Imperfect competitors can be defined by the number of firms in their sector, or the share of total sales going to a small number of suppliers. They can also be defined in terms of the characteristics of the demand curves they all face. A perfect competitor faces a perfectly elastic demand at the existing market price, and this is the only market structure to have this characteristic. In all other market structures suppliers effectively face a downward-sloping demand. This means that they have some influence on the price of the good, and also that if they change the price they charge, they can expect demand to reflect this in a predictable manner. So, in theory, we can classify all market structures apart from perfect competition as being imperfectly competitive. In practice we use the term to denote firms that fall between the extremes of perfect competition and monopoly.

Imperfectly competitive firms face a downward-sloping demand curve, and their output price reflects the quantity sold.

The demand curve for the firm and industry coincide for the monopolist, but not for other imperfectly competitive firms. It is convenient to categorize the producing sectors of the economy as either having a relatively small number of participants, or having a large number. The former market structures are called oligopolistic, and the latter are called monopolistically competitive. The word oligopoly comes from the Greek word oligos meaning few, and polein meaning to sell.

Oligopoly defines a market with a small number of suppliers.

Monopolistic competition defines a market with many sellers of products that have similar characteristics. Monopolistically competitive firms can exert only a small influence on the whole market.

The home appliance industry is an oligopoly. The prices of KitchenAid appliances depend not only on their own output and sales, but also on the prices of Whirlpool, Maytag and Bosch. If a firm has just two main producers it is called a duopoly. Canadian National and Canadian Pacific are the only two major rail freight carriers in Canada; they thus form a duopoly. In contrast, the local Italian restaurant is a monopolistic competitor. Its output is a package of distinctive menu choices, personal service, and convenience for local customers. It can charge a different price than the out-of-neighbourhood restaurant, but if its prices are too high local diners may travel elsewhere for their food experience, or switch to a different cuisine locally. Many markets are defined by producers who supply similar but not identical products. Canada's universities all provide degrees, but they differ one from another in their programs, their balance of in-class and on-line courses, their student activities, whether they are science based or liberal arts based, whether they have cooperative programs or not, and so forth. While universities are not in the business of making profit, they certainly wish to attract students, and one way of doing this is to differentiate themselves from other institutions. The profit-oriented world of commerce likewise seeks to increase its market share by distinguishing its product line.

Duopoly defines a market or sector with just two firms.

These distinctions are not completely airtight. For example, if a sole domestic producer is subject to international competition it cannot act in the way we described in the previous chapter – it has potential, or actual, competition. Bombardier may be Canada's sole rail car manufacturer, but it is not a monopolist, even in Canada. It could best be described as being part of an international oligopoly in rail-car manufacture. Likewise, it is frequently difficult to delineate the boundary of a given market. For example, is Canada Post a monopoly in mail delivery, or an oligopolist in hard-copy communication? We can never fully remove these ambiguities.

The role of cost structures

A critical determinant of market structure is the way in which demand and cost interact to determine the likely number of market participants in a given sector or market. Structure also evolves over the long run: Time is required for entry and exit.

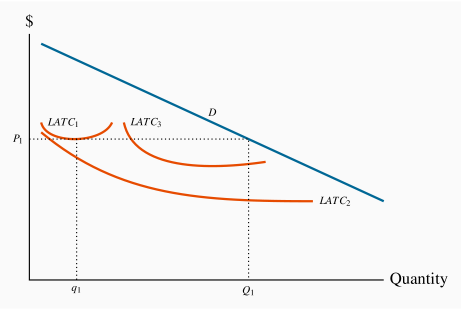

Figure 11.1 shows the demand curve D for the output of an industry in the long run. Suppose, initially, that all firms and potential entrants face the long-run average cost curve LATC1. At the price P1, free entry and exit means that each firm produces q1. With the demand curve D, industry output is Q1. The number of firms in the industry is N1 (=Q1/q1). If q1, the minimum average cost output on LATC1, is small relative to D, then N1 is large. This outcome might be perfect competition (N virtually infinite), or monopolistic competition (N large) with slightly differentiated products produced by each firm.

Instead, suppose that the production structure in the industry is such that the long-run average cost curve is LATC2. Here, scale economies are vast, relative to the market size. At the lowest point on this cost curve, output is large relative to the demand curve D. If this one firm were to act like a monopolist it would produce an output where MR=MC in the long run and set a price such that the chosen output is sold. Given the scale economies, there may be no scope for another firm to enter this market, because such a firm would have to produce a very high output to compete with the existing producer. This situation is what we previously called a "natural" monopolist.

Finally, the cost structure might involve curves of the type LATC3, which would give rise to the possibility of several producers, rather than one or very many. This results in oligopoly.

It is clear that one crucial determinant of market structure is minimum efficient scale relative to the size of the total market as shown by the demand curve. The larger the minimum efficient scale relative to market size, the smaller is the number of producers in the industry.