3.1: Latin America- Introducing the Region

- Page ID

- 153977

INTRODUCTION

Latin America and the Caribbean comprise a vibrant region in relation to women’s activism, leadership, and contributions to society, particularly economically and politically, as well as historically and currently. In fact, the organizing efforts of women and people with nonbinary gender identities, transnational solidarity, and state responses have led to increased access to health, education, and other services over the past decades (Cosgrove 2010). These Latin American activists and leaders are uniquely positioned to meet challenges the region faces while continuing to advance their rights. This is because these activists’ culturally ascribed roles as caretakers in the home and the community, as well as their activism and volunteerism during periods of economic and political turmoil—such as conflict, authoritarianism, and neoliberal cuts to state spending, to mention a few—translate directly into important oppositional knowledges and skills such as networking, organizing, cooperating, and listening across difference.

A political doctrine that requires strict obedience to authority at the expense of personal freedom.

Though women and people with other nondominant gender identities and sexualities across the region have achieved much over the past fifty years, there still exist gender gaps: in many spaces, men have benefited from gender hierarchies—the regional equivalent of which is machismo. Gender is best understood relationally; the struggles and experiences of women and people with nondominant gender identities are tied to those of men. Machismo or public and private “exaggerated masculinity” (Ehlers 1991, 3) is a wily term that evades easy definition given its overuse, which stereotypes macho Latin American men who are portrayed as unfaithful and who mistreat the women in their lives. This usage can get deployed to depict men from the Global North as angels compared to their counterparts in the Global South. Obviously this is not the case, as gender-based violence and gender discrimination permeate patriarchal societies around the world, not just Latin America and the Caribbean. Terminology is further complicated by women’s participation in the perpetuation of harmful gender roles and expectations. In the region, men don’t learn gender relations in a vacuum; rather, men, women, and others participate in the maintenance of these cultural roles, even though men generally hold more power and control over resources in patriarchal societies. Sometimes referred to as marianismo—or the trope of the long-suffering mother (e.g., Mary, the mother of Jesus Christ)—is a term that can also reaffirm stereotypes of Latin American women; in this case, the term helps sustain beliefs that women are submissive and should stay in abusive relationships because it’s a woman’s lot to suffer (Ehlers 1991). The machismo/marianismo dichotomy is problematic for a number of reasons. It implies that men and women have equal power, which is not the case given the gender hierarchies in place across the region. And the terms also stereotype male and female roles in ways that do not reflect the complexity or reality of people’s lives and relationships. Due to persistent gender inequalities throughout the region, women and people with nondominant gender identities experience higher levels of poverty and discrimination than men (Craske 2003, 58). There are hidden aspects of the discrimination that women and often those with nonbinary gender identities face as well, such as having to work a double shift—income generation and unpaid care work—or a triple shift, which means income generation, unpaid care work, and community activism. This triple burden (Craske 2003, 67; Cosgrove and Curtis 2017, 131) means women and others from poor communities are often working around the clock to guarantee their families’ survival.

a gender ideology in which certain feminine characteristics are valued above others. These include being submissive, chaste, virginal, and morally strong.

Even the category of “woman” is heterogeneous in Latin America given the intersectional identities that many women hold. First, Latin America and the Caribbean generally have high levels of income inequality, which means that many women are in poverty, creating a gendered ripple effect given women’s responsibilities for children and members of their extended families, particularly the elderly. Second, Latin America and the Caribbean have significant Indigenous and Afro-descendant populations. Often Indigenous and Afro-descendant women face exclusion due to racism throughout the region, which is compounded by sexism. Third, there is quite a lot of population movement throughout the region; often women migrants or refugees as well as those with other nondominant gender identities face challenges their community-of-origin counterparts don’t face, such as lack of what Goett calls “female sociality and mutual aid” (2017, 161) or solidarity that often emerges from kin relations and community life and may not exist for those who are traveling alone from one place to another without documentation or visas. And finally, women aren’t the only people in Latin America who face gender discrimination; women as well as people with nonbinary gender identities and nondominant sexualities have not historically held positions of leadership or control over resources. In fact, people with nondominant gender identities often face worse discrimination and exclusion than cisgender women. In the rest of this introductory chapter, we review regional gender indicators across several areas; then we provide a brief survey of the historical events that inform current opportunities and challenges for women and others; the third section summarizes present-day political and economic policies and their gendered ramifications.

refers to people who originated in or are the earliest-known inhabitants of an area. Also known as First Peoples, First Nations, Aboriginal peoples or Native peoples.

refers to people whose gender identity corresponds to their sex at birth.

GENDER AND REGIONAL INDICATORS

The purpose of this section is to describe some of the opportunities that women in Latin America and the Caribbean face in terms of health, education, employment, political participation, and civil society participation as well as some of the challenges they confront related to sexism and the intersectional effects of other forms of social and economic difference. Gender-based violence affects women across the region; we explore this topic in greater detail in this section as it puts at risk achievements in other areas and indicates pernicious gender inequality and serious intersectional impacts for women and people with nondominant gender identities and sexualities from poor, rural, or other marginalized backgrounds and ethnic identities, which exacerbate exclusion (World Bank 2012, 15).

refers to the interconnected nature of social categories such as race, class, and gender that create overlapping systems of discrimination or disadvantage. The goal of an intersectional analysis is to understand how racism, sexism, and homophobia (for example) interact to impact our identities and how we live in our society.

