10: Monopoly

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 108292

Chapter 10: Monopoly

In this chapter we will explore:

| 10.1 | Why monopolies exist |

| 10.2 | How monopolists maximize profits |

| 10.3 | Long-run behaviour |

| 10.4 | Monopoly and market efficiency |

| 10.5 | Price discrimination |

| 10.6 | Cartels |

| 10.7 | Invention, innovation and rent seeking |

10.1 Monopolies

In analyzing perfect competition we emphasized the difference between the industry and the individual supplier. The individual supplier is an atomistic unit with no market power. In contrast, a monopolist has a great deal of market power, for the simple reason that a monopolist is the sole supplier of a particular product and so really is the industry. The word monopoly, comes from the Greek words monos, meaning one, and polein meaning to sell. When there is just a single seller, our analysis need not distinguish between the industry and the individual firm. They are the same on the supply side.

Furthermore, the distinction between long run and short run is blurred, because a monopoly that continues to survive as a monopoly obviously sees no entry or exit. This is not to say that monopolized sectors of the economy do not evolve, they do. Sometimes they die, sometimes they evolve in a different role. For example, when digital cameras entered the market place in the eighties the Polaroid Land camera (which printed film straight out of the camera) 'died' because the demand side of the market lost interest. The Blackberry 'smart' phone had a virtual monopoly on this product into the new millennium until Apple and Nokia entered the market.

A monopolist is the sole supplier of an industry's output, and therefore the industry and the firm are one and the same.

Monopolies can exist and exert their dominance in the market place for several reasons; scale economies, national policy, successful prevention of entry, research and development combined with patent protection.

Natural monopolies

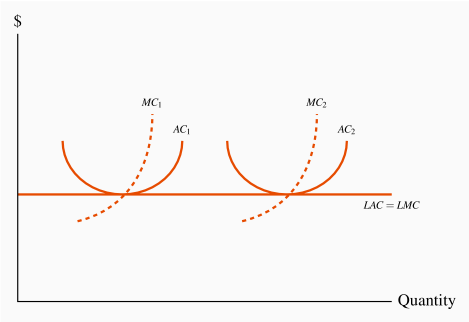

Traditionally, monopolies were viewed as being 'natural' in some sectors of the economy. This means that scale economies define some industries' production and cost structures up to very high output levels, and that the whole market might be supplied at least cost by a single firm.

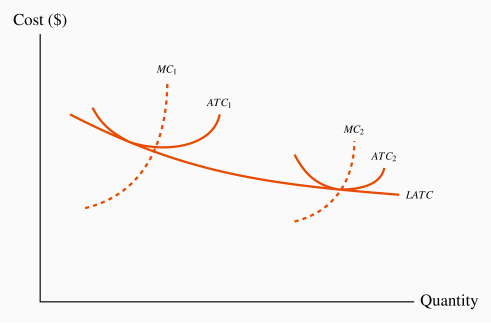

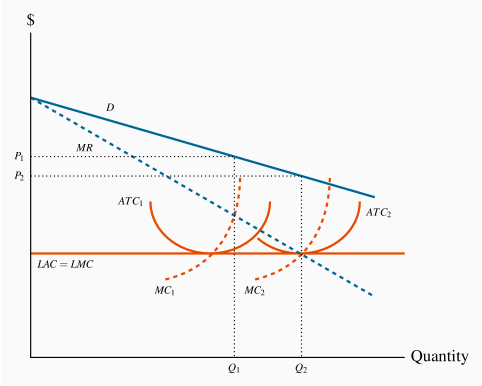

Consider the situation depicted in Figure 10.1. The

long-run ATC curve declines indefinitely. There is no output level where

average costs begin to increase. Imagine now having several firms, each

producing with a plant size corresponding to the short-run average cost

curve ![]() , or alternatively a single larger firm using a plant size

denoted by

, or alternatively a single larger firm using a plant size

denoted by ![]() . The small firms in this case cannot compete with the

larger firm because the larger firm has lower production costs and can

undercut the smaller firms, and supply the complete market in the

process. Such a scenario is termed a natural monopoly.

. The small firms in this case cannot compete with the

larger firm because the larger firm has lower production costs and can

undercut the smaller firms, and supply the complete market in the

process. Such a scenario is termed a natural monopoly.

Natural monopoly: one where the ATC of producing any output declines with the scale of operation.

Electricity distribution in some of Canada's provinces is in the hands of a single supplier – Hydro Quebec or Hydro One in Ontario, for example. These distributors are natural monopolies in the sense described above: Unit distribution costs decline with size. In contrast, electricity production is not 'naturally' a monopoly. Other suppliers were once thought of as 'natural' monopolies also, but are no longer. Bell Canada was considered to be a natural monopoly in the era of land lines: It would not make economic sense to run several sets of phone lines to every residence. But that was before the arrival of cell phones, broadband and satellites. Canada Post was also thought to be a natural monopoly, until the advent of FEDEX, UPS and other couriers proved otherwise. Invention can compete away a 'natural' monopoly.

In reality there are very few pure monopolies. Facebook, Microsoft, Amazon, Apple, Netflix and Google may be extraordinarily dominant in their markets, but they are not the only suppliers of the services or products that they offer. There exist other products that are similar.

National and Provincial Policy

Government policy can foster monopolies. Some governments are, or once were, proud to have a 'national carrier' in the airline industry – Air Canada in Canada or British Airways in the UK. The mail service was viewed as a symbol of nationhood in Canada and the US: Canada Post and the US Postal system are national emblems that have historic significance. They were vehicles for integrating the provinces or states at various points in the federal lives of these countries.

In the modern era, most of Canada's provinces have decided to create a provincial monopoly crown corporation for the sale of cannabis. But competition abounds in the form of an illegal market.

The down side of such nationalist policies is that they can be costly to the taxpayer. Industries that are not subject to competition can become fat and uncompetitive: Managers have insufficient incentives to curtail costs; unions realize the government is committed to sustain the monopoly and push for higher wages than under a more competitive structure, and innovation may be less likely to occur.

Maintaining barriers to entry

Monopolies can continue to survive if they are successful in preventing the entry of new firms and products. Patents and copyrights are one vehicle for preserving the sole-supplier role, and are certainly necessary to encourage firms to undertake the research and development (R&D) for new products.

