16.6: Relationships

- Page ID

- 140966

Relationships and Social Development

Children's experiences of relationships contribute to their expanding repertoire of social skills and broadened social understanding. In these relationships, children develop expectations for specific people (for example, experiences that lead to secure or insecure attachments to parents), acquire knowledge of how to interact with adults and peers, and create a self-concept based on how others respond to them.[1] Relationships with parents, other family members, and caregivers provide critical context for infants' social development. Parents and caregivers are an infant's initial social partner, and the quality of this early caregiver-infant relationship has been linked to many different positive outcomes. Establishing close relationships with adults is related to children's emotional security, sense of self, and evolving understanding of the world around them. Interactions with adults are a frequent and regular part of infants' daily lives, and infants as young as 3 months of age have demonstrated the ability to discriminate between the faces of unfamiliar adults (Barrera & Maurer, 1981). By 4 months of age, a child’s power in relationships, along with the impact of these relationships, is evident. Infants become more skilled at reading others' behavior and adapting their own behavior. They also gain skills to make themselves more engaging and effective socially. 4-month-olds will send clear messages, become quiet in anticipation as someone comes near to care for them, seek adults' attention with smiles and laughter, participate in extended back and forth interaction with others, and engage in simple social imitation.[2]

Close relationships with adults who provide consistent nurturance strengthen a child’s capacity to learn and develop. These special relationships influence the infant's emerging sense of self and understanding of others. Infants use relationships with adults in many ways: for reassurance that they are safe, for assistance in alleviating distress, for help with emotion regulation, and for social approval or encouragement. These relationships play a crucial part in development across all domains. For example, parental responses to the infant's vocalizations support language development (see Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2014 for reviews) and direct gaze sharing between a parent and infant promotes connections and communication (Leong et al., 2017).[3]

Social Understanding

Remarkably, young children begin developing social understanding very early in life. Before the end of the first year, infants are aware that other people have perceptions, feelings, and other mental states that affect their behavior and that differ from their own mental states.[1]

Children begin to understand other people's responses, communication, emotional expression, and actions during the infant and toddler years. These developments include an infant's understanding of what to expect from others, how to act, and which social scripts are used for specific social situations. Recent research suggests that infants' and toddlers' social understanding is related to how often they experience adult communication about the thoughts and emotions of others (Taumoepeau & Ruffman, 2008).[2]

"At each age, social cognitive understanding contributes to social competence, interpersonal sensitivity, and an awareness of how the self relates to other individuals and groups in a complex social world" (Thompson, 2006, pg.26). Even in early infancy, social understanding is critical because of the social nature of humans (Wellman & Lagattuta, 2000).[2]

Responding to Infants' Cues as Part of Social Development Through Joint Attention and Social Referencing

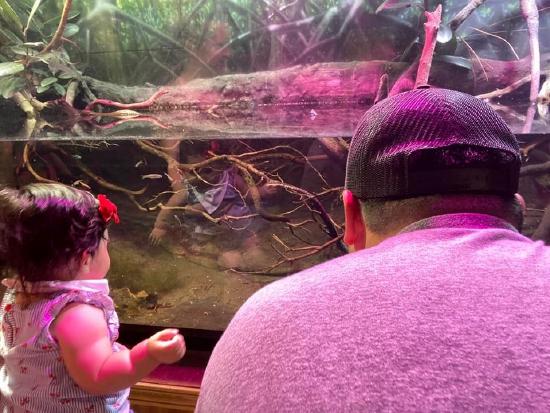

Humans can actively engage with other people's mental states, such as when they enter situations of joint attention (Malle, 2022). Joint attention is described as the ability to coordinate visual attention with another person and then shift the gaze toward an object or event (Mundy, 1998); it does not require the gazer to be aware of the follower's reaction (Emery, 2000). The definition sounds more complicated than it is. If you point to an object around a 3-year-old, notice how you both check in, ensuring that you are jointly engaging with the object. Such shared engagement is critical for children to learn the meaning of objects: both their value (is it safe and rewarding to approach?) and the words that refer to them (what do you call this?). When I hold up my keyboard and show it to you, we are jointly attending to it, and if I say it's called "Tastatur" in German, you know that I am referring to the keyboard and not to the table on which it had been resting.[4]

Literature reports 2 main components of joint attention: (1) response to joint attention and (2) initiation of joint attention.

