3: The classical marketplace – demand and supply

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 108282

Chapter 3: The classical marketplace – demand and supply

In this chapter we will explore:

| 3.1 | The marketplace – trading |

| 3.2 | The market's building blocks |

| 3.3 | Demand curves and supply curves |

| 3.4 | Non-price determinants of demand |

| 3.5 | Non-price determinants of supply |

| 3.6 | Simultaneous demand and supply movements |

| 3.7 | Free and managed markets – interventions |

| 3.8 | From individuals to markets |

| 3.9 | Useful techniques – demand and supply equations |

3.1 The marketplace – trading

The marketplace in today's economy has evolved from earlier times. It no longer has a unique form – one where buyers and sellers physically come together for the purpose of exchange. Indeed, supermarkets usually require individuals to be physically present to make their purchases. But when purchasing an airline ticket, individuals simply go online and interact with perhaps a number of different airlines (suppliers) simultaneously. Or again, individuals may simply give an instruction to their stock broker, who will execute a purchase on their behalf – the broker performs the role of a middleman, who may additionally give advice to the purchaser. Or a marketing agency may decide to subcontract work to a translator or graphic artist who resides in Mumbai. The advent of the coronavirus has shifted grocery purchases from in-store presence to home delivery for many buyers. In pure auctions (where a single work of art or a single residence is offered for sale) buyers compete one against the other for the single item supplied. Accommodations in private homes are supplied to potential visitors (buyers) through Airbnb. Taxi rides are mediated through Lyft or Uber. These institutions are all different types of markets; they serve the purpose of facilitating exchange and trade.

Not all goods and services in the modern economy are obtained through the marketplace. Schooling and health care are allocated in Canada primarily by government decree. In some instances the market plays a supporting role: Universities and colleges may levy fees, and most individuals must pay, at least in part, for their pharmaceuticals. In contrast, broadcasting services may carry a price of zero; Buzzfeed or other news and social media come free of payment. Furthermore, some markets have no price, yet they find a way of facilitating an exchange. For example, graduating medical students need to be matched with hospitals for their residencies. Matching mechanisms are a form of market in that they bring together suppliers and demanders. We explore their operation in Chapter 11.

The importance of the marketplace springs from its role as an allocating mechanism. Elevated prices effectively send a signal to suppliers that the buyers in the market place a high value on the product being traded; conversely when prices are low. Accordingly, suppliers may decide to cease supplying markets where prices do not remunerate them sufficiently, and redirect their energies and the productive resources under their control to other markets – markets where the product being traded is more highly valued, and where the buyer is willing to pay more.

Whatever their form, the marketplace is central to the economy we live in. Not only does it facilitate trade, it also provides a means of earning a livelihood. Suppliers must hire resources – human and non-human – in order to bring their supplies to market and these resources must be paid a return: income is generated.

In this chapter we will examine the process of price formation – how the prices that we observe in the marketplace come to be what they are. We will illustrate that the price for a good is inevitably linked to the quantity of a good; price and quantity are different sides of the same coin and cannot generally be analyzed separately. To understand this process more fully, we need to model a typical market. The essentials are demand and supply.

3.2 The market's building blocks

In economics we use the terminology that describes trade in a particular manner. Non-economists frequently describe microeconomics by saying "it's all about supply and demand". While this is largely true we need to define exactly what we mean by these two central words. Demand is the quantity of a good or service that buyers wish to purchase at each conceivable price, with all other influences on demand remaining unchanged. It reflects a multitude of values, not a single value. It is not a single or unique quantity such as two cell phones, but rather a full description of the quantity of a good or service that buyers would purchase at various prices.

Demand is the quantity of a good or service that buyers wish to purchase at each possible price, with all other influences on demand remaining unchanged.

As a hypothetical example, the first column of Table 3.1 shows the price of natural gas per cubic foot. The second column shows the quantity that would be purchased in a given time period at each price. It is therefore a schedule of quantities demanded at various prices. For example, at a price $6 per unit, buyers would like to purchase 4 units, whereas at the lower price of $3 buyers would like to purchase 7 units. Note also that this is a homogeneous good. A cubit foot of natural gas is considered to be the same product no matter which supplier brings it to the market. In contrast, accommodations supplied through Airbnb are heterogeneous – they vary in size and quality.

| Price ($) | Demand (thousands | Supply (thousands | Excess |

| of cu feet) | of cu feet) | ||

| 10 | 0 | 18 | Excess Supply |

| 9 | 1 | 16 | |

| 8 | 2 | 14 | |

| 7 | 3 | 12 | |

| 6 | 4 | 10 | |

| 5 | 5 | 8 | |

| 4 | 6 | 6 | Equilibrium |

| 3 | 7 | 4 | Excess Demand |

| 2 | 8 | 2 | |

| 1 | 9 | 0 | |

| 0 | 10 | 0 |

Supply is interpreted in a similar manner. It is not a single value; we say that supply is the quantity of a good or service that sellers are willing to sell at each possible price, with all other influences on supply remaining unchanged. Such a supply schedule is defined in the third column of the table. It is assumed that no supplier can make a profit (on account of their costs) unless the price is at least $2 per unit, and therefore a zero quantity is supplied below that price. The higher price is more profitable, and therefore induces a greater quantity supplied, perhaps by attracting more suppliers. This is reflected in the data. For example, at a price of $3 suppliers are willing to supply 4 units, whereas with a price of $7 they are willing to supply 12 units. There is thus a positive relationship between price and quantity for the supplier – a higher price induces a greater quantity; whereas on the demand side of the market a higher price induces a lower quantity demanded – a negative relationship.

Supply is the quantity of a good or service that sellers are willing to sell at each possible price, with all other influences on supply remaining unchanged.

We can now identify a key difference in terminology – between the words demand and quantity demanded, and between supply and quantity supplied. While the words demand and supply refer to the complete schedules of demand and supply, the terms quantity demanded and quantity supplied each define a single value of demand or supply at a particular price.

Quantity demanded defines the amount purchased at a particular price.

Quantity supplied refers to the amount supplied at a particular price.