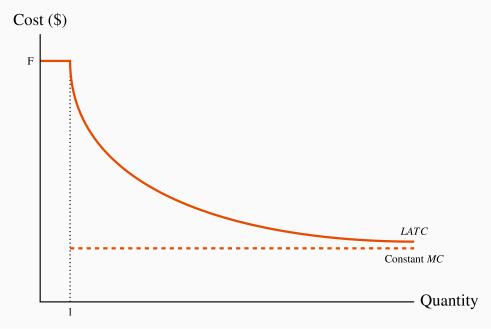

Many corporations produce products that require a large up-front investment; this might be in the form of research and development, or the construction of costly production facilities. For example, Boeing or Airbus incurs billions of dollars in developing new aircraft; pharmaceuticals may have to invest a billion dollars to develop a new drug. However, once such an investment is complete, the cost of producing each unit of output may be relatively low. This is particularly true in pharmaceuticals. Such a phenomenon is displayed in Figure 10.2. In this case the average cost for a small number of units produced is high, but once the fixed cost is spread over an ever larger output, the average cost declines rapidly, and in the limit approaches the marginal cost. These production structures are common in today's global economy, and they give rise to markets characterized either by a single supplier or a small number of suppliers.

This figure is useful in understanding the role of patents. Suppose that Pharma A spends one billion dollars in developing a new drug and has constant unit production costs thereafter, while Pharma B avoids research and development and simply imitates Pharma A's product. Clearly Pharma B would have a LATC equal to its LMC, and would be able to undercut the initial developer of the drug. Such an outcome would discourage investment in new products and the economy at large would suffer as a consequence. Economies would be worse off if protection is not provided to the developers of new products because, if such protection is not offered, potential developers will not have the incentive to incur the up-front investment required.

While copyright and patent protection is legal, predatory pricing is an illegal form of entry barrier, and we explore it more fully in Chapter 14. An example would be where an existing firm that sells nationally may deliberately undercut the price of a small local entrant to the industry. Airlines with a national scope are frequently accused of posting low fares on flights in regional markets that a new carrier is trying to enter.

Political lobbying is another means of maintaining monopolistic power. For example, the Canadian Wheat Board had fought successfully for decades to prevent independent farmers from marketing wheat. This Board lost its monopoly status in August 2012, when the government of the day decided it was not beneficial to consumers or farmers in general. Numerous 'supply management' policies are in operation all across Canada. Agriculture is protected by production quotas. All maple syrup in Quebec must be marketed through a single monopoly supplier.

Critical networks also form a type of barrier, though not always a monopoly. Microsoft's Office package has an almost monopoly status in word processing and spreadsheet analysis for the reason that so many individuals and corporations use it. The fact that we know a business colleague will be able to edit our documents if written in Word, provides us with an incentive to use Word, even if we might prefer Wordperfect as a vehicle for composing documents. We develop the concept of strategic entry prevention further in Chapter 11.

10.2 Profit maximizing behaviour

We established in the previous chapter that, in deciding upon a profit-maximizing output, any firm should produce up to the point where the additional cost equals the additional revenue from a unit of output. What distinguishes the supply decision for a monopolist from the supply decision of the perfect competitor is that the monopolist faces a downward sloping demand. A monopolist is the sole supplier and therefore must meet the full market demand. This means that if more output is produced, the price must fall. We will illustrate the choice of a profit maximizing output using first a marginal-cost/marginal-revenue approach; then a supply/demand approach.

Marginal revenue and marginal cost

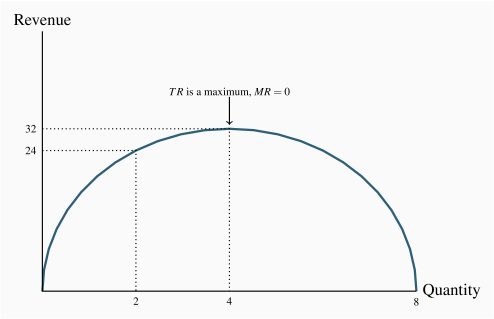

Table 10.1 displays price and quantity values for a demand curve in columns 1 and 2. Column 3 contains the sales revenue generated at each output. It is the product of price and quantity. Since the price denotes the revenue per unit, it is sometimes referred to as average revenue. The total revenue (TR) reaches a maximum at $32, where 4 units of output are produced. A greater output necessitates a lower price on every unit sold, and in this case revenue falls if the fifth unit is brought to the market. Even though the fifth unit sells for a positive price, the price on the other 4 units is now lower and the net effect is to reduce total revenue. This pattern reflects what we examined in Chapter 4: As price is lowered from the highest possible value of $14 (where 1 unit is demanded) and the corresponding quantity increases, revenue rises, peaks, and ultimately falls as output increases. In Chapter 4 we explained that this maximum revenue point occurs where the price elasticity is unity (-1), at the midpoint of a linear demand curve.

| Quantity | Price | Total | Marginal | Marginal | Total | Profit |

| (Q) | (P) | revenue (TR) | revenue (MR) | cost (MC) | cost (TC) | |

| 0 | 16 | |||||

| 1 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 2 | 2 | 12 |

| 2 | 12 | 24 | 10 | 3 | 5 | 19 |

| 3 | 10 | 30 | 6 | 4 | 9 | 21 |

| 4 | 8 | 32 | 2 | 5 | 14 | 18 |

| 5 | 6 | 30 | -2 | 6 | 20 | 10 |

| 6 | 4 | 24 | -6 | 7 | 27 | -3 |

| 7 | 2 | 14 | -10 | 8 | 35 | -21 |

Related to the total revenue function is the marginal revenue function. It is the addition to total revenue due to the sale of one more unit of the commodity.

Marginal revenue is the change in total revenue due to selling one more unit of the good.

Average revenue is the price per unit sold.

The MR in this example is defined in the fourth column of Table 10.1. When the quantity sold increases from 1 unit to 2 units total revenue increases from $14 to $24. Therefore the marginal revenue associated with the second unit of output is $10. When a third unit is sold TR increases to $30 and therefore the MR of the third unit is $6. As output increases the MR declines and eventually becomes negative – at the point where the TR is a maximum: If TR begins to decline then the additional revenue is by definition negative.

