In addition to using reading comprehension skills such as predicting, visualizing, “talking to the text,” skimming a textbook before reading, and noting patterns and context clues as featured in lessons one,two, and three, another strategy called “close reading” is helpful. This is popular with literature professors; however, the skills involved in close reading are applicable to any complex reading assignment.

I usually begin my close reading instructions with a visual demonstration. Perhaps describing it here will help you, too.

Since this kind of comprehension starts with knowing nothing about the elements of a story, novel, poem, or essay, I stand with my arms spread wide.

I then discuss, briefly, each element of a work starting with the title as a place to begin comprehension, while slowly moving my arms toward one another, a few inches per element.

Titles, for starters, particularly of non-fiction works, usually tell you precisely what the main idea, or thesis, is. For example, a book about “The History of the Roman Empire” usually gives you just that–the history of the Roman Empire.

This is not usually true, however, for works of fiction, for which inference is the key to comprehension. For example, “Story of an Hour,” by Kate Chopin, while it might seem to be something about time, also suggests it is about something other than a clock ticking away seconds and minutes, and indeed it is.

I next add the author, as this might aid comprehension. For example, most students are familiar with Stephen King, who writes in the horror genre. Knowing this element brings the arms in a bit closer as the reader will know to anticipate (and predict) a horror story with a lot of plot twists and turns in some horrible ways. Prediction has begun.

Next, I briefly discuss how knowing about the remaining elements – plot, characters, and setting – help the reader close in on meaning enough to be able to discuss the theme or themes of the work with reasonable evidence to support one’s conclusion.

This visual of the arms getting closer together can continue through a discussion of close reading of small passages, individual sentences, and even specific words. Each level of careful attention and thought helps a reader “read between the lines” when meaning is not overtly stated, when themes are inferred rather than explained outright.

Exercises 4.1 and 4.2 demonstrate how we already engage in this kind of thinking–for different purposes.

UNIT 3, EXERCISE 4.1

Idioms are good examples of inference, or “reading between the lines.” They also employ the comparison skill called metaphor (comparing two things without using the terms “like” or “as”).

Write out as many meanings for the list of idioms, below, as you can.

(Note: for international students: here is an additional reference list, if needed that includes meanings).

Some examples are:

Keep it under your hat.

Over the hill.

Barking up the wrong tree.

Paint the town red.

Lion’s share.

Turned a deaf ear.

Up a creek without a paddle.

Eyes are bigger than your stomach.

Put your nose to the grindstone.

Keep your shoulder to the wheel.

Running on empty.

Too many irons in the fire.

Spitting image.

Born with a silver spoon in his mouth.

Wild goose chase.

Clear sailing.

Walking on cloud nine.

UNIT 3, EXERCISE 4.2

Captions and titles for pictures, art, and sculpture are also examples of the use of inference. At Lane, we have a number of sculptures on the grounds as well as a small art gallery of student work. Take a “mini field trip” around campus or if the weather is bad, access the list of art works at Lane. Choose three artworks to re-name, using inference.

UNIT 3, EXERCISE 4.3

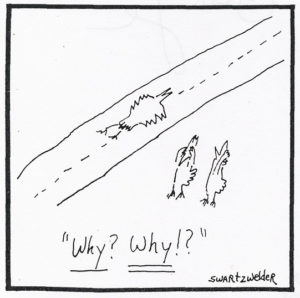

Cartoons, especially editorial cartoons, also make good use of inference skills.

For the cartoon, below, answers the questions about each of its elements to get to the meaning. Cartoons, like other forms of art, include additional visual elements such as facial expressions, and setting. Many of us are able to comprehend cartoons within a few seconds just because we have so many inference skills already in our “hard drives,” so to speak, but examining them now will be a good reminder of how to comprehend complex subject matter–by close examination of all of the elements.

- Setting:

- Subject (what’s going on):

- Facial expression(s):

- Quote:

- Meaning of quote (inference):