Thus while the non-economist may say that when some fans did not get tickets to the Stanley Cup it was a case of demand exceeding supply, as economists we say that the quantity demanded exceeded the quantity supplied at the going price of tickets. In this instance, had every ticket been offered at a sufficiently high price, the market could have generated an excess supply rather than an excess demand. A higher ticket price would reduce the quantity demanded; yet would not change demand, because demand refers to the whole schedule of possible quantities demanded at different prices.

Other things equal – ceteris paribus

The demand and supply schedules rest on the assumption that all other influences on supply and demand remain the same as we move up and down the possible price values. The expression other things being equal, or its Latin counterpart ceteris paribus, describes this constancy of other influences. For example, we assume on the demand side that the prices of other goods remain constant, and that tastes and incomes are unchanging. On the supply side we assume, for example, that there is no technological change in production methods. If any of these elements change then the market supply or demand schedules will reflect such changes. For example, if coal or oil prices increase (decline) then some buyers may switch to (away from) gas or solar power. This will be reflected in the data: At any given price more (or less) will be demanded. We will illustrate this in graphic form presently.

Market equilibrium

Let us now bring the demand and supply schedules together in an attempt to analyze what the marketplace will produce – will a single price emerge that will equate supply and demand? We will keep other things constant for the moment, and explore what materializes at different prices. At low prices, the data in Table 3.1 indicate that the quantity demanded exceeds the quantity supplied – for example, verify what happens when the price is $3 per unit. The opposite occurs when the price is high – what would happen if the price were $8? Evidently, there exists an intermediate price, where the quantity demanded equals the quantity supplied. At this point we say that the market is in equilibrium. The equilibrium price equates demand and supply – it clears the market.

The equilibrium price equilibrates the market. It is the price at which quantity demanded equals the quantity supplied.

In Table 3.1 the equilibrium price is $4, and the equilibrium quantity is 6 thousand cubic feet of gas (we use the notation 'k' to denote thousands). At higher prices there is an excess supply—suppliers wish to sell more than buyers wish to buy. Conversely, at lower prices there is an excess demand. Only at the equilibrium price is the quantity supplied equal to the quantity demanded.

Excess supply exists when the quantity supplied exceeds the quantity demanded at the going price.

Excess demand exists when the quantity demanded exceeds the quantity supplied at the going price.

Does the market automatically reach equilibrium? To answer this question, suppose initially that the sellers choose a price of $10. Here suppliers would like to supply 18k cubic feet, but there are no buyers—a situation of extreme excess supply. At the price of $7 the excess supply is reduced to 9k, because both the quantity demanded is now higher at 3k units, and the quantity supplied is lower at 12k. But excess supply means that there are suppliers willing to supply at a lower price, and this willingness exerts continual downward pressure on any price above the price that equates demand and supply.

At prices below the equilibrium there is, conversely, an excess demand. In this situation, suppliers could force the price upward, knowing that buyers will continue to buy at a price at which the suppliers are willing to sell. Such upward pressure would continue until the excess demand is eliminated.

In general then, above the equilibrium price excess supply exerts downward pressure on price, and below the equilibrium excess demand exerts upward pressure on price. This process implies that the buyers and sellers have information on the various elements that make up the marketplace.

We will explore later in this chapter some specific circumstances in which trading could take place at prices above or below the equilibrium price. In such situations the quantity actually traded always corresponds to the short side of the market: this means that at high prices the quantity demanded is less than the quantity supplied, and it is the quantity demanded that is traded because buyers will not buy the amount suppliers would like to supply. Correspondingly, at low prices the quantity demanded exceeds quantity supplied, and it is the amount that suppliers are willing to sell that is traded. In sum, when trading takes place at prices other than the equilibrium price it is always the lesser of the quantity demanded or supplied that is traded. Hence we say that at non-equilibrium prices the short side dominates. We will return to this in a series of examples later in this chapter.

The short side of the market determines outcomes at prices other than the equilibrium.

Supply and the nature of costs

Before progressing to a graphical analysis, we should add a word about costs. The supply schedules are based primarily on the cost of producing the product in question, and we frequently assume that all of the costs associated with supply are incorporated in the supply schedules. In Chapter 6 we will explore cases where costs additional to those incurred by producers may be relevant. For example, coal burning power plants emit pollutants into the atmosphere; but the individual supplier may not take account of these pollutants, which are costs to society at large, in deciding how much to supply at different prices. Stated another way, the private costs of production would not reflect the total, or full social costs of production. Conversely, if some individuals immunize themselves against a rampant virus, other individuals gain from that action because they become less likely to contract the virus - the social value thus exceeds the private value. For the moment the assumption is that no such additional costs are associated with the markets we analyze.

3.3 Demand and supply curves

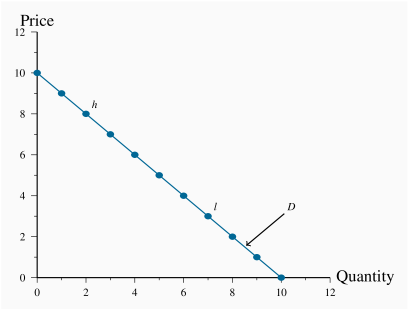

The demand curve is a graphical expression of the relationship between price and quantity demanded, holding other things constant. Figure 3.1 measures price on the vertical axis and quantity on the horizontal axis. The curve D represents the data from the first two columns of Table 3.1. Each combination of price and quantity demanded lies on the curve. In this case the curve is linear—it is a straight line. The demand curve slopes downward (technically we say that its slope is negative), reflecting the fact that buyers wish to purchase more when the price is less.

To derive this demand curve we take each price-quantity combination from the

demand schedule in Table 3.1 and insert a point that corresponds to those

combinations. For example, point h defines the combination ![]() , the point l denotes the combination

, the point l denotes the combination ![]() .