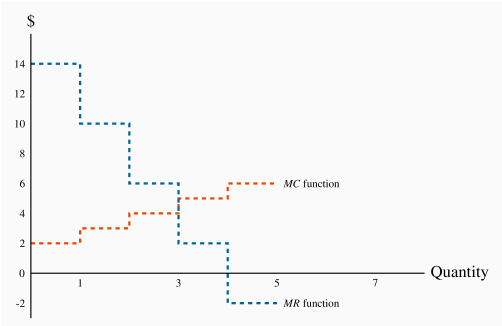

The MR function is plotted in Figure 10.4. It becomes negative when output increases from 4 to 5 units.

The optimal output

This producer has a marginal cost structure given in the fifth column of the table, and this too is plotted in Figure 10.4. Our profit maximizing rule from Chapter 8 states that it is optimal to produce a greater output as long as the additional revenue exceeds the additional cost of production on the next unit of output. In perfectly competitive markets the additional revenue is given by the fixed price for the individual producer, whereas for the monopolist the additional revenue is the marginal revenue. Consequently as long as MR exceeds MC for the next unit a greater output is profitable, but once MC exceeds MR the production of additional units should cease.

From Table 10.1 and Figure 10.4 it is clear that the optimal output is at 3 units. The third unit itself yields a profit of 2$, the difference between MR ($6) and MC ($4). A fourth unit however would reduce profit by $3, because the MR ($2) is less than the MC ($5). What price should the producer charge? The price, as always, is given by the demand function. At a quantity sold of 3 units, the corresponding price is $10, yielding total revenue of $30.

Profit is the difference between total revenue and total cost. In Chapter 8

we computed total cost as the average cost times the

number of units produced. It can also be computed as the sum of costs

associated with each unit produced: The first unit costs $2, the second $3

and the third $4. The total cost of producing 3 units is the sum of these

dollar values: ![]() . The profit-maximizing output therefore

yields a profit of $21 (

. The profit-maximizing output therefore

yields a profit of $21 (![]() ).

).

Supply and demand

When illustrating market behaviour it is convenient to describe behaviour by simple linear supply and demand functions that are continuous, rather than the 'step' functions used in the preceding example. As explained in Chapter 5, in using continuous curves to represent a market we implicitly assume that a unit of output can be broken into subunits. In the example above we assumed that sales always involve one whole unit of the product being sold. In fact many goods can be sold in fractional units: Gasoline can be sold in fractions of a litre; fruits and vegetables can be sold in fractions of a kilogram, and so forth. Table 10.2 below furnishes the data for our analysis.

| Price | Quantity | Total | Total | Profit |

| demanded | revenue | cost | ||

| 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 11 | 2 | 22 | 1 | 21 |

| 10 | 4 | 40 | 4 | 36 |

| 9 | 6 | 54 | 9 | 45 |

| 8 | 8 | 64 | 16 | 48 |

| 7 | 10 | 70 | 25 | 45 |

| 6 | 12 | 72 | 36 | 36 |

| 5 | 14 | 70 | 49 | 21 |

| 4 | 16 | 64 | 64 | 0 |

| 3 | 18 | 54 | 81 | -27 |

| 2 | 20 | 40 | 100 | -60 |

| 1 | 22 | 22 | 121 | -99 |

| 0 | 24 | 0 | 144 | -144 |

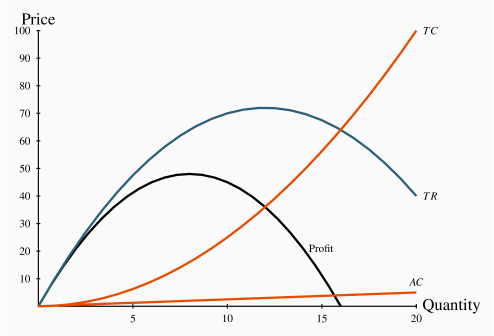

The first two columns define the demand curve. Total revenue is the product of price and quantity and given in column 3. The cost data are given in column 4, and profit – the difference between total revenue and total cost is in the final column. Profit is maximized where the difference between revenue and cost is greatest; in this case where the output is 8 units. At lower or higher outputs profit is less. Figure 10.5 contains the curves defining total revenue (TR), total cost (TC) and profit. These functions can be obtained by mapping all of the revenue-quantity combinations, the cost-quantity combinations, and the profit-quantity combinations as a series of points, and joining these points to form the smooth functions displayed. The vertical axis is measured in dollars, the horizontal axis in units of output. Graphically, profit is maximized where the dollar difference between TR and TC is greatest; that is at the output where the vertical distance between the two curves is greatest. This difference, which is also defined by the profit curve, occurs at a value of 8 units, corresponding to the outcome in Table 10.2.

At any quantity less than this output, profit would rise with additional output. This is because, from a less-than-optimal output, the additional revenue from increased sales exceeds the increased cost associated with producing those units: Stated differently, the marginal revenue would exceed the marginal cost. Conversely, outputs greater than the optimum result in a MR less than the associated MC. Accordingly, since outputs where MR>MC are too low, and outputs where MR<MC are too high, the optimum must be where the MR=MC. Hence, the equality between MR and MC is implied in this diagram at the output where the difference between TR and TC is greatest.

Note finally that total revenue is maximized where the TR curve reaches a peak. In this example that occurs at a value of 12 units of output. This is to be anticipated, as we learned in Chapter 4, because the midpoint of the demand schedule in Table 10.2 occurs at that value.

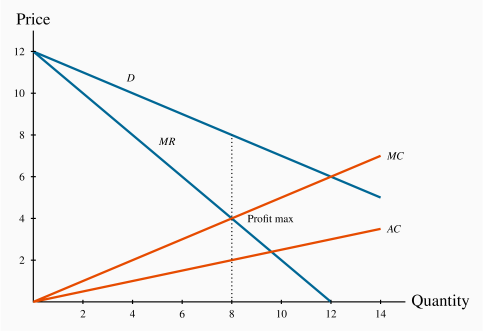

Figure 10.6 displays the demand curve for the market, the MR curve, and the monopolist's MC and AC curves. Consider first the marginal revenue curve. In contrast to the previous example, where only whole or integer units could be sold, in this example units can be sold in fractional amounts, and the MR curve must reflect this. To determine the position of the MR curve, note that with a straight-line demand curve total revenue is a maximum at the midpoint of the demand curve. Any increase in output results in reduced revenue: Stated differently, the marginal revenue becomes negative at that output. Up to that output the MR is positive, as illustrated in Figure 10.3. Accordingly, the MR curve must intersect the quantity axis midway between zero and the horizontal-axis intercept of the demand curve. Geometrically, since the MR intersects the quantity axis half way to the horizontal intercept of the demand curve, it must have a slope that is twice the slope of the demand curve.

