8: Production and cost

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 108289

Chapter 8: Production and cost

In this chapter we will explore:

| 8.1 | Efficient production |

| 8.2 | Time frames: The short run and the long run |

| 8.3 | Production in the short run |

| 8.4 | Costs in the short run |

| 8.5 | Fixed costs and sunk costs |

| 8.6 | Production and costs in the long run |

| 8.7 | Technological change and globalization |

| 8.8 | Clusters, externalities, learning by doing, and scope economies |

8.1 Efficient production

Firms that fail to operate efficiently seldom survive. They are dominated by their competitors because the latter produce more efficiently and can sell at a lower price. The drive for profitability is everywhere present in the modern economy. Companies that promise more profit, by being more efficient, are valued more highly on the stock exchange. For example: In July of 2015 Google announced that, going forward, it would be more attentive to cost management in its numerous research endeavours that aim to bring new products to the marketplace. This policy, put in place by the Company's new Chief Financial Officer, was welcomed by investors who, as a result, bought up the stock. The Company's stock increased in value by 16% in one day – equivalent to about $50 billion.

The remuneration of managers in virtually all corporations is linked to profitability. Efficient production, a.k.a. cost reduction, is critical to achieving this goal. In this chapter we will examine cost management and efficient production from the ground up – by exploring how a small entrepreneur brings his or her product to market in the most efficient way possible. As we shall see, efficient production and cost minimization amount to the same thing: Cost minimization is the financial reflection of efficient production.

Efficient production is critical in any budget-driven organization, not just in the private sector. Public institutions equally are, and should be, concerned with costs and efficiency.

Entrepreneurs employ factors of production (capital and labour) in order to transform raw materials and other inputs into goods or services. The relationship between output and the inputs used in the production process is called a production function. It specifies how much output can be produced with given combinations of inputs. A production function is not restricted to profit-driven organizations. Municipal road repairs are carried out with labour and capital. Students are educated with teachers, classrooms, computers, and books. Each of these is a production process.

Production function: a technological relationship that specifies how much output can be produced with specific amounts of inputs.

Economists distinguish between two concepts of efficiency: One is technological efficiency; the other is economic efficiency. To illustrate the difference, consider the case of auto assembly: the assembler could produce its vehicles either by using a large number of assembly workers and a plant that has a relatively small amount of machinery, or it could use fewer workers accompanied by more machinery in the form of robots. Each of these processes could be deemed technologically efficient, provided that there is no waste. If the workers without robots are combined with their capital to produce as much as possible, then that production process is technologically efficient. Likewise, in the scenario with robots, if the workers and capital are producing as much as possible, then that process too is efficient in the technological sense.

Technological efficiency means that the maximum output is produced with the given set of inputs.

Economic efficiency is concerned with more than just technological efficiency. Since the entrepreneur's goal is to make profit, she must consider which technologically efficient process best achieves that objective. More broadly, any budget-driven process should focus on being economically efficient, whether in the public or private sector. An economically efficient production structure is the one that produces output at least cost.

Economic efficiency defines a production structure that produces output at least cost.

Auto-assembly plants the world over have moved to using robots during the last two decades. Why? The reason is not that robots were invented 20 years ago; they were invented long before that. The real reason is that, until recently, this technology was not economically efficient. Robots were too expensive; they were not capable of high-precision assembly. But once their cost declined and their accuracy increased they became economically efficient. The development of robots represented technological progress. When this progress reached a critical point, entrepreneurs embraced it.

To illustrate the point further, consider the case of garment assembly. There is no doubt that engineers could make robots capable of joining the pieces of fabric that form garments. This is not beyond our technological abilities. Why, then, do we not have such capital-intensive production processes for garment making, similar to the production process chosen by vehicle producers? The answer is that, while such a concept could be technologically efficient, it would not be economically efficient. It is more profitable to use large amounts of labour and relatively traditional machines to assemble garments, particularly when labour in Asia costs less and the garments can be shipped back to Canada inexpensively. Containerization and scale economies in shipping mean that a garment can be shipped to Canada from Asia for a few cents per unit.

Efficiency in production is not limited to the manufacturing sector. Farmers must choose the optimal combination of labour, capital and fertilizer to use. In the health and education sectors, efficient supply involves choices on how many high- and low-skill workers to employ, how much traditional physical capital to use, how much information technology to use, based upon the productivity and cost of each. Professors and physicians are costly inputs. When they work with new technology (capital) they become more efficient at performing their tasks: It is less costly to have a single professor teach in a 300-seat classroom that is equipped with the latest technology, than have several professors each teaching 60-seat classes with chalk and a blackboard.

8.2 The time frame

We distinguish initially between the short run and the long run. When discussing technological change, we use the term very long run. These concepts have little to do with clocks or calendars; rather, they are defined by the degree of flexibility an entrepreneur or manager has in her production process. A key decision variable is capital.

A customary assumption is that a producer can hire more labour immediately, if necessary, either by taking on new workers (since there are usually some who are unemployed and looking for work), or by getting the existing workers to work longer hours. In contrast, getting new capital in place is usually more time consuming: The entrepreneur may have to place an order for new machinery, which will involve a production and delivery time lag. Or she may have to move to a more spacious location in order to accommodate the added capital. Whether this calendar time is one week, one month, or one year is of no concern to us. We define the long run as a period of sufficient length to enable the entrepreneur to adjust her capital stock, whereas in the short run at least one factor of production is fixed. Note that it matters little whether it is labour or capital that is fixed in the short run. A software development company may be able to install new capital (computing power) instantaneously but have to train new developers. In such a case capital is variable and labour is fixed in the short run. The definition of the short run is that one of the factors is fixed, and in our examples we will assume that it is capital.

Short run: a period during which at least one factor of production is fixed. If capital is fixed, then more output is produced by using additional labour.

Long run: a period of time that is sufficient to enable all factors of production to be adjusted.

Very long run: a period sufficiently long for new technology to develop.

8.3 Production in the short run

Black Diamond Snowboards (BDS) is a start-up snowboard producing enterprise. Its founder has invented a new lamination process that gives extra strength to his boards. He has set up a production line in his garage that has four workstations: Laminating, attaching the steel edge, waxing, and packing.