Responding to joint attention is the ability to shift visual attention following another's social cues such as gaze or pointing, whereas initiating joint attention is the ability to direct another person's attention through gaze or gestures with the aim of sharing an experience (Seibert & Mundy, 1982). Responding to joint attention and initiating joint attention are considered interrelated aspects of joint attention, emerging at different times during development (Mundy et al., 2007). Responding to joint attention usually develops between 6 and 9 months of age, whereas initiating joint attention starts approximately at 9 months of age with significant variability across individuals.[5]

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Example of joint attention as both man and infant look at the same object. ([11])

Social Referencing

Young children begin developing social understanding very early in life. Before the end of the first year, an infant is aware that other people have perceptions, feelings, and different mental states affecting their behavior.[1] An understanding that other mental states differ from the infant’s own can be readily observed in the phenomena of social referencing. [1] Social referencing is the tendency of an infant to gather information from a caregiver to regulate his behavior in an ambiguous situation (in which the infant does not have enough information to decide how to react) (Fawcett & Liszkowski, 2015; Schieler et al., 2018; Stenberg, 2009; Striano et al., 2006; Walden and Kim, 2005; Zarbatany and Lamb, 1985). Social referencing emerges around 7 to 10 months of age and forms a foundation for social learning and social appraisal in adulthood (Walle et al., 2017).[1]

In social referencing, an infant looks to a trusted caregiver's face when confronted with an unfamiliar person or situation (Feinman, 1992). If the caregiver seems calm and reassuring, the infant responds positively as if the situation is safe. If the caregiver looks fearful or distressed, the infant is likely to react with wariness or distress because the caregiver's expression signals danger. Infants display remarkable insight and awareness: even though they are uncertain about the unfamiliar situation, the caregiver is not. By "reading" the emotion in the caregiver’s face, infants can learn about whether the circumstance is safe or dangerous, and how to respond. [1]

In the past, developmental scientists believed infants were egocentric—focused on their perceptions and experience—but research now indicates the opposite is true. From an early age, infants are aware that people have different mental states, which motivates them to figure out what others are feeling, intending, wanting, and thinking, and how these mental states affect their behavior. Infants are beginning to develop a theory of mind, and although their understanding of mental states begins very simply, it expands rapidly (Wellman, 2011)Social understanding grows significantly as children's theory of mind develops.[1]

How do these achievements in social understanding occur? Young children are remarkably sensitive observers of other people. They make connections between their emotional expressions, words, and behavior to derive simple inferences about mental states (e.g., concluding that what Mommy is looking at is in her mind) (Gopnik, Meltzoff, & Kuhl, 2001). This connection is especially likely to occur in relationships with people the child knows well, consistent with the ideas of attachment theory. Growing language skills give young children words with which to represent these mental states (e.g., "mad," "wants") and talk about them with others. Through conversation with their caregivers about everyday experiences, children learn much about people's mental states from how adults talk about them ("Your sister was sad because she thought Daddy was coming home.”) (Thompson, 2006). Developing social understanding depends heavily upon children's everyday interactions with others and their careful interpretations of what they see and hear.[1]

Disturbances in Infant-Caregiver Relationships: Maternal Depression and Infant and Toddler Social Development

Infants repeatedly participate in daily, interactive routines with their primary caregivers, most often their mothers. An infant is typically in tune with the emotional signals in their caregivers' voices, gestures, movements, and facial expressions. Maternal depression compromises the infant and mother’s ability to mutually regulate the interaction. Most commonly, depression impacts the relationship through 2 interactive patterns observed in depressed mothers: intrusiveness or withdrawal. Intrusive mothers display a negative affect and disrupt the infant's activity. The infant experiences anger, turns away from the mother to limit her intrusiveness, and internalizes an angry and protective coping style. Withdrawn mothers are disengaged, unresponsive, affectively flat and do little to support the infant's activity. Infants cannot cope with or self-regulate this negative state and develop passivity, withdrawal, and self-regulatory behaviors (e.g., looking away or sucking on the thumb) (Hart et al., 1998; Tronick, 1989).