By observing the data in columns 1 and 2 of the table, the demand curve

intercepts are ![]() , and from above discussion the MR curve

has intercepts

, and from above discussion the MR curve

has intercepts ![]() . The AC is obtained by dividing TC by

output in Table 10.2, and the MC can be also

calculated as the change in total cost divided by the change in output

from Table 10.2. The result of these calculations

is displayed in Figure 10.6.

. The AC is obtained by dividing TC by

output in Table 10.2, and the MC can be also

calculated as the change in total cost divided by the change in output

from Table 10.2. The result of these calculations

is displayed in Figure 10.6.

The profit maximizing output is 8 units, where MC=MR. The price at which 8 units can be sold is read from the demand curve1, or the first column in Table 10.2. It is $8. And, as expected, this price-quantity combination maximizes profit. Table 10.2 indicates that profit is maximized at $48, at q=8.

Demand elasticity and marginal revenue

We have shown above that the MR curve cuts the horizontal axis at a quantity where the elasticity of demand is unity. We know from Chapter 4 that demand is elastic at points on the demand curve above this unit-elastic point. Furthermore, since the intersection of MR and MC must be at a positive dollar value (MC cannot be negative), then it must be the case that the profit maximizing price for a monopolist always lies on the elastic segment of the demand curve.

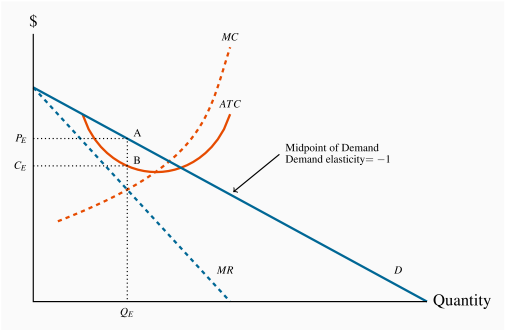

A general graphical representation

In Figure 10.7 we generalize the graphical representation of

the monopoly profit maximizing output by allowing the MC and ATC curves

to be nonlinear. The optimal output is at ![]() , where MR=MC, and the

price

, where MR=MC, and the

price ![]() sustains that output. With the average cost known, profit per

unit is AB, and therefore total profit is this margin multiplied by the

number of units sold,

sustains that output. With the average cost known, profit per

unit is AB, and therefore total profit is this margin multiplied by the

number of units sold, ![]() .

.

Total profit is therefore ![]()

Note that the monopolist may not always make a profit. Losses could result in Figure 10.7 if average costs were to rise so that the ATC were everywhere above the demand curve, or if the demand curve shifted down to being everywhere below the ATC curve. In the longer term the monopolist would have to either reduce costs or perhaps stimulate demand through advertising if she wanted to continue in operation.

10.3 Long-run choices

Consider next the impact of a shift in demand upon the profit maximizing choice of this firm. A rightward shift in demand in Figure 10.7 also yields a new MR curve. The firm therefore chooses a new level of output, using the same profit maximizing rule: Set MC=MR. This output will be greater than the previous output, but again the price must be on an elastic portion of the new demand curve. If operating with the same plant size, the MC and ATC curves do not change and the new profit per unit is again read from the ATC curve.

By this stage the curious student will have asked: "What happens to plant size in the long run?" For example, is the monopolist in Figure 10.7 using the most appropriate plant size in the first place? Even if she is, should the monopolist consider adopting an expanded plant size in response to the shift in demand?

The answer is: In the long run the monopolist is free to choose whatever plant size is best. Her initial plant size might have been optimal for the demand she faced, but if it was, it is unlikely to be optimal for the larger scale of production associated with the demand shift. Accordingly, with the new demand curve, she must consider how much profit she could make using different plant sizes.

To illustrate one possibility, we will think of this firm as having constant returns to scale at all output ranges, as displayed in Figure 10.8. (Our reasoning carries through if the LAC slopes downwards; the graph just becomes a little more complex.) The key characteristic of constant returns to scale is that a doubling of inputs leads to a doubling of output. Therefore, if the per-unit cost of inputs is fixed, a doubling of inputs (and therefore output) leads exactly to a doubling of costs. This implies that, when the firm varies its plant size and its labour use, the cost of producing each additional unit must be constant. The long-run marginal cost LMC is therefore constant and equals the ATC in the long run.

Figure 10.9 describes the market for this good. The optimal output and price are determined in the usual manner: Set MC=MR. If the monopolist has plant size corresponding to ATC1, the optimal output is Q1 and should be sold at the price P1.The key issue now is: Given the demand conditions, could the monopolist make more profit by choosing a plant size that differs from the one corresponding to ATC1?

In this instance the answer is a clear 'yes'. Her LMC curve is horizontal and so, by increasing output from Q1 to Q2 she earns a profit on each additional unit in that range, because the MR curve lies above the LMC curve. In order to produce the output level Q2 at least cost she must choose a plant size corresponding to AC2.

10.4 Output inefficiency

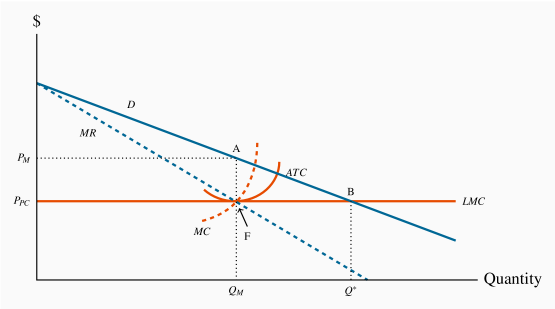

A characteristic of perfect competition is that it secures an efficient allocation of resources when there are no externalities in the market: Resources are used up to the point where their marginal cost equals their marginal value – as measured by the price that consumers are willing to pay. But a monopoly structure does not yield this output. Consider Figure 10.10.