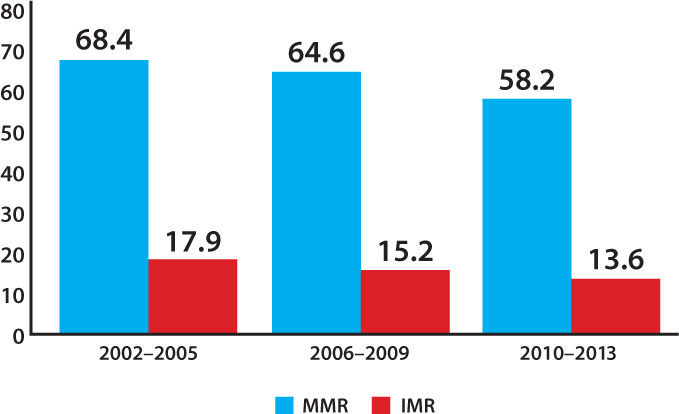

Reproductive health is an important topic for women in Latin America, and yet, women’s access in some parts of the region is at risk due to conservative values colliding with women’s sexuality, which results in oppressive laws, legal frameworks, and enforcement or lack thereof. Many countries in the region provide access to birth control, and the rate of maternal deaths is decreasing, while live births are rising. However, this still hasn’t reached across difference (see figure 7.1). There are large gaps across economic, ethnic, and racial groups (PAHO 2017, 11–12) that affect overall health. This means that poor women, Indigenous women, and others affected by multiple forms of social difference suffer disproportionately; this is further exacerbated by severe antiabortion laws that imprison women who seek abortions as well as doctors who provide them (Guthrie 2019). For example, abortion is prohibited in El Salvador, Nicaragua, Honduras, and the Dominican Republic and very limited in many other countries in the region (Guthrie 2019).

In terms of education, more girls than boys are attending school—primary through secondary—as well as graduating from college in Latin America and the Caribbean. This has led to the overturn of a historical gender advantage for boys and men (World Bank 2012, 15), but these advances are threatened by the fact that in the face of economic or political crisis, families often encourage girls to drop out of school before boys. This is due to the social expectation that boys will grow up to be providers—therefore they need an education to secure a job—whereas girls will be primarily responsible for homes and unpaid care work and therefore not need an education as much as boys (Cosgrove 2010).

There has been a steady increase in women’s participation in the formal economies of Latin America and the Caribbean (World Bank 2012, 20) since the late twentieth century. However, there are a number of factors that continue to impede this participation. At the end of the twentieth century and the beginning of the twenty-first century, new burdens were placed on women. During the crises created by authoritarian military regimes in the 1970s and 1980s, women were often responsible for the survival of their families as men fled the fighting, joined the fighting, or were targeted as subversives. This dire situation saw women working around the clock. Upon the return to democracy across the region in the 1990s, Latin America and the Caribbean were negatively impacted by the structural adjustment policies and neoliberal demands placed on governments by international financial institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. These policies that privatized state enterprises and cut basic food subsidies and welfare programs had gendered impacts on women who were primarily responsible for the survival of their families. When the economic depression of 2008 hit, many men lost their jobs. Women had to generate income in whatever way they could, and again women were primarily responsible for the survival of their families and communities. Finally, women tend to join the informal sector more often than the formal sector where they have fewer legal protections and benefits (World Bank 2012, 21). In the informal sector, women often earn less, have less job security, and are more vulnerable to violence.

When it comes to political leadership and civil society organizing, women have made significant contributions. In the arena of political leadership, there are and have been multiple women presidents across the region over the past couple of decades with multiple women leaders of state in the early twenty-first century. Sixteen out of eighteen countries in Latin America have implemented quotas requiring certain levels of participation of women on electoral lists for political office, and women are drawing close to comprising 30 percent of the parliaments across the region. There are gender inequities across the political sphere (IDEA 2019), such as the fact that in most political party structures men hold higher positions and women congregate at the lower levels, often serving as political organizers at the local level but not holding decision making positions within the parties (IDEA 2019).

Civil society—the wide range of formally registered nongovernmental organizations, community associations, and other organized groups be it at the local or national level—has been led and organized primarily by women for more than a hundred years in Latin America and the Caribbean (Cosgrove 2010). For example, in Argentina, women created a national network of hospitals, schools, and an emergency response system to natural disasters in the late nineteenth century. In El Salvador, women participated in the country-wide protests of the 1930s that led to the matanza or slaughter of over thirty-thousand people in 1932; Salvadoran women also comprised a third of the guerrilla forces that fought the government in the 1980–1992 civil war. Similar stories exist across the region.

LGBTQIA rights have expanded in recent decades in Latin America and the Caribbean, which have benefited women and people with nonconforming gender identities and sexualities; interestingly, this is accompanied by the fact there are a number of cultures in the region that allow for more than two genders, such as the machi for the Mapuche (Chile) and the muxes in southern Mexico, for example. As we’ve seen in other areas such as health care, changing legal frameworks mean that LGBTQIA individuals have more rights, at least on the books (Corrales 2015, 54). Although there are countries (Argentina, Uruguay, Brazil) as well as cities (Mexico City, Cancún, Bogotá, and Santiago) in the region where the legal framework and implementation of laws have formalized rights (Corrales 2015, 54), there are many places where rights are not guaranteed. In fact, LGBTQIA individuals—like other minority or marginalized groups—face higher levels of vulnerability if their gender identities or sexualities also intersect with other marginalized identities.

A sobering factor that affects women and people with nondominant genders throughout the Americas is violence, in general, and gender-based violence, in particular. We mention violence in general because violence perpetrated by state actors, organized crime, gangs, human trafficking, and violence against displaced and migrant people promotes an atmosphere in which gender-based violence increases (PNUD 2013, 85). In countries with a history of civil war or military dictatorships throughout the region, violence against women can be exacerbated, particularly for Indigenous or Afro-descendant women (Boesten 2010; Cosgrove and Lee 2015; Franco 2007; Hastings 2002), in part due to the failure to hold soldiers accountable for the abuse (Goett 2017, 152).

