4.1: Sinews Torn and Sinews Strong- Stories from Three Generations

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 150144

- Brenda Anderson, Shauneen Pete, Wendee Kubik, and Mary Rucklos-Hampton

- University of Regina

Tracey George Heese (B.Ed.) and Carrie Bourassa (PhD)[1]

okâwîmâ. At the breast of women, the generations are nourished. From the

bodies of women flow the relationships of those generations, both to society

and to the natural world. In this way, our ancestors said, the earth is our mother.

In this way, we as women are the earth (Cook 156).

You will never understand unless you slip my moccasins on. I wanted a life that is mine, creating my own path. In the wrong place in the wrong time with the wrong person. My spirit helpers could not save this flesh. See the historical behavior of the colonial legacy. Is the victim at fault? Was she brutalized with a furious rage, her own fault? It is difficult to hear the stories and have to step back and look at the big picture as “Coroner” to examine how so many of our women are disposable. Thank you to all those families, communities and individuals who share their experiences. Hearing about the blindness of individuals who can SEE the evidence of the Regina City rallies for the families with missing and murdered loved ones, rallies around the murders of our women here in our own PILE OF BONES[2].

Maybe had I done my homework, had I put my heart on the shelf, had I not felt desperate or had been content with what I had. Maybe I could have protected myself, could have shielded myself from my death. Now, wrapped in my mother’s shawl, telling myself if I could protect you from a broken heart, if I could wipe away the tears, if I could take away all your pain, I would. Now a dream dressed in quilled moccasins lifted and wrapped in a warm hide to return to the weaving of the stars.

Winnifred was murdered in Edmonton, Alberta on May 7, 1991 at the age of forty-two. This chapter examines the colonial contexts that have created the stigma, racism, and discrimination facing Indigenous women today by using an Indigenous storytelling methodology. We share Winnifred’s powerful story to reveal systemic discrimination and institutional racism and explore how her daughter Tracey has been able to heal and become an important role model for others who are grieving the loss of our missing and murdered Indigenous women in Canada.

Sinew for Life, Belly Button Teachings

And this story inside of me has to do with sewing my own book in telling glimpses of my life, my mother’s life, and my grandmother’s life story—our sinew for life —connects us to my daughter and to our granddaughters yet to come. You need to know where you come from. Put your hand on your mid-stomach. There is a sinew that connects you to your hereditary blood to the dressmaker of the universe . . . that rope keeps you connected to the Creator and to your mother. When you first come into this natural world, that cord is tied with a knot to prevent you from falling into the unknown. Your mother’s cord is connected to your grandmother and your grandmother’s cord is connected to your great grandmother all they way back to the beginning of time when the first woman fell onto the turtle’s back. This is the very beginning of the sinew teachings of life.

Long before the Canadian government’s apology and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, my grandparents were rich in many, many ways. We lived from the land and I loved my grandparents very much. But at the age of eight, I was taken into the care of the Saskatchewan foster system during the period presently known as the Sixties Scoop, the Indian adoption project. It was horribly inhumane for my grandmother to have experienced first her children being taken by the Church and RCMP, and then her grandchildren being taken by Saskatchewan’s social services system, all mandated by the Canadian government.

My grandmother did what she had to do. My mother did what she had to do. And, in my life, I did what I had to do. The common thread of sinew in three generations is my grandmother who was seriously encouraged to marry my grandfather because he was considered wealthy and would make a good protector and provider. My grandmother said she was too young to be married and had no interest in starting a family. She thought herself as just a little girl. What would she know about having a family? There were still so many things in life to learn, but her older brother brought both his sisters to grandfather, who chose my grandmothers as his wife. I’m not sure what my grandfather paid to have this arranged marriage, but I do know that my grandmother did not want it. The common thread of sinew is that a woman’s life is worth next to nothing in Canada.

My mother’s life: she was taken from my grandmother by the red coats and sent off to Round Lake residential school. Did my grandmother believe she was being punished for having children? All of her children were swept away by the red coats. Did she even want these children, this life she was forced to live? The sinew between my grandmother and her children was forcibly severed.