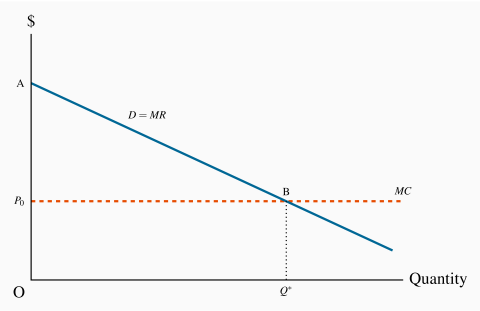

The monopolist's profit-maximizing output ![]() is where MC equals MR.

This output is inefficient for the reason that we developed in Chapter 5:

If output is increased beyond

is where MC equals MR.

This output is inefficient for the reason that we developed in Chapter 5:

If output is increased beyond ![]() the additional benefit

exceeds the additional cost of producing it. The additional benefit is

measured by the willingness of buyers to pay – the market demand curve. The

additional cost is the long-run MC curve under the assumption of constant

returns to scale. Using the terminology from Chapter 5,

there is a deadweight loss equal to the area ABF. This is termed

allocative inefficiency.

the additional benefit

exceeds the additional cost of producing it. The additional benefit is

measured by the willingness of buyers to pay – the market demand curve. The

additional cost is the long-run MC curve under the assumption of constant

returns to scale. Using the terminology from Chapter 5,

there is a deadweight loss equal to the area ABF. This is termed

allocative inefficiency.

Allocative inefficiency arises when resources are not appropriately allocated and result in deadweight losses .

Perfect competition versus monopoly

The area ABF can also be considered as the efficiency loss associated with

having a monopoly rather than a perfectly competitive market structure. In

perfect competition the supply curve is horizontal. This is achieved by

having firms enter and exit when more or less must be produced. Accordingly,

if the perfectly competitive industry's supply curve approximates

the monopolist's long-run marginal cost curve2, we can say that if the monopoly were turned into a

competitive industry, output would increase from ![]() to

to ![]() . The

deadweight loss is one measure of the superiority of the perfectly

competitive structure over the monopoly structure.

. The

deadweight loss is one measure of the superiority of the perfectly

competitive structure over the monopoly structure.

Note that this critique of monopoly is not initially focused upon profit. While monopoly profits are what frequently irk the public, we have focused upon resource allocation inefficiencies. But in a real sense the two are related: Monopoly inefficiencies arise through output being restricted, and it is this output reduction – achieved by maintaining a higher than competitive price – that gives rise to those profits. Nonetheless, there is more than just a shift in purchasing power from the buyer to the seller. Deadweight losses arise because output is at a level lower than the point where the MC equals the value placed on the good; thus the economy is sacrificing the possibility of creating additional surplus.

Given that monopoly has this undesirable inefficiency, what measures should be taken, if any, to counter the inefficiency? We will see what Canada's Competition Act has to say in Chapter 14 and also examine what other measures are available to control monopolies.

10.5 Price discrimination

A common characteristic in the pricing of many goods is that different individuals pay different prices for goods or services that are essentially the same. Examples abound: Seniors get a reduced rate for coffee in Burger King; hair salons charge women more than they charge men; bank charges are frequently waived for juniors. Price discrimination involves charging different prices to different consumers in order to increase profit.

Price discrimination involves charging different prices to different consumers in order to increase profit.

A strict definition of discrimination involves different prices for identical products. We all know of a school friend who has been willing to take the midnight flight to make it home at school break at a price he can afford. In contrast, the business executive prefers the seven a.m. flight to arrive for a nine a.m. business meeting in the same city at several times the price. These are very mild forms of price discrimination, since a midnight flight (or a midday flight) is not a perfect substitute for an early morning flight. Price discrimination is practiced because buyers are willing to pay different amounts for a good or service, and the supplier may have a means of profiting from this. Consider the following example.

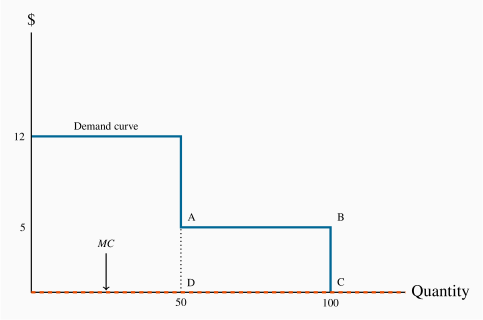

Family Flicks is the local movie theatre. It has two distinct groups of customers – those of prime age form one group; youth and seniors form the other. Family Flicks has done its market research and determined that each group accounts for 50 percent of the total market of 100 potential viewers per screening. It has also established that the prime-age group members are willing to pay $12 to see a movie, while the seniors and youth are willing to pay just $5. How should the tickets be priced?

Family Flicks has no variable costs, only fixed costs. It must pay a $100 royalty to the movie maker each time it shows the current movie, and must pay a cashier and usher $20 each. Total costs are therefore $140, regardless of how many people show up – short-run MC is zero. On the pricing front, as illustrated in Table 10.3 below, if Family Flicks charges $12 per ticket it will attract 50 viewers, generate $600 in revenue and therefore make a profit of $460.

| P=$5 | P=$12 | Twin price | |

| No. of customers | 100 | 50 | |

| Total revenue | $500 | $600 | $850 |

| Total costs | $140 | $140 | $140 |

| Profit | $360 | $460 | $710 |

In contrast, if it charges $5 it can fill the theatre, because each of the

prime-age individuals is willing to pay more than $5, but the seniors and

youth are now offered a price they too are willing to pay. However, the

total revenue is now only $500 (![]() ), and profits are

reduced to $360. It therefore decides to charge the high price and leave

the theatre half-empty, because this strategy maximizes its profit.

), and profits are

reduced to $360. It therefore decides to charge the high price and leave

the theatre half-empty, because this strategy maximizes its profit.

Suppose finally that the theatre is able to segregate its customers. It can ask the young and senior customers for identification upon entry, and in this way charge them a lower price, while still maintaining the higher price to the prime-age customers. If it can execute such a plan Family Flicks can now generate $850 in revenue – $600 from the prime-age group and $250 from the youth and seniors groups. Profit soars to $710.

There are two important conditions for this scheme to work:

The seller must be able to segregate the market at a reasonable cost. In the movie case this is achieved by asking for identification.

The second condition is that resale must be impossible or impractical. For example, we rule out the opportunity for young buyers to resell their tickets to the prime-age individuals. Sellers have many ways of achieving this – they can require immediate entry to the movie theatre upon ticket purchase, they can stamp the customer's hand, they can demand the showing of ID with the ticket when entering the theatre area.

