6.3: Whiteness- White Privilege, White Supremacy, and White Fragility

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 43483

- Erika Gutierrez, Janét Hund, Shaheen Johnson, Carlos Ramos, Lisette Rodriguez, & Joy Tsuhako

- Long Beach City College, Cerritos College, & Saddleback College via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)

Whiteness

As Isabel Wilkerson describes in her 2020 book, Caste, white is a uniquely American category, constructed during the Trans Atlantic Slave Trade to characterize that which was not Black. In 1936, Ralph Linton wrote that the last thing a fish would ever notice would be water. Likewise, whiteness has largely been invisible to the modern white world. The invisibility of whiteness is rather unique as compared to the visibility of other racial categories such as Black. This invisibility or normality of whiteness corresponds to white being the "default" race or the notion that whites do not have a race. The uniqueness of whiteness's invisibility lies in the contradictions therein: while whiteness partakes of normality and transparency, it is also dominant, insistently so (Whiteness - Sociology of Race - iResearchNet, 2020).

It is this dominance of whiteness that had made whiteness into something so normal. Eduardo Bonilla-Silva identified this color-blind racism in Racism Without Racists. Bonilla-Silva asserts that there is no doubt that the majority of white people in the U.S. subscribe to the doctrines of color-blind racism. Bonilla-Silva argues that the rhetoric of color-blind racism as "the current and dominant racial ideology in the United States, constructs a social reality for people of color in its practices, which are subtle, institutional, and apparently nonracial" (p. 3, 2007). He argues further that this race rhetoric supports a racial hierarchy that maintains white privilege and superiority; race and racism are structured into the totality of our social relations and practices that reinforce white privilege (p. 9, 2007). Further Bonilla-Silva states,

Instead of relying on name calling (niggers, spics, chinks), color-blind racism otherizes softly ("these people are human, too"); instead of proclaiming that God placed minorities in the world in a servile position, it suggests they are behind because they do not work hard enough; instead of viewing interracial marriage as wrong on a straight racial basis, it regards it as "problematic" because of concerns over the children, location, or the extra burden it places on couples (Bonilla-Silva, 2007).

In summary, Bonilla-Silva explains that this color-blind racism perpetuates white dominance and privilege in a more passive way than racism was carried out in the past, and often those who display color-blind racism think they are not racist.

In his book, How the Irish Became white, Noel Ignatiev wrote that white chauvinism amounts to the practice of white supremacy. Ignatiev explains that whiteness rests on the notion of whiteness as equated with a higher social class, thereby eliminating any possibility of class consciousness, awareness of one's class status. White individuals connecting with their whiteness rather than their class commonalities with working class populations leads them to voice, "I may be poor and exploited, but at least I'm white" and not Black (Whiteness - Sociology of Race - iResearchNet, 2020). This is the psychological wage of whiteness that DuBois wrote about in 1935. Whiteness has thus been understood as the absence of color, the absence of culture, the absence of racialization which has also made it extremely difficult for white Americans to really see their whiteness. Yet, of course people of color tend to easily see whiteness.

The final section of this chapter discusses social change and resistance with regards to whiteness. For example, the abolition of whiteness is discussed as necessary for the advancement of humanity. Yet, in order to abolish whiteness, it would need to not only be seen by whites, but be seen as unusual and detrimental to the human race.

White Privilege

It is important to discuss the advantages that U.S. Whites enjoy in their daily lives simply because they are white. Social scientists term these advantages white privilege, informing that whites benefit from being white whether or not they are aware of their advantages (McIntosh, 2007). White privilege is the benefit that white people receive simply by being part of the dominant group. McIntosh wrote that whites are carefully taught not to be aware of their race, rather to be unaware of their unearned assets and advantages. Using the analogy of an invisible knapsack, McIntosh created an initial list of 26 and later expanded to 52 the benefits of whiteness that white Americans carry in their backpacks. For example, whites can usually drive a car at night or walk down a street without having to fear that a police officer will stop them simply because they are white. They can count on being able to move into any neighborhood they desire to as long as they can afford the rent or mortgage. They generally do not have to fear being passed up for promotion simply because of their race. College students who are white can live in dorms without having to worry that racial slurs will be directed their way. White people in general do not have to worry about being the victims of hate crimes based on their race. They can be seated in a restaurant without having to worry that they will be served more slowly or not at all because of their skin color. If they are in a hotel, they do not have to think that someone will mistake them for a bellhop, parking valet, or maid. If they are trying to hail a taxi, they do not have to worry about the taxi driver ignoring them because the driver fears they will be robbed. If they are stopped by the police, they do not have to fear for their lives.