With this process in place, he must examine how productive his firm can be. After extensive testing, he has determined exactly how his productivity depends upon the number of workers. If he employs only one worker, then that worker must perform several tasks, and will encounter 'down time' between workstations. Extra workers would therefore not only increase the total output; they could, in addition, increase output per worker. He also realizes that once he has employed a critical number of workers, additional workers may not be so productive: Because they will have to share the fixed amount of machinery in his garage, they may have to wait for another worker to finish using a machine. At such a point, the productivity of his plant will begin to fall off, and he may want to consider capital expansion. But for the moment he is constrained to using this particular assembly plant. Testing leads him to formulate the relationship between workers and output that is described in Table 8.1.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Workers | Output | Marginal | Average | Stages of |

| (TP) | product | product | production | |

| (MPL) | (APL) | |||

| 0 | 0 | MPL increasing | ||

| 1 | 15 | 15 | 15 | |

| 2 | 40 | 25 | 20 | |

| 3 | 70 | 30 | 23.3 | |

| 4 | 110 | 40 | 27.5 | |

| 5 | 145 | 35 | 29 | MPL positive and declining |

| 6 | 175 | 30 | 29.2 | |

| 7 | 200 | 25 | 28.6 | |

| 8 | 220 | 20 | 27.5 | |

| 9 | 235 | 15 | 26.1 | |

| 10 | 240 | 5 | 24.0 | |

| 11 | 235 | -5 | 21.4 | MPL negative |

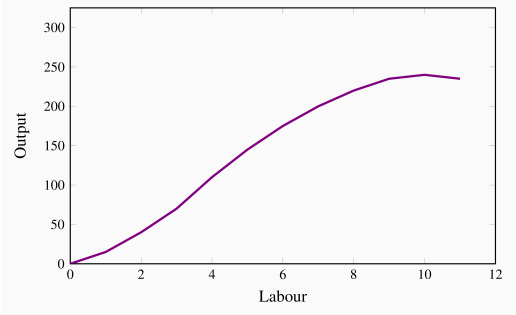

By increasing the number of workers in the plant, BDS produces more boards. The relationship between these two variables in columns 1 and 2 in the table is plotted in Figure 8.1. This is called the total product function (TP), and it defines the output produced with different amounts of labour in a plant of fixed size.

Total product is the relationship between total output produced and the number of workers employed, for a given amount of capital.

This relationship is positive, indicating that more workers produce more boards. But the curve has an interesting pattern. In the initial expansion of employment it becomes progressively steeper – its curvature is slightly convex; following this phase the function's increase becomes progressively less steep – its curvature is concave. These different stages in the TP curve tell us a great deal about productivity in BDS. To see this, consider the additional number of boards produced by each worker. The first worker produces 15. When a second worker is hired, the total product rises to 40, so the additional product attributable to the second worker is 25. A third worker increases output by 30 units, and so on. We refer to this additional output as the marginal product (MP) of an additional worker, because it defines the incremental, or marginal, contribution of the worker. These values are entered in column 3.

More generally the MP of labour is defined as the change in output divided

by the change in the number of units of labour employed. Using, as before,

the Greek capital delta (![]() ) to denote a change, we can define

) to denote a change, we can define

In this example the change in labour is one unit at each stage and hence the marginal product of labour is simply the corresponding change in output. It is also the case that the MPL is the slope of the TP curve – the change in the value on the vertical axis due to a change in the value of the variable on the horizontal axis.

Marginal product of labour is the addition to output produced by each additional worker. It is also the slope of the total product curve.

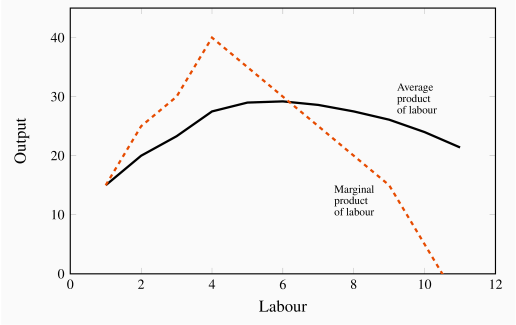

During the initial stage of production expansion, the marginal product of each worker is increasing. It increases from 15 to 40 as BDS moves from having one employee to four employees. This increasing MP is made possible by the fact that each worker is able to spend more time at his workstation, and less time moving between tasks. But, at a certain point in the employment expansion, the MP reaches a maximum and then begins to tail off. At this stage – in the concave region of the TP curve – additional workers continue to produce additional output, but at a diminishing rate. For example, while the fourth worker adds 40 units to output, the fifth worker adds 35, the sixth worker 30, and so on. This declining MP is due to the constraint of a fixed number of machines: All workers must share the same capital. The MP function is plotted in Figure 8.2.

The phenomenon we have just described has the status of a law in economics: The law of diminishing returns states that, in the face of a fixed amount of capital, the contribution of additional units of a variable factor must eventually decline.

Law of diminishing returns: when increments of a variable factor (labour) are added to a fixed amount of another factor (capital), the marginal product of the variable factor must eventually decline.

The relationship between Figures 8.1 and 8.2 should be noted. First, the MPL reaches a maximum at an output of 4 units – where the slope of the TP curve is greatest. The MPL curve remains positive beyond this output, but declines: The TP curve reaches a maximum when the tenth unit of labour is employed. An eleventh unit actually reduces total output; therefore, the MP of this eleventh worker is negative! In Figure 8.2, the MP curve becomes negative at this point. The garage is now so crowded with workers that they are beginning to obstruct the operation of the production process. Thus the producer would never employ an eleventh unit of labour.

Next, consider the information in the fourth column of the table. It defines the average product of labour (APL)—the amount of output produced, on average, by workers at different employment levels:

This function is also plotted in Figure 8.2. Referring to the table: The AP column indicates, for example, that when two units of labour are employed and forty units of output are produced, the average production level of each worker is 20 units (=40/2). When three workers produce 70 units, their average production is 23.3 (=70/3), and so forth. Like the MP function, this one also increases and subsequently decreases, reflecting exactly the same productivity forces that are at work on the MP curve.

Average product of labour is the number of units of output produced per unit of labour at different levels of employment.