Frequently we think of sellers who offer price reductions to specific groups as being generous. For example, hotels may levy only a nominal fee for the presence of a child, once the parents have paid a suitable rate for the room or suite in which a family stays. The hotel knows that if it charges too much for the child, it may lose the whole family as a paying unit. The coffee shop offering cheap coffee to seniors is interested in getting a price that will cover its variable cost and so contribute to its profit. It is unlikely to be motivated by philanthropy, or to be concerned with the financial circumstances of seniors.

Price discrimination has a further interesting feature that is illustrated in Figure 10.11: It frequently reduces the deadweight loss associated with a monopoly seller!

In our Family Flicks example, the profit maximizing monopolist that did not, or could not, price discriminate left 50 customers unsupplied who were willing to pay $5 for a good that had a zero MC. This is a deadweight loss of $250 because 50 seniors and youth valued a commodity at $5 that had a zero MC. Their demand was not met because, in the absence of an ability to discriminate between consumer groups, Family Flicks made more profit by satisfying the demand of the prime-age group alone. But in this example, by segregating its customers, the firm's profit maximization behaviour resulted in the DWL being eliminated, because it supplied the product to those additional 50 individuals. In this instance price discrimination improves welfare, because more of a good is supplied in a situation where market valuation exceeds marginal cost.

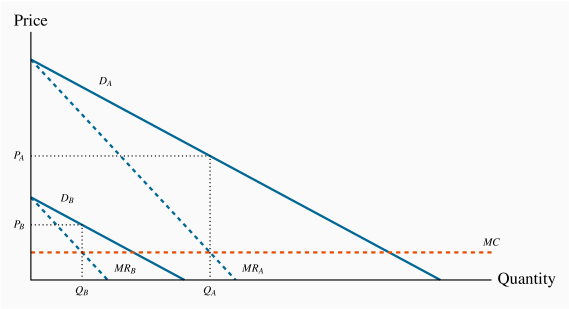

In the preceding example we simplified the demand side of the market by assuming that every individual in a given group was willing to pay the same price – either $12 or $5. More realistically each group can be defined by a downward-sloping demand curve, reflecting the variety of prices that buyers in a given market segment are willing to pay. It is valuable to extend the analysis to include this reality. For example, a supplier may face different demands from her domestic and foreign buyers, and if she can segment these markets she can price discriminate effectively.

Consider Figure 10.12 where two segmented demands are displayed, DA and DB, with their associated marginal revenue curves, MRA and MRB. We will assume that marginal costs are constant for the moment. It should be clear by this point that the profit maximizing solution for the monopoly supplier is to supply an amount to each market where the MC equals the MR in each market: Since the buyers in one market cannot resell to buyers in the other, the monopolist considers these as two different markets and therefore maximizes profit by applying the standard rule. She will maximize profit in market A by supplying the quantity QA and in market B by supplying QB. The prices at which these quantities can be sold are PA and PB. These prices, unsurprisingly, are different – the objective of segmenting markets is to increase profit by treating the markets as distinct.

An example of this type of price discrimination is where pharmaceutical companies sell drugs to less developed economies at a lower price than to developed economies. The low price is sufficient to cover marginal cost and is therefore profitable - provided the high price market covers the fixed costs.

The preceding examples involved two separable groups of customers and are very real. This kind of group segregation is sometimes called third degree price discrimination. But it may be possible to segregate customers into several groups rather than just two. In the limit, if we could charge a different price to every consumer in a market, or for every unit sold, the revenue accruing to the monopolist would be the area under the demand curve up to the output sold. Though primarily of theoretical interest, this is illustrated in Figure 10.13. It is termed perfect price discrimination, and sometimes first degree price discrimination. Such discrimination is not so unrealistic: A tax accountant may charge different customers a different price for providing the same service; home renovators may try to charge as much as any client appears willing to pay.

Second degree price discrimination is based on a different concept of buyer identifiability. In the cases we have developed above, the seller is able to distinguish the buyers by observing a vital characteristic that signals their type. It is also possible that, while individuals might have defining traits which influence their demands, such traits might not be detectable by the supplier. Nonetheless, it is frequently possible for the supplier to offer different pricing options (corresponding to different uses of a product) that buyers would choose from, with the result that her profit would be greater than under a uniform price with no variation in the use of the service. Different cell phone 'plans', or different internet plans that users can choose from are examples of this second-degree discrimination.

10.6 Cartels: Acting like a monopolist

A cartel is a group of suppliers that colludes to operate like a monopolist. The cartel formed by the members of the Organization of Oil Exporting Countries (OPEC) is an example of a cartel that was successful in achieving its objectives for a long period. This cartel first flexed its muscles in 1973, by increasing the world price of oil from $3 per barrel to $10 per barrel. The result was to transfer billions of dollars from the energy-importing nations in Europe and North America to OPEC members – the demand for oil is relatively inelastic, hence an increase in price increases total expenditures.

A cartel is a group of suppliers that colludes to operate like a monopolist.

A second renowned cartel is managed by De Beers, which controls a large part of the world's diamond supply. In Canada, agricultural marketing boards are a means of restricting supply legally. Such cartels may have thousands of members. By limiting entry, through requiring a production 'quota', the incumbents can charge a higher price than if entry to the industry were free.

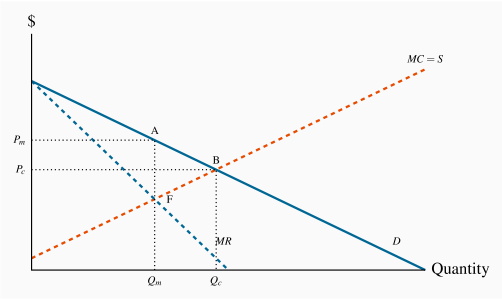

To illustrate the dynamics of cartels consider Figure 10.14. Several producers, with given production capacities,

come together and agree to restrict output with a view to increasing price

and therefore profit. This may be done with the agreement of the government,

or it may be done secretively, and possibly against the law. Each firm has a

MC curve, and the industry supply is defined as the sum of these marginal

cost curves, as illustrated in Figure 9.3. The

resulting cartel is effectively one in which there is a single supplier with

many different plants – a multi-plant monopolist. To maximize profits this

organization will choose an output level ![]() where the MR equals the MC. In contrast, if these firms act competitively the output chosen will be

where the MR equals the MC. In contrast, if these firms act competitively the output chosen will be

![]() . The competitive output yields no supernormal profit, whereas the

monopoly/cartel output does.