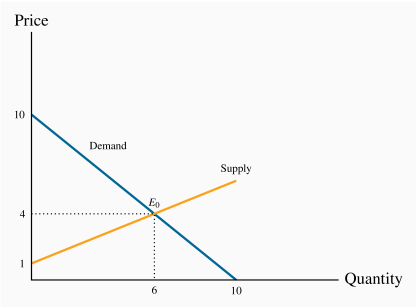

If we join all such points we obtain the demand curve in Figure 3.2.The same process yields the supply curve in Figure 3.2. In this example the supply and the demand curves are each

linear. There is no reason why this linear property characterizes demand and

supply curves in the real world; they are frequently found to have

curvature. But straight lines are easier to work with, so we continue with

them for the moment.

.

If we join all such points we obtain the demand curve in Figure 3.2.The same process yields the supply curve in Figure 3.2. In this example the supply and the demand curves are each

linear. There is no reason why this linear property characterizes demand and

supply curves in the real world; they are frequently found to have

curvature. But straight lines are easier to work with, so we continue with

them for the moment.

The demand curve is a graphical expression of the relationship between price and quantity demanded, with other influences remaining unchanged.

The supply curve is a graphical representation of the relationship between price and quantity supplied, holding other things constant. The supply curve S in Figure 3.2 is based on the data from columns 1 and 3 in Table 3.1. It has a positive slope indicating that suppliers wish to supply more at higher prices.

The supply curve is a graphical expression of the relationship between price and quantity supplied, with other influences remaining unchanged.

The demand and supply curves intersect at point E0, corresponding to a price of $4 which, as illustrated above, is the equilibrium price for this market. At any price below this the horizontal distance between the supply and demand curves represents excess demand, because demand exceeds supply. Conversely, at any price above $4 there is an excess supply that is again measured by the horizontal distance between the two curves. Market forces tend to eliminate excess demand and excess supply as we explained above. In the final section of the chapter we illustrate how the supply and demand curves can be 'solved' for the equilibrium price and quantity.

3.4 Non-price influences on demand

We have emphasized several times the importance of the ceteris paribus assumption when exploring the impact of different prices on the quantity demanded: We assume all other influences on the purchase decision are unchanged (at least momentarily). These other influences fall into several broad categories: The prices of related goods; the incomes of buyers; buyer tastes; and expectations about the future. Before proceeding, note that we are dealing with market demand rather than demand by one individual (the precise relationship between the two is developed later in this chapter).

The prices of related goods – oil and gas, Kindle and paperbacks

We expect that the price of other forms of energy would impact the price of natural gas. For example, if hydro-electricity, oil or solar becomes less expensive we would expect some buyers to switch to these other products. Alternatively, if gas-burning furnaces experience a technological breakthrough that makes them more efficient and cheaper we would expect some users of other fuels to move to gas. Among these examples, oil and electricity are substitute fuels for gas; in contrast a more fuel-efficient new gas furnace complements the use of gas. We use these terms, substitutes and complements, to describe products that influence the demand for the primary good.

Substitute goods: when a price reduction (rise) for a related product reduces (increases) the demand for a primary product, it is a substitute for the primary product.

Complementary goods: when a price reduction (rise) for a related product increases (reduces) the demand for a primary product, it is a complement for the primary product.

Clearly electricity is a substitute for gas in the power market, whereas a gas furnace is a complement for gas as a fuel. The words substitutes and complements immediately suggest the nature of the relationships. Every product has complements and substitutes. As another example: Electronic readers and tablets are substitutes for paper-form books; a rise in the price of paper books should increase the demand for electronic readers at any given price for electronic readers. In graphical terms, the demand curve shifts in response to changes in the prices of other goods – an increase in the price of paper-form books shifts the demand for electronic readers outward, because more electronic readers will be demanded at any price.

Buyer incomes – which goods to buy

The demand for most goods increases in response to income growth. Given this, the demand curve for gas will shift outward if household incomes in the economy increase. Household incomes may increase either because there are more households in the economy or because the incomes of the existing households grow.

Most goods are demanded in greater quantity in response to higher incomes at any given price. But there are exceptions. For example, public transit demand may decline at any price when household incomes rise, because some individuals move to cars. Or the demand for laundromats may decline in response to higher incomes, as households purchase more of their own consumer durables – washers and driers. We use the term inferior good to define these cases: An inferior good is one whose demand declines in response to increasing incomes, whereas a normal good experiences an increase in demand in response to rising incomes.

An inferior good is one whose demand falls in response to higher incomes.

A normal good is one whose demand increases in response to higher incomes.

There is a further sense in which consumer incomes influence demand, and this relates to how the incomes are distributed in the economy. In the discussion above we stated that higher total incomes shift demand curves outwards when goods are normal. But think of the difference in the demand for electronic readers between Portugal and Saudi Arabia. These economies have roughly the same average per-person income, but incomes are distributed more unequally in Saudi Arabia. It does not have a large middle class that can afford electronic readers or iPads, despite the huge wealth held by the elite. In contrast, Portugal has a relatively larger middle class that can afford such goods. Consequently, the distribution of income can be an important determinant of the demand for many commodities and services.

Tastes and networks – hemlines, lapels and homogeneity

While demand functions are drawn on the assumption that tastes are constant, in an evolving world they are not. We are all subject to peer pressure, the fashion industry, marketing, and a desire to maintain our image. If the fashion industry dictates that lapels on men's suits or long skirts are de rigueur for the coming season, some fashion-conscious individuals will discard a large segment of their wardrobe, even though the clothes may be in perfectly good condition: Their demand is influenced by the dictates of current fashion.

Correspondingly, the items that other individuals buy or use frequently determine our own purchases. Businesses frequently decide that all of their employees will have the same type of computer and software on account of network economies: It is easier to communicate if equipment is compatible, and it is less costly to maintain infrastructure where the variety is less.

Expectations – betting on the future

In our natural gas example, if households expected that the price of natural gas was going to stay relatively low for many years – perhaps on account of the discovery of large deposits – then they would be tempted to purchase a gas burning furnace rather than one based upon an alternative fuel. In this example, it is more than the current price that determines choices; the prices that are expected to prevail in the future also determine current demand.

Expectations are particularly important in stock markets. When investors anticipate that corporations will earn high rewards in the future they will buy a stock today. If enough people believe this, the price of the stock will be driven upward on the market, even before profitable earnings are registered.