My mother Winnie learned to take the beatings from the nuns and sexual abuse from the black robe. She was the oldest of her siblings that attended the school. Her father, my grandfather, hid her older brother in the bush to protect him. At school, my mother was forced into a life that she certainly did not want in carrying the male role of protecting her little brothers and sister. She was strong, undeniably loud, and spoke up. Yes, she was strapped daily, chained, and jailed often. Yes, she was treated as a wild savage, but that unimaginable childhood would serve her as she bloomed into a young woman. Most of our men and women are born to fill the jail system, social services system and, with the odds of diabetes or suicide, likely the health care system. Yes, our babies will give you jobs and make you rich and fat. Your funeral homes and hospitals will profit from the birth and death of our babies, the death of our women, and the death of our people. Many have gotten rich from our mortality.

Violence against women is about power and control over her life and her body (Amnesty, 5). We are First Nations, but we never call ourselves that. We call ourselves “Indian,” not the kind that wears a sari but the kind that wears moccasins. My mother was a part of the generation of children that was hauled off to residential school, and then she grew up to be hauled seasonally in and out of jail.

My mother may have learned how to cook, clean, sew, tend a garden, and speak English at that school. But she had to endure sexual, physical, mental, and spiritual abuse at the will of the minister and nuns ordained by a church and sanctioned by the government to run the Round Lake Residential School.

My grandparents’ never taught my mom to speak Cree, probably to protect me or to decrease the beatings at Round Lake. One good thing about the school is that it was where my mom met my dad, and soon she was free of the Round Lake prison. Both she and her handsome warrior from Pasqua took off to the big city with no money but enough love to change the world. Very soon after, they both knew she was carrying his child.

My mom loved my dad but he made a drunken choice and shot his brother. He was sent to high security lock-up for sixteen or eighteen years for manslaughter. Not the fairy tale that anyone could hope for. Winnie was destined to do it on her own. Being thrown away, she was left to mourn her dream of a happy ending.

My mom went back home to her parents, helped her dad with cutting pickets, really man’s work but even being pregnant did not stop her from doing what needed to be done to survive. With the little money she earned, my mom took a bus up to the Prince Albert jail to see my dad. Something happened to my dad in jail. He pushed my mom away. My dad told my mom to forget about him, that he wasn’t worth it. My mom gave birth to a baby, and she was a girl . . . How? How? How can I be a mother? She checked herself out and left that little girl at the hospital. I was that baby girl and my grandmother claimed me. Winnifred was never able to reconnect to the belly button teachings. She lost the strength of her grandmother’s teachings. The sinew had been cut.

After mom left me, she worked on the streets. Every individual makes choices and research says that you know right from wrong at the age of eight. The Church says, “Give us your children till at least the age of six, and they will be ours for life.”

The Canadian government, Indian agents, and Indian commissioners treated and viewed Indian people /Aboriginal people and Indian women /Aboriginal women as less than human, as merely a way to make their riches from and off of. There are many examples of government officials

debauching Indian women. As proof, Cameron assured the House that he knew of an Indian agent who lived on a western reserve “beneath the shadow of the Methodist mission, in open adultery with two young squaws.” He also cited the case of an Englishman who, although unfit for public service in his country, had been appointed to Indian Services in the Territories where he had been “revelling in the sensual enjoyment of a western harem, plentifully supplied with select cullings from the western prairie flowers. (Cameron, quoted in Barron, 139)

Even though we may have gained the vote in Canada in 1960, we were still yet to be viewed as human in Canadian society.