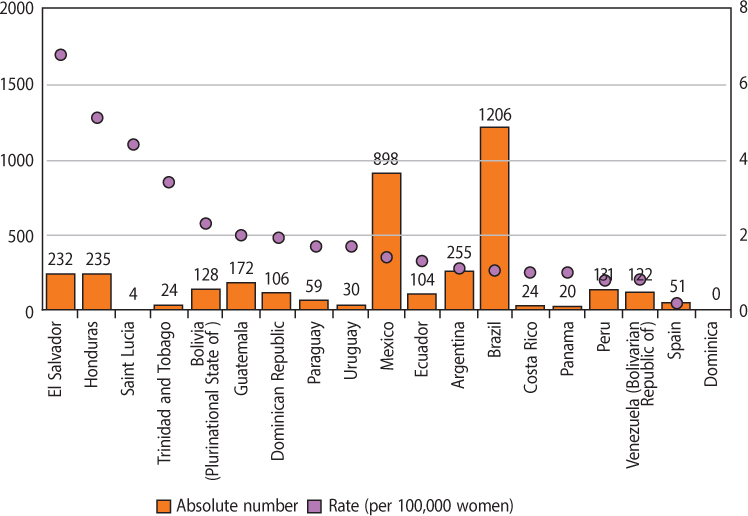

In the region, femicide rates are rising faster than homicide rates; though more men are killed in the region, the rate at which women are killed for being women is rising faster than homicide rates (PNUD 2013, 85): “Of the 20 countries with the highest rates of homicide in the world, 18 are in Latin America and the Caribbean” (PAHO 2017, 23). Almost one-third of women in Latin America and the Caribbean have been subject to violence in their own homes (PNUD 2013, 23), and two thirds have faced gender-based violence outside of their homes (PNUD 2013, 82). Though domestic and public violence cut across all social classes and other forms of difference, women and people with nondominant gender identities and sexualities often face more obstacles to gain access to justice, which is obviously worse in countries with weak governance and rule of law (PAHO 2017, 13). Though there is agreement that the region is confronting high levels of gender-based violence, it is hard to know the full extent of the problem because sometimes there is underreporting due to the fact that women and others don’t feel that their cases will result in any form of justice and/or they are afraid to report violence (PNUD 2013, 83). In some countries, the statistics are increasing, but this isn’t necessarily because there is an increase in violence against women but rather because there is an emergent culture in which members of society are more likely to report a crime.

refers to the intentional killing of females (women or girls) because of their gender.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

The arrival of European conquerors and colonizers to Latin America had disastrous effects on the entire region; the decimation of the region’s Indigenous peoples unfolded quickly as people were murdered outright or died from contracting European diseases (Denevan 1992, xvii–xxix). It is argued that in most of the Americas, Indigenous populations had declined by 89 percent by 1650 (Denevan 1992, xvii–xxix; Newson 2005, 143), a mere 150 years after contact with Europeans. In addition to European illnesses, displacement and loss of life due to slavery, war, and genocide, also contributed to the loss of life. Indeed, Indigenous populations did not recover from the conquest, and by the early 1800s Indigenous people “accounted for only 37 percent of Latin America’s total population of 21 million” (Newson 2005, 143).

When Christopher Columbus arrived in 1502 to the Caribbean coast of Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica in Central America, there was a large and thriving population comprising multiple Indigenous cultures—including the Mayas, Aztecs, Pipils, and Lencas, among others—and robust economies, including regional trade from present-day Mexico to Panama (Lovell and Lutz 1990, 127). At that time, it is estimated there was a population of 5.6 million people spread from what is present-day Chiapas in southern Mexico to Panama (Denevan 1992, xvii–xxix).

In South America, there were the Incas in the Andes, the Mapuche in present-day Chile and Argentina, and other Indigenous groups in the Amazon basin. Similar to the Aztecs in Mexico and the Maya in southern Mexico and Central America, European diseases decimated South American Indigenous peoples along with outright genocide and enslavement. It is important to note, however, that the Spanish never conquered the Mapuche, as the Mapuche warriors fought back so hard and ingeniously that they forced the Spanish to sign a treaty respecting their lands south of the Biobio River in south-central Chile. It wasn’t until after independence that the Chilean and Argentine armies finally subjugated the Mapuche in the late 1880s.

Whereas the Spanish—and to some extent the British—focused on Central America, and while in South America it was primarily the Spanish and the Portuguese, the Caribbean region had even more colonial powers vying for the region. In the Caribbean, the French, British, Spanish, and others competed for dominance; this, in turn, created obvious problems for local Indigenous populations, as was the case of the Afro-indigenous group, the Garifuna, on the island of St. Vincent. In a treaty in which the French ceded the island to the British, the Garifuna were then exiled to the coast of Honduras by the British, decimating their population: half of the Garifuna died at that time. A big development in the Caribbean—and other places in Latin America—was the introduction of enslaved Africans from the Atlantic slave trade in which twenty-one million Africans were brought to the Americas over the sixteenth, seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries. The colonization of Latin America left an imprint of inequality, elite privilege, racialized and racist institutional practices, gendered legacies, and the dispersal of Indigenous and African descendant peoples across the region. This history has served to naturalize and embed divisions between rich and poor, men and people with nondominant gender identities and sexualities, and mestizos and Indigenous peoples and Afro-descendant peoples in social mores and legal frameworks (Radcliffe 2015, 15).

