed that children gain their cognitive ability in a developmental order. These insights—that children at different ages think in fundamentally different ways—led to Piaget’s stage theory of cognitive development. As a stage theorist, Piaget believed cognitive change occurred in distinct stages with a fixed-order, rather than continuous development that argued for a more gradual continuous process (see Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) for an analogy). Despite various limitations, Piaget's theory of cognitive development is one of the most enduring theories in psychology. [2]

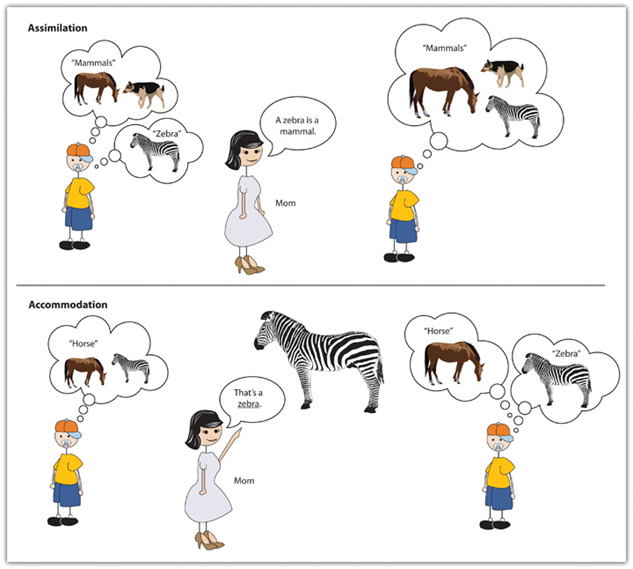

Piaget believed that children do not just passively learn but actively try to make sense of their worlds. He argued that, as they learn and mature, children develop schemas that help them remember, organize, and respond to information. Furthermore, Piaget thought that when children experience new things, they attempt to reconcile the new knowledge with existing schemas through methods that he called assimilation and accommodation. [4]

When children apply assimilation, they use already developed schemas to understand new information. If children have learned a schema for horses, then they might call the striped animal they see at the zoo a horse rather than a zebra. In this case, children fit the existing schema (knowledge that defines a horse separate from other animals) to the new experience (a zebra) because zebras fit the basic schema of a horse. Accommodation, on the other hand, involves learning new information, and thus changing/updating the schema. When a mother says, “No, honey, that’s a zebra, not a horse,” the child may adapt the schema to fit the new experience, learning that there are different types of four-legged animals, only one of which is a horse and that zebras are unique because of their black and white stripes.

Piaget’s Stages of Cognitive Development

Over his lifetime, Piaget contributed significantly to the study of cognitive development in children. Piaget’s most important contribution to understanding cognitive development, and the fundamental aspect of his theory, was the idea that development occurs in unique and distinct stages, with each stage occurring at a specific time, in a sequential manner, and in a way that allows the child to think about the world using new capacities. Piaget classified children’s cognitive development into four sequential stages: (1) The sensorimotor period from birth to 24 months, (2) the pre-operations period between the approximate ages of two and seven years old, (3) the concrete operational period that begins around age seven and continues through about 11 years old, and (4) the formal operations period that begins around age 11 and continues through adolescence. [2]

|

Stage |

Approximate age range |

Characteristics |

Stage attainments |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Sensorimotor |

Birth to about 2 years |

The child experiences the world through the fundamental senses of seeing, hearing, touching, and tasting. |

Object permanence |

|

Preoperational |

2 to 7 years |

Children acquire the ability to internally represent the world through language and mental imagery. They also start to see the world from other people’s perspectives. |

Theory of mind; rapid increase in language ability |

|

Concrete operational |

7 to 11 years |

Children become able to think logically. They can perform operations on objects, but only those which are real ("concrete"), not those which are abstract. |

Conservation |

| Formal operational | 11 years to adulthood | Adolescents can think systematically, can reason about abstract concepts, and can understand ethics and scientific reasoning. | Abstract logic |

As this text is about infants and toddlers, we will primarily focus on the first stage, the sensorimotor stage, which includes children between the ages of 0 to 2 years. During the sensorimotor stage, children use their senses and motor capabilities to understand the world. In fact, infants’ use of their senses to perceive the world is so central to their understanding that whenever infants do not directly perceive objects, as far as they are concerned, the objects do not exist. Piaget found, for instance, that if he first interested infants in a toy and then covered the toy with a blanket, infants who were younger than 6 months of age would act as if the toy had disappeared completely—they never tried to find it under the blanket but would nevertheless smile and reach for it when the blanket was removed. Piaget found that it was not until about 8 months that the infants realized that the object was merely covered and not gone. Piaget used the term object permanence to refer to the child’s ability to know that an object exists even when the object cannot be perceived. [4]

Sensorimotor Substages

The sensorimotor period begins at birth and continues through the child’s first two years. It focuses on the development of schemes as infants’ sensory and motor systems interact with the world. There are six substages within the sensorimotor period.

