In analyzing perfect competition we emphasized the difference between the industry and the individual supplier. The individual supplier is an atomistic unit with no market power. In contrast, a monopolist has a great deal of market power, for the simple reason that a monopolist is the sole supplier of a particular product and so really is the industry. The word monopoly, comes from the Greek words monos, meaning one, and polein meaning to sell. When there is just a single seller, our analysis need not distinguish between the industry and the individual firm. They are the same on the supply side.

Furthermore, the distinction between long run and short run is blurred, because a monopoly that continues to survive as a monopoly obviously sees no entry or exit. This is not to say that monopolized sectors of the economy do not evolve, they do. Sometimes they die, sometimes they evolve in a different role. For example, when digital cameras entered the market place in the eighties the Polaroid Land camera (which printed film straight out of the camera) 'died' because the demand side of the market lost interest. The Blackberry 'smart' phone had a virtual monopoly on this product into the new millennium until Apple and Nokia entered the market.

A monopolist is the sole supplier of an industry's output, and therefore the industry and the firm are one and the same.

Monopolies can exist and exert their dominance in the market place for several reasons; scale economies, national policy, successful prevention of entry, research and development combined with patent protection.

Natural monopolies

Traditionally, monopolies were viewed as being 'natural' in some sectors of the economy. This means that scale economies define some industries' production and cost structures up to very high output levels, and that the whole market might be supplied at least cost by a single firm.

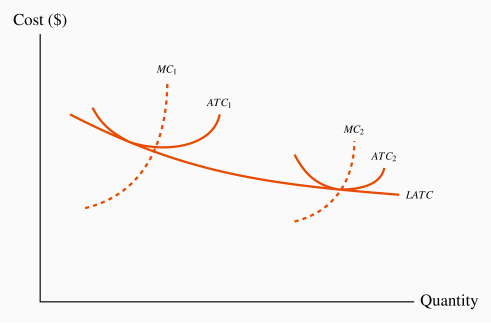

Consider the situation depicted in Figure 10.1. The long-run ATC curve declines indefinitely. There is no output level where average costs begin to increase. Imagine now having several firms, each producing with a plant size corresponding to the short-run average cost curve  , or alternatively a single larger firm using a plant size denoted by

, or alternatively a single larger firm using a plant size denoted by  . The small firms in this case cannot compete with the larger firm because the larger firm has lower production costs and can undercut the smaller firms, and supply the complete market in the process. Such a scenario is termed a natural monopoly.

. The small firms in this case cannot compete with the larger firm because the larger firm has lower production costs and can undercut the smaller firms, and supply the complete market in the process. Such a scenario is termed a natural monopoly.

Natural monopoly: one where the ATC of producing any output declines with the scale of operation.

Electricity distribution in some of Canada's provinces is in the hands of a single supplier – Hydro Quebec or Hydro One in Ontario, for example. These distributors are natural monopolies in the sense described above: Unit distribution costs decline with size. In contrast, electricity production is not 'naturally' a monopoly. Other suppliers were once thought of as 'natural' monopolies also, but are no longer. Bell Canada was considered to be a natural monopoly in the era of land lines: It would not make economic sense to run several sets of phone lines to every residence. But that was before the arrival of cell phones, broadband and satellites. Canada Post was also thought to be a natural monopoly, until the advent of FEDEX, UPS and other couriers proved otherwise. Invention can compete away a 'natural' monopoly.

In reality there are very few pure monopolies. Facebook, Microsoft, Amazon, Apple, Netflix and Google may be extraordinarily dominant in their markets, but they are not the only suppliers of the services or products that they offer. There exist other products that are similar.

National and Provincial Policy

Government policy can foster monopolies. Some governments are, or once were, proud to have a 'national carrier' in the airline industry – Air Canada in Canada or British Airways in the UK. The mail service was viewed as a symbol of nationhood in Canada and the US: Canada Post and the US Postal system are national emblems that have historic significance. They were vehicles for integrating the provinces or states at various points in the federal lives of these countries.

In the modern era, most of Canada's provinces have decided to create a provincial monopoly crown corporation for the sale of cannabis. But competition abounds in the form of an illegal market.

The down side of such nationalist policies is that they can be costly to the taxpayer. Industries that are not subject to competition can become fat and uncompetitive: Managers have insufficient incentives to curtail costs; unions realize the government is committed to sustain the monopoly and push for higher wages than under a more competitive structure, and innovation may be less likely to occur.

Maintaining barriers to entry

Monopolies can continue to survive if they are successful in preventing the entry of new firms and products. Patents and copyrights are one vehicle for preserving the sole-supplier role, and are certainly necessary to encourage firms to undertake the research and development (R&D) for new products.

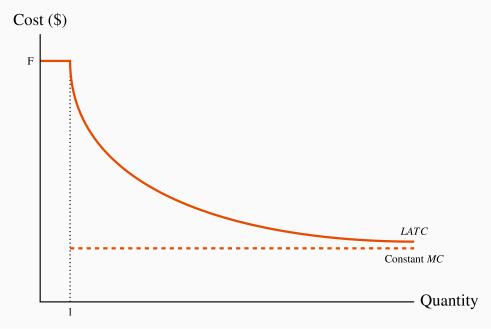

Many corporations produce products that require a large up-front investment; this might be in the form of research and development, or the construction of costly production facilities. For example, Boeing or Airbus incurs billions of dollars in developing new aircraft; pharmaceuticals may have to invest a billion dollars to develop a new drug. However, once such an investment is complete, the cost of producing each unit of output may be relatively low. This is particularly true in pharmaceuticals. Such a phenomenon is displayed in Figure 10.2. In this case the average cost for a small number of units produced is high, but once the fixed cost is spread over an ever larger output, the average cost declines rapidly, and in the limit approaches the marginal cost. These production structures are common in today's global economy, and they give rise to markets characterized either by a single supplier or a small number of suppliers.

This figure is useful in understanding the role of patents. Suppose that Pharma A spends one billion dollars in developing a new drug and has constant unit production costs thereafter, while Pharma B avoids research and development and simply imitates Pharma A's product. Clearly Pharma B would have a LATC equal to its LMC, and would be able to undercut the initial developer of the drug. Such an outcome would discourage investment in new products and the economy at large would suffer as a consequence. Economies would be worse off if protection is not provided to the developers of new products because, if such protection is not offered, potential developers will not have the incentive to incur the up-front investment required.

While copyright and patent protection is legal, predatory pricing is an illegal form of entry barrier, and we explore it more fully in Chapter 14. An example would be where an existing firm that sells nationally may deliberately undercut the price of a small local entrant to the industry. Airlines with a national scope are frequently accused of posting low fares on flights in regional markets that a new carrier is trying to enter.

Political lobbying is another means of maintaining monopolistic power. For example, the Canadian Wheat Board had fought successfully for decades to prevent independent farmers from marketing wheat. This Board lost its monopoly status in August 2012, when the government of the day decided it was not beneficial to consumers or farmers in general. Numerous 'supply management' policies are in operation all across Canada. Agriculture is protected by production quotas. All maple syrup in Quebec must be marketed through a single monopoly supplier.

Critical networks also form a type of barrier, though not always a monopoly. Microsoft's Office package has an almost monopoly status in word processing and spreadsheet analysis for the reason that so many individuals and corporations use it. The fact that we know a business colleague will be able to edit our documents if written in Word, provides us with an incentive to use Word, even if we might prefer Wordperfect as a vehicle for composing documents. We develop the concept of strategic entry prevention further in Chapter 11.