The AP and MP functions intersect at the point where the AP is at its peak. This is no accident, and has a simple explanation. Imagine a softball player who is batting .280 coming into today's game—she has been hitting her way onto base 28 percent of the time when batting, so far this season. This is her average product, AP.

In today's game, if she bats .500 (hits her way to base on half of her at-bats), then she will improve her average. Today's batting (MP) at .500 therefore pulls up the season's AP. Accordingly, whenever the MP exceeds the AP, the AP is pulled up. By the same reasoning, if her MP is less than the season average, her average will be pulled down. It follows that the two functions must intersect at the peak of the AP curve. To summarize:

If the MP exceeds the AP, then the AP increases;

If the MP is less than the AP, then the AP declines.

While the owner of BDS may understand his productivity relations, his ultimate goal is to make profit, and for this he must figure out how productivity translates into cost.

8.4 Costs in the short run

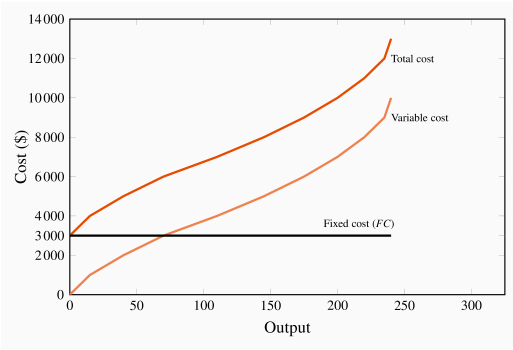

The cost structure for the production of snowboards at Black Diamond is illustrated in Table 8.2. Employees are skilled and are paid a weekly wage of $1,000. The cost of capital is $3,000 and it is fixed, which means that it does not vary with output. As in Table 8.1, the number of employees and the output are given in the first two columns. The following three columns define the capital costs, the labour costs, and the sum of these in producing different levels of output. We use the terms fixed, variable, and total costs to define the cost structure of a firm. Fixed costs do not vary with output, whereas variable costs do, and total costs are the sum of fixed and variable costs. To keep this example as simple as possible, we will ignore the cost of raw materials. We could add an additional column of costs, but doing so will not change the conclusions.

| Workers | Output | Capital | Labour | Total | Average | Average | Average | Marginal |

| cost | cost | costs | fixed | variable | total | cost | ||

| fixed | variable | cost | cost | cost | ||||

| 0 | 0 | 3,000 | 0 | 3,000 | ||||

| 1 | 15 | 3,000 | 1,000 | 4,000 | 200.0 | 66.7 | 266.7 | 66.7 |

| 2 | 40 | 3,000 | 2,000 | 5,000 | 75.0 | 50.0 | 125.0 | 40.0 |

| 3 | 70 | 3,000 | 3,000 | 6,000 | 42.9 | 42.9 | 85.7 | 33.3 |

| 4 | 110 | 3,000 | 4,000 | 7,000 | 27.3 | 36.4 | 63.6 | 25.0 |

| 5 | 145 | 3,000 | 5,000 | 8,000 | 20.7 | 34.5 | 55.2 | 28.6 |

| 6 | 175 | 3,000 | 6,000 | 9,000 | 17.1 | 34.3 | 51.4 | 33.3 |

| 7 | 200 | 3,000 | 7,000 | 10,000 | 15.0 | 35.0 | 50.0 | 40.0 |

| 8 | 220 | 3,000 | 8,000 | 11,000 | 13.6 | 36.4 | 50.0 | 50.0 |

| 9 | 235 | 3,000 | 9,000 | 12,000 | 12.8 | 38.3 | 51.1 | 66.7 |

| 10 | 240 | 3,000 | 10,000 | 13,000 | 12.5 | 41.7 | 54.2 | 200.0 |

Fixed costs are costs that are independent of the level of output.

Variable costs are related to the output produced.

Total cost is the sum of fixed cost and variable cost.

Total costs are illustrated in Figure 8.3 as the vertical sum of variable and fixed costs. For example, Table 8.2 indicates that the total cost of producing 220 units of output is the sum of $3,000 in fixed costs plus $8,000 in variable costs. Therefore, at the output level 220 on the horizontal axis in Figure 8.3, the sum of the cost components yields a value of $11,000 that forms one point on the total cost curve. Performing a similar calculation for every possible output yields a series of points that together form the complete total cost curve.

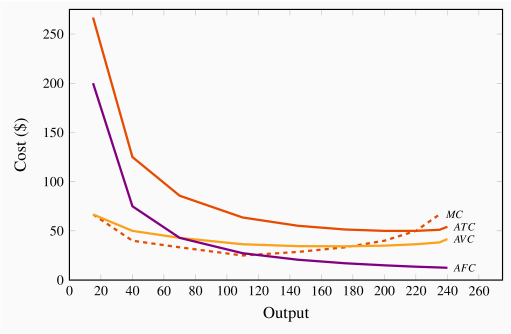

Average costs are given in the next three columns of Table 8.2. Average cost is the cost per unit of output, and we can define an average cost corresponding to each of the fixed, variable, and total costs defined above. Average fixed cost (AFC) is the total fixed cost divided by output; average variable cost (AVC) is the total variable cost divided by output; and average total cost (ATC) is the total cost divided by output.

| AFC | |

| AVC | |

| ATC | =AFC+AVC |

Average fixed cost is the total fixed cost per unit of output.

Average variable cost is the total variable cost per unit of output.

Average total cost is the sum of all costs per unit of output.

The productivity-cost relationship

Consider the average variable cost - average product relationship, as developed in column 7 of Table 8.2; its corresponding variable cost curve is plotted in Figure 8.4. In this example, AVC first decreases and then increases. The intuition behind its shape is straightforward (and realistic) if you have understood why productivity varies in the short run: The variable cost, which represents the cost of labour, is constant per unit of labour, because the wage paid to each worker does not change. However, each worker's productivity varies. Initially, when we hire more workers, they become more productive, perhaps because they have less 'down time' in switching between tasks. This means that the labour costs per snowboard must decline. At some point, however, the law of diminishing returns sets in: As before, each additional worker is paid a constant amount, but as productivity declines the labour cost per snowboard increases.

In this numerical example the AP is at a maximum when six units of labour are employed and output is 175. This is also the point where the AVC is at a minimum. This maximum/minimum relationship is also illustrated in Figures 8.2 and 8.4.