These processes of enslavement, genocide, and colonization had gendered effects across the region from the beginning. Because initial population flows from Spain and other European colonial powers were primarily male with European female migration unfolding more gradually, Spanish men raped and cohabitated with Indigenous and African women leading to a new generation of mestizos or mixed-race people. The foundation of colonies was based on the rape of Indigenous women and then their expected service to this colonial project. This not only normalized violence against women but also affected gender roles between Indigenous men and women. Many historians of Latin America discuss how violence against women today is informed by the rape of women during the Conquest and early years of the colonies: this was a “broader acceptance that dated back to the colonial era of using sexual and gender-based violence to uphold patriarchy” (Carey and Torres 2010, 146), in which neither local customs nor community legal frameworks intervened to stop gender-based violence. Though there were differences across the region, colonial culture and law conspired to protect elite interests and subordinate nonelites (Socolow 1980) as well as allow local men to mistreat women as an escape valve for discrimination, poverty, and other indignities (Forster 1999). This, then, continued into the nineteenth century, or the early state-building era under independent countries, in which women were often blamed for the abuse they suffered, called witches, or categorized as sex workers and therefore undeserving of justice. This time also coincides with the neocolonial rise in global power of the United States. From the mid-nineteenth century on, US foreign policy and economic interests played a significant role in the region from supporting the overthrow of leaders critical of the United States, providing military aid to repressive governments aligned with US interests, and promoting US corporations’ expansion along the length and breadth of the region (see Chomsky 2021).

refers to people of mixed ancestry, including Indigenous and Spanish.

During times of dictatorship and authoritarian regimes in the early, mid-, and late twentieth centuries, restrictive gender roles and targeting of so-called subversive women furthered gender-based violence to the extent that Drysdale Walsh and Menjívar argue that high present levels of impunity and violence are informed by “deeply intertwined … roots in multisided violence—a potent combination of structural, symbolic, political, gender and gendered, and everyday forms of violence” (2016, 586), which moves us past the facile stereotype used to blame gender-based violence on Latin American “macho men” and instead opens up a field of study that posits colonialism, neocolonialism, poverty, state violence, and high levels of impunity as some of the causes of high levels of violence against women in the region today.

As previously mentioned, the effects of this conquest led to the emergence of a mestizo population, or ladinos as they are known in Guatemala: the children, and in turn, their descendants, of Europeans and Indigenous or African people. Some members of this hybrid group came to hold power, and upon independence in the early 1800s, an emergent mestizo elite was poised to claim power over poor mestizos, Indigenous peoples, and Afro-descendant groups. European-descendant whites and mestizos hold most of the power today in Latin America. Models of exclusion and repression were thus integrated into the early independent countries of Latin America, which continued to perpetuate exclusion for marginalized groups, including women, with the use of force and “calculated terror … an established method of control of the rural population for five centuries” (Woodward 1984, 292), which did spark Indigenous and peasant resistance, revolution, and civil war at different times.

refers to mestizos and Westernized Indigenous Latin Americans who primarily speak Spanish.

MODERN CONTEXT

The work of historians—often reading between the lines of early colonial diaries and even court proceedings—has uncovered some of the historical and cultural complexities of Indigenous cultures in the Americas and provided insight into the struggles of the marginalized and disenfranchised, substantiating claims of their activism, contributions, and struggles from the sixteenth century onward, especially in the phases of early state building after independence from Spain in the early nineteenth century. This is how a vibrant civil society emerges throughout the region with numerous examples of leadership and activism by women, workers, and Indigenous and Afro-descendant peoples (Cosgrove 2010, 43). Historically, conservative oligarchic interests and dominant Catholic Church teachings had a double standard for women. There were the elite women, bound to uphold social mores and European standards, and there were the peasant, Afro-descendent, and Indigenous women who were expected to do most of the social, economic, and unpaid domestic work during the early years of colonies and independent Latin American states.

Women often chose to participate in struggles as activists and leaders when their livelihoods, families, and customs were threatened. The actions they chose to carry out were obviously shaped by social class, race, and gender. These histories have also affected the amount of solidarity (or lack thereof) that can be found among women activists: the more stratified a society is, the more women are separated by class. Therefore, the less likely it is that cross-cutting movements will form and accomplish social change and transformation (Cosgrove 2010, 44). In Chile and Argentina, for example, it was primarily elite women who were the first to agitate for women’s rights due to their access to resources, education, and political ideas from Europe. This consciousness alienated many working-class, poor, and Indigenous women who were doubly or triply oppressed. However, in places like El Salvador, feminism did not emerge until the civil war ended in the early 1990s. Because the war had promoted solidarity among women across difference, the women’s movement emerged in the 1990s with a much more integrated and diverse constituency (Cosgrove 2010, 45). In Cuba, by contrast, women played an active role in the 1959 Revolution that overthrew the US-backed dictator Batista and brought the socialist regime of Fidel Castro to power. Socialist Cuba by no means completely eliminated gender or racial inequality, but social reforms in health care, education, and housing greatly lowered health, educational, and income disparities across the population.

Another common theme that emerges for women today across the region is the impact of authoritarian regimes on their respective populations—civil society organizers in general and women activists in particular. Most of the authoritarian regimes of Latin America and the Caribbean—the Dominican Republic, Haiti, Guatemala, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Panama, the civil war in Colombia, Brazil, Chile, Argentina, the civil conflict in Peru with the Shining Path—utilized gendered messages for women and the expectations that they would support the goals of the conservative security forces in charge of each country. Patriotic women were expected to be good mothers but not to take active roles in society or the workplace; women who stepped out of line were sanctioned, often punished, sometimes even more harshly than male subversives. Throughout Latin American history, women have assumed leadership roles in their families, communities, and even countries during periods of economic and political turmoil, which in turn has led to the expansion of opportunities for women to exercise leadership and activist roles.

Latin America and the Caribbean present interesting insights into the ambiguous or contradictory nature of policies meant to address inclusion. Many countries in Central and South America as well as in the Caribbean were forced to adopt neoliberal structural adjustment policies by international financial institutions in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. As many studies have shown, these policies had adverse effects on women and minoritized groups. Nonetheless, out of some of these policies came increased attention for Indigenous groups and their rights. Many countries were “encouraged” to implement land titling policies for Indigenous groups by the very same international agencies that had required them to cut social spending and privatize state-owned banks and electric companies. This created a space in which Indigenous peoples have made gains, but this has also meant they’ve had to negotiate these gains with state officials and the private sector: these entities had little interest in ceding land when future economic development plans include land for settlers to address the pressure of the urban poor or rural overpopulation and mega-development projects such as dams and hotels, for example. In these negotiations, Indigenous groups have found themselves having to negotiate their rights, making some progress in places and losing ground in others. This is what Hale (2005) calls neoliberal multiculturalism. Multiculturalism creates uneven gains for women, Indigenous peoples, and Afro-descendant groups (Radcliffe 2015, 22). “Uneven gains” is the perfect term because it applies to access to land and rights, but it also means doing more with less money, fewer social services, more need for women’s unpaid care work.

characterized by free-market trade, deregulation of financial markets, privatization, and limited welfare and social services for populations.

