14.8: Strategies for Caregivers Working with Multilingual Infants and Toddlers

- Page ID

- 140765

Caregivers play a key role in supporting the language development of multilingual infants and toddlers (Adamson et al., 2021; Grüter, Hurtado, Marchman & Fernald, 2014). Let’s now take a look at various language strategies caregivers can implement with young multilinguals.

Supporting Heritage Languages

All young children in multilingual environments have the potential to learn multiple languages at the same time and develop a similar level of proficiency in each language (Albareda-Castellot, Pons, & Sebastián-Gallés, 2011; Pearson, Fernandez, Lewedeg, & Oller, 1997). Proficiency requires sufficient exposure and high quality learning opportunities in each language, however, in the U.S. this is rarely the case (Hoff et al., 2012), despite many parents expressing a preference for child care providers who speak the child’s heritage language (Ward, Oldham LaChance, & Atkins, 2011). The term heritage language refers to a language that is spoken at home, but not by the majority of society which uses the societal language. In the U.S. multilingual infants and toddlers are more likely to be in multilingual care when they are 9 months old, less likely at 24 months and very unlikely to receive multilingual childcare services once they are 52 months of age and attending center-based childcare (Espinosa et al., 2017). Multilingual children are exposed to their heritage language in child care less and less as they get older, reflecting the change from care primarily provided by relatives during infancy and early toddlerhood to more center-based care during later toddlerhood and during the preschool years. Relatives were most likely, and caregivers in centers least likely, to use the family’s heritage language. This research suggests that in the U.S. multilingual infants and toddlers who attend childcare programs have fewer opportunities to develop proficiency in both of their languages as English-only learning is most commonly offered in center-based programs. [1] [2] [3]

Center-based caregivers can do a lot to support the multilingual development of infants and toddlers. Caregivers can adapt pedagogical practices to include use of children’s heritage languages in simple ways, such as with posters hung on the wall, books and songs一all including heritage languages. Encourage active engagement with family and community members, who share the same heritage languages as children, as an integral part of the classroom. If possible, hiring staff that use the same languages with enrolled children can be emphasized in job searches. Caregivers can also take the time to learn common words and basic phrases in a child’s heritage language. [1]

Language Quantity and Quality

Just like with monolingual children, the quantity and quality of language multilingual children are exposed to is important (Adamson et al., 2021; Grüter, Hurtado, Marchman & Fernald, 2014). Quantity refers to the amount of language and quality refers to how language is shared with children. Critically, the quantity and quality of the language environment provided by caregivers matters more than the language caregivers use (Song, Luo & Liang, 2021; Unsworth, 2016). Thus, caregivers should primarily communicate with infants and toddlers in the language(s) they are most proficient in so as to maximize the quality of their language input. [5]

Caregivers who expose children to more language, have children with greater language abilities (Hoff, 2006; Weisleder & Fernald, 2013). In one longitudinal study, Spanish/English multilingual toddlers were assessed at 30 months and then again at 36 months of age (Hurtado, Grüter, Marchman & Fernald, 2014). The results revealed that toddlers who were exposed to more language showed greater language abilities. Importantly, the amount of exposure in a particular language was related to the level of growth in that language. So for Spanish/English multilingual toddlers, children who received a higher level of Spanish exposure relative to English, showed greater development in Spanish compared to English. Some research has also found a cross-language relationship with multilingual children, showing that a strong foundation of a heritage language can support the acquisition of an additional language, like English (Cha & Goldenberg, 2015; Kim, Curby & Winsler, 2014; Willard et al., 2021). Spanish/English multilingual toddlers who had stronger Spanish language processing skills at two years of age had stronger English language skills at 4 ½ years of age (Marchman, Bermúdez, Bang & Fernald, 2020). This research is especially important as it provides scientific validation for supporting heritage languages in English-based childcare programs.