Now consider the marginal cost - marginal product relationship. The marginal cost (MC) defines the cost of producing one more

unit of output. In Table 8.2, the marginal cost of

output is given in the final column. It is the additional cost of production

divided by the additional number of units produced. For example, in going

from 15 units of output to 40, total costs increase from $4,000 to $5,000.

The MC is the cost of those additional units divided by the number of

additional units. In this range of output, MC is ![]() . We

could also calculate the MC as the addition to variable costs rather than

the addition to total costs, because the addition to each is the

same—fixed costs are fixed. Hence:

. We

could also calculate the MC as the addition to variable costs rather than

the addition to total costs, because the addition to each is the

same—fixed costs are fixed. Hence:

| MC | |

Marginal cost of production is the cost of producing each additional unit of output.

Just as the behaviour of the AVC curve is determined by the AP curve, so too the behaviour of the MC is determined by the MP curve. When the MP of an additional worker exceeds the MP of the previous worker, this implies that the cost of the additional output produced by the last worker hired must be declining. To summarize:

If the marginal product of labour increases, then the marginal cost of output declines;

If the marginal product of labour declines, then the marginal cost of output increases.

In our example, the ![]() reaches a maximum when the fourth unit of

labour is employed (or 110 units of output are produced), and this also is

where the MC is at a minimum. This illustrates that the marginal

cost reaches a minimum at the output level where the marginal product

reaches a maximum.

reaches a maximum when the fourth unit of

labour is employed (or 110 units of output are produced), and this also is

where the MC is at a minimum. This illustrates that the marginal

cost reaches a minimum at the output level where the marginal product

reaches a maximum.

The average total cost is the sum of the fixed cost per unit of output and the variable cost per unit of output. Typically, fixed costs are the dominant component of total costs at low output levels, but become less dominant at higher output levels. Unlike average variable costs, note that the average fixed cost must always decline with output, because a fixed cost is being spread over more units of output. Hence, when the ATC curve eventually increases, it is because the increasing variable cost component eventually dominates the declining AFC component. In our example, this occurs when output increases from 220 units (8 workers) to 235 (9 workers).

Finally, observe the interrelationship between the MC curve on the one hand and the ATC and AVC on the other. Note from Figure 8.4 that the MC cuts the AVC and the ATC at the minimum point of each of the latter. The logic behind this pattern is analogous to the logic of the relationship between marginal and average product curves: When the cost of an additional unit of output is less than the average, this reduces the average cost; whereas, if the cost of an additional unit of output is above the average, this raises the average cost. This must hold true regardless of whether we relate the MC to the ATC or the AVC.

When the marginal cost is less than the average cost, the average cost must decline;

When the marginal cost exceeds the average cost, the average cost must increase.

Notation: We use both the abbreviations ![]() and

and

![]() to denote average total cost. The term 'average

cost' is understood in economics to include both fixed and variable costs.

to denote average total cost. The term 'average

cost' is understood in economics to include both fixed and variable costs.

Teams and services

The choice faced by the producer in the example above is slightly 'stylized', yet it still provides an appropriate rule for analyzing hiring decisions. In practice, it is quite difficult to isolate or identify the marginal product of an individual worker. One reason is that individuals work in teams within organizations. The accounting department, the marketing department, the sales department, the assembly unit, the chief executive's unit are all composed of teams. Adding one more person to human resources may have no impact on the number of units of output produced by the company in a measurable way, but it may influence worker morale and hence longer-term productivity. Nonetheless, if we consider expanding, or contracting, any one department within an organization, management can attempt to estimate the net impact of additional hires (or layoffs) on the contribution of each team to the firm's profitability. Adding a person in marketing may increase sales, laying off a person in research and development may reduce costs by more than it reduces future value to the firm. In practice this is what firms do: they attempt to assess the contribution of each team in their organization to costs and revenues, and on that basis determine the appropriate number of employees.

The manufacturing sector of the macro economy is dominated, sizewise, by the services sector. But the logic that drives hiring decisions, as developed above, applies equally to services. For example, how does a law firm determine the optimal number of paralegals to employ per lawyer? How many nurses are required to support a surgeon? How many university professors are required to teach a given number of students?

All of these employment decisions involve optimization at the margin. The goal of the decision maker is not always profit, but she should attempt to estimate the cost and value of adding personnel at the margin.

8.5 Fixed costs and sunk costs

The distinction between fixed and variable costs is important for producers who are not making a profit. If a producer has committed himself to setting up a plant, then he has made a decision to incur a fixed cost. Having done this, he must now decide on a production strategy that will maximize profit. However, the price that consumers are willing to pay may not be sufficient to yield a profit. So, if Black Diamond Snowboards cannot make a profit, should it shut down? The answer is that if it can cover its variable costs, having already incurred its fixed costs, it should stay in production, at least temporarily. By covering the variable cost of its operation, Black Diamond is at least earning some return. A sunk cost is a fixed cost that has already been incurred and cannot be recovered. But if the pressures of the marketplace are so great that the total costs cannot be covered in the longer run, then this is not a profitable business and the firm should close its doors.

Is a fixed cost always a sunk cost? No: Any production that involves capital will incur a fixed cost component. Such capital can be financed in several ways however: It might be financed on a very short-term lease basis, or it might have been purchased by the entrepreneur. If it is leased on a month-to-month basis, an unprofitable entrepreneur who can only cover variable costs (and who does not foresee better market conditions ahead) can exit the industry quickly – by not renewing the lease on the capital. But an individual who has actually purchased equipment that cannot readily be resold has essentially sunk money into the fixed cost component of his production. This entrepreneur should continue to produce as long as he can cover variable costs.

Sunk cost is a fixed cost that has already been incurred and cannot be recovered, even by producing a zero output.

R & D as a sunk cost

Sunk costs in the modern era are frequently in the form of research and development costs, not the cost of building a plant or purchasing machinery. The prototypical example is the pharmaceutical industry, where it is becoming progressively more challenging to make new drug breakthroughs – both because the 'easier' breakthroughs have already been made, and because it is necessary to meet tighter safety conditions attaching to new drugs. Research frequently leads to drugs that are not sufficiently effective in meeting their target. As a consequence, the pharmaceutical sector regularly writes off hundreds of millions of dollars of lost sunk costs – unfruitful research and development.

