8.4: Intersectionality and Reproductive Justice - Part I

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 143331

- Kay Fischer

History of Reproductive Justice

On June 24, 2022 the United States Supreme Court ruled 6 to 3 to overturn Roe v. Wade, ending fifty years of the right to access safe and legal abortion. However, for poor women and women of color (and all reproducing persons of any gender background), access to safe abortions has been a challenge even before this Supreme Court ruling. Furthermore, the issue of only legality, as abortion rights have been framed in white feminist movements, was too narrow for women of color who have historically faced and continue to meet the interlocking systems of power that attempt to take away agency over their own bodies.

Instead, the reproductive justice movement, led by women of color, applies an intersectional lens and expands the concerns beyond the limited framing of pro-choice v. pro-life. The intersectionality framing offers a broader understanding of restrictions placed on reproductive actions, examining the ways oppressions related to race, gender, class, and sexuality operate simultaneously. And therefore, “solutions require a holistic approach” (Ross and Solinger, 2017, p. 75). According to reproductive justice movement leader, Loretta Ross, who outlined the following in her book with Rickie Solinger, Reproductive Justice: An Introduction (2017), reproductive justice has three primary values:

- the right not to have a child

- the right to have a child

- and the right to parent children in safe and healthy environments

The authors write, "In addition, reproductive justice demands sexual autonomy and gender freedom for every human being. The problem is not defining reproductive justice but achieving it" (p. 65).

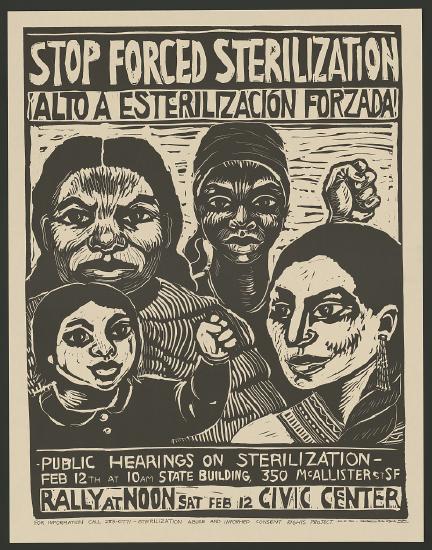

In the following two sections, we’ll examine the history of reproductive control and impacts of oppressive policies and practices that particularly target women of color. First, we should understand that options available to fertile people have always been limited by resources they have access to or don’t. Secondly, we’ll examine the specific ways that the goals of white nationhood and expansion have informed the reproductive and parenting experiences of communities of color. Reproductive injustices include rape, forced sterilization, inaccessibility to contraception, including abortion, separation of children from their parents, loss of pregnancies due to genocidal wars, forced removals and marches, antimiscegenation laws and exclusionary immigration policies that prevented the formation of a second generation of immigrants from Asia, and more. Such barriers placed in the past continue to impact many communities today (Ross and Solinger, 2017, pp. 13-14). Lastly, a reproductive justice framing also highlights instances of resistance and responses to such policies and practices led by women of color. This includes organizing to end racially based sterilization programs, access to full reproductive healthcare, and objecting welfare policies that punish poor women for “illegitimate” motherhood.

Reproductive Control and Resistance in Early U.S. History

Let’s begin in the colonial period. European settler-colonist elites from this era were primarily concerned with defining the members of this new nation: who did they want to be considered “American” and who did they want to exclude. Population growth became “...crucial for establishing, developing, and enlarging, and defending their land claims, their accumulation of wealth, and their political control of the settled territories” (Ross and Solinger, 2017, p. 18). Coinciding with this colonial project was the mass removal of Native American populations which interfered with European expansion, as well as increased numbers of enslaved labor by Africans, which was necessary to achieve a rapid accumulation of wealth. The strategy was to control the population growth of African Americans and expunge the population of Native communities, a dual sided approach with a goal of population control, a method of limiting the population numbers of a specific group. In the context of a white supremacist nation, population control was also “a crucial aspect of establishing ‘the legal meanings of racial difference’” (p.18).