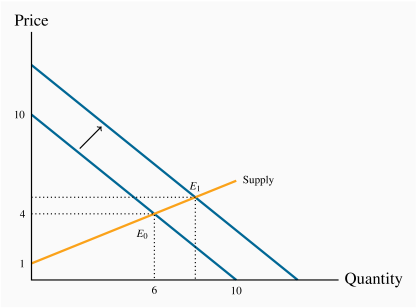

Shifts in demand

The demand curve in Figure 3.2 is drawn for a given level of

other prices, incomes, tastes, and expectations. Movements along the demand

curve reflect solely the impact of different prices for the good in

question, holding other influences constant. But changes in any of these

other factors will change the position of the demand curve. Figure 3.3 illustrates a shift in the demand curve. This shift could

result from a rise in household incomes that increase the quantity demanded

at every price. This is illustrated by an outward shift in the

demand curve. With supply conditions unchanged, there is a new equilibrium

at ![]() , indicating a greater quantity of purchases accompanied by a

higher price. The new equilibrium reflects a change in quantity

supplied and a change in demand.

, indicating a greater quantity of purchases accompanied by a

higher price. The new equilibrium reflects a change in quantity

supplied and a change in demand.

We may well ask why so much emphasis in our diagrams and analysis is placed on the relationship between price and quantity, rather than on the relationship between quantity and its other determinants. The answer is that we could indeed draw diagrams with quantity on the horizontal axis and a measure of one of these other influences on the vertical axis. But the price mechanism plays a very important role. Variations in price are what equilibrate the market. By focusing primarily upon the price, we see the self-correcting mechanism by which the market reacts to excess supply or excess demand.

In addition, this analysis illustrates the method of comparative statics—examining the impact of changing one of the other things that are assumed constant in the supply and demand diagrams.

Comparative static analysis compares an initial equilibrium with a new equilibrium, where the difference is due to a change in one of the other things that lie behind the demand curve or the supply curve.

'Comparative' obviously denotes the idea of a comparison, and static means that we are not in a state of motion. Hence we use these words in conjunction to indicate that we compare one outcome with another, without being concerned too much about the transition from an initial equilibrium to a new equilibrium. The transition would be concerned with dynamics rather than statics. In Figure 3.3 we explain the difference between the points E0 and E1 by indicating that there has been a change in incomes or in the price of a substitute good. We do not attempt to analyze the details of this move or the exact path from E0 to E1.

In the middle of its second mandate, the Bush Administration in the US decided to encourage the production of ethanol – a fuel that is less polluting than gasoline. The target production was 35 billion for 2017 – from a base of 1 billion gallons in 2000. Corn is the principal input in ethanol production. It is also used as animal feed, as a sweetener and as a food for humans. The target was to be met with the help of a subsidy to producers and a tariff on imports of Brazil's sugar-cane based ethanol.

The impact on corn prices was immediate; from a farm-gate price of $2 per bushel in 2005, the price reached the $4 range two years later. In 2012 the price rose temporarily to $7. While other factors were in play - growing incomes and possibly speculation by commodity investors, ethanol is seen as the main price driver: demand for corn increased and the supply could not be increased to keep up with the demand without an increase in price.

The wider impact of these developments was that the prices of virtually all grains increased in tandem with corn: the prices of sorghum and barley increased because of a switch in land use towards corn on account of its profitability.

While farmers benefited from the price rise, consumers – particularly those in less developed economies – experienced a dramatic increase in their basic living costs. Visit the site of the United Nations' Food and Agricultural Organization for an assessment. Since hitting $7 per bushel in 2012, the price has dropped and averaged $3.50 in 2016.

In terms of supply and demand shifts: the demand side has dominated, particularly in the short run. The ethanol drive, combined with secular growth in the demand for food, means that the demand for grains shifted outward faster than the supply. In the period 2013–2016, supply has increased and the price has moderated.

3.5 Non-price influences on supply

To date we have drawn supply curves with an upward slope. Is this a reasonable representation of supply in view of what is frequently observed in markets? We suggested earlier that the various producers of a particular good or service may have different levels of efficiency. If so, only the more efficient producers can make a profit at a low price, whereas at higher prices more producers or suppliers enter the market – producers who may not be as lean and efficient as those who can survive in a lower-price environment. This view of the world yields a positively-sloping supply curve.

As a second example, consider Uber or Lyft taxi drivers. Some drivers may be in serious need of income and may be willing to drive for a low hourly rate. For other individuals driving may be a secondary source of income, and such drivers are less likely to want to drive unless the hourly wage is higher. Consequently if these ride sharing services need a large number of drivers at any one time it may be necessary to pay a higher wage – and charge a higher fare to passengers, to induce more drivers to take their taxis onto the road. This phenomenon corresponds to a positively-sloped supply curve.

In contrast to these two examples, some suppliers simply choose a unique price and let buyers purchase as much as they want at that price. This is the practice of most retailers. For example, the price of Samsung's Galaxy is typically fixed, no matter how many are purchased – and tens of millions are sold at a fixed price when a new model is launched. Apple also sets a price, and buyers purchase as many as they desire at that price. This practice corresponds to a horizontal supply curve: The price does not vary and the market equilibrium occurs where the demand curve intersects this supply curve.

In yet other situations supply is fixed. This happens in auctions. Bidders at the auction simply determine the price to be paid. At a real estate auction a given property is put on the market and the price is determined by the bidding process. In this case the supply of a single property is represented by a vertical supply at a quantity of 1 unit.

Regardless of the type of market we encounter, however, it is safe to assume that supply curves rarely slope downward. So, for the moment, we adopt the stance that supply curves are generally upward sloping – somewhere between the extremes of being vertical or horizontal – as we have drawn them to this point.

Next, we examine those other influences that underlie supply curves. Technology, input costs, the prices of competing goods, expectations and the number of suppliers are the most important.

Technology – computers and fracking

A technological advance may involve an idea that allows more output to be produced with the same inputs, or an equal output with fewer inputs. A good example is just-in-time technology. Before the modern era, virtually all manufacturers kept large stocks of components in their production facilities, but developments in communications and computers at that time made it possible for manufacturers to link directly with their input suppliers. Nowadays auto assembly plants place their order for, say, seat delivery to their local seat supplier well ahead of assembly time. The seats swing into the assembly area hours or minutes before assembly—just in time. The result is that the assembler reduces her seat inventory (an input) and thereby reduces production cost.