Finally, we need to keep in mind the opportunity costs of running the business. The owner pays himself a salary, and ultimately he must recognize that the survival of the business should not depend upon his drawing a salary that is less than his opportunity cost. As developed in Section 7.2, if he underpays himself in order to avoid shutting down, he might be better off in the long run to close the business and earn his opportunity cost elsewhere in the marketplace.

A dynamic setting

We need to ask why it might be possible to cover all costs in a longer run horizon, while in the near-term costs are not covered. The principal reason is that demand may grow, particularly for a new product. For example, in 2019 numerous cannabis producing firms were listed on the Canadian Securities Exchange, and collectively were valued at about fifty billion dollars. None had revenues that covered costs, yet investors poured money into this sector. Investors evidently envisaged that the market for legal cannabis would grow. As of 2020 it appears that these investors were excessively optimistic. Sales growth has been slow and stock valuations have plummeted.

8.6 Long-run production and costs

The snowboard manufacturer we portray produces a relatively low level of output; in reality, millions of snowboards are produced each year in the global market. Black Diamond Snowboards may have hoped to get a start by going after a local market—the "free-ride" teenagers at Mont Sainte Anne in Quebec or at Fernie in British Columbia. If this business takes off, the owner must increase production, take the business out of his garage and set up a larger-scale operation. But how will this affect his cost structure? Will he be able to produce boards at a lower cost than when he was producing a very limited number of boards each season? Real-world experience would indicate yes.

Production costs almost always decline when the scale of the operation initially increases. We refer to this phenomenon simply as economies of scale. There are several reasons why scale economies are encountered. One is that production flows can be organized in a more efficient manner when more is being produced. Another is that the opportunity to make greater use of task specialization presents itself; for example, Black Diamond Snowboards may be able to subdivide tasks within the laminating and packaging stations. With a larger operating scale the replacement of labor with capital may be economically efficient. If scale economies do define the real world, then a bigger plant—one that is geared to produce a higher level of output—should have an average total cost curve that is "lower" than the cost curve corresponding to the smaller scale of operation we considered in the example above.

Average costs in the long run

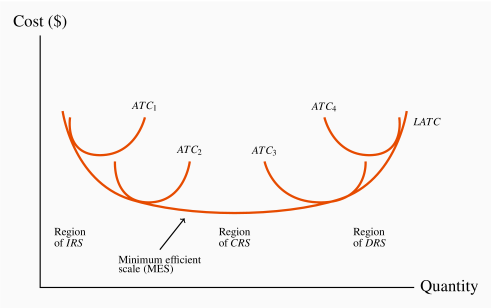

Figure 8.5 illustrates a possible relationship between

the ATC curves for four different scales of operation. ![]() is the

average total cost curve associated with a small-sized plant; think of it as

the plant built in the entrepreneur's garage.

is the

average total cost curve associated with a small-sized plant; think of it as

the plant built in the entrepreneur's garage. ![]() is associated with a

somewhat larger plant, perhaps one she has put together in a rented

industrial or commercial space. The further a cost curve is located to the

right of the diagram the larger the production facility it defines, given

that output is measured on the horizontal axis. If there are economies

associated with a larger scale of operation, then the average costs

associated with producing larger outputs in a larger plant should be lower

than the average costs associated with lower outputs in a smaller plant,

assuming that the plants are producing the output levels they were designed

to produce. For this reason, the cost curve

is associated with a

somewhat larger plant, perhaps one she has put together in a rented

industrial or commercial space. The further a cost curve is located to the

right of the diagram the larger the production facility it defines, given

that output is measured on the horizontal axis. If there are economies

associated with a larger scale of operation, then the average costs

associated with producing larger outputs in a larger plant should be lower

than the average costs associated with lower outputs in a smaller plant,

assuming that the plants are producing the output levels they were designed

to produce. For this reason, the cost curve ![]() and the cost curve

and the cost curve

![]() each have a segment that is lower than the lowest segment on

each have a segment that is lower than the lowest segment on

![]() . However, in Figure 8.5 the cost curve

. However, in Figure 8.5 the cost curve ![]() has moved upwards. What behaviours are implied here?

has moved upwards. What behaviours are implied here?

In many production environments, beyond some large scale of operation, it

becomes increasingly difficult to reap further cost reductions from

specialization, organizational economies, or marketing economies. At such a

point, the scale economies are effectively exhausted, and larger plant sizes

no longer give rise to lower (short-run) ATC curves. This is reflected in the

similarity of the ![]() and the

and the ![]() curves. The pattern suggests

that we have almost exhausted the possibilities of further scale advantages once we

build a plant size corresponding to

curves. The pattern suggests

that we have almost exhausted the possibilities of further scale advantages once we

build a plant size corresponding to ![]() . Consider next what is implied by the

position of the

. Consider next what is implied by the

position of the ![]() curve relative to the

curve relative to the ![]() and

and ![]() curves. The relatively higher position of the

curves. The relatively higher position of the ![]() curve implies that

unit costs will be higher in a yet larger plant. Stated differently: If we

increase the scale of this firm to extremely high output levels, we are

actually encountering diseconomies of scale. Diseconomies of

scale imply that unit costs increase as a result of the firm's becoming too

large: Perhaps co-ordination difficulties have set in at the very high

output levels, or quality-control monitoring costs have risen. These

coordination and management difficulties are reflected in increasing unit

costs in the long run.

curve implies that

unit costs will be higher in a yet larger plant. Stated differently: If we

increase the scale of this firm to extremely high output levels, we are

actually encountering diseconomies of scale. Diseconomies of

scale imply that unit costs increase as a result of the firm's becoming too

large: Perhaps co-ordination difficulties have set in at the very high

output levels, or quality-control monitoring costs have risen. These

coordination and management difficulties are reflected in increasing unit

costs in the long run.

The terms increasing, constant, and decreasing returns to scale underlie the concepts of scale economies and diseconomies: Increasing returns to scale (IRS) implies that, when all inputs are increased by a given proportion, output increases more than proportionately. Constant returns to scale (CRS) implies that output increases in direct proportion to an equal proportionate increase in all inputs. Decreasing returns to scale (DRS) implies that an equal proportionate increase in all inputs leads to a less than proportionate increase in output.