Social scientist Robert W. Terry (1981, p. 120) once summarized white privilege as follows: “To be white in America is not to have to think about it. Except for hard-core racial supremacists, the meaning of being white is having the choice of attending to or ignoring one’s own whiteness” (emphasis in original). For people of color in the United States, it is not an exaggeration to say that race is a daily fact of their existence. Yet whites do not generally have to think about being white. As all of us go about our daily lives, this basic difference is one of the most important manifestations of racial and ethnic inequality in the United States. While most white people are willing to admit that nonwhite people live with a set of disadvantages due to the color of their skin, very few are willing to acknowledge the benefits they receive.

Whites in the United States infrequently experience racial discrimination making them unaware of the importance of race in their own and others’ thinking in comparison to people of color (Konradi & Schmidt, 2004). Many argue racial discrimination is outdated and are uncomfortable with the blame, guilt, and accountability of individual acts and institutional discrimination. By paying no attention to race, people think racial equality is an act of color-blindness, and it will eliminate racist atmospheres (Konradi & Schmidt, 2004). They do not realize the experience of not “seeing” race itself is racial privilege.

Thinking Sociologically

In her 1988 article White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack, Peggy McIntosh introduced the following 26 daily effects of white privilege in her life.

- I can if I wish arrange to be in the company of people of my race most of the time.

- If I should need to move, I can be pretty sure of renting or purchasing housing in an area which I can afford and in which I would want to live.

- I can be pretty sure that my neighbors in such a location will be neutral or pleasant to me.

- I can go shopping alone most of the time, pretty well assured that I will not be followed or harassed.

- I can turn on the television or open to the front page of the paper and see people of my race widely represented.

- When I am told about our national heritage or about “civilization,” I am shown that people of my color made it what it is.

- I can be sure that my children will be given curricular materials that testify to the existence of their race.

- If I want to, I can be pretty sure of finding a publisher for this piece on white privilege.

- I can go into a music shop and count on finding the music of my race represented, into a supermarket and find the staple foods that fit with my cultural traditions, into a hairdresser’s shop and find someone who can cut my hair.

- Whether I use checks, credit cards or cash, I can count on my skin color not to work against the appearance of financial reliability.

- I can arrange to protect my children most of the time from people who might not like them.

- I can swear, or dress in second-hand clothes, or not answer letters, without having people attribute these choices to the bad morals, the poverty, or the illiteracy of my race.

- I can speak in public to a powerful male group without putting my race on trial.

- I can do well in a challenging situation without being called a credit to my race.

- I am never asked to speak for all the people of my racial group.

- I can remain oblivious of the language and customs of persons of color who constitute the world’s majority without feeling in my culture any penalty for such oblivion.

- I can criticize our government and talk about how much I fear its policies and behavior without being seen as a cultural outsider.

- I can be pretty sure that if I ask to talk to “the person in charge,” I will be facing a person of my race.

- If a traffic cop pulls me over or if the IRS audits my tax return, I can be sure I haven’t been singled out because of my race.

- I can easily buy posters, postcards, picture books, greeting cards, dolls, toys, and children’s magazines featuring people of my race.

- I can go home from most meetings of organizations I belong to feeling somewhat tied in, rather than isolated, out-of-place, outnumbered, unheard, held at a distance, or feared.

- I can take a job with an affirmative action employer without having co-workers on the job suspect that I got it because of race.

- I can choose public accommodations without fearing that people of my race cannot get in or will be mistreated in the places I have chosen.

- I can be sure that if I need legal or medical help, my race will not work against me.

- If my day, week, or year is going badly, I need not ask of each negative episode or situation whether it has racial overtones.

- I can choose blemish cover or bandages in “flesh” color and have them more less match my skin.

Which one(s) of these most strike(s) you, and why? Which, if any, are least relevant in our contemporary time period? What other daily effects of white privilege would you add to the list?