A 1662 Virginia Colony law overturned an English common law that defined the status of children according to the father. This allowed the children of enslaved mothers to be automatically enslaved, thereby guaranteeing the continuation of a slavocracy. Enslaved women’s fertility now became “essential, exploitable, colonial resource” and it wasn’t important if her pregnancy resulted from rape or love, “engrossing the holdings of her owner” (Ross and Solinger, 2017, pp. 18-19). Another law passed in 1692 outlawing interracial unions, labeling all mixed race children as “illegitimate” and subjecting them into bonded labor. Such laws required the “complete subordination of enslaved women,” stripping away any sexual, relational, and maternal rights, practically legalizing the rape and abuse of enslaved women by white slave masters. These practices set in place the “...absence of reproductive dignity and safety,” making them “key to definitions and mechanisms of degradation, enslavement, and white supremacy” (p. 19).

Enslaved women would often lose their pregnancies, sometimes “right in the fields,” due to being overworked. They also suffered high infant mortality rates, miscarriages, and stillbirths. Even after giving birth to a newborn, mothers were often unable to produce sufficient breast milk due to inadequate diets, weaning their babies early, thereby resulting in more frequent pregnancies at shorter intervals (Ross and Solinger, 2017, p. 20). Still, women found ways share information on how to control fertility, including effective herbal contraceptives and midwives among them who operated abortions in secret. There were also instances of women killing their newborns in order to resist producing a new slave for the master and “consign a potential child to a life of enslavement” (p. 21). Although painful to read, Ross and Solinger (2017) remind us that, “Each of these acts continued a woman’s claim of full personhood - her linkage of her reproductive life to human freedom” (pp. 20-21).

While invested in the reproduction of enslaved women in order to produce more free laborers, the U.S. did not want that for Native American populations, seeing it in their best interest to terminate the growth of such peoples. The government’s objective was genocidal, which Ross and Solinger (2017) note was “the ultimate population control policy” (p. 22). Christian missionaries also played a significant role, trying to "correct" mothers with European birthing and child-rearing practices. Missionaries directed authority away from women as many tribes were egalitarian or matrilineal and, for example, among the Cherokee, women held political and economic authority (p. 21). The mass removals of Indigenous communities from their homes further west also resulted in the abusive conditions that threatened the wellbeing of pregnant women. Forced to march for days in the cold, with hardly any food or appropriate clothing, many women and their babies died. They were also prevented from practicing any Indigenous rituals associated with health; in fact, one missionary reported that the “‘Troops frequently forced women in labor to continue [marching] until they collapsed and delivered’ surrounded by soldiers” (p. 22).

In contrast, by the 19th century, laws against contraception and abortions reflected ideologies around the importance of “the white mother’s role in making the white nation and the government’s interest in protecting her fertility.” The white mother was a symbol of white nationhood, “...the nation’s most precious resource” (Ross and Solinger, 2017, p. 23). Before the American Revolution and for the first half of the 19th century, white women actually had access to legal abortions. But beginning in the 1820s, physicians began controlling the “lucrative domains of gynecology and obstetrics” and successfully lobbied to end access to abortion services. By the end of the 19th century, all states had outlawed abortion (p. 24). The federal Comstock Law of 1873 even allowed officials to surveil the mail, checking for contraceptives, putting control of fertility strictly into the hands of white male doctors.

After the Civil War, Black people began migrating out of the South during the first wave of the Great Migration (1910 - 1930). For Black women, it meant “moving away from sexually predatory white men who rarely faced legal sanctions when they attacked women of color” (Ross and Solinger, 2017, p. 27). Migration also translated as an act of protecting their children from daily terrorization by white supremacy, even as they faced a different type of racism and discrimination in these new areas. Still, in urban centers of the north, Black women had improved access to contraception and abortion services.