Increasing returns to scale implies that, when all inputs are increased by a given proportion, output increases more than proportionately.

Constant returns to scale implies that output increases in direct proportion to an equal proportionate increase in all inputs.

Decreasing returns to scale implies that an equal proportionate increase in all inputs leads to a less than proportionate increase in output.

These are pure production function relationships, but, if the prices of inputs are fixed for producers, they translate directly into the various cost structures illustrated in Figure 8.5. For example, if a 40% increase in capital and labour use allows for better production flows than when in the smaller plant, and therefore yields more than a 40% increase in output, this implies that the cost per snowboard produced must fall in the new plant. In contrast, if a 40% increase in capital and labour leads to say just a 30% increase in output, then the cost per snowboard in the new larger plant must be higher. Between these extremes, there may be a range of relatively constant unit costs, corresponding to where the production relation is subject to constant returns to scale. In Figure 8.5, the falling unit costs output region has increasing returns to scale, the region that has relatively constant unit costs has constant returns to scale, and the increasing cost region has decreasing returns to scale.

Increasing returns to scale characterize businesses with large initial costs and relatively low costs of producing each unit of output. Computer chip manufacturers, pharmaceutical manufacturers, vehicle rental agencies, booking agencies such as booking.com or hotels.com, intermediaries such as airbnb.com, even brewers, all benefit from scale economies. In the beer market, brewing, bottling and shipping are all low-cost operations relative to the capital cost of setting up a brewery. Consequently, we observe surprisingly few breweries in any brewing company, even in large land-mass economies such as Canada or the US.

In addition to the four short-run average total cost curves, Figure 8.5 contains a curve that forms an envelope around the bottom of these short-run average cost curves. This envelope is the long-run average total cost (LATC) curve, because it defines average cost as we move from one plant size to another. Remember that in the long run both labour and capital are variable, and as we move from one short-run average cost curve to another, that is exactly what happens—all factors of production are variable. Hence, the collection of short-run cost curves in Figure 8.5 provides the ingredients for a long-run average total cost curve1.

Long-run average total cost is the lower envelope of all the short-run ATC curves.

The particular range of output on the LATC where it begins to flatten out is called the range of minimum efficient scale. This is an important concept in industrial policy, as we shall see in later chapters. At such an output level, the producer has expanded sufficiently to take advantage of virtually all the scale economies available.

Minimum efficient scale defines a threshold size of operation such that scale

economies are almost exhausted.

In view of this discussion and the shape of the LATC in Figure 8.5, it is obvious that economies of scale can also be defined in terms of the curvature of the LATC. Where the LATC declines there are IRS, where the LATC is flat there are CRS, where the LATC slopes upward there are DRS.

| Q | | | | | | |

| 20 | 50 | 30 | 80 | 100 | 25 | 125 |

| 40 | 25 | 30 | 55 | 50 | 25 | 75 |

| 60 | 16.67 | 30 | 46.67 | 33.33 | 25 | 58.33 |

| 80 | 12.5 | 30 | 42.5 | 25 | 25 | 50 |

| 100 | 10 | 30 | 40 | 20 | 25 | 45 |

| 120 | 8.33 | 30 | 38.33 | 16.67 | 25 | 41.67 |

| 140 | 7.14 | 30 | 37.14 | 14.29 | 25 | 39.29 |

| 160 | 6.25 | 30 | 36.25 | 12.5 | 25 | 37.5 |

| 180 | 5.56 | 30 | 35.56 | 11.11 | 25 | 36.11 |

| 200 | 5 | 30 | 35 | 10 | 25 | 35 |

| 220 | 4.55 | 30 | 34.55 | 9.09 | 25 | 34.09 |

| 240 | 4.17 | 30 | 34.17 | 8.33 | 25 | 33.33 |

| 260 | 3.85 | 30 | 33.85 | 7.69 | 25 | 32.69 |

| 280 | 3.57 | 30 | 33.57 | 7.14 | 25 | 32.14 |

Long-run costs – a simple numerical example

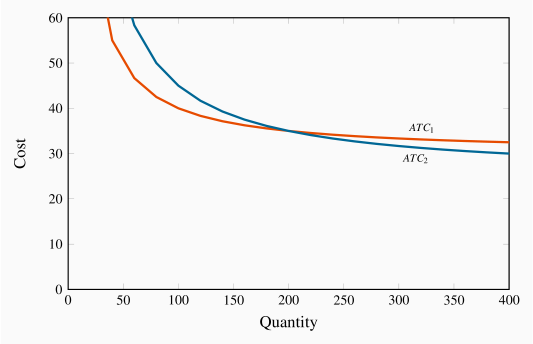

Kitt is an automobile designer specializing in the production of off-road vehicles sold to a small clientele. He has a choice of two (and only two) plant sizes; one involving mainly labour and the other employing robots extensively. The set-up (i.e. fixed) costs of these two assembly plants are $1 million and $2 million respectively. The advantage to having the more costly plant is that the pure production costs (variable costs) are less. The cost components are defined in Table 8.3. The variable cost (equal to the marginal cost here) is $30,000 in the plant that relies primarily on labour, and $25,000 in the plant that has robots. The ATC for each plant size is the sum of AFC and AVC. The AFC declines as the fixed cost is spread over more units produced. The variable cost per unit is constant in each case. By comparing the fourth and final columns, it is clear that the robot-intensive plant has lower costs if it produces a large number of vehicles. At an output of 200 vehicles the average costs in each plant are identical: The higher fixed costs associated with the robots are exactly offset by the lower variable costs at this output level.

The ATC curve corresponding to each plant size is given in Figure 8.6. There are two short-run ATC curves. The positions of these curves indicate that if the manufacturer believes he can produce at least 200 vehicles his unit costs will be less with the plant involving robots; but at output levels less than this his unit costs would be less in the labour-intensive plant.

The long-run average cost curve for this producer is the lower envelope of

these two cost curves: ATC1 up to output 200 and ATC2 thereafter.

Two features of this example are to be noted. First we do not encounter

decreasing returns – the LATC curve never increases. ATC1 tends asymptotically to a lower bound of ![]() , while ATC2 tends towards

, while ATC2 tends towards ![]() . Second, in the

interests of simplicity we have assumed just two plant sizes are possible.