Authoritarian regimes, inequality and poverty, and weak governance and rule of law are factors that contribute to the displacement and migration of people throughout Latin America and the Caribbean today. It is estimated that half the people leaving their places of origin seeking safety or economic opportunities are women or girls (PAHO 2017, 15). Given that gender hierarchies translate as discrimination toward women and people with nondominant gender identities, risks are exacerbated when they do not have official documents for travel. The risks for these undocumented migrants of sexual violence and human trafficking are even higher when they are migrating from Central America to Mexico or the United States or from Paraguay, Bolivia, and Peru to Argentina or from Venezuela to other parts of South America.

CONCLUSIONS

Although women and people with nonbinary gender identities and sexualities in Latin America and the Caribbean have achieved improvements in health, education, and income generation, women still lag behind men in terms of political representation—though the region has higher political participation of women than the United States—equal pay for equal work, and access to formal leadership positions. Throughout the region there are impacts from macro-level policies, such as structural adjustments, and the effects of more generalized violence due to postwar or postconflict realities, weak states with low levels of rule of law, and gang violence, for example, that have even harsher effects on marginalized groups. These effects are exacerbated for Indigenous women, rural women, and people with nondominant gender identities and sexualities. These challenges, though, are balanced by a long history and a multitude of present-day examples of activism and leadership on behalf of rights, the survival of their communities, and commitment to addressing the effects of climate change. A number of international movements across different issues unite people throughout the region: this, in turn, has led to extensive transnational networks, concerted actions, and knowledge sharing throughout the region and with other parts of the world. This includes the Latin American Federation of Associations for Relatives of the Detained-Disappeared (FEDEFAM); the Network of Rural Women in Latin America and the Caribbean (Red LAC), and annual meetings of the Latin American and Caribbean Feminist Association.

The chapters in Part III Latin America present anthropological research that showcases some of the ethnic diversity and ongoing struggles for equality presented in this introduction to the region. Chapter 8 and 9 begin from the standpoint of gender being relational, that is, the experiences of women are tied to the gendered lives of men. In chapter 8 the author explores how older men with erectile dysfunction construct their identities as men in the context of a culture of “machismo” rooted in sexual prowess. The author of chapter 9 in turn, takes an intersectional view of the masculinities of Black working-class men in northeast Brazil. As a marginalized racial group facing widespread unemployment, these men struggle with dominant notions of masculinity that they cannot meet. In chapters 10 and 11, the authors examine the lives of Indigenous women and their efforts to improve the economic conditions of their families. Chapter 10 explores the unintended consequences of an antipoverty project targeting Indigenous rural women in Mexico. Here the program’s requirements help adolescent girls but hinder their mothers’ efforts to provide for their families. The author in chapter 11 demonstrates how global capitalism dovetails with traditional market practices of Indigenous women in Guatemala, as women engage in a new form of sales as independent distributors for Herbalife, a multinational corporation. Finally, the profile at the end of the introduction to the “region” section presents the work of a nonprofit focused on curbing the high rate of violence against women in Guatemala.

KEY TERMS

authoritarianism: A political doctrine that requires strict obedience to authority at the expense of personal freedom.

cisgender: refers to people whose gender identity corresponds to their sex at birth.

femicide: refers to the intentional killing of females (women or girls) because of their gender.

Indigenous: refers to people who originated in or are the earliest-known inhabitants of an area. Also known as First Peoples, First Nations, Aboriginal peoples or Native peoples.

intersectional/ality: refers to the interconnected nature of social categories such as race, class, and gender that create overlapping systems of discrimination or disadvantage. The goal of an intersectional analysis is to understand how racism, sexism, and homophobia (for example) interact to impact our identities and how we live in our society.

ladinos: refers to mestizos and Westernized Indigenous Latin Americans who primarily speak Spanish.

marianismo: a gender ideology in which certain feminine characteristics are valued above others. These include being submissive, chaste, virginal, and morally strong.

mestizos: refers to people of mixed ancestry, including Indigenous and Spanish.

neoliberal: characterized by free-market trade, deregulation of financial markets, privatization, and limited welfare and social services for populations.

RESOURCES FOR FURTHER EXPLORATION

BOOKS

- Cosgrove, Serena. 2010. Leadership from the Margins: Women and Civil Society Organizations in Argentina, Chile, and El Salvador. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- Kampwirth, Karen. 2010. Gender and Populism in Latin America: Passionate Politics. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Marino, Katherine M. 2019. Feminism for the Americas: The Making of an International Human Rights Movement. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina.

- Shayne, Julie. 2004. The Revolution Question: Feminisms in El Salvador, Chile, and Cuba. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- Stephen, Lynn. 1997. Women and Social Movements in Latin America Power from Below. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Radcliffe, Sarah. 2015. Dilemmas of Difference: Indigenous Women and the Limits of Postcolonial Development Policy. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

ARTICLES

- Burrell, J. L. and E. Moodie. 2021. “Introduction: Generations and Change in Central America.” Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology 25, no. 4 (2020): 522–31. doi-org.library.esc.edu/10.1111/jlca.12525.