Such a technology-induced cost saving is represented by moving the supply curve downward or outward: The supplier is now able and willing to supply the same quantity at a lower price because of the technological innovation. Or, saying the same thing slightly differently, suppliers will supply more at a given price than before.

A second example relates to the extraction of natural gas. The development of 'fracking' means that companies involved in gas recovery can now do so at a lower cost. Hence they are willing to supply any given quantity at a lower price. A third example concerns aluminum cans. Today they weigh a fraction of what they weighed 20 years ago. This is a technology-based cost saving.

Input costs

Input costs can vary independently of technology. For example, a wage negotiation that grants workers a substantial pay raise will increase the cost of production. This is reflected in a leftward, or upward, supply shift: Any quantity supplied is now priced higher; alternatively, suppliers are willing to supply less at the going price.

Production costs may increase as a result of higher required standards in production. As governments implement new safety or product-stress standards, costs may increase. In this instance the increase in costs is not a 'bad' outcome for the buyer. She may be purchasing a higher quality good as a result.

Competing products – Airbnb versus hotels

If competing products improve in quality or fall in price, a supplier may be forced to follow suit. For example, Asus and Dell are constantly watching each other's pricing policies. If Dell brings out a new generation of computers at a lower price, Asus may lower its prices in turn—which is to say that Asus' supply curve will shift downward. Likewise, Samsung and Apple each responds to the other's pricing and technology behaviours. The arrival of new products in the marketplace also impacts the willingness of suppliers to supply goods at a given price. New intermediaries such as Airbnb and Vacation Rentals by Owner have shifted the supply curves of hotel rooms downward.

These are some of the many factors that influence the position of the supply curve in a given market.

Technological developments have had a staggering impact on many price declines. Professor William Nordhaus of Yale University is an expert on measuring technological change. He has examined the trend in the real price of lighting. Originally, light was provided by whale oil and gas lamps and these sources of lumens (the scientific measure of the amount of light produced) were costly. In his research, Professor Nordhaus pieced together evidence on the actual historic cost of light produced at various times, going all the way back to 1800. He found that light in 1800 cost about 100 times more than in 1900, and light in the year 2000 was a fraction of its cost in 1900. A rough calculation suggests that light was five hundred times more expensive at the start of this 200-year period than at the end, and this was before the arrival of LEDs.

In terms of supply and demand analysis, light has been subject to very substantial downward supply shifts. Despite the long-term growth in demand, the technologically-induced supply changes have been the dominant factor in its price determination.

For further information, visit Professor Nordhaus's website in the Department of Economics at Yale University.

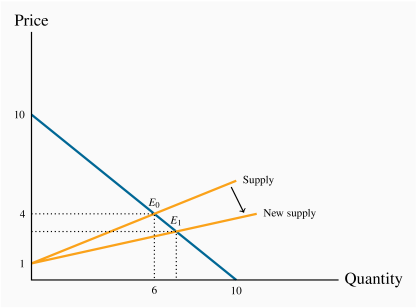

Shifts in supply

Whenever technology changes, or the costs of production change, or the prices of competing products adjust, then one of our ceteris paribus assumptions is violated. Such changes are generally reflected by shifting the supply curve. Figure 3.4 illustrates the impact of the arrival of just-in-time technology. The supply curve shifts, reflecting the ability of suppliers to supply the same output at a reduced price. The resulting new equilibrium price is lower, since production costs have fallen. At this reduced price more gas is traded at a lower price.

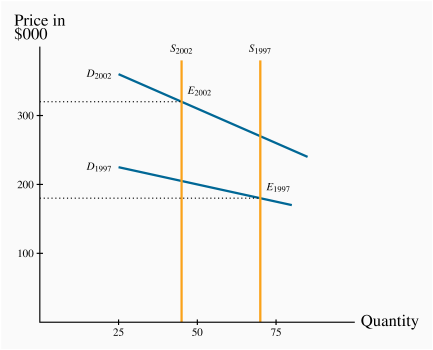

3.6 Simultaneous supply and demand impacts

In the real world, demand and supply frequently shift at the same time. We present such a case in Figure 3.5. It is based upon real estate data describing the housing market in a small Montreal municipality. Vertical curves define the supply side of the market. Such vertical curves mean that a given number of homeowners decide to put their homes on the market, and these suppliers just take whatever price results in the market. In this example, fewer houses were offered for sale in 2002 (less than 50) than in 1997 (more than 70). We are assuming in this market that the houses traded were similar; that is, we are not lumping together mansions with row houses.

During this time period household incomes increased substantially and, also, mortgage rates fell. Both of these developments shifted the demand curve upward/outward: Buyers were willing to pay more for housing in 2002 than in 1997, both because their incomes were on average higher and because they could borrow more cheaply.

The shifts on both sides of the market resulted in a higher average price. And each of these shifts compounded the other: The outward shift in demand would lead to a higher price on its own, and a reduction in supply would do likewise. Hence both forces acted to push up the price in 2002. If, instead, the supply had been greater in 2002 than in 1997 this would have acted to reduce the equilibrium price. And with the demand and supply shifts operating in opposing directions, it is not possible to say in general whether the price would increase or decrease. If the demand shift were strong and the supply shift weak then the demand forces would have dominated and led to a higher price. Conversely, if the supply forces were stronger than the demand forces.

3.7 Market interventions – governments and interest groups

The freely functioning markets that we have developed certainly do not describe all markets. For example, minimum wages characterize the labour market, most agricultural markets have supply restrictions, apartments are subject to rent controls, and blood is not a freely traded market commodity in Canada. In short, price controls and quotas characterize many markets. Price controls are government rules or laws that inhibit the formation of market-determined prices. Quotas are physical restrictions on how much output can be brought to the market.

Price controls are government rules or laws that inhibit the formation of market-determined prices.

Quotas are physical restrictions on output.