In the meantime, Native American women were battling coercion from the U.S. government to send their children to boarding schools, where Native children were supposedly raised to become “civilized.” In reality, these schools inflicted cruel measures to suppress tribal languages and cultural practices, a hegemonic project forcing children to assimilate and internalize white-centered American culture (Ross and Solinger, 2017, p. 27). When parents resisted having their children taken away, the government withheld food rations and called the police. An agent to the Mescalero Apache described how police would raid tribal camps to seize children. He witnessed parents running with their children into the mountains and the police having to chase and capture the children “like so many wild rabbits.” Women lamented out loud, and their children were “almost out their wits with fright” (p. 28).

As Indigenous families faced cruel genocidal practices by the U.S. government, population control policies continued to be carried out in order “to distinguish between the value of women’s reproductive bodies by race, class, and ethnicity” (Ross and Solinger, 2017, p. 28). Immigrants from Europe and Asia continued to meet the labor requirements of an industrialized nation, but immigration and welfare officials instituted policies that prevented the growth of such communities. For Asian immigrants, this meant exclusion laws, the first major one being the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the first major immigration law enacted on large-scale exclusion based on race and class (Lee 2015, p. 90). As a result, Chinese laborers and wives of Chinese laborers were prevented from immigrating to the U.S., dramatically impacting the gender balance of this community. Women only made up 3.6% of the Chinese population in 1880 and 12.6% in 1920. Such gendered restrictions and antimiscegenation laws (preventing marriage between Chinese men and white women) practically guaranteed that Chinese men could not procreate in the U.S. As a result, hardly any Chinese babies were granted birthright citizenship during this era (p. 29).

Eugenicists and Forced Mass Sterilization

By the 20th century, Jim Crow was full blown in the South where neighborhoods, schools, swimming pools, and employment were all racially segregated. Antimiscegenation laws were used to separate the races, “making interracial sex and procreation a crime in many states” (Ross and Solinger, 2017, p. 30). Eugenics began to be popular, reinstating much bolder claims of white racial superiority and that it was possible to reproduce “the ‘best examples’ of humanity and eradicate ‘negative expressions' of human life” (p. 30). Genetic inferiority was blamed for larger social issues including criminality, poverty, prostitution, and mental illness, and eugenicists eagerly believed that removing supposedly inferior genes would “foster a superior human race free of these social ills” (Rojas, 2009, p. 98). Groups considered undesirable were nonwhites, the poor, and anybody with psychological, physical, and cognitive disabilities. Politicians began to create laws that criminalized interracial relationships and encouraged the sterilization of “socially inadequate persons,” thereby defining “racial difference and racial hierarchy as primary goals of the government” (Ross and Solinger, 2017, pp. 30-31).

The Immigration Act of 1924 or the National Origins Act put nationality caps on immigration meant to “protect the white identity of the United States” (Ross and Solinger, 2017, p. 31). The law included a supposed “scientific” study of the origins of the populations to use as a guide in determining who was allowable or not, completely excluding Asians and their descendants, descendants of “slave immigrants” and “American aborigines”; such restrictions continue to impact the racial and ethnic origins of populations born in the U.S. (p. 32).

Eugenicists also enacted policies that promoted contraception and sterilization to suppress the fertility of key groups. For example, birth control clinics aimed at poor African Americans were developed by public health officials who believed it was a service to “the public good” to decrease Black fertility. Sterilization became an active public health measure during the Depression, especially after the 1927 Supreme Court case, Buck v. Bell had upheld the state’s right to forcibly sterilize someone for “eugenical purposes” (Ross and Solinger, 2017, pp. 33-34). By 1932, more than 26 states passed sterilization laws targeting specific populations including North Carolina, where an estimated 8,000 sterilizations were conducted on people claimed as “mentally deficient persons,” a majority of whom were black (Rojas, 2009, p. 99). By 1970, the Nixon administration established federal family planning programs that targeted inner city communities in response to extremist fears of African American population growth. When the forced sterilization of the Relf sisters (ages 12 and 14) by a government funded family planning clinic became public knowledge, it was discovered that up to 150,000 people were sterilized every year by programs funded with federal dollars.