But it wasn’t only government officials that abused Indigenous women. Even our own men did it. The following story was shared with me by one of Winnie’s closest friends, an Aunty of mine. My mom was chumming with her friends. They always had a great time. They did lots of crazy stuff. This one time one of her girlfriends stood at the corner to get a “John” to get a room for an unspoken party of passion. She said, “You got anything for us to drink, some Baby Duck or whiskey? And, we will get our party started.” As soon as her friend was in the room with this guy, Winnie followed and waited five minutes before banging on the door. She pushed her way in and told him to get the hell out. This “John” was a married chief and had no business trying to have a sex-date with anyone except his wife. Well, this chief, just in his white boxers standing in the hotel hallway, begged to be let back into his room. Winnie tossed his clothes out and said, “You better get out of here or I will call your wife.” He left, unable to call the police for help and unable to explain how the events came to be without incriminating himself. All of my mom’s girlfriends showed up and they partied. Life was good. They partied till the next morning. The chief showed back up begging at the door to be let in. He said, “Look under the mattress. There is five thousand dollars cash. It’s the band’s money. Please! Please! Can I get it back?” So, Winnie checked and holy shit! There was a bag of cash stashed under that queen-sized bed, but they were too drunk to be woken by the lumpy mattress. Winnie took pity on the idiot and gave him the bag of cash. He broke down crying, just so happy he got the cash back. Well, he gave my mom fifty bucks and took the room of girls for breakfast, and they all partied another night together.

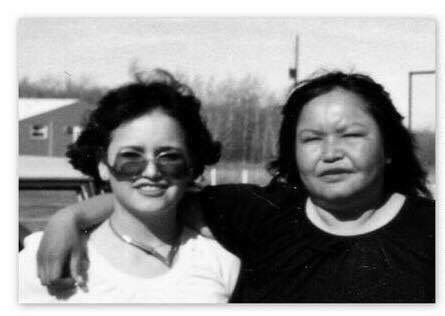

I am my mother’s daughter (Figure 1). I am proud to be a pagan squaw. I am her. She is me. The sinew between us is too strong to break forever. She carried me with the feelings of being shunned or shooed away. Did my mother carry my grandmother’s sins or was she paying for all the shame endured at the residential school? All of my grandparents’ children were stolen by the red coats and jailed in residential school. Two of my deceased uncles became sexual abusers. They learned that behaviour from that school. Did all of my aunts and uncles have to suffer because my grandparents did not know how to fight the government or fight the Church or fight the red coats? Or, was my mom destined to pay for that Treaty Four agreement between the Queen and our Red Indians.

Figure 1. Winnifred George

DO SOMETHING . . . I went to Edmonton with hopes of finding where my mother was last seen. Instead, there are many more questions that arose. Was she assaulted before her violent death? She is not “counted” as one of the murdered or missing. I was told that if she was found in Edmonton or the surrounding area that she would have been brought to the hospital whether she was injured or deceased and that it was up to the coroner to decide if it was homicide. How is it possible that our WOMEN can have their skulls crushed in and for it not to be considered homicide? When our Canadian society says nothing or does nothing, we all lose. WE ALL LOSE our “Human-Ness.”

Winnifred George April 8, 1949 – May 7, 1991 (May 31, 1995 is what I believed, but it was incorrect according to the medical examiner). I believe my mother was murdered in a downtown park in Edmonton, Alberta. In her forty-two years, she made many friends in her gypsy-street lifestyle from Vancouver to Winnipeg to Saskatoon to Regina, including Calgary and Edmonton. She had three daughters. As a mother, she did the best she could with what she knew at that time. Many have shared with me that she loved her three girls and missed us. Forgive me Grandmother and Grandfather Spirit Helpers for taking so long to be requesting answers to her blood calling out . . . forgive me for blaming her, the victim, in her death . . . forgive me for feeling shame. Asking the Creator Great Spirit to take pity on our families that are suffering when loved ones go missing and murdered—condolences #MMIW.

I am homesick for heaven and am tired of this hell on earth. This pain is too great for me to carry. The devilish spirit relishes in pleasure over my painful sorrow. My cries are ridiculed and danced to. Every human that has ever walked this earth is destined to endure heartbreak, to have sorrow and obstacles to overcome. This is all normal and natural. The heartless spirits attack, telling you, “You are disposable. It’s your own fault. You shouldn’t have worn that outfit. You’re stupid. You asked for it. Nobody will ever love you. You don’t matter!” Just kill me. God please smash me up so I will forget. Give me amnesia. Let me suffer out my breath as a brainless vegetable. I don’t want to care anymore. Please take this pain. The suffering is too long. Forgive me. Yes, I chose this life. I made choices. It is my own fault. Just give me another drink to dull the pain. “Cheers to my death.” This downward spiral to finally sleep, to never wake up crying, forever to be lost in hell on earth. Pastahowin, karma, have I paid this brokenness forward to my daughter or to my granddaughters? Our family cycle continues to let those moniya, wasi’chu say, “Look! They are killing themselves.” Those blind wasi’chu living off of the fat of our mother’s milk. Just suck her dry. Kill her. Let her go missing, and you’ll damn yourself.