Price controls come in the form of either floors or ceilings. Price floors are frequently accompanied by marketing boards.

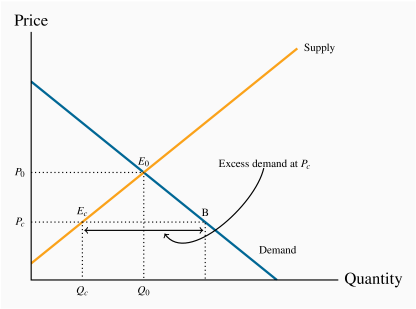

Price ceilings – rental boards

Ceilings mean that suppliers cannot legally charge more than a specific price. Limits on apartment rents are one form of ceiling. In times of emergency – such as flooding or famine, price controls are frequently imposed on foodstuffs, in conjunction with rationing, to ensure that access is not determined by who has the most income. The problem with price ceilings, however, is that they leave demand unsatisfied, and therefore they must be accompanied by some other allocation mechanism.

Consider an environment where, for some reason – perhaps a sudden and unanticipated growth in population – rents increase. Let the resulting equilibrium be defined by the point E0 in Figure 3.6. If the government were to decide that this is an unfair price because it places hardships on low- and middle-income households, it might impose a price limit, or ceiling, of Pc. The problem with such a limit is that excess demand results: Individuals want to rent more apartments than are available in the city. In a free market the price would adjust upward to eliminate the excess demand, but in this controlled environment it cannot. So some other way of allocating the available supply between demanders must evolve.

In reality, most apartments are allocated to those households already occupying them. But what happens when such a resident household decides to purchase a home or move to another city? In a free market, the landlord could increase the rent in accordance with market pressures. But in a controlled market a city's rental tribunal may restrict the annual rent increase to just a couple of percent and the demand may continue to outstrip supply. So how does the stock of apartments get allocated between the potential renters? One allocation method is well known: The existing tenant informs her friends of her plan to move, and the friends are the first to apply to the landlord to occupy the apartment. But that still leaves much unmet demand. If this is a student rental market, students whose parents live nearby may simply return 'home'. Others may chose to move to a part of the city where rents are more affordable.

However, rent controls sometimes yield undesirable outcomes. Rent controls are widely studied in economics, and the consequences are well understood: Landlords tend not to repair or maintain their rental units in good condition if they cannot obtain the rent they believe they are entitled to. Accordingly, the residential rental stock deteriorates. In addition, builders realize that more money is to be made in building condominium units than rental units, or in converting rental units to condominiums. The frequent consequence is thus a reduction in supply and a reduced quality. Market forces are hard to circumvent because, as we emphasized in Chapter 1, economic players react to the incentives they face. These outcomes are examples of what we call the law of unintended consequences.

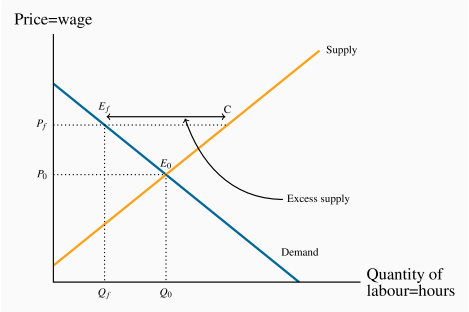

Price floors – minimum wages

An effective price floor sets the price above the market-clearing price. A minimum wage is the most widespread example in the Canadian economy. Provinces each set their own minimum, and it is seen as a way of protecting the well-being of low-skill workers. Such a floor is illustrated in Figure 3.7. The free-market equilibrium is again E0, but the effective market outcome is the combination of price and quantity corresponding to the point Ef at the price floor, Pf. In this instance, there is excess supply equal to the amount EfC.

Note that there is a similarity between the outcomes defined in the floor and ceiling cases: The quantity actually traded is the lesser of the supply quantity and demand quantity at the going price: The short side dominates.

If price floors, in the form of minimum wages, result in some workers going unemployed, why do governments choose to put them in place? The excess supply in this case corresponds to unemployment – more individuals are willing to work for the going wage than buyers (employers) wish to employ. The answer really depends upon the magnitude of the excess supply. In particular, suppose, in Figure 3.7 that the supply and demand curves going through the equilibrium E0 were more 'vertical'. This would result in a smaller excess supply than is represented with the existing supply and demand curves. This would mean in practice that a higher wage could go to workers, making them better off, without causing substantial unemployment. This is the trade off that governments face: With a view to increasing the purchasing power of generally lower-skill individuals, a minimum wage is set, hoping that the negative impact on employment will be small. We will return to this in the next chapter, where we examine the responsiveness of supply and demand curves to different prices.

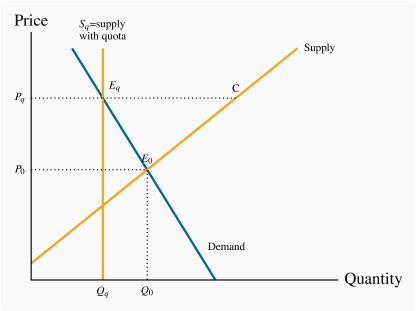

Quotas – agricultural supply

A quota represents the right to supply a specified quantity of a good to the market. It is a means of keeping prices higher than the free-market equilibrium price. As an alternative to imposing a price floor, the government can generate a high price by restricting supply.

Agricultural markets abound with examples. In these markets, farmers can supply only what they are permitted by the quota they hold, and there is usually a market for these quotas. For example, in several Canadian provinces it currently costs in the region of $30,000 to purchase a quota granting the right to sell the milk of one cow. The cost of purchasing quotas can thus easily outstrip the cost of a farm and herd. Canadian cheese importers must pay for the right to import cheese from abroad. Restrictions also apply to poultry. The impact of all of these restrictions is to raise the domestic price above the free market price.

In Figure 3.8, the free-market equilibrium is at E0. In order to raise the price above P0, the government restricts supply to Qq by granting quotas, which permit producers to supply a limited amount of the good in question. This supply is purchased at the price equal to Pq. From the standpoint of farmers, a higher price might be beneficial, even if they get to supply a smaller quantity, provided the amount of revenue they get as a result is as great as the revenue in the free market.