Sidebar: The Relf Sisters

In 1973, African American sisters from Montgomery, Alabama, Minnie Lee and Mary Alice Relf (ages fourteen and twelve), were unknowingly sterilized at a hospital under the Family Planning Clinic of the Montgomery Community Action Committee, funded by the U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW). Once this case gained the national spotlight, it was soon uncovered that up to 150,000 people had been sterilized each year by programs funded by this government agency (Rojas, 2009, p. 100). This injustice started when the Relf family moved to a public housing project and soon asked to participate in its family planning program. Katie, the oldest, was seventeen in 1971 when she was forced to accept (without her mother’s presence), an intrauterine device (IUD). Minnie Lee and Mary Alice, who were mentally disabled, received Depo-Provera birth control injections, still at its experimental stage in the 1970s. Later studies showed that Depo-Provera caused cancer in lab animals and clinics discontinued the injections. The clinic then decided to replace the injections with sterilization, as it was the only contraceptive method funded by the HEW, but never informed their mother about this change. Mrs. Relf was illiterate and asked to sign with an “X” on a consent form authoring the operation for her daughters, while believing this was to approve her daughters continuing with Depo shots (p. 101).

The Southern Poverty Law Center filed a lawsuit on the family’s behalf in 1974 and also discovered that in addition to hundreds of thousands sterilized without consent, many others were coerced into sterilization as doctors threatened to end access to welfare benefits. The judge ruled against the use of federal dollars for forced sterilizations and the practice of threatening to cut off welfare benefits if women didn’t comply. Rojas cites an argument by Angela Davis who pointed out the “inherent race and class privileges'' within the reproductive rights movement, as there was hesitation by some to support an end to sterilization abuse if it might limit access by middle and upper class white women who might choose sterilization. Davis wrote, “While women of color are urged, at every turn, to become permanently infertile, white women enjoying prosperous economic conditions are urged, by the same forces, to reproduce themselves” (cited in Rojas, 2009, p. 102).

A notable class-action suit that highlighted an instance of targeted forced sterilization was Madrigal v. Quilligan (1975), brought on by ten Chicanas against the Los Angeles County-University of Southern California Medical Center (county hospital). The case brought to light that multiple women of Mexican origin were coerced into signing consent forms while they were in labor or under heavy anesthesia (Ruíz and Sánchez Korrol, 2006, p. 418). None of the women were fluent in English even though they were pressured to sign forms in English, and were either misinformed or simply lied to about the procedure. Some of the tubal ligations took place even after the women clearly stated that they did not want to be sterilized. For example, Dolores Madrigal refused multiple offers to be sterilized, but presented with consent forms while in labor, she finally signed because she was misinformed that the operation could be reversed easily. For Jovita Rivera, she shared that she was intimidated to sign the forms by doctors who expressed that she would be a burden on the taxpayers (p. 416). Georgina Hernandez didn’t know she was sterilized until weeks later, because she refused such procedures, despite the doctor’s claim that she couldn’t properly care for her children as “a poor Mexican” (p. 417).

The plaintiffs sought financial compensation and for hospitals to provide consent forms in Spanish, arguing that their civil and constitutional rights to procreate had been violated. The judge displayed clear racial bias by making derogatory statements during the case, for instance, claiming, “We all know that Mexicans love their families” (Ruíz and Sánchez Korrol, 2006, p. 418). Even after ample testimony and evidence presented on the lasting damaging effects of this practice, the judge ruled in favor of the County Hospitals and its doctors, blaming the women and their culture, ignoring the defendants’ rights and the moral obligation of medical practitioners (p. 418-419). He claimed that the doctors had acted in good faith and attributed it to miscommunication. Even though the case was lost, Chicana activists highlighted a success in raising public awareness of coerced sterilization as a serious discriminatory act. Since, the California Department of Health reexamined its sterilization guidelines to “ensure the right of informed consent,” also issuing booklets in both English and Spanish (p. 419).