|

Sensorimotor Substage |

Age |

|---|---|

|

Substage 1: Simple Reflexes |

Birth to 1 month |

|

Substage 2: Primary Circular Reactions |

1 to 4 months |

|

Substage 3: Secondary Circular Reactions |

4 to 8 months |

|

Substage 4: Coordination of Circular Reactions |

8 to 12 months |

|

Substage 5: Tertiary Circular Reactions |

12 to 18 months |

|

Substage 6: Internalization of Schemes and Early Representational Thought |

18 months to 2 years |

Stage 1 lasts from birth until around 1 month of age. At this first stage, learning by experiencing the world is largely driven by inborn motor and sensory reflexes, like the sucking and palmar reflexes. With the palmar reflex, when something is placed in the palm of an infant, their involuntary reflex is to close their fingers around it and cling on to it. By doing so, the infant is able to experience shape, texture, temperature, weight, etc.,. The palmar reflex typically disappears by six months of age (Anekar & Bordoni, 2020). At this stage, Piaget proposed that learning about the world is not primarily voluntary, instead, infants begin to encounter the world as a result of their inborn reflexes. [2] [8]

Stage 2, which occurs approximately between 1 and 4 months, includes the primary circular reaction in which an infant happens to experience an event and then attempts to repeat the action. The infant begins to discriminate between objects and adjust responses accordingly as reflexes are replaced with voluntary movements. An infant may accidentally engage in a behavior and find it interesting, such as making a vocalization. This interest motivates them to try to do it again and helps the infant learn a new behavior that originally occurred by chance. At first, most actions have to do with the body, but in the months to come, will be directed more toward objects.[2] [8]

Stage 3, which takes place between 4-8 months, involves secondary circular reactions when an infant repeats an action with a specific, desired consequence or to achieve an unrelated consequence. The infant becomes more and more actively engaged in the outside world and takes delight in being able to make things purposely happen on their own. Repeated motion brings particular interest, for example, as the infant is able to bang two things together or when sticking out their tongue leads to their parents laughing. [2] [8]

Stage 4, which occurs approximately between 8 and 12 months, comprises the use of familiar means to obtain ends. It entails deliberate planning of steps to meet a goal or objective. The infant can engage in behaviors that others perform and anticipate upcoming events. Perhaps because of continued maturation of the prefrontal cortex, the infant becomes capable of having a thought and carrying out a planned, goal-directed activity such as seeking a toy that has rolled under the couch. The object continues to exist in the infant’s mind even when out of sight and the infant now is capable of making attempts to retrieve it. [2] [8]

Stage 5, which takes place between 12 to 18 months of age, is a tertiary circular reaction in which an infant experiments with their environment using the properties of one object to manipulate another object, in other words, using an experimental object, like a stick, to push a ball that then makes a noise. The infant actively engages in more experimentation to learn about the physical world. Gravity is learned by pouring water from a cup or pushing bowls off of table tops. The caregiver tries to help the child by picking it up again and placing it back on the table. And what happens? Another experiment! The child pushes it off the table again causing it to fall and the caregiver to pick it up again! [2]

Stage 6, which occurs approximately between 18 and 24 months, is characterized by insight, wherein the child observes how other people manipulate the environment to reach the desired goal, then the child applies that knowledge to obtain the desired goal. The child is now able to solve problems using mental strategies, to remember something heard days before and repeat it, to engage in pretend play, and to find objects that have been moved even when out of sight. Take for instance, a toddler who is upstairs in a room with the door closed, supposedly taking a nap. The doorknob has a safety device on it that makes it impossible for the child to turn the knob. After trying several times to push the door or turn the doorknob, the child carries out a mental strategy learned from prior experience to get the door opened-knocking on the door! The child is now better equipped with mental strategies for problem-solving. [2]

The culmination of stage 6 and the sensorimotor period is the child’s understanding of object permanence, that objects have an existence independent of the child’s interaction with them. Classic examples of understanding object permanence include a child’s realization that when a caregiver leaves a room, the parent continues to exist, or the child’s attempt to recover a hidden toy, indicating the child’s understanding that the toy still exists outside of view (Beilin & Fireman,1999). [2]

[1] Image by Mirjoran is licensed under CC by 2.0.

[2] Scott & Cogburn (2021). Piaget. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. CC by 4.0

[3] Image from Siegler (2021). Cognitive development in childhood. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. CC by SA NC 4.0

[4] “Introduction to Psychology” by Walinga & Stangor. CC by NC SA 4.0

[5] Assimiliation and Accomodation in “Introduction to Psychology” by Walinga & Stangor. CC by NC SA 4.0

[6] Piaget’s Stages of Cognitive Development. in “Introduction to Psychology” by Walinga & Stangor. CC by NC SA 4.0

[7] Image adapted from Clackson et al., (2019). Do helpful mothers help? Effects of maternal scaffolding and infant engagement on cognitive performance. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2661. CC by 4.0

[8] “Psyc 200 Lifespan Psychology” by Laura Overstreet. CC by 4.0

[9] Image by Raul Luna is licensed under CC by 2.0.

[10] Image by Jason Sung is licensed under CC by 4.0

[11] Image by Juan Encalada is licensed under CC by 4.0

[12] Image by Jelleke Vanooteghem is licensed under CC by 4.0

[13] Image by Lubomirkin is licensed under CC by 4.0

[14] Image by Jluis arias is licensed under CC by 4.0