15.16: Facial Expression and Recognition of Emotions

- Page ID

- 140956

Recognizing Emotions

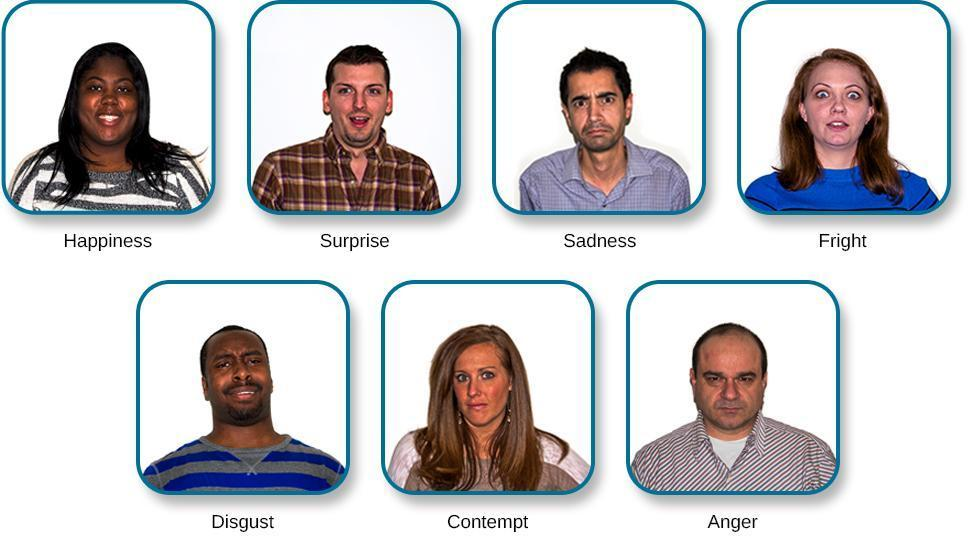

Despite different cultural emotional display rules, our ability to recognize and produce facial expressions of emotion appears to be universal. Even congenitally blind individuals make the same facial expressions of emotions, despite never having had the opportunity to observe these facial displays of emotion in other people. Research findings suggest patterns of activity in the facial muscles involved in generating emotional expressions: this was indicted in the late 19th century in Charles Darwin's (1872) book The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals. Substantial evidence exists for 7 universal emotions associated with distinct facial expressions. These include happiness, surprise, sadness, fright, disgust, contempt, and anger (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) (Ekman & Keltner, 1997, Elkman et al., 1969, Ekman and Friesen, 1971). [1]

(modification of work by Cory Zanker)

In terms of development, it appears that most of the facial components of human expression can be observed shortly after birth. Expressions like enjoyment and interest are present from the first days of life (Sullivan & Lewis, 2003). Researchers initially thought that infants’ facial expressions corresponded to adults’ facial expressions (see Differential emotion theory in Izard & Malatesta, 1987), but it’s now known that facial expressions in infancy are not present like their adult-counterparts (Oster, 2005). Emotion in infancy cannot be compared to emotion in adulthood. Sroufe (1996) described precursor emotions in infancy. Precursor emotions do not have the same degree of cognitive evaluation as emotions of adults. Sroufe described how wariness and frustration can manifest as crying and distress. This observation agrees with the study of Camras et al. (2007) that does not find different facial expressions for fear and anger at 11 months.

Differences between adult and infant facial expressions can also be linked to the motor structure of infant faces. Camras et al. (1996) noted that infants may produce facial expressions in an unrelated situation because of an enlarged recruitment among facial muscles during movement. For example, infants 5 to 7 months raise their brows as they open their mouth, producing an expression of surprise.

Holodynski and Friedlmeier (2006) proposed that infants learned adult-like expressions from a sociocultural based internalization model: caregivers reproduced infant expressions in a selective and exaggerated form, allowing children to learn the connection between their emotion and a given facial expression.[1]

The appearance of adult-like expressions is not well understood (Oster, 2005). Bennett et al. (2005) showed that the organization of facial expressivity increases during infancy. 12-month-old infants showed more specific expression to a situation than 4-month-old infants. It seems that children keep learning how to produce facial expressions through late childhood. Ekman et al. (1980) demonstrated that the ability to produce facial expression improves between 5 and 13 years. However, young children do not perfectly produce all facial expressions. The production of facial expression depends on age and the targeted emotion. Joy is well-produced at 3 years old while anger, sadness, and surprise are still not mastered at 6 years old. Field and Walden (1982) also found that positive emotions are easier to produce than negative emotions. However, Lobue and Thrasher (2014) asked children to imitate facial expressions of an adult and found no effects of age or emotion subtype on the production of facial expression for children between 2 and 8 years old.[2]

Facial expressions of emotion are important regulators of social interaction. This concept has been investigated through social referencing (Klinnert, Campos & Sorce, 1983), the process whereby infants seek out information from others to clarify a situation and then use that information to act. The strongest demonstration of social referencing to date comes from work on the “visual cliff”. In the first study to investigate this concept, Campos and colleagues (Sorce, Emde, Campos, & Klinnert, 1985) placed mothers on the far end of a "cliff" from the infant. First, mothers smiled at their infants and placed a toy on top of the safety glass to attract them: infants invariably began crawling to their mothers. When the infants were in the center of the table, however, the mother then posed an expression of fear, sadness, anger, interest, or joy. The results varied according to the emotion expressed: no infant crossed the table when the mother showed fear, 6% crossed when the mother showed anger, 33% crossed when the mother showed sadness, and approximately 75% of the infants crossed when the mother showed joy or interest.

Other studies provide similar support for facial expressions as regulators of social interaction. In one study (Bradshaw, 1986), experimenters posed facial expressions of neutrality, anger, or disgust toward babies as they moved toward an object and measured the amount of inhibition the babies showed in touching the object. The results for 10- and 15-month-olds were the same: anger produced the greatest inhibition, followed by disgust, then neutrality. This study was later replicated (Hertenstein & Campos, 2004) using joy and disgust expressions, altering the method so that the infants were not allowed to touch the toy (compared with a distractor object) until 1 hour after exposure to the expression. At 14 months of age, significantly more infants touched the toy when they saw joyful expressions, but fewer touched the toy when the infants saw disgust.[3]

[1] Thompson, R. (2021). Social and personality development in childhood is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA

[2] Grossard et. al. (2018) Children Facial Expression Production: Influence of Age, Gender, Emotion Subtype, Elicitation Condition and Culture. is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY).

[3] Hwang, H. & Matsumoto, D. (2021). Functions of emotions is licensed CC BY-SA

[4] Image by Molly Ram is licensed CC BY-NC