Marketing boards – milk and maple syrup

A marketing board is a means of insuring that a quota or price floor can be maintained. Quotas are frequent in the agriculture sector of the economy. One example is maple syrup in Quebec. The Federation of Maple Syrup Producers of Quebec has the sole right to market maple syrup. All producers must sell their syrup through this marketing board. The board thus has a particular type of power in the market: it has control of the market at the wholesale end, because it is a sole buyer. The Federation increases the total revenue going to producers by artificially restricting the supply to the market. The Federation calculates that by reducing supply and selling it at a higher price, more revenue will accrue to the producers. This is illustrated in Figure 3.8. The market equilibrium is given by E0, but the Federation restricts supply to the quantity Qq, which is sold to buyers at price Pq. To make this possible the total supply must be restricted; otherwise producers would supply the amount given by the point C on the supply curve, and this would result in excess supply in the amount EqC. In order to restrict supply to Qq in total, individual producers are limited in what they can sell to the Federation; they have a quota, which gives them the right to produce and sell no more than a specified amount. This system of quotas is necessary to eliminate the excess supply that would emerge at the above-equilibrium price Pq.

We will return to this topic in Chapter 4. For the moment, to see that this type of revenue-increasing outcome is possible, examine Table 3.1 again. At this equilibrium price of $4 the quantity traded is 6 units, yielding a total expenditure by buyers (revenue to suppliers) of $24. However, if the supply were restricted and a price of $5 were set, the expenditure by buyers (revenue to suppliers) would rise to $25.

3.8 Individual and market functions

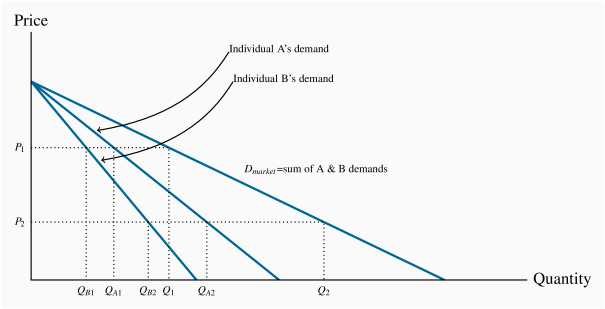

Markets are made up of many individual participants on the demand and supply side. The supply and demand functions that we have worked with in this chapter are those for the total of all participants on each side of the market. But how do we arrive at such market functions when the economy is composed of individuals? We can illustrate how, with the help of Figure 3.9.

To concentrate on the essentials, imagine that there are just two buyers of

chocolate cookies in the economy. A has a stronger preference for cookies than B, so his demand is

greater. To simplify, let the two demands have the same intercept on the

vertical axis. The curves DA and DB indicate how many cookies A and

B, respectively, will buy at each price. The market demand indicates how

much they buy together at any price. Accordingly, at P1, A and B

purchase the quantities ![]() and

and ![]() respectively. Thus

respectively. Thus ![]() .

At a price P2, they purchase

.

At a price P2, they purchase ![]() and

and ![]() . Thus

. Thus ![]() .

The market demand is therefore the horizontal sum of the individual

demands at these prices. In the figure this is defined by

.

The market demand is therefore the horizontal sum of the individual

demands at these prices. In the figure this is defined by ![]() .

.

Market demand: the horizontal sum of individual demands.

3.9 Useful techniques – demand and supply equations

The supply and demand functions, or equations, underlying Table 3.1 and Figure 3.2 can be written in their mathematical form:

A straight line is represented completely by the intercept and slope. In particular, if the variable P is on the vertical axis and Q on the horizontal axis, the straight-line equation relating P and Q is defined by P=a+bQ. Where the line is negatively sloped, as in the demand equation, the parameter b must take a negative value. By observing either the data in Table 3.1 or Figure 3.2 it is clear that the vertical intercept, a, takes a value of $10. The vertical intercept corresponds to a zero-value for the Q variable. Next we can see from Figure 3.2 that the slope (given by the rise over the run) is 10/10 and hence has a value of –1. Accordingly the demand equation takes the form P=10–Q.

On the supply side the price-axis intercept, from either the figure or the table, is clearly 1. The slope is one half, because a two-unit change in quantity is associated with a one-unit change in price. This is a positive relationship obviously so the supply curve can be written as P=1+(1/2)Q.

Where the supply and demand curves intersect is the market equilibrium; that is, the price-quantity combination is the same for both supply and demand where the supply curve takes on the same values as the demand curve. This unique price-quantity combination is obtained by equating the two curves: If Demand=Supply, then

Gathering the terms involving Q to one side and the numerical terms to the other side of the equation results in 9=1.5Q. This implies that the equilibrium quantity must be 6 units. And this quantity must trade at a price of $4. That is, when the price is $4 both the quantity demanded and the quantity supplied take a value of 6 units.

Modelling market interventions using equations

To illustrate the impact of market interventions examined in Section 3.7 on our numerical market model for natural gas, suppose that the government imposes a minimum price of $6 – above the equilibrium price obviously. We can easily determine the quantity supplied and demanded at such a price. Given the supply equation

it follows that at P=6 the quantity supplied is 10. This follows by solving the relationship 6=1+(1/2)Q for the value of Q. Accordingly, suppliers would like to supply 10 units at this price.

Correspondingly on the demand side, given the demand curve

with a price given by ![]() , it must be the case that Q=4. So buyers

would like to buy 4 units at that price: There is excess supply.

But we know that the short side of the market will win out, and so the

actual amount traded at this restricted price will be 4 units.

, it must be the case that Q=4. So buyers

would like to buy 4 units at that price: There is excess supply.

But we know that the short side of the market will win out, and so the

actual amount traded at this restricted price will be 4 units.

Conclusion

We have covered a lot of ground in this chapter. It is intended to open up the vista of economics to the new student in the discipline. Economics is powerful and challenging, and the ideas we have developed here will serve as conceptual foundations for our exploration of the subject. Our next chapter deals with measurement and responsiveness.