Pastahowi when you go against nature or the right way to act and you know it’s wrong and it might come back to you in a bad way later. It’s a teaching but never one of revenge. It’s a teaching that all we do may have consequences for us later in life to ourselves or others we care for. So we should be kind and act with kindness to others. Sometimes people say others who wronged them may have pastahowin but that’s not a good way to think. Even karma is not punishment in eastern philosophy. It’s more about the guilt and suffering you bear when you have purposefully done wrong and that you must live life knowing it.” (Wheaton,

Facebook entry)

Scooped

Note and understand that my experience is only one from the adoption project during the Canadian Sixties Scoop. “The white social worker, following on the heels of the missionary, the priest, and the Indian agent, was convinced that the only hope for the salvation of the Indian people lay in the removal of their children (Fournier and Crey, quoted in Sinclair, 67).

A blue Ford drove onto Ochapowace to my grandparents’ home. A white woman arrived while my grandmother was in the hospital due to a stroke and my grandfather was out snaring rabbits for supper. Us three little girls were outside playing when the lady asked us, “Would you like to come for a ride?” Now, car rides were rare for us little Indian girls and I said, “YES!” with excitement. Being only eight at the time, not understanding or knowing the scope of what this ride meant or what it would cost, we three girls took that car ride and were put into foster care for four years—which meant the end of innocence, the love of childhood memories, and being directly cherished by my grandparents.

We were put up for adoption and an ad was placed in a newspaper. Through the protection of our Creator, we three girls were eventually blessed to be found by the Heese family. Soon after we were adopted, we also found our original family: my grandparents, aunties, uncles, cousins, and the rest of our natural extended family. In respect and love, I claim both names—George and Heese.

Before we were adopted, my childhood stories are similar to many others who understand a child’s misery. I was choked to silence and beaten: “Speak no lies! Tell no truth!” But in terror, I have consciously and unconsciously reviled the shame that my kin gifted. As a powerless child being called a “tale tail,” a liar, or troublemaker because I tried to get help. I was beaten and pushed down into the dirt basement to prevent me from telling the event of witnessing my Auntie’s rape. Yes, I became the systolic doll silenced. The abuse that was endured came from family and from both men and women, from the families we were forced to live with. We were forced beyond our will to choose where we would live. We were forced to live in poverty. The government since the time of the Indian agent and farm instructor wanted to gain control over the Indians—control over the food rations, annuity money, and the pass system. The Aboriginal Women’s Action Network reports that “80 percent of Aboriginal women surveyed were victims of family violence, sexual assault, and abuse from attending police.”

As a young child of five or six living in Saskatoon, my friend and I had a grand plan of going swimming down at the big pool. We were only allowed to swim there if there were grown-ups with us. On this special day, my friend said for me to wear her bikini while she wore her one piece. I believed that she came from a wealthy family because she had two swimsuits while I didn’t even have one. We went down to the water park to play until her aunty was ready to go over to the big pool. There was a bunch of us kids playing in the water when her aunty showed up. Her aunty was mad that I was wearing this bikini yelling, “That is not yours. You’re too fat to wear that, you thief!” She then yelled at my friend, “I bought that bathing suit for you. She will stink up your suit. Get it back right now.” And, before you know it, I had this grown woman grabbing my ponytail and holding my arms as my friend and her cousins tore the suit from my flesh. There I stood, all scratched up and crying, with my friend and the others laughing. Through blurred vision, I attempted to cover up, hearing them sing, “Fatty! Fatty! Na! Na! Na! Fatty! Fatty! Na! Na! Na! Fatty! Fatty!” That brought out the rabid dogs all foaming at the mouth. Seeing their naked prey, yes, these boys chased me, throwing rocks and dirty names at me. My saving grace was an elderly grandma that came to my rescue with a straw broom and scared them boys away. She gave me clothes and got me to safety. I never told anyone my horrible experience of child’s play until now.