With more possibilities on the introduction of robots we could imagine more

short-run ATC curves which would form the lower-envelope LATC.

. Second, in the

interests of simplicity we have assumed just two plant sizes are possible.

With more possibilities on the introduction of robots we could imagine more

short-run ATC curves which would form the lower-envelope LATC.

8.7 Technological change: globalization and localization

Technological change represents innovation that can reduce the cost of production or bring new products on line. As stated earlier, the very long run is a period that is sufficiently long for new technology to evolve and be implemented.

Technological change represents innovation that can reduce the cost of production or bring new products on line.

Technological change has had an enormous impact on economic life for several centuries. It is not something that is defined in terms of the recent telecommunications revolution. The industrial revolution began in eighteenth century Britain. It was accompanied by a less well-recognized, but equally important, agricultural revolution. The improvement in cultivation technology, and ensuing higher yields, freed up enough labour to populate the factories that were the core of the industrial revolution2. The development and spread of mechanical power dominated the nineteenth century, and the mass production line of Henry Ford in autos or Andrew Carnegie in steel heralded in the twentieth century.

Globalization

The modern communications revolution has reduced costs, just like its predecessors. But it has also greatly sped up globalization, the increasing integration of national markets.

Globalization is the tendency for international markets to be ever more integrated.

Globalization has several drivers: lower transportation and communication costs; reduced barriers to trade and capital mobility; the spread of new technologies that facilitate cost and quality control; different wage rates between developed and less developed economies. New technology and better communications have been critical in both increasing the minimum efficient scale of operation and reducing diseconomies of scale; they facilitate the efficient management of large companies.

The continued reduction in trade barriers in the post-World War II era has also meant that the effective marketplace has become the globe rather than the national economy for many products. Companies like Apple, Microsoft, and Facebook are visible worldwide. Globalization has been accompanied by the collapse of the Soviet Union, the adoption of an outward looking philosophy on the part of China, and an increasing role for the market place in India. These developments together have facilitated the outsourcing of much of the West's manufacturing to lower-wage economies.

But new technology not only helps existing companies grow large; it also enables new ones to start up. It is now cheaper for small producers to manage their inventories and maintain contact with their own suppliers.

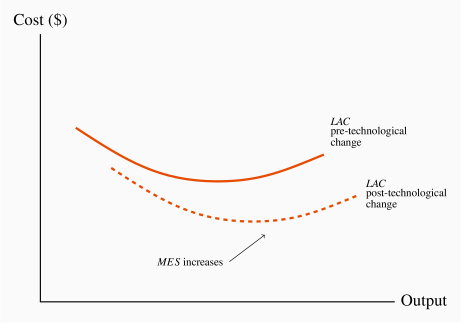

The impact of technology is to reduce the cost of production, hence it will lower the average cost curve in both the short and long run. First, decreasing returns to scale become less probable due to improved communications, so the upward sloping section of the LRAC curve may disappear altogether. Second, capital costs are now lower than in earlier times, because much modern technology has transformed some fixed costs into variable cost: Both software and hardware functions can be subcontracted to specialty firms, who in turn may use cloud computing services, and it is thus no longer necessary to have a substantial in-house computing department. The use of almost-free software such as Skype, Hangouts and WhatsApp reduces communication costs. Advertising on social media is more effective and less costly than in traditional hard-print form. Hiring may be cheaper through LinkedIn than through a traditional human resources department. These developments may actually reduce the minimum efficient scale of operation because they reduce the need for large outlays on fixed capital. On the other hand, changes in technology may induce producers to use more capital and less labor, with the passage of time. That would increase the minimum efficient scale. An example of this phenomenon is in mining, or tunnel drilling, where capital investment per worker is greater than when technology was less developed. A further example is the introduction of robotic assistants in Amazon warehouses. In these scenarios the minimum efficient scale should increase, and that is illustrated in Figure 8.7.

The local diffusion of technology

The impacts of technological change are not just evident in a global context. Technological change impacts every sector of the domestic economy. For example, the modern era in dentistry sees specialists in root canals (endodentists) performing root canals in the space of a single hour with the help of new technology; dental implants into bone, as an alternative to dentures, are commonplace; crowns can be machined with little human intervention; and X-rays are now performed with about one hundredth of the power formerly required. These technologies spread and are adopted through several channels. Dental practices do not usually compete on the basis of price, but if they do not adopt best practices and new technologies, then community word of mouth will see patients shifting to more efficient operators.

Some technological developments are protected by patents. But patent protection rarely inhibits new and more efficient practices that in some way mimic patent breakthroughs.

8.8 Clusters, learning by doing, scope economies

Clusters

The phenomenon of a grouping of firms that specialize in producing related products is called a cluster. For example, Ottawa has more than its share of software development firms; Montreal has a disproportionate share of Canada's pharmaceutical producers and electronic game developers; Calgary has its 'oil patch'; Hollywood has movies; Toronto is Canada's financial capital, San Francisco and Seattle are leaders in new electronic products. Provincial and state capitals have most of their province's bureaucracy. Clusters give rise to externalities, frequently in the form of ideas that flow between firms, which in turn result in cost reductions and new products.

Cluster: a group of firms producing similar products, or engaged in similar research.

The most famous example of clustering is Silicon Valley, surrounding San Francisco, in California, the original high-tech cluster. The presence of a large group of firms with a common focus serves as a signal to workers with the right skill set that they are in demand in such a region. Furthermore, if these clusters are research oriented, as they frequently are, then knowledge spillovers benefit virtually all of the contiguous firms; when workers change employers, they bring their previously-learned skills with them; on social occasions, friends may chat about their work and interests and share ideas. This is a positive externality.

Learning by doing

Learning from production-related experiences frequently reduces costs: The accumulation of knowledge that is associated with having produced a large volume of output over a considerable time period enables managers to implement more efficient production methods and avoid errors. We give the term learning by doing to this accumulation of knowledge.