Quality of language exposure can include various ways of sharing language with infants and toddlers. When children engage in more frequent and higher-quality language interactions with caregivers they demonstrate better long-term language and academic outcomes (Adamson et al., 2021; Hirsh-Pasek et al., 2015; Huttenlocher et al., 2010; Pace et al., 2019; Storch & Whitehurst, 2002). Although many studies focus on English-speaking families (Hirsh-Pasek et al., 2015; Masek et al., 2021), high-quality, early language interactions also support the communication skills of children from other cultural and linguistic backgrounds. For example, studies investigating Spanish-speaking caregivers’ use of more complex, elaborative language, found that it promoted children’s narrative skills (Escobar, Melzi & Tamis‐LeMonda, 2017; Hammer & Sawyer, 2016; Luo et al., 2014; Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2014). Additionally, more frequent back-and-forth conversations in caregiver–child interactions when the children were 2.5 years of age predicted later language and literacy development in Spanish/English multilingual children (Adamson et al., 2021). [6]

Quality language exposure can occur during any and every interaction caregivers have with infants and toddlers. Let’s now discuss several strategies caregivers can use to improve the quality of language they share with children.

Infant-directed Language

When caregivers interact with infants, their speech often takes on specific, distinguishing features known as infant-directed speech (Fernald et al., 1989). Infant-directed speech (IDS) is produced by caregivers of most (although not all) linguistic and cultural backgrounds and is typically characterized by a slow, melodic, high-pitched, and exaggerated cadence (Broesch & Bryant, 2015; Farran, Lee, Yoo & Oller, 2016; Fernald et al., 1989). From early in life, infants tune their attention to IDS, preferring to listen to IDS over adult-directed speech at birth (Cooper & Aslin, 1990), as well as later in infancy (Cooper & Aslin, 1994; Cooper et al., 1997; Fernald, 1985; Hayashi, Tamekawa & Kiritani, 2001; Kitamura & Lam, 2009; Newman & Hussain, 2006; Santesso et al., 2007; Werker & McLeod, 1989). [7]

Just like monolingual infants, multilingual infants prefer to listen to IDS compared to adult-directed speech (Byers-Heinlein et al., 2021). IDS is an important aspect of quality language exposure to infants not only because they prefer to listen to it, but also because it is related to greater language growth (García-Sierra, Ramírez-Esparza, Wig & Robertson, 2021). Caregivers who use more IDS have infants and toddlers with greater language abilities (Kalashnikova & Carreiras, 2021; Weisleder & Fernald, 2013). Multiple studies have found that greater exposure to IDS is related to a larger vocabulary size in multilingual infants (Ramírez-Esparza et al., 2017; Rosslund, Mayor, Óturai & Kartushina, 2021;). [7]