Black Like Me

In 1959, John Howard Griffin, a white writer, changed his race. Griffin decided that he could not begin to understand the discrimination and prejudice that African Americans face every day unless he experienced these problems himself. So he went to a dermatologist in New Orleans and obtained a prescription for an oral medication to darken his skin. The dermatologist also told him to lie under a sun lamp several hours a day and to use a skin-staining pigment to darken any light spots that remained.

Griffin stayed inside, followed the doctor’s instructions, and shaved his head to remove his straight hair. About a week later he looked, for all intents and purposes, like an African American. Then he went out in public and passed as Black.

New Orleans was a segregated city in those days, and Griffin immediately found he could no longer do the same things he did when he was white. He could no longer drink at the same water fountains, use the same public restrooms, or eat at the same restaurants. When he went to look at a menu displayed in the window of a fancy restaurant, he later wrote,

I read, realizing that a few days earlier I could have gone in and ordered anything on the menu. But now, though I was the same person with the same appetite, no power on earth could get me inside this place for a meal (Griffin, 1961, p. 42).

Because of his new appearance, Griffin suffered other slights and indignities. Once when he went to sit on a bench in a public park, a white man told him to leave. Later a white bus driver refused to let Griffin get off at his stop and let him off only eight blocks later. A series of stores refused to cash his traveler’s checks. As he traveled by bus from one state to another, he was not allowed to wait inside the bus stations. At times, white men of various ages cursed and threatened him, and he became afraid for his life and safety. Months later, after he wrote about his experience, he was hanged in effigy, and his family was forced to move from their home.

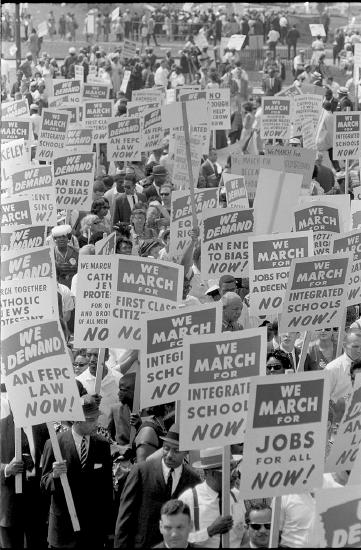

Griffin’s reports about how he was treated while posing as a Black man, and about the way African Americans he met during that time were also treated, helped awaken white Americans across the United States to racial prejudice and discrimination. The Southern civil rights movement, which had begun a few years earlier and then exploded into the national consciousness with sit-ins at lunch counters in February 1960 by Black college students in Greensboro, North Carolina, challenged Southern segregation and changed life in the South and across the rest of the nation.

White Supremacy

“White Supremacist Held Without Bond in Tuesday’s Attack,” the headline read. In August 2009, James Privott, a 76-year-old African American, had just finished fishing in a Baltimore city park when he was attacked by several white men. They knocked him to the ground, punched him in the face, and hit him with a baseball bat. Privott lost two teeth and had an eye socket fractured in the assault. One of his assailants was arrested soon afterwards and told police the attack “wouldn’t have happened if he was a white man.” The suspect was a member of a white supremacist group, had a tattoo of Hitler on his stomach, and used “Hitler” as his nickname. At a press conference attended by civil rights and religious leaders, the Baltimore mayor denounced the hate crime. “We all have to speak out and speak up and say this is not acceptable in our communities,” she said. “We must stand together in opposing this kind of act” (Fenton, 2009, p. 11).

Arising in the late 1860s after slavery was abolished in the U.S, the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) originated in resistance and white supremacy during the Reconstruction Era. Its members' belief in white supremacy has encouraged over a century of hate crime and hate speech. For example in 1924, the KKK marched down Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C.; the KKK had 4 million members out of a national population of about 114 million. In the words of DuBois a century ago: “the Ku Klux Klan is doing a job which the American people, or certainly a considerable portion of them, want done; and they want it done because as a nation they have fear of the Jew, the immigrant, the Negro.”