DOCUMENTARIES AND FILMS

- Cabellos, Ernesto, Frigola Torrent, Núria Prieto, Antolín Sánchez, Carlos Giraldo, Jessica Steiner, Hilari Sölle, Miguel Choy-Yin, Martin Ayay, and Nélida Chilón. 2016. Hija De La Laguna—Daughter of the Lake. Lima, Peru: Guarango Cine Y Video.

- Guzmán, Patricio, Renate Sachse, Katell Djian, Emmanuelle Joly, José Miguel Miranda, Atacama Productions, Blinker Filmproduktion, Westdeutscher Rundfunk, and Cronomedia. 2010. Nostalgia De La Luz = Nostalgia for the Light. Brooklyn, NY: Icarus Films Home Video.

- Kinoy, Peter, Pamela Yates, Newton Thomas Sigel, Rigoberta Menchú, Rubén Blades, Susan Sarandon, Skylight Pictures, Production Company, Docurama, and New Video Group. 2004. When the Mountains Tremble. 20th Anniversary Special Edition. New York: Docurama.

- Montes-Bradley, E., dir. 2007. Evita. Heritage Film Project.

- Portillo, Lourdes, Olivia Crawford, Julie Mackaman, Vivien Hillgrove, Kyle Kibbe, Todd Boekelheide, Xochitl Films, and Zafra Video S.A. 2014. Señorita Extraviada—Missing Young Woman. Coyoacán, México: Zafra Video.

- Sickles, Dan, Antonio Santini, and Flavien Berger. 2015. Mala Mala. Culver City, CA: Strand Releasing.

- Suffern, R., dir. 2016. Finding Oscar. FilmRise.

- Torre, S., and V. Funari, V., dir. 2006. Maquilapolis: City of Factories. San Francisco: California Newsreel.

- Wood, Andrés, Gerardo Herrero, Mamoun Hassan et al. 2007. Machuca. Venice: Menemsha Films.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful for the support of our institutions—Seattle University and Universidad Rafael Landívar—and we are inspired daily by the example of all the women activists of Latin America and the Caribbean who are making inclusive social change happen across the region.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Boesten, Jelke. 2010. “Analyzing Rape Regimes at the Interface of War and Peace in Peru.” International Journal of Transitional Justice 4, no. 1: 110–29.

Carey, David, and M. Gabriela Torres. 2010. “PRECURSORS TO FEMICIDE: Guatemalan Women in a Vortex of Violence.” Latin American Research Review 45, no. 3: 142–164.

Chomsky, Aviva. 2021. Central America’s Forgotten History: Revolution, Violence, and the Roots of Migration. Boston: Beacon.

Corrales, Javier. 2015. “The Politics of LGBT Rights in Latin America and the Caribbean: Research Agendas.” European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies 100: 53–62.

Cosgrove, Serena. 2010. Leadership from the Margins: Women and Civil Society Organizations in Argentina, Chile, and El Salvador. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Cosgrove, Serena. 2018. “Who Will Use My Loom When I Am Gone? An Intersectional Analysis of Mapuche Women’s Progress in Twenty-First Century Chile.” In Bringing Intersectionality to Public Policy, edited by Julia Jordan-Zachery and Olena Hankivsky, 529–545. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Cosgrove, Serena, and Benjamin Curtis. 2017. Understanding Global Poverty: Causes, Capabilities, and Human Development. London: Routledge.

Cosgrove, Serena, and Kristi Lee. 2015. “Persistence and Resistance: Women’s Leadership and Ending Gender-Based Violence in Guatemala.” Seattle Journal for Social Justice 14, no. 2: 309–332.

Craske, Nikki. 2003. “Gender, Poverty, and Social Movements.” In Gender in Latin America, edited by Sylvia Chant with Nikki Craske, 46–70. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Denevan, William M., ed. 1992. The Native Population of the Americas in 1492. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Drysdale Walsh, Shannon, and Cecilia Menjívar. 2016. “Impunity and Multisided Violence in the Lives of Latin American Women: El Salvador in Comparative Perspective.” Current Sociology Monograph 64, no. 4: 586–602.

Ehlers, Tracy Bachrach. 1991. “Debunking Marianismo: Economic Vulnerability and Survival Strategies among Guatemalan Wives.” Ethnology 30, no. 1: 1–16.

Foster, C. 1999. Violent and Violated Women: Justice and Gender in Rural Guatemala, 1936–1956. Journal of Women’s History 11, no. 3: 55–77.

Franco, Jean. 2007. “Rape: A Weapon of War.” Social Text 25, no. 2: 23–37.

Goett, Jennifer. 2017. Black Autonomy: Race, Gender, and Afro-Nicaraguan Activism. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

Guthrie, Amie. 2019. “Explained: Abortion Rights in Mexico and Latin America,” New York NBC News, September 29. Accessed November 3, 2019. https://www.nbcnewyork.com/news/national-international/Explained-Abortion-Rights-Mexico-Latin-America-561721361.html.

Hale, Charles R. 2005. “Neoliberal Multiculturalism: The Remaking of Cultural Rights and Racial Discrimination in Latin America.” PoLAR: Political and Legal Anthropology Review 28, no. 1: 10–28.

Hastings, Julie A. 2002. “Silencing State-Sponsored Rape in and beyond a Transnational Guatemalan Community.” Violence against Women 8, no. 10: 1153–1181.

Lovell, W. George, and Christopher H. Lutz. 1990. “The Historical Demography of Colonial Central America.” In Yearbook (Conference of Latin Americanist Geographers) (17/18), 127–138. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Newson, Linda A. 2005. “The Demographic Impact of Colonization.” In The Cambridge Economic History of Latin America, edited by V. Bulmer-Thomas, J. Coatsworth, and R. Cortes-Conde, 143–184. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pan American Health Organization. 2017. “Health in the Americas+.” Summary: Regional Outlook and Country Profiles. Washington, DC: PAHO. https://www.paho.org/salud-en-las-americas-2017/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Print-Version-English.pdf. Accessed November 2, 2019.