Infants and toddlers of depressed mothers can develop serious emotional disorders such as infant depression and attachment disorders (Luby, 2000). Early mental health disorders might be reflected by delayed development, inconsolable crying, or sleep problems. Older toddlers may exhibit aggressive or impulsive behavior. In early care and education settings, children with social and emotional problems tend to have a hard time relating to others, trusting adults, being motivated to learn, and calming themselves to tune into teaching—all necessary skills to benefit from early educational experiences. Studies reveal the long-lasting effects of maternal depression. Older children of mothers depressed during infancy show poor self-control, aggression, poor peer relationships, and difficulty in school (Embry & Dawson, 2002). These problems increase the likelihood that the child will be placed in special education, held back to repeat a grade, or drop out of school. Each of these problems can prevent a child from reaching optimal development, result in missed opportunities for success over the child's lifespan, and impose increased costs to society (Onunaku, 2005).

When Relationships Cause Damage: Abuse and Neglect

It is challenging to know how much child abuse occurs. Infants cannot talk, and toddlers and older children who are abused usually do not tell anyone about the abuse. They might not define it as abuse, they might be scared to tell a trusted adult, they might blame themselves for being abused, or they might not know with whom they could talk about their abuse. Whatever the reason, children usually remain silent, making it very difficult to know how much abuse occurs. Up-to-date statistics on the different types of child abuse in the United States can be found at the U.S. Children's Bureau website .[7]

All types of abuse are complex issues, especially within families. There are many reasons people may become abusers- poverty, stress, and substance abuse are common characteristics shared by abusers, although abuse can happen in any family.

Children who experience abuse or neglect are at risk of developing lifelong social, emotional, and health problems, particularly if neglected before the age of 2. However, it is essential to note that not all children who experience abuse and neglect will have the same outcomes. There are many ways to foster stable, permanent, safe, secure, nurturing, loving care for children affected by adverse childhood experiences.

Trauma-Informed Care

Traumatic experiences can significantly alter a person's perception of themselves, their environment, and the people around them. As traumatic experiences accumulate, responses become more intense and have a greater impact on functioning. Ongoing exposure to traumatic stress can impact all areas of people's lives, including biological, cognitive, and emotional functioning, as well as social interactions, relationships and identity formation. Because people who have experienced multiple traumas do not relate to the world in the same way as those who have not had these experiences, they require services and responses that are sensitive to their unique experiences and needs.[9]

Toxic stresses, such as abuse and neglect, are strongly linked to poor health outcomes across one’s lifespan and trauma-informed care is one approach to caregiving based on these effects. Caregivers in trauma-informed care strive to understand children’s behavior in the context of previous traumas they have experienced. Trauma-informed care for infants and toddlers begins with first recognizing the prevalence and potential impact these stresses can have during the first 3 years. Caregivers also provide supportive care, enhancing children’s feelings of safety and security, to prevent their re-traumatization in a current situation that may potentially overwhelm their coping skills.[10]

[1] Thompson, R. (2022). Social and personality development in childhood Is licensed CC BY-NC-SA

[2] California Infant/Toddler Learning and Development Foundations, 2009 by the California Department of Education is used with permission

[3] Zosh J.M. et. al., (2018) Accessing the Inaccessible: Redefining Play as a Spectrum Licensed (CC BY)

[4] Malle, B. (2022). Theory of mind. licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA

[5] Billeci, L., Narzisi, A., Campatelli, G. et al. Disentangling the initiation from the response in joint attention: an eye-tracking study in toddlers with autism spectrum disorders. Is licensed CC BY

[6] Ehli S, Wolf J, Newen A, Schneider S and Voigt B (2020) Determining the Function of Social Referencing: The Role of Familiarity and Situational Threat. (CC BY).

[7] Child Abuse, Neglect, and Foster Care is shared under a not declared license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by Diana Lang

[8] Child, Family, and Community (Laff and Ruiz) is shared under a CC BY license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by Rebecca Laff and Wendy Ruiz

[9] Ayre, K., & Krishnamoorthy, G. (2020). Understand and empathise is licensed under CC BY-SA.

[10] Sanders & Hall (2018). Trauma-informed care in the newborn intensive care unit: Promoting safety, security and connectedness.CC by NC SA 4.0

[11] Image by Joy Poeng is licensed CC BY-NC

[12] Image by Rachel Klippenstein-Gutierrez is licensed CC BY-NC