According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, white nationalist groups espouse white supremacist or white separatist ideologies, often focusing on the alleged inferiority of nonwhites. These supremacist groups include the Ku Klux Klan, neo-Confederate, neo-Nazi, racist skinhead and Christian identity groups. Contemporary white supremacist sympathizers have characterized some of President Trump's Cabinet appointees (e.g., Steve Bannon, Larry Kudlow, and Stephen Miller) as well as violent counter-protestors at the anti-police brutality protests since the George Floyd murder in 2020. The 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia climaxed in the killing of one anti-racist white protester. President Trump shortly thereafter stated that there were good and bad people on both sides. In 2019, following the white supremacist killing of 51 Muslim worshippers in Christchurch, New Zealand, the white supremacist manifesto continued with a shooter in Poway, California at a Jewish synagogue and a gunman in a Walmart store in El Paso, Texas who left 23 dead, mostly Latinx victims.

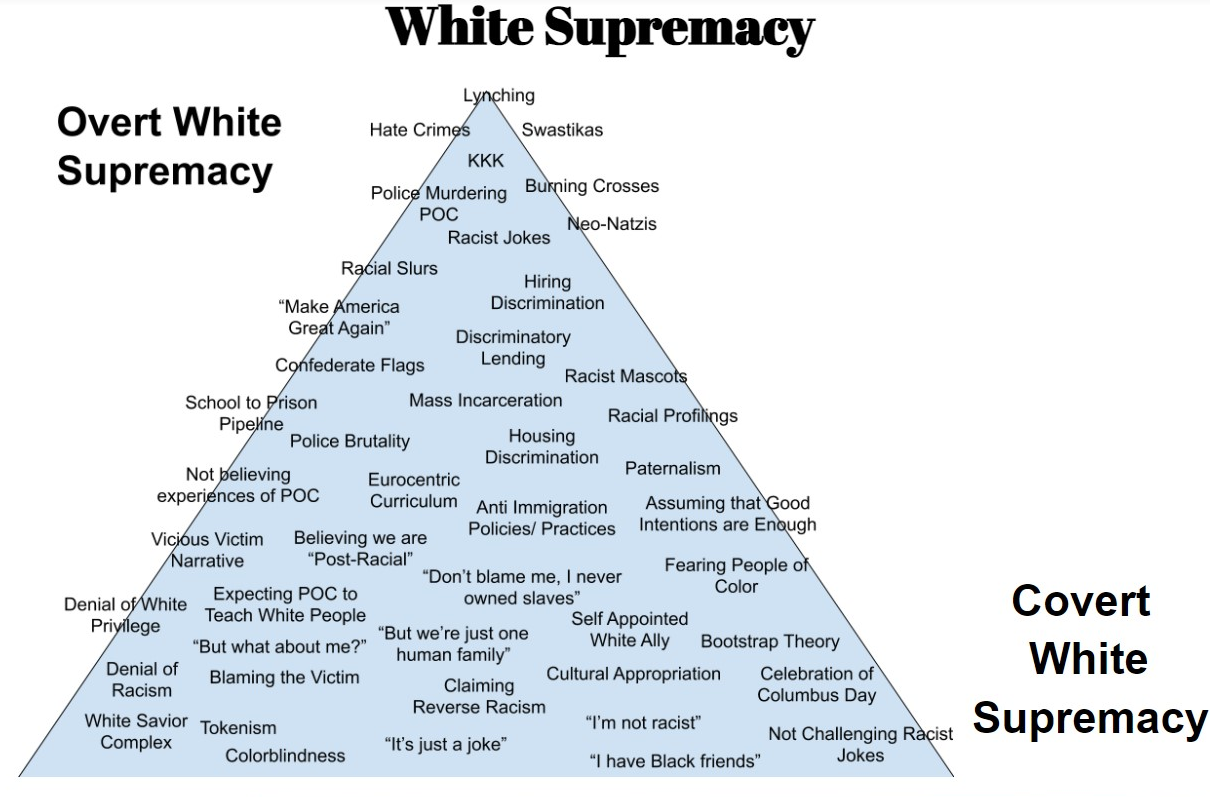

While we are accustomed to thinking about white supremacy in terms of the aforementioned violent hate groups or white nationalist or white power groups, Bonilla-Silva (2007) and DiAngelo (2018) inform us that we should be more concerned with the insidious white supremacy that surrounds our entire society and exists in us, particularly white Americans. According to DiAngelo, white progressives maintain white supremacy - largely through their silence and discomfort with addressing race and racism. Building upon the works of Bonilla-Silva (2007) and Takaki (1993), Hephzibah V. Strmic-Pawl (2015) defines White supremacy as "systematic and systemic ways that the racial order benefits those deemed white and operates to oppress people of color."

