Canadians held M2 money balances of $1,510 billion in January 2017. Three variables that may explain the size of these holdings are: the interest rate, the price level, and real income. Together they provide the basis for a theory of the demand for money.

Why hold money?

It is important to distinguish between money and income when discussing the demand for money. You might have a high income but no money, or no income and lots of money. That is because income is a flow of funds over a period of time. If you spend your income as it is received you will not accumulate a stock of money. Alternatively, you might have a stock of money or a money balance but no income. Then you can choose to either hold or spend your money. If you have no income you can finance a flow of expenditures by spending your money balance.

In Chapter 8, money was a means of payment and a store of value. Those two functions motivate the demand to hold at least some wealth in money balances. There are alternative stores of value. Bonds, equities, precious metals, real estate, and art are a few examples. The quantity of money people choose to hold is part of the portfolio decision they make about their wealth. They choose money instead of some other asset.

To develop the demand for money balances it is useful to simplify the portfolio decisions by assuming there are only two assets:

- Money, which has a constant money price, pays no interest income but does serve as the means of payment.

- Bonds, representing all interest-earnings assets, have money prices that change if market interest rates change, but are not means of payment.

The financial wealth people build up by saving some of their income calls for a decision. People could hold this wealth as money, which pays no interest, but is a safe asset because its price is constant. Or they could hold this wealth in bonds, which pay interest income but are risky because bond prices move up and down as market interest rates move down and up. If the expected return to holding bonds is positive (due to the interest rate together with any change in price) why would people hold any money balances?

The demand for money comes in three parts, namely:

- The transactions demand;

- The precautionary demand; and

- The asset or speculative demand.

The transactions demand

As the name suggests, the transactions demand for money is based on money being the means of payment. People and businesses hold some money to pay for their purchases of goods, services and assets. This demand reflects the lack of coordination of receipts and payments. Income is paid bi-weekly or monthly but purchases are made more frequently and in smaller amounts. Pocket money and bank balances that can be transferred by debit card are readily available to make these purchases between paydays. If all income receipts were used on paydays to buy bonds to earn interest income it would be costly and inconvenient to sell bond holdings bit by bit as payments were made. The costs of frequent switching between money, bonds and money would more than offset any interest income earned from very-short-term bond holdings.

The precautionary demand

Uncertainty about the timing of receipts and payments creates a precautionary demand for money balances. There are two sides to this uncertainty. On one side there may be some unexpected changes in the timing or size of income receipts. Regular payments can still be made if enough money is available, over and above that need for usual expenses and payments. Alternatively, unexpected or emergency expenses in terms of appliance, computer or car breakdowns or unexpected opportunities for bargains or travel can by covered by precautionary money holdings. Money balances cover the unexpected gaps between income receipts and payment requirements without the costs and inconvenience of selling bonds on short notice.

The asset or speculative demand

The asset or speculative demand comes from financial portfolio decisions rather than the lack of coordination and uncertainty behind the two preceding demands. Businesses and professional portfolio managers use money balances to take advantage of expected changes in interest rates. Essentially they speculate by switching between bonds and money based on their own forecasts of future interest rates.

Recall that bond prices and interest rates vary inversely. If while holding money balances you predict a fall in interest rates, you buy bonds. If your prediction is right and interest rates do fall, the prices of your bonds rise. Now you can sell and harvest the capital gain you earned by speculating in the bond market. Alternatively, if you correctly predict a rise in interest rates and act before it happens you can avoid a capital loss on your bond holds by selling and holding money before the interest rate rises.

Even if portfolio managers are not interested in speculating on interest rate changes there is an asset demand for money. A mixed portfolio of money and bonds is less risky than one that holds only bonds. The money component has a stable market price while the bond component provides interest income along with the risk of a variable price. Changing the shares of money and bonds in the portfolio allows the manager a trade-off between return and risk. However, as interest rates rise the opportunity cost of holding a share of the portfolio in money rises. Furthermore, the estimated risk from the bond share of the portfolio may fall if interest rates are expected to fall in the near future. As a result, rising interest rates reduce the asset demand for money balances.

The demand for money function

The demand for money balances is summarized by a simple equation. Let the size of the real money balances people wish to hold for transactions and precautionary reasons (Lt) be a fraction k of GDP. With nominal GDP defined as real GDP (Y) times the GDP deflator (P), nominal  . Using this notation, the demand for nominal money balances for transactions and precautionary reasons is kPY, and the demand for real balances is kY, where k is a positive fraction. When real income changes, bringing with it changes in spending, the change in the demand for real money balances changes is determined by k. This makes a link between part of the demand for money balances (Lt) and income, namely Lt=kY.