Key Terms

Demand is the quantity of a good or service that buyers wish to purchase at each possible price, with all other influences on demand remaining unchanged.

Supply is the quantity of a good or service that sellers are willing to sell at each possible price, with all other influences on supply remaining unchanged.

Quantity demanded defines the amount purchased at a particular price.

Quantity supplied refers to the amount supplied at a particular price.

Equilibrium price: equilibrates the market. It is the price at which quantity demanded equals the quantity supplied.

Excess supply exists when the quantity supplied exceeds the quantity demanded at the going price.

Excess demand exists when the quantity demanded exceeds quantity supplied at the going price.

Short side of the market determines outcomes at prices other than the equilibrium.

Demand curve is a graphical expression of the relationship between price and quantity demanded, with other influences remaining unchanged.

Supply curve is a graphical expression of the relationship between price and quantity supplied, with other influences remaining unchanged.

Substitute goods: when a price reduction (rise) for a related product reduces (increases) the demand for a primary product, it is a substitute for the primary product.

Complementary goods: when a price reduction (rise) for a related product increases (reduces) the demand for a primary product, it is a complement for the primary product.

Inferior good is one whose demand falls in response to higher incomes.

Normal good is one whose demand increases in response to higher incomes.

Comparative static analysis compares an initial equilibrium with a new equilibrium, where the difference is due to a change in one of the other things that lie behind the demand curve or the supply curve.

Price controls are government rules or laws that inhibit the formation of market-determined prices.

Quotas are physical restrictions on output.

Market demand: the horizontal sum of individual demands.

Exercises for Chapter 3

The supply and demand for concert tickets are given in the table below.

| Price ($) | 0 | 4 | 8 | 12 | 16 | 20 | 24 | 28 | 32 | 36 | 40 |

| Quantity demanded | 15 | 14 | 13 | 12 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 |

| Quantity supplied | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 11 |

Plot the supply and demand curves to scale and establish the equilibrium price and quantity.

What is the excess supply or demand when price is $24? When price is $36?

Describe the market adjustments in price induced by these two prices.

Optional: The functions underlying the example in the table are linear and can be presented as P=18+2Q (supply) and P=60–4Q (demand). Solve the two equations for the equilibrium price and quantity values.

Illustrate in a supply/demand diagram, by shifting the demand curve appropriately, the effect on the demand for flights between Calgary and Winnipeg as a result of:

Increasing the annual government subsidy to Via Rail.

Improving the Trans-Canada highway between the two cities.

The arrival of a new budget airline on the scene.

A new trend in US high schools is the widespread use of chewing tobacco. A recent survey indicates that 15 percent of males in upper grades now use it – a figure not far below the use rate for cigarettes. This development came about in response to the widespread implementation by schools of regulations that forbade cigarette smoking on and around school property. Draw a supply-demand equilibrium for each of the cigarette and chewing tobacco markets before and after the introduction of the regulations.

The following table describes the demand and supply conditions for labour.

| Price ($) = wage rate | 0 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | 90 | 100 | 110 | 120 | 130 | 140 | 150 | 160 | 170 |

| Quantity demanded | 1020 | 960 | 900 | 840 | 780 | 720 | 660 | 600 | 540 | 480 | 420 | 360 | 300 | 240 | 180 | 120 | 60 | 0 |

| Quantity supplied | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 60 | 90 | 120 | 150 | 180 | 210 | 240 | 270 | 300 | 330 | 360 |

Graph the functions and find the equilibrium price and quantity by equating demand and supply.

Suppose a price ceiling is established by the government at a price of $120. This price is below the equilibrium price that you have obtained in part (a). Calculate the amount that would be demanded and supplied and then calculate the excess demand.

In Exercise 3.4, suppose that the supply and demand describe an agricultural market rather than a labour market, and the government implements a price floor of $140. This is greater than the equilibrium price.

Estimate the quantity supplied and the quantity demanded at this price, and calculate the excess supply.

Suppose the government instead chose to maintain a price of $140 by implementing a system of quotas. What quantity of quotas should the government make available to the suppliers?

In Exercise 3.5, suppose that, at the minimum price, the government buys up all of the supply that is not demanded, and exports it at a price of $80 per unit. Compute the cost to the government of this operation.

Let us sum two demand curves to obtain a 'market' demand curve. We will suppose there are just two buyers in the market. Each of the individual demand curves has a price intercept of $42. One has a quantity intercept of 126, the other 84.

Draw the demands either to scale or in an Excel spreadsheet, and label the intercepts on both the price and quantity axes.

Determine how much would be purchased in the market at prices $10, $20, and $30.

Optional: Since you know the intercepts of the market (total) demand curve, can you write an equation for it?

In Exercise 3.7 the demand curves had the same price intercept. Suppose instead that the first demand curve has a price intercept of $36 and a quantity intercept of 126; the other individual has a demand curve defined by a price intercept of $42 and a quantity intercept of 84. Graph these curves and illustrate the market demand curve.

Here is an example of a demand curve that is not linear:

| Price ($) | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Quantity demanded | 25 | 100 | 225 | 400 | 625 |

Plot this demand curve to scale or in Excel.

If the supply function in this market is P=2, plot this function in the same diagram.

Determine the equilibrium quantity traded in this market.

The football stadium of the University of the North West Territories has 30 seats. The demand curve for tickets has a price intercept of $36 and a quantity intercept of 72.

Draw the supply and demand curves to scale in a graph or in Excel. (This demand curve has the form

.)

.)Determine the equilibrium admission price, and the amount of revenue generated from ticket sales for each game.

A local alumnus and benefactor offers to install 6 more seats at no cost to the University. Compute the price that would be charged with this new supply and compute the revenue that would accrue at this new equilibrium price. Should the University accept the offer to install the seats?

Redo the previous part of this question, assuming that the initial number of seats is 40, and the University has the option to increase capacity to 46 at no cost to itself. Should the University accept the offer in this case?

Suppose farm workers in Mexico are successful in obtaining a substantial wage increase. Illustrate the effect of this on the price of lettuce in the Canadian winter, using a supply and demand diagram, on the assumption that all lettuce in Canada is imported during its winter.