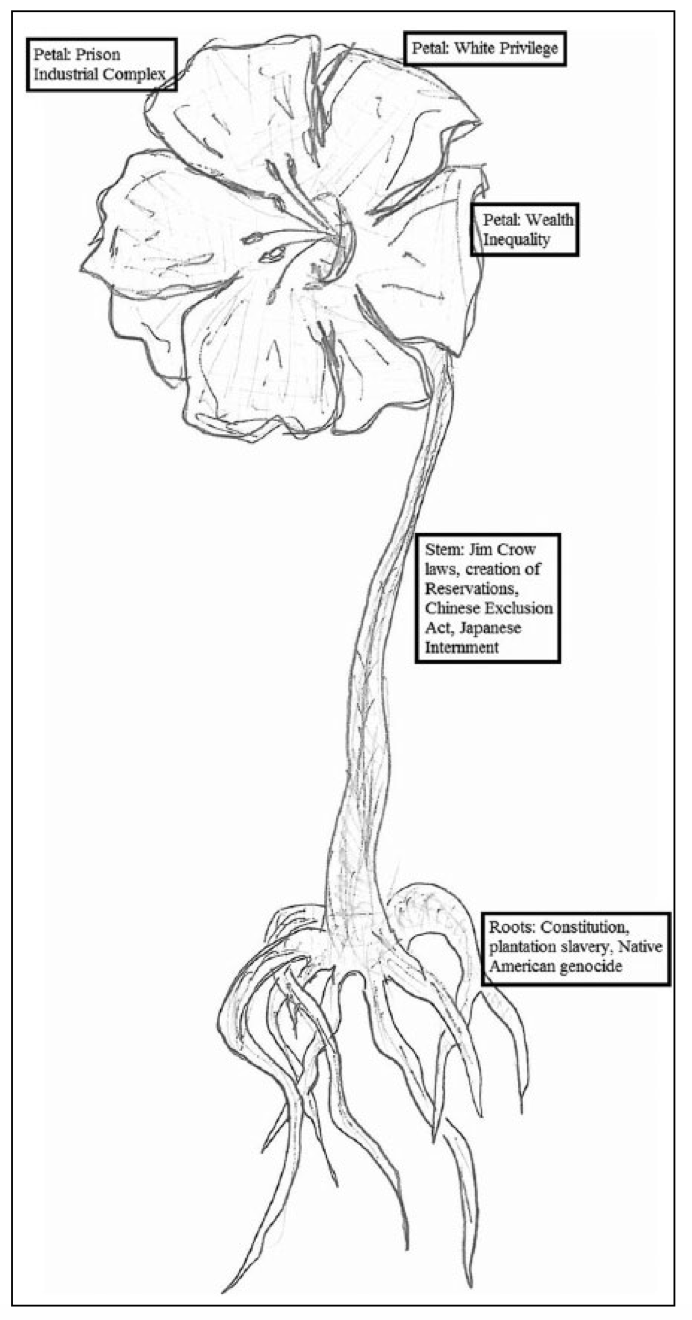

As shown in the figure below, Strmic-Pawl visualized white supremacy in the form of a flower: the roots or foundation of racism in the U.S. (e.g., slavery or Native American genocide), the stem or historical events and processes (e.g., Chinese Exclusion Act or Jim Crow Laws), and the bloom or contemporary U.S. (anti-Asian hate crimes or police brutality such as the killing of George Floyd). Each petal represents a different form of racial inequality. Though petals may fall off, this loss does not kill the plant (of white supremacy). This is akin to the replacement of slavery with Jim Crow and then the prison industrial complex as a way to control Black men, so eloquently explained in Michelle Alexander's The New Jim Crow.