. The competitive output yields no supernormal profit, whereas the

monopoly/cartel output does.

The cartel results in a deadweight loss equal to the area ABF, just as in the standard monopoly model.

Cartel instability

Some cartels are unstable in the long run. In the first instance, the degree of instability depends on the authority

that the governing body of the cartel can exercise over its members, and

upon the degree of information it has on the operations of its members. If a

cartel is simply an arrangement among producers to limit output, each

individual member of the cartel has an incentive to increase its output,

because the monopoly price that the cartel attempts to sustain exceeds the

cost of producing a marginal unit of output. In Figure 10.14 each firm has a MC of output equal to $F when the

group collectively produces the output ![]() . Yet any firm that brings

output to market, beyond its agreed production limit, at the price

. Yet any firm that brings

output to market, beyond its agreed production limit, at the price ![]() will make a profit of AF on that additional output – provided the other members of the cartel agree to restrict their output.

Since each firm faces the same incentive to increase output, it is difficult

to restrain all members from doing so.

will make a profit of AF on that additional output – provided the other members of the cartel agree to restrict their output.

Since each firm faces the same incentive to increase output, it is difficult

to restrain all members from doing so.

Individual members are more likely to abide by the cartel rules if the organization can sanction them for breaking the supply-restriction agreement. Alternatively, if the actions of individual members are not observable by the organization, then the incentive to break ranks may be too strong for the cartel to sustain its monopoly power.

We will see in Chapter 14 that Canada's Competition Act forbids the formation of cartels, as it forbids many other anti-competitive practices. At the same time, our governments frequently are the driving force in the formation of domestic cartels.

In the second instance, cartels may be undermined eventually by the emergence of new products and new technologies. OPEC has lost much of its power in the modern era because of technological developments in oil recovery. Canada's 'tar sands' yield oil, as a result of technological developments that enabled producers to separate the oil from the earth it is mixed with. Fracking technologies are another means of extracting oil that is discovered in small pockets and encased in rock. The supply coming from these new technologies has limited the ability of the old OPEC cartel to increase prices through supply restriction.

The new sharing economy has brought competition to some traditional cartels. City taxis are an example of such a formation: Traditionally, entry has been restricted to drivers who hold a permit (medallion), and fares are higher as a consequence of the resulting reduced supply. A secondary market then develops for these medallions, in which the city may offer new medallions through auction, or existing owners may exit and sell their medallions. Restricted entry has characterized most of Canada's major cities. Depending on the strictness of the entry process, medallions are worth correspondingly more. By 2012, medallions were selling in New York and Boston for a price in the neighborhood of one million dollars.

But ride-sharing start-up companies changed all of that. As Western examples, Uber and Lyft developed smart-phone apps that link demanders for rides with drivers, who may, or may not be, part of the traditional taxi companies. Such start-ups have succeeded in taking a significant part of the taxi business away from the traditional operators. As a result, the price of taxi medallions on the open market has plunged. From trading in the range of $1m. in New York in 2012, medallions are being offered in 2019 at about one fifth of that price. In Toronto, some medallions were traded in the range of $300,000 in 2012, but are on offer in 2019 for prices in the range of $30,000.

Not surprisingly, the traditional taxi companies charge that ride-hailing operators are violating the accepted rules governing the taxi business, and have launched legal suits against them and against local governments, and lobbied governments to keep them out of their cities.

In the new 'sharing economy', of which ride hailing companies are an example, participants operate with less traditional capital, and the communications revolution has been critical to their success. Home owners can use an online site to rent a spare bedroom in their house to visitors to their city (Airbnb), and thus compete with hotels. The main capital in this business is in the form of the information technology that links potential buyers to potential sellers.

Information on medallion prices in Canada can be found by, for example, searching at http://www.kijiji.ca

10.7 Invention, innovation and rent seeking

Invention and innovation are critical aspects of the modern economy. In some sectors of the economy, firms that cannot invent or innovate are liable to die. Invention is a genuine discovery, whereas innovation is the introduction of a new product or process.

Invention is the discovery of a new product or process through research.

Product innovation refers to new or better goods or services.

Process innovation refers to new or better production or supply.

To this point we have said little that is good about monopolies. However, the economist Joseph Schumpeter argued that, while monopoly leads to resource misallocation in the economy, this cost might be offset by the greater tendency for monopoly firms to invent and innovate. This is because such firms have more profit and therefore more resources with which to fund R&D and may therefore be more innovative than competitive firms. If this were true then, taking a long-run dynamic view of the marketplace, monopolies could have lower costs and more advanced products than competitive firms and thus benefit the consumer.

While this argument has some logical appeal, it falls short on several counts. First, even if large firms carry out more research than competitive firms, there is no guarantee that the ensuing benefits carry over to the consumer. Second, the results of such research may be used to prevent entry into the industry in question. Firms may register their inventions and gain use protection before a competitor can come up with the same or a similar invention. Apple and Samsung each own tens of thousands of patents. Third, the empirical evidence on the location of most R&D is inconclusive: A sector with several large firms, rather than one with a single or very many firms, may be best. For example, if Apple did not have Samsung as a competitor, or vice versa, would the pace of innovation be as strong?

Fourth, much research has a 'public good' aspect to it. Research carried out at universities and government-funded laboratories is sometimes referred to as basic research: It explores the principles underlying chemistry, social relations, engineering forces, microbiology, etc., and has multiple applications in the commercial world. If disseminated, this research is like a public good – its fruits can be used in many different applications, and its use in one area does not preclude its use in others. Consequently, rather than protecting monopolies on the promise of more R&D, a superior government policy might be to invest directly in research and make the fruits of the research publicly available.

Modern economies have patent laws, which grant inventors a legal monopoly on use for a fixed period of time – perhaps fifteen years. By preventing imitation, patent laws raise the incentive to conduct R&D but do not establish a monopoly in the long run. Over the life of a patent the inventor charges a higher price than would exist if his invention were not protected; this both yields greater profits and provides the research incentive. When the patent expires, competition from other producers leads to higher output and lower prices for the product. Generic drugs are a good example of this phenomenon.