PNUD (Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo). 2013. Seguridad Ciudadana con Rostro Humano: Diagnostico y Propuestas para América Latina. New York: Centro Regional de Servicios para América Latina y el Caribe. www.undp.org/content/dam/rblac/img/IDH/IDH-AL%20Informe%20completo.pdf. Accessed November 3, 2019.

Radcliffe, Sarah. 2015. Dilemmas of Difference: Indigenous Women and the Limits of Postcolonial Development Policy. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Socolow, Susan Migden. 1980. “Women and Crime: Buenos Aires, 1757–97.” Journal of Latin American Studies 12, no. 1: 39–54.

Tello Rozas, Pilar, and Carolina Floru. 2017. Women’s Political Participation in Latin America: Some Progress and Many Challenges. International IDEA. https://www.idea.int/news-media/news/women%E2%80%99s-political-participation-latin-america-some-progress-and-many-challenges.

Woodward, Ralph Lee. 1984. “The Rise and Decline of Liberalism in Central America: Historical Perspectives on the Contemporary Crisis.” Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs 26, no. 3: 291–312. doi:10.2307/165672.

World Bank. 2012. “Women’s Economic Empowerment in Latin America and the Caribbean Policy Lessons from the World Bank Gender Action Plan.” World Bank Poverty, Inequality, and Gender Group Latin America and the Caribbean Region. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/16509/761170WP0Women00Box374362B00PUBLIC0.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed November 2, 2019.

PROFILE: THE GUATEMALAN WOMEN’S GROUP: SUPPORTING SURVIVORS OF GENDER-BASED VIOLENCE

Serena Cosgrove and Ana Marina Tzul Tzul

INTRODUCTION

Inspired by the work of civil society women leaders in Guatemala, this profile focuses on the achievements and mutual support that connect the women’s organizations that belong to the Guatemalan Women’s Group (Grupo Guatemalteco de Mujeres, or GGM), an umbrella organization based in the capital Guatemala City. GGM’s mission is to support women’s organizations across the country, providing much-needed services to women survivors of gender-based violence.

HISTORY

Many argue that there are multiple historical events in Guatemala—Spanish colonization, early statehood consolidation and the emergence of political and economic elites, and the thirty-six-year civil war (1960–1996)—that contribute to today’s high levels of gender-based violence (see Carey and Torres 2010, Sanford 2008, and Nolin Hanlon and Shankar 2000). Gender-based violence is defined as “any act that results in, or is likely to result in physical, sexual, or psychological hard or suffering to women [and people with non-dominant gender identities and sexualities], including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or private life” (Russo and Pirlott 2006, 181). There are also a number of current social factors such as inequality, poverty, and discrimination due to gender and ethnicity as well as high levels of violence due to insecurity, gangs, and drug trafficking—that contribute to the “normalization” of gender-based violence in the private, domestic sphere, as well as in the public sphere.

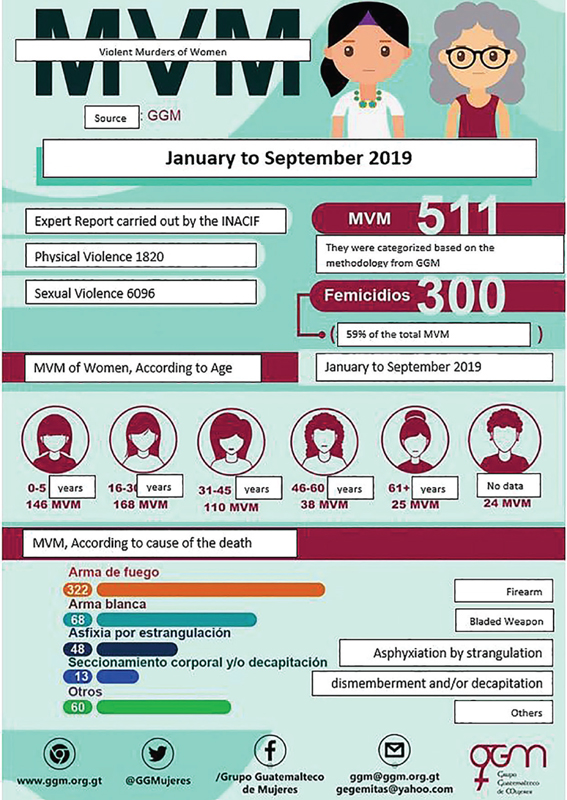

The countries with the highest femicide rates in Latin America are El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala (Gender Equality Observatory 2018). Femicide is the killing of a woman because of her gender; it is an extreme example of gender-based violence, which is on the rise according to Musalo and Bookey (2014, 107) and Cosgrove and Lee (2015, 309). From 2000 to 2019, 11,519 women were violently killed in Guatemala (GGM 2019); the rate of violent deaths of women is growing faster than homicide levels (though homicide rates remain higher than femicide rates). In 2018 alone, 661 women were killed violently in Guatemala (GGM 2019). In fact, violence against women is one of the most highly reported crimes in Guatemala, yet impunity rates are also abysmally high: only 3.46 percent of cases presented between 2008 and 2017 were resolved according to the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG, 9).

ORGANIZATIONAL HISTORY AND MISSION

The Guatemalan Women’s Group (GGM) was officially founded in 1988, and in 1991, they opened their first Center for Integrated Support for Women (or CAIMUS) in Guatemala City with the goal of providing an integrated package of services to women survivors in the capital. Today, GGM is an umbrella organization that oversees 10 CAIMUS across the country (with four new organizations coming onboard).

In its early years, GGM played a leadership role at the national level convening diverse women’s organizations across the country to assure that women’s voices were being heard in the peace process and in the early implementation of the peace accords in post–civil war Guatemala. GGM encouraged women to talk to each other from across the country, and this contributed to bridging the class divide between feminists in the capital and women committed to women’s issues from across the country. GGM also played an important role in the No Violence against Women Network, which brought together organizations around the country actively working to eradicate gender-based violence locally and to lobby for improved laws and public-sector accountability at the national level.