White Fragility

In her introduction of White Fragility: Why It's So Hard for White People To Talk About Racism, Robin DiAngelo (2018) writes:

We consider a challenge to our racial world views as a challenge to our very identities as good, moral people. Thus, we perceive any attempt to connect us to the system of racism as an unsettling and unfair moral offense. The smallest amount of racial stress is intolerable. The mere suggestion that being white has meaning often triggers a range of defensive responses. These include emotions such as anger, fear, and guilt and behaviors such as argumentation, silence, and withdrawal from the stress-inducing situation. These responses work to reinstate white equilibrium as they repel the challenge, return our racial confit, and maintain our dominance within the racial hierarchy. I conceptualize this process as white fragility. The white fragility is triggered by discomfort and anxiety. It is born of superiority and entitlement. White fragility is not weakness per se. In fact, it is a powerful means of white racial control and the protection of white advantage.

Now, the concept of white fragility, an outcome of white people’s socialization into white supremacy and a means to protect, maintain, and reproduce white supremacy, has been injected into both our sociological and societal discussion. According to DiAngelo, society is structured in a way to prevent whites from experiencing racial discomfort, which generally results in whites not having difficult conversations about race - which is exactly the behavior that produces and reproduces white supremacy. DiAngelo posits that "white progressives cause the most daily damage to people of color." Ultimately, DiAngelo explains that white individuals must develop their racial stamina to have difficult conversations about race, actually listen to the voices of people of color, and refuse to remain silent when white supremacy is exposed.

Key Takeaways

- Whiteness is considered normal, transparent, and invisible - in addition to conferring dominance.

- Due to color blindness and a lack of class consciousness, many (white) Americans lack an understanding of whiteness and racial inequality.

- White privilege is something that white Americans benefit from though many are oblivious to the daily effects of white privilege.

- In both covert and overt ways, white supremacy is systemically and systematically impact the racial order, benefiting those deemed white and operatomg to oppress people of color.

- Many whites experience white fragility, an outcome of white people’s socialization into white supremacy and a means to protect, maintain, and reproduce white supremacy.

Contributors and Attributions

- Hund, Janét. (Long Beach City College)

- Johnson, Shaheen. (Long Beach City College)

- Minority Studies (Dunn) (CC BY 4.0)

- A Career in Sociology (Kennedy) (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

- Introduction to Sociology 2e (OpenStax) (CC BY 4.0)

Works Cited

- Alexander, M. (2010). The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. New York, NY: New Press.

- Bonilla-Silva, E. (2007). Racism Without Racists: Color-Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in America. 2nd ed. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- DiAngelo, R. (2018). white Fragility: Why It's So Hard for white People to Talk about Racism. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

- Du Bois, W.E.B. (1977). [1935]. Black Reconstruction: An Essay Toward a History of the Part which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860-1880. Atheneum, NY.

- Fenton, J. (2009, August 20). White supremacist held without bail in Tuesday’s attack. The Baltimore Sun.

- Griffin, J.H. (1961). Black Like Me. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

- Ignatiev, N. (1995). How the Irish Became white. London, UK: Routledge.

- Konradi, A. & Schmidt, M. (2004). Reading Between the Lines: Toward an Understanding of Current Social Problems. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Linton, R. (1936). The Study of Man: An Introduction. New York, NY: Appleton-Century.

- McIntosh, P. (1988). white Privilege and Male Privilege: A Personal Account of Coming to See Correspondences through Work in Women's Studies. Working Paper 189.

- McIntosh, P. 2007. White privilege and male privilege: A personal account of coming to see correspondence through work in women’s studies. In M. L. Andersen & P. H. Collins (Eds.), Race, Class, and Gender: An Anthology. 6th ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

- Southern Poverty Law Center. (n.d.). White Nationalism. Southern Poverty Law Center.

- Strmic-Pawl, H.V. (2015, January). More than a knapsack: The white supremacy flower as a new model for teaching Racism. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity. Volume 1, Issue 1, pp. 192–197.

- Takaki, R. (2008). A Different Mirror: A History of Multicultural America. New York, NY: Back Bay Books/Little Brown & Company.

- Terry, R.W. (1981). The negative impact on white values. In B. P. Bowser & R. G. Hunt (Eds.), Impacts of Racism on white Americans (pp. 119–151). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Wilkerson, I. 2020. Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents. London, UK: Random House.

- Whiteness - Sociology of Race - iResearchNet. (2020). Sociology.