9.5: Theory of Core Knowledge

- Page ID

- 139918

Understanding the Theory of Core Knowledge

The theory of core knowledge proposes that infants are born with ‘core knowledge systems’ that support basic intuitions about the world (Spelke & Kinzler, 2007). Whereas Piaget claimed that children construct knowledge by engaging with the world and Vygotsky claimed children develop cognitively by participating with others in culturally-relevant activities, the theory of core knowledge claims that children are born with basic knowledge. Supporters of this theory suggest that the many studies documenting cognitive abilities in just the first few months of infancy, provide evidence for this theory. For example, Renée Baillargeon’s early work discovered that object permanence is developed in infants at a much younger age than Piaget proposed--already by 3 to 4 months of age (Baillargeon, 1987)! The fact that infants have an understanding of object permanence already, in only the first few months of life, suggests that this knowledge might be inborn. [1]

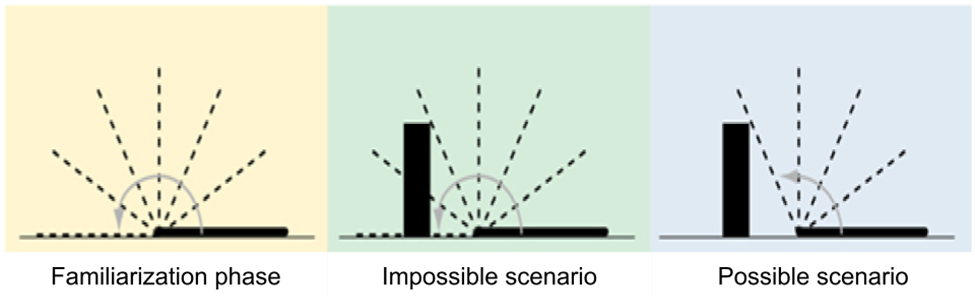

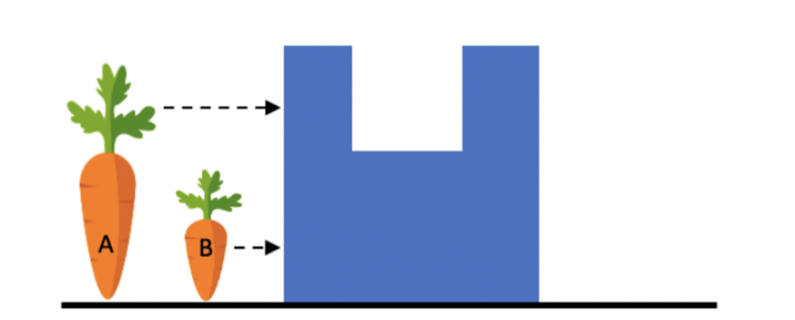

In one experiment on object permanence, young infants were familiarized with a display in which a screen lying flat and facing the infant rotated up and away from the infant 180° in the manner of a drawbridge (Baillargeon, 1987). During the test phase, a new object was then placed at the far edge of the screen, which either did or did not impede the rotating screen (see Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) for a depiction of the experimental scenarios). In the “impossible” scenario, the screen moved exactly as during familiarization, appearing to rotate right through the object. In the “possible” scenario, the screen rotated only to the point where it would be expected to make contact with the object and then stopped moving. Infants looked longer at the “impossible” scenario than the ‘possible’ scenario – which was interpreted in terms of a violation of infants’ expectations regarding object permanence. In another experiment on object permanence (see Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) for a visual depiction of the scenarios), 3 to 4 month old infants looked longer at an impossible event (tall carrot moving behind a box with a section cut out near the top of the box that should have shown the green top of the carrot as it moved behind the box) than the possible event (short carrot moving behind a box with a section cut out near the top of the box that should not have shown the green top of the carrot as it moved behind the box) (Baillargeon & DeVos, 1991).

Building on Baillargeon’s early research, many studies have since continued to document a range of abilities that are collectively described as ‘core systems of knowledge’ and suggest basic inborn knowledge about the physical world (Hamlin, Wynn & Bloom, 2010; Spelke, 1998; Spelke et al., 1992; Spelke & Kinzler, 2007; Wang & Feigenson, 2021). Unlike Piaget’s and Vygotsky’s theories, the theory of core knowledge suggests that some aspects of early knowledge do not need to be learned with experience or from more knowledgeable others because children are instead born with this knowledge. [1]

[1] Grace et al., (2021). Implicit Computation and the Origins of Knowledge. Preprint. CC by 4.0

[2] Image adapted from Turk-Browne et al., (2008). Babies and brains: Habituation in infant cognition and functional neuroimaging. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 2, 16. CC by 4.0

[3] Image from Grace et al., (2021). Implicit Computation and the Origins of Knowledge. Preprint. CC by 4.0

[4] Grace et al., (2021). Implicit Computation and the Origins of Knowledge. Preprint. CC by 4.0