Examples abound, but the best known may be the continual improvement in the capacity of computer chips, whose efficiency has doubled about every eighteen months for several decades – a phenomenon known as Moore's Law. As Intel Corporation continues to produce chips it learns how to produce each succeeding generation of chips at lower cost. Past experience is key. Economies of scale and learning by doing therefore may not be independent: Large firms usually require time to grow or to attain a dominant role in their market, and this time and experience enables them to produce at lower cost. This lower cost in turn can solidify their market position further.

Learning by doing can reduce costs. A longer history of production enables firms to accumulate knowledge and thereby implement more efficient production processes.

Economies of scope

Economies of scope define a production process if the production of multiple products results in lower unit costs per product than if those products were produced alone. Scope economies, therefore, define the returns or cost reductions associated with broadening a firm's product range.

Corporations like Proctor and Gamble do not produce a single product in their health line; rather, they produce first aid, dental care, and baby care products. Cable companies offer their customers TV, high-speed Internet, and telephone services either individually or packaged. A central component of some new-economy multi-product firms is a technology platform that can be used for multiple purposes. We shall analyze the operation of these firms in more detail in Chapter 11.

Economies of scope occur if the unit cost of producing particular products is less when combined with the production of other products than when produced alone.

A platform is a hardware-cum-software capital installation that has multiple production capabilities

Conclusion

Efficient production is critical to the survival of firms. Firms that do not adopt the most efficient production methods are likely to be left behind by their competitors. Efficiency translates into cost considerations, and the structure of costs in turn has a major impact on market type. Some sectors of the economy have very many firms (the restaurant business or the dry-cleaning business), whereas other sectors have few (internet providers or airlines). We will see in the following chapters how market structures depend critically upon the concept of scale economies that we have developed here.

Key Terms

Production function: a technological relationship that specifies how much output can be produced with specific amounts of inputs.

Technological efficiency means that the maximum output is produced with the given set of inputs.

Economic efficiency defines a production structure that produces output at least cost.

Short run: a period during which at least one factor of production is fixed. If capital is fixed, then more output is produced by using additional labour.

Long run: a period of time that is sufficient to enable all factors of production to be adjusted.

Very long run: a period sufficiently long for new technology to develop.

Total product is the relationship between total output produced and the number of workers employed, for a given amount of capital.

Marginal product of labour is the addition to output produced by each additional worker. It is also the slope of the total product curve.

Law of diminishing returns: when increments of a variable factor (labour) are added to a fixed amount of another factor (capital), the marginal product of the variable factor must eventually decline.

Average product of labour is the number of units of output produced per unit of labour at different levels of employment.

Fixed costs are costs that are independent of the level of output.

Variable costs are related to the output produced.

Total cost is the sum of fixed cost and variable cost.

Average fixed cost is the total fixed cost per unit of output.

Average variable cost is the total variable cost per unit of output.

Average total cost is the sum of all costs per unit of output.

Marginal cost of production is the cost of producing each additional unit of output.

Sunk cost is a fixed cost that has already been incurred and cannot be recovered, even by producing a zero output.

Increasing returns to scale implies that, when all inputs are increased by a given proportion, output increases more than proportionately.

Constant returns to scale implies that output increases in direct proportion to an equal proportionate increase in all inputs.

Decreasing returns to scale implies that an equal proportionate increase in all inputs leads to a less than proportionate increase in output.

Long-run average total cost is the lower envelope of all the short-run ATC curves.

Minimum efficient scale defines a threshold size of operation such that scale economies are almost exhausted.

Long-run marginal cost is the increment in cost associated with producing one more unit of output when all inputs are adjusted in a cost minimizing manner.

Technological change represents innovation that can reduce the cost of production or bring new products on line.

Globalization is the tendency for international markets to be ever more integrated.

Cluster: a group of firms producing similar products, or engaged in similar research.

Learning by doing can reduce costs. A longer history of production enables firms to accumulate knowledge and thereby implement more efficient production processes.

Economies of scope occur if the unit cost of producing particular products is less when combined with the production of other products than when produced alone.

A platform is a hardware-cum-software capital installation that has multiple production capabilities

Exercises for Chapter 8

The relationship between output Q and the single variable input L is given by the form ![]() . Capital is fixed. This relationship is given in the table below for a range of L values.

. Capital is fixed. This relationship is given in the table below for a range of L values.

| L | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| Q | 5 | 7.07 | 8.66 | 10 | 11.18 | 12.25 | 13.23 | 14.14 | 15 | 15.81 | 16.58 | 17.32 |

Add a row to this table and compute the MP.

Draw the total product (TP) curve to scale, either on graph paper or in a spreadsheet.

Inspect your graph to see if it displays diminishing MP.

The TP for different output levels for Primitive Products is given in the table below.

| Q | 1 | 6 | 12 | 20 | 30 | 42 | 53 | 60 | 66 | 70 |

| L | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

Graph the TP curve to scale.

Add a row to the table and enter the values of the MP of labour. Graph this in a separate diagram.

Add a further row and compute the AP of labour. Add it to the graph containing the MP of labour.

By inspecting the AP and MP graph, can you tell if you have drawn the curves correctly? How?

A short-run relationship between output and total cost is given in the table below.

| Output | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| Total Cost | 12 | 27 | 40 | 51 | 61 | 70 | 80 | 91 | 104 | 120 |

What is the total fixed cost of production in this example?

Add four rows to the table and compute the TVC, AFC, AVC and ATC values for each level of output.

Add one more row and compute the MC of producing additional output levels.

Graph the MC and AC curves using the information you have developed.

Consider the long-run total cost structure for the two firms A and B below.

| Output | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Total cost A | 40 | 52 | 65 | 80 | 97 | 119 | 144 |

| Total cost B | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | 90 |

Compute the long-run ATC curve for each firm.

Plot these curves and examine the type of scale economies each firm experiences at different output levels.

Use the data in Exercise 8.4,

Calculate the long-run MC at each level of output for the two firms.

Verify in a graph that these LMC values are consistent with the LAC values.

Optional: Suppose you are told that a firm of interest has a long-run average total cost that is defined by the relationship LATC=4+48/q.

In a table, compute the LATC for output values ranging from

. Plot the resulting LATC curve.

. Plot the resulting LATC curve.What kind of returns to scale does this firm never experience?

By examining your graph, what will be the numerical value of the LATC as output becomes very large?

Can you guess what the form of the long-run MC curve is?