Sidebar: More on Madrigal v. Quilligan

For details about the Madrigal v. Quilligan case, check out the Library of Congress's Latinx Resource Guide on the case - 1978 Madrigal v. Quilligan

Puerto Rican operaciones

Another group of Latina/x targets of experimentation and sterilization were Puerto Ricans. According to Elena R. Gutierrez, Puerto Ricans “served as a laboratory for American contraceptive policies and products,” including contraceptive foams, IUDs, and pills (Rojas, 2009, p. 99). Most horrific was the jointly sponsored (U.S. and Puerto Rico) sterilization program, operaciones, starting in the 1930s. By framing Puerto Rican and Latina women as “hyperfertile,” proponents theorized that a population reduction program in Puerto Rico would “improve its long-impoverished economy” and soon hospitals began to routinely perform tubal ligations by obtaining their consent either during labor or right after the birth (p. 102). Gutierrez points out that by 1965 already 35% of Puerto Rican women had been sterilized, a majority only in their twenties. Puerto Rican women still have some of the highest rates of sterilization to this day, with many who underwent the procedure expressing no regrets (Ruiz and Sánchez Korrol, 2006, p. 725).

Coerced Sterilization of Indigenous Women

The federally funded Indian Health Services (IHS) were particularly aggressive about the sterilization of Native American communities. The exact numbers are difficult to ascertain, since the IHS didn’t keep accurate records, but Women of All Red Nations (WARN) estimated that the rate of female sterilization was as high as 80% on some reservations, and some research uncovered that between 1968 and 1982, around 42% of Indigenous women of childbearing age were sterilized (Ross and Solinger, 2017, p. 50). According to Andrea Smith, professor of Ethnic Studies, UC Riverside, this program started in 1970. Connie Uri, a Cherokee/Choctow doctor, was one of the first to bring this issue to light after hearing from many Native American patients that they had been sterilized without informed consent (Smith, 2015, pp. 81 - 82). Upon pressuring Congress to investigate this issue, the General Accounting Office (GAO) released a report in 1976 revealing that of the 4 out of 12 areas studied, 3,001 Native women of childbearing age had been sterilized between 1973 and 1976, 36 of the women under the age of 21 “despite a court-ordered moratorium on such procedures” (p. 82). Some women reported getting sterilized to treat a headache or sterilized when they went to the doctors to get a tonsillectomy (p. 84).

The GAO report also discovered that IHS was not in compliance with their own regulations, such as consent forms not indicating that the subject had a right to withdraw consent. The U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) regulations were problematic as well, for example eliminating a requirement that a patient seeking sterilization must be orally informed that no federal benefits could be threatened to be withheld if they decided not to accept sterilization. HEW also didn’t require the signature of the patient on the consent forms, instead relying on the word of the doctors (Smith, 2015, p. 84).

Sterilizations in Immigration Detention Centers

As recently as 2020, there have been allegations of continued forced sterilization practices in U.S. institutions. Dawn Wooten, a licensed practical nurse who was employed by the Irwin County Detention Center (ICDC) in Georgia became a whistleblower when she accused the ICDC of sterilizing women at the immigration detention center without informed consent. She described numerous accounts of medical abuse, including refusing to test for COVID-19, refusing to provide medication to detainees, and forced hysterectomies. She began to get concerned when noticing a particularly high number of detained women receiving hysterectomies from a doctor known as the “uterus collector.” Wooten stated,

Everybody he sees has a hysterectomy—just about everybody. He’s even taken out the wrong ovary on a young lady [detained immigrant woman]. She was supposed to get her left ovary removed because it had a cyst on the left ovary; he took out the right one. She was upset. She had to go back to take out the left and she wound up with a total hysterectomy. She still wanted children.… she said she was not all the way out under anesthesia and heard him [doctor] tell the nurse that he took the wrong ovary (Project South, 2020).

Maya Manian, professor of law, further notes that this is not the only time immigrant detainees had their reproductive choices taken away, bringing up the case of former Office of Refugee Resettlement Director, Scott Lloyd, who attempted to prevent teen migrants from accessing abortions, even when their pregnancies were due to rape (Manian 2020).

Unfortunately, this section only offers a sample of forced sterilization practices in the U.S., expressing a pattern of human rights violations. Medical professionals and government officials continue to make unethical decisions on behalf of vulnerable women with practically no political voice, simply because of their preconceived notions around race, gender, class, and immigration status.