11.11: Development in Language Processing Efficiency

- Page ID

- 140573

Language Processing

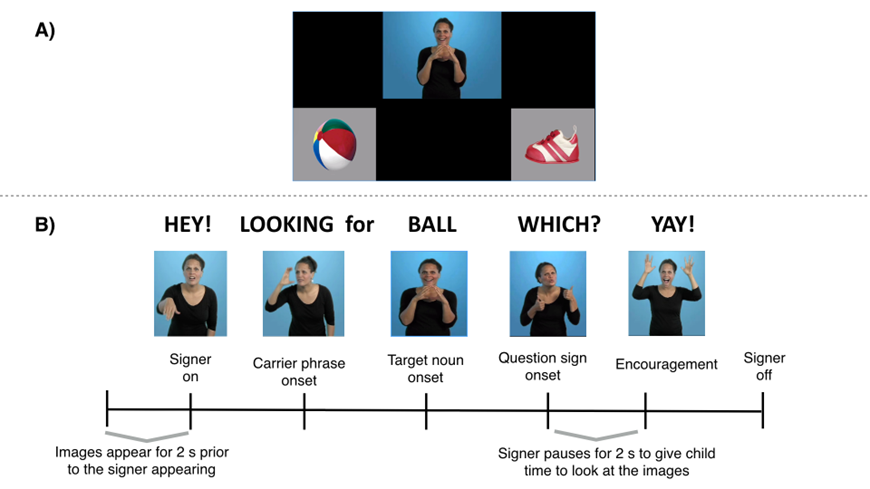

Throughout the second year of life, toddlers are rapidly developing in their ability to understand and produce language. The speed at which children are able to process language while comprehending it, is a critical aspect of language growth during toddlerhood. An experiment called the looking-while-listening (LWL) task has been used to measure language processing efficiency in children. Typically, in LWL tasks, children see a pair of images on a screen (e.g., a ball on the left side of the screen and a shoe on the right) while simultaneously listening to speech that refers to one of these images (e.g., “Where’s the ball?”). Children look towards the objects being named as their eye movements are monitored and are then coded offline to measure the speed with which children move their gaze to the correctly named pictures.[1]

The large body of research using this task has revealed important discoveries:

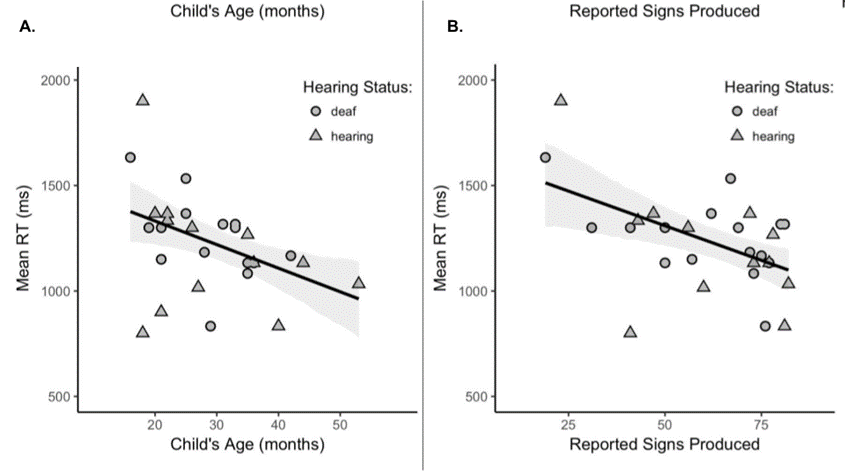

- Maturational improvement. Language development involves more than the ability to understand or express single words—children need to be able to efficiently process streams of language in real-time. Over toddlerhood, children are consistently improving in their ability to rapidly and efficiently process language in real-time (Fernald, Perfors & Marchman, 2006; Fernald et al., 1998; MacDonald et al., 2018).

- Individual differences. While all children improve in their language processing efficiency over time, there are important individual differences early on. Children who have larger expressive vocabularies and who are exposed to more child-directed language are more efficient at processing language in real-time (Hurtado, Marchman & Fernald, 2008; MacDonald et al., 2018; Marchman et al., 2017; Weisleder & Fernald, 2013). Already by eighteen months of age, children from higher SES backgrounds had larger vocabularies and faster response times in the LWL task and by twenty four months of age, there was a six month gap in language processing efficiency ability between children from low and high SES backgrounds (Fernald, Marchman & Weisleder, 2013). Late talking toddlers with more efficient language processing skills at eighteen months of age were more likely to “bloom”, showing greater increases in language ability at thirty months of age (Fernald & Marchman, 2012).

- Links to later abilities. Early language processing abilities are associated not just with language outcomes later in childhood, but also cognitive outcomes as well. Amongst preterm toddlers, those who were more efficient at processing language at eighteen months scored higher on language and IQ tests at fifty-four months of age (Marchman et al., 2018). In a group of children followed longitudinally, language processing at twenty-five months was associated with language and cognitive outcomes at eight years of age (Marchman & Fernald, 2008). One hypothesis for why more efficient language processing leads to these outcomes is that faster processing of familiar words frees up cognitive resources that can then be dedicated to the learning of new words (Fernald & Marchman 2012). [3]

- Caregiver language input increases child language ability. The quantity and quality of language exposure from caregivers is positively associated with toddlers’ language growth. Toddlers who heard more child-directed language from caregivers at 18 to 19 months of age, had larger vocabularies and were more efficient at processing language when they were two years of age (Hurtado, Marchman & Fernald, 2008; Weisleder & Fernald, 2013). It is important to emphasize that it was child-directed language that was most significant, not language that was simply overheard. This research suggests that caregivers should engage in meaningful back-and-forth conversations with infants and toddlers as they increase the quantity and quality of language children are exposed to, especially child-directed language.

[1] Peter, et al., (2019). Does speed of processing or vocabulary size predict later language growth in toddlers? Cognitive Psychology, 115, 101238. CC by 4.0

[2] Image by MacDonald et al., (2017). Real-time lexical comprehension in young children learning American Sign Language. PsyArXiv. CC by 4.0

[3] Peter, et al., (2019). Does speed of processing or vocabulary size predict later language growth in toddlers? Cognitive Psychology, 115, 101238. CC by 4.0