. Using this notation, the demand for nominal money balances for transactions and precautionary reasons is kPY, and the demand for real balances is kY, where k is a positive fraction. When real income changes, bringing with it changes in spending, the change in the demand for real money balances changes is determined by k. This makes a link between part of the demand for money balances (Lt) and income, namely Lt=kY.

What is the value of k in Canada? In the second quarter of 2015, Canadians held money balances as measured by M2 of $1,325 billion. Nominal GDP in that quarter was $1,364 billion measured at an annual rate. If we divide M2 holdings by GDP, we get k=1,325/1,364=0.97, or about 97 percent of annual income. This value of k suggests that a rise in GDP of $100 will increase the demand for money balances by $97, measured in either nominal or real terms.

Changes in nominal interest rates also change the size of the money balances people wish to hold, based on the asset motive. A rise in interest rates increases the opportunity cost of holding money balances rather than bonds. It may also create the expectation that interest rates in the future will fall back to previous levels. As a result, people will want to use some of their money balances to buy bonds, changing the mix of money and bonds in their wealth holdings. A fall in interest rates has the opposite effect.

The way people adjust their portfolios in response to changes in interest rates results in a negative relationship between the asset demand for money balances and the nominal interest rate. Then using –h to measure the change in money balances in response to a change in interest rates can be written as  . If individual and institutional portfolio mangers' decisions are very sensitive to the current interest rates, h will be a large negative number. A small rise in interest rates will cause a large shift from money to bonds. Alternatively, if portfolio decisions are not at all sensitive to interest rate changes, h would be zero.

. If individual and institutional portfolio mangers' decisions are very sensitive to the current interest rates, h will be a large negative number. A small rise in interest rates will cause a large shift from money to bonds. Alternatively, if portfolio decisions are not at all sensitive to interest rate changes, h would be zero.

Putting these components of the demand for real money balances together gives the demand for money function, which is a demand to hold real money balances L:

|

(9.1) |

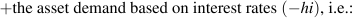

Figure 9.1 shows the relationship between the demand for real money balances and the interest rate, drawn for a given level of real GDP, Y0. The demand for money function would have an intercept of kY0 on the horizontal axis. At higher interest rates the opportunity cost of holding money balances is higher because the expected return from holding bonds is positive. The negative slope of the demand function shows how people change their demand for money when interest rates change. The slope of the demand curve for money is –1/h. The effect of a change in the interest rate is shown by a movement along the L function. A change in real income would require us to draw a new demand for money function, to the right of L0 if Y increased, or to the left if Y decreased.

This straight line demand for money function is a useful simplification. However, it would be more realistic to draw the function with a decreasing slope as interest rates decline. That would capture two important ideas.

First, as interest rates fall, and fall relative to the costs of buying and selling bonds, opportunity costs decline faster than interest rates.

Second, consider the speculative demand for money. As interest rates fall, the riskiness of bonds increases. A subsequent rise in interest rates has a larger negative effect on bond prices. Expectations of future increases in interest rates may strengthen as interest rates decline. As a result, portfolio managers may shift funds increasingly from bonds to money as interests fall. If their expectations are confirmed by events they avoid the capital losses caused by falling bond prices.

. Using this notation, the demand for nominal money balances for transactions and precautionary reasons is kPY, and the demand for real balances is kY, where k is a positive fraction. When real income changes, bringing with it changes in spending, the change in the demand for real money balances changes is determined by k. This makes a link between part of the demand for money balances (Lt) and income, namely Lt=kY.

. Using this notation, the demand for nominal money balances for transactions and precautionary reasons is kPY, and the demand for real balances is kY, where k is a positive fraction. When real income changes, bringing with it changes in spending, the change in the demand for real money balances changes is determined by k. This makes a link between part of the demand for money balances (Lt) and income, namely Lt=kY. . If individual and institutional portfolio mangers' decisions are very sensitive to the current interest rates, h will be a large negative number. A small rise in interest rates will cause a large shift from money to bonds. Alternatively, if portfolio decisions are not at all sensitive to interest rate changes, h would be zero.

. If individual and institutional portfolio mangers' decisions are very sensitive to the current interest rates, h will be a large negative number. A small rise in interest rates will cause a large shift from money to bonds. Alternatively, if portfolio decisions are not at all sensitive to interest rate changes, h would be zero.