Reading

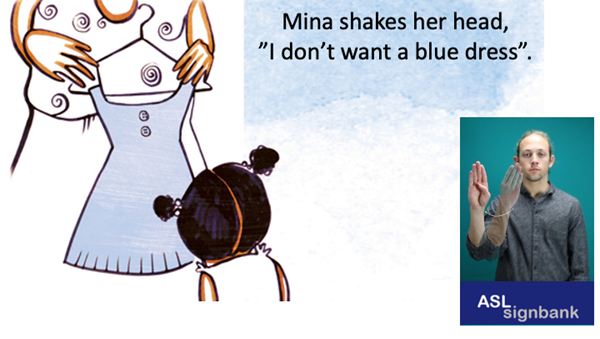

Reading with infants and toddlers is a powerful way to increase both the quantity and quality of language they are exposed to. Just reading one picture book every day can lead to an increase of approximately 78,000 words each year (Logan, Justice, Yumus & Chaparro-Moreno, 2019). Practices such as shared book reading, where a caregiver reads to a child, can support language acquisition (Dolean, 2021; Escobar, Melzi & Tamis‐LeMonda, 2017; Tsybina & Eriks-Brophy, 2010) and literacy abilities (Rodriguez & Tamis‐LeMonda, 2011; Sénéchal & LeFevre, 2002). However, some research suggests that caregivers may tend to emphasize one language over the other in their literacy practices, leading to unbalanced exposure to children’s languages (Gonzalez-Barrero et al., 2021). Furthermore, caregivers often lack access to literacy materials in heritage languages and multilingual formats (Ahooja et al, 2021; Mosty, Lefever & Ragnarsdóttir, 2013; Zhang & Slaughter-Defoe, 2009). For example, Vietnamese families in Taiwan have very few children’s books in Vietnamese at home (Yeh et al., 2015) and Chinese families living in San Francisco have very few resources in Chinese for young children at home (Lao, 2004). [9] [10]

To support the multilingual language development of infants and toddlers through reading, child care programs should have various age-appropriate multilingual books that represent the languages of the children enrolled. Multilingual caregivers who share a heritage language with children, should read in their shared language. Child care programs can invite multilingual family members and community members to come into the program to read with children in their heritage languages. To improve access to age-appropriate books, child care programs can consult enrolled families for quality books and even create multilingual books themselves!

Reading with all children, but especially with infants and toddlers, should be about more than just simply reading the words on the pages. To improve the quality of shared reading, caregivers can implement dialogic reading strategies. Dialogic reading strategies help caregivers create an interaction with a child during shared reading. Dialogic reading typically involves recasts, expansions, and open-ended questions in an attempt to scaffold the interactive reading experience, all of which have been shown to have a positive impact on a child's language development (Baker & Nelson, 1984; Cleave et al., 2015; Girolametto & Weitzman, 2002; Huttenlocher et al., 2010; Opel, Ameer & Aboud, 2009). These strategies are known as the PEER sequence. By implementing the PEER sequence, the caregiver: [12]

- prompts the child to say something about the book,

- evaluates the child's response,

- expands the child's response, and

- repeats the prompt to help the child learn from the expansion.

A fundamental element of dialogic reading is the use of prompts to begin the PEER sequence while reading with a child. The acronym CROWD stands for five recommended prompts: [12]

- Completions

- Recalls

- Open questions

- Wh-questions

- Distancing questions

[1] Espinosa (2015). Challenges and benefits of early bilingualism in the US context. Global Education Review, 2(1). CC by 3.0 NC

[2] Espinosa et al., (2017). Child care experiences among dual language learners in the United States: Analyses of the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study–Birth Cohort. AERA Open, 3(2), 2332858417699380. CC by 4.0

[3] Meir & Janssen (2021). Child Heritage Language Development: An interplay between cross-linguistic influence and language-external factors. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 651730-651730. CC by 4.0

[4] Image from Ramírez & Kuhl (2020). Early second language learning through SparkLing™: Scaling up a language intervention in infant education centers. Mind, Brain, and Education, 14(2), 94-103. CC by 4.0

[5] Luo et al., (2021). Parental beliefs and knowledge, Children’s home language experiences, and school readiness: The dual language perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. CC by 4.0

[6] Rumper et al., (2021). Beyond translation: Caregiver collaboration in adapting an early language intervention. Frontiers in Education, 6.

[7] Byers-Heinlein et al., (2021). A multilab study of bilingual infants: Exploring the preference for infant-directed speech. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 4(1), 2515245920974622. CC by 4.0

[8] Image by M.T ElGassier on Unsplash

[9] Fibla et al., (2021 preprint). Bilingual language development in infancy: What can we do to support bilingual families? CC by 4.0

[10] Ahooja et al., (2021, preprint). Family language policy among Québec-based parents raising multilingual infants and toddlers: A study of resources as a form of language management. CC by 4.0

[11] Image from Sven Brandsma on Unsplash

[12] Noble et al., (2020). The impact of interactive shared book reading on children's language skills: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 63(6), 1878-1897. CC by 4.0