This activism by women led to the law against gender-based violence being passed in 1996, as well as the 2008 law against femicide and other forms of violence against women. These laws, in turn, pressured the government to form a public sector–civil society commission to promote state accountability and collaboration with women’s organizations. However, the government has never fully supported GGM or their goals. In 2018, the government only provided a small percentage of funding it had promised to the CAIMUS for their functioning. In 2019, the CAIMUS weren’t even included in the national budget, a sign that the government’s commitment to addressing gender-based violence is waning.

Today GGM provides oversight, training, and fundraising for the CAIMUS, which use the GGM model of integrated services for women survivors including social, medical, psychological, and legal services as well as access to women’s shelters. In addition to seeking resources for CAIMUS and creating a space for mutual support in a struggle that often feels overwhelming, GGM is also a think tank and advocacy organization gathering and analyzing data about the rates of violence against women and leading public campaigns to change the perceptions of Guatemalans about violence against women. Always in coordination with other organizations and social movements across the country, GGM uses key dates for women’s liberation—such as March 8, the International Women’s Day, or May 28, International Day of Action for Women’s Health, among other dates—to organize national campaigns to raise awareness about women’s rights, gender-based violence, and related issues. These campaigns use billboards and other opportunities for public outreach such as radio spots, social media, and events and programming to spread their message. See GGM’s website for more information: http://ggm.org.gt/.

LEADERSHIP

The founder and director of GGM is Giovana Lemus. Her story embodies sacrifice and commitment to women’s participation and contributions to society from before the war ended in 1996, and yet it is also about one-on-one accompaniment of women leaders. As a college student during the civil war, Giovana observed many cases of injustice and violence; she saw how these affected Indigenous people, women, and the poor across the country. In the 1980s she joined other concerned women who all banded together across different backgrounds to serve as peace builders. The importance of working with women showed Giovana how valuable it is to open space for women to support each other and their contributions. Giovana’s own childhood experiences also contributed to her activism. Her mother always welcomed survivors of gender-based violence into the home, making sure it was a safe haven for them. When Giovana’s mother died, Giovana had the example of her nine older sisters to inspire her, as well as her father who always encouraged her to speak her truth and make a difference.

Giovana sums up the important role that promoting women’s leadership can play and that women can build impact through coordinated action: “It is a concrete inspiration to carry out actions and achieve [our goals]” (Interview by author, July 2, 2013). Recently Giovana said, “Our sisterhood grows stronger because of what we’ve had to face” (Interview by author, July 30, 2019). The word that repeatedly appears in our interviews with Giovana and the directors of the CAIMUS when discussing GGM’s role is acompañar (to accompany). And even though there are so many challenges, Giovanna remains optimistic: “We are making progress” (interview by author, July 2, 2013). Giovana’s support of the directors of the CAIMUS has played a significant role in getting more CAIMUS established. The directors speak warmly of the guidance and support they have received from Giovana.

SUMMARY

Though Guatemala is often considered to be a difficult place to be a woman, it is also a country where women themselves are working together to address and transform the problem of violence by collaborating across multiple sites and levels. GGM and its member organizations often face direct government hostility, public-sector resistance in providing promised funding, and a climate in which it is increasingly difficult to raise funds for their work. This creates a double fight: the struggle to end gender-based violence and the fight for state funds to do their work. GGM remains committed to tackling both of these ongoing challenges.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful for the support of our institutions—Seattle University and Universidad Rafael Landívar—and we are inspired daily by the example of all the women activists of Latin America and the Caribbean who are making inclusive, social change happen across the region.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Carey, David, and M. Gabriela Torres. 2010. “Precursors to Femicide: Guatemalan women in a Vortex of Violence.” Latin American Research Review 45, no. 3: 142–164.

Comisión Internacional contra la Impunidad en Guatemala (CICIG). 2019. “Diálogos por el fortalecimiento de la justicia y el combate a la impunidad en Guatemala.” Report can be found on CICIG website. https://www.cicig.org/comunicados-2019-c/informe-dialogos-por-el-fortalecimiento-de-la-justicia/. Accessed August 12, 2019.

Cosgrove, Serena, and Kristi Lee. 2015. “Persistence and Resistance: Women’s Leadership and Ending Gender-Based Violence in Guatemala.” Seattle Journal for Social Justice 14, no. 2: 309–332.

Gender Equality Observatory for Latin America and the Caribbean. 2018. “Femicide, the Most Extreme Expression of Violence against Women.” Oig.cepal (website). https://oig.cepal.org/sites/default/files/nota_27_eng.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2019.

Grupo Guatemalteco de Mujeres (GGM). 2019. “Datos estadísticos: Muertes Violentas de Mujeres-MVM y República de Guatemala ACTUALIZADO (20/05/19).” GGM (website). http://ggm.org.gt/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Datos-Estad%C3%ADsticos-MVM-ACTUALIZADO-20-DE-MAYO-DE-2019.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2019.

Musalo, Karen, and Blaine Bookey. 2014. “Crimes without Punishment: An Update on Violence against Women and Impunity in Guatemala.” Social Justice 40, no. 4: 106–117.

Nolin Hanlon, Catherine, and Finola Shankar. 2000. “Gendered Spaces of Terror and Assault: The Testimonio of REMHI and the Commission for Historical Clarification in Guatemala.” Gender, Place & Culture 7, no. 3: 265–286.

Russo, Nancy Felipe, and Angela Pirlott, A. 2006. “Gender-based Violence: Concepts, Methods, and Findings.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1087: 178–205.

Sanford, Victoria. 2008. “From Genocide to Feminicide: Impunity and Human Rights in Twenty-First Century Guatemala.” Journal of Human Rights 7: 104–122.