Patent laws grant inventors a legal monopoly on use for a fixed period of time.

The power of globalization once again is very relevant in patents. Not all countries have patent laws that are as strong as those in North America and Europe. The BRIC economies (Brazil, Russia, India and China) form an emerging power block. But their legal systems and enforcement systems are less well-developed than in Europe or North America. The absence of a strong and transparent legal structure inhibits research and development, because their fruits may be appropriated by competitors.

Rent seeking

Citizens are frequently appalled when they read of lobbying activities in their nation's capital. Every capital city in the world has an army of lobbyists, seeking to influence legislators and regulators. Such individuals are in the business of rent seeking, whose goal is to direct profit to particular groups, and protect that profit from the forces of competition. In Virginia and Kentucky we find that state taxes on cigarettes are the lowest in the US – because the tobacco leaf is grown in these states, and the tobacco industry makes major contributions to the campaigns of some political representatives.

Rent-seeking carries a resource cost: Imagine that we could outlaw the lobbying business and put these lobbyists to work producing goods and services in the economy instead. Their purpose is to maintain as much quasi-monopoly power in the hands of their clients as possible, and to ensure that the fruits of this effort go to those same clients. If this practice could be curtailed then the time and resources involved could be redirected to other productive ends.

Rent seeking is an activity that uses productive resources to redistribute rather than create output and value.

Industries in which rent seeking is most prevalent tend to be those in which the potential for economic profits is greatest – monopolies or near-monopolies. These, therefore, are the industries that allocate resources to the preservation of their protected status. We do not observe laundromat owners or shoe-repair businesses lobbying in Ottawa.

Conclusion

We have now examined two extreme types of market structure – perfect competition and monopoly. While many sectors of the economy operate in a way that is close to the competitive paradigm, very few are pure monopolies in that they have no close substitute products. Even firms like Microsoft, or De Beers, that supply a huge percentage of the world market for their product would deny that they are monopolies and would argue that they are subject to strong competitive pressures from smaller or 'fringe' producers. As a result we must look upon the monopoly paradigm as a useful way of analyzing markets, rather than being an exact description of the world. Accordingly, our next task is to examine how sectors with a few, several or multiple suppliers act when pursuing the objective of profit maximization. Many different market structures define the real economy, and we will concentrate on a limited number of the more important structures in the next chapter.

Key Terms

Monopolist: is the sole supplier of an industry's output, and therefore the industry and the firm are one and the same.

Natural monopoly: one where the ATC of producing any output declines with the scale of operation.

Marginal revenue is the change in total revenue due to selling one more unit of the good.

Average revenue is the price per unit sold.

Allocative inefficiency arises when resources are not appropriately allocated and result in deadweight losses.

Price discrimination involves charging different prices to different consumers in order to increase profit.

A cartel is a group of suppliers that colludes to operate like a monopolist.

Rent seeking is an activity that uses productive resources to redistribute rather than create output and value.

Invention is the discovery of a new product or process through research.

Product innovation refers to new or better products or services.

Process innovation refers to new or better production or supply.

Patent laws grant inventors a legal monopoly on use for a fixed period of time.

Exercises for Chapter 10

Consider a monopolist with demand curve defined by P=100–2Q. The MR curve is MR=100–4Q and the marginal cost is MC=10+Q. The demand intercepts are ![]() , the MR intercepts are

, the MR intercepts are ![]() .

.

Develop a diagram that illustrates this market, using either graph paper or an Excel spreadsheet, for values of output

.

.Identify visually the profit-maximizing price and output combination.

Optional: Compute the profit maximizing price and output combination.

Consider a monopolist who wants to maximize revenue rather than profit. She has the demand curve P=72–Q, with marginal revenue MR=72–2Q, and MC=12. The demand intercepts are ![]() , the MR intercepts are

, the MR intercepts are ![]() .

.

Graph the three functions, using either graph paper or an Excel spreadsheet.

Calculate the price she should charge in order to maximize revenue. [Hint: Where the MR=0.]

Compute the total revenue she will obtain using this strategy.

Suppose that the monopoly in Exercise 10.2 has a large number of plants. Consider what could happen if each of these plants became a separate firm, and acted competitively. In this perfectly competitive world you can assume that the MC curve of the monopolist becomes the industry supply curve.

Illustrate graphically the output that would be produced in the industry?

What price would be charged in the marketplace?

Optional: Compute the gain to the economy in dollar terms as a result of the DWL being eliminated [Hint: It resembles the area ABF in Figure 10.14].

In the text example in Table 10.1, compute the profit that the monopolist would make if he were able to price discriminate, by selling each unit at the demand price in the market.

A monopolist is able to discriminate perfectly among his consumers – by charging a different price to each one. The market demand curve facing him is given by P=72–Q. His marginal cost is given by MC=24 and marginal revenue is MR=72–2Q.

In a diagram, illustrate the profit-maximizing equilibrium, where discrimination is not practiced. The demand intercepts are

, the MR intercepts are

, the MR intercepts are  .

.Illustrate the equilibrium output if he discriminates perfectly.

Optional: If he has no fixed cost beyond the marginal production cost of $24 per unit, calculate his profit in each pricing scenario.

A monopolist faces two distinct markets A and B for her product, and she is able to insure that resale is not possible. The demand curves in these markets are given by PA=20–(1/4)QA and PB=14–(1/4)QB. The marginal cost is constant: MC=4. There are no fixed costs.

Graph these two markets and illustrate the profit maximizing price and quantity in each market. [You will need to insert the MR curves to determine the optimal output.] The demand intercepts in A are

, and in B are

, and in B are  .

.In which market will the monopolist charge a higher price?

A concert organizer is preparing for the arrival of the Grateful Living band in his small town. He knows he has two types of concert goers: One group of 40 people, each willing to spend $60 on the concert, and another group of 70 people, each willing to spend $40. His total costs are purely fixed at $3,500.

Draw the market demand curve faced by this monopolist.

Draw the MR and MC curves.

With two-price discrimination what will be the monopolist's profit?

If he must charge a single price for all tickets can he make a profit?

Optional: A monopolist faces a demand curve P=64–2Q and MR=64–4Q. His marginal cost is MC=16.

Graph the three functions and compute the profit maximizing output and price.

Compute the efficient level of output (where MC=demand), and compute the DWL associated with producing the profit maximizing output rather than the efficient output.