In foster care, witnessing a young girl, a teen, being handcuffed to the bed for she too was in care: it was months of having to listen to her cries, her pleas to be free of her confinement. She may have been fourteen or fifteen years old and not allowed to leave her bed because as soon as the foster father or mother unlocked those cuffs, the young girl fled. This one time she was just in a tank top and panty-style shorts when she was up the flight of stairs from the basement and out the front door in the middle of the winter. She did not want to be there, but social services or her social worker jailed her along with the police’s help in the same home I was put in. I wanted and wished I could help her, but what could I do? I certainly was stuck there too. This was the first home I can remember. This was the family that used lighter fluid to kill the lice in our hair. They also burned my favourite pair of baby blue cords and sent away my fluffy kitten. I wished all the time that I, too, could just run away and take my two younger sisters with me to go find our grandmother.

How can people be so cruel to the helpless, to the young? Where did people learn this? Where did they learn to treat others? Did they go to that school at Round Lake? Had the black robes done this to them? Did they learn this behaviour in Rome or France or from England? Had they learned to hate so much that they no longer saw themselves in others during the violations of being beaten, raped, caged and tortured? You will never understand unless you examine historical behavior of the colonial legacy, which says that the victim is at fault for how they are treated. “Repeated invasions of the child’s territory and body space reinforce his or her self perception as a victim, and an inability to avoid further victimization, be it sexual social or economic.” (Bagley and King, 116)

But some of the sinew between my grandmother and me survived. My grandmother was a soft-spoken woman with the authority to allow me to feel like I was her favourite. Her hands were mostly busy sewing moccasins and beading for an Indian trading post in Saskatoon. I clearly remember she would sew sixty pairs in two weeks. This one time, she only had thirty-five cents to deliver them downtown so she sent me. I was maybe five or six years old and, yes, I delivered them sixty moccasins. Then I returned home, and we went off to eat coconut cream pie in a Chinese restaurant, the one place that welcomed Indians. With a mirrored backsplash to showcase them delicious pies, we sat at counter seats that were chrome vinyl stools. Still today I have echoes of my late Kokum speaking softly, helping me to mend and love my Spirit.

As a shy little girl hanging on my grandma’s dress hem, I was attached to my grandma with that strong sinew that connects us to our mothers, grandmothers, and the Creator. I went everywhere with her. I loved her. She would sit to bead leather vamps and would have me string beads to make loose beads into hanks or necklaces. I would sort out bead colours, just happy to be given this role as her helper. Yes, I have many fond memories of learning from my grandmother. I can’t really remember how old I was when I was shocked to learn that Winnie was my mom only because I had always thought my grandma was my mom. Now, today, I can’t help but think of one of my own son’s books, “Are you my mommy?” Kim Anderson says, “One of the most important teachings shared between grandparents and their grandchildren was the principle of reciprocity in relationships. Youngsters were not simply passive recipients of care and teachings. They were often helpers to their grandparents and were given tasks and responsibilities that facilitated their learning” (Anderson, 73).

Gertie Beaucage of the Ojibway of Nipissing First Nation in Ontario shared her experience of her grandmother tanning hides. “When the hair is all off and all the fleshy parts are all off and it’s nice and clean and it has been doing this soaking business for a while, then you have to take the water out of the hide, and you have to stretch it. Well, there’s nothing more perfect than five little kids, all stretching this hide that she was preparing! (Anderson, 73).

Remembering my home with my grandma when my mom would visit. This one time, my mom had a black satin lace slip and feather boa. I thought and said when asked, “What do you want to be when you grow up?” I thought and said, “A hooker.” I had no idea what the word meant but that’s what my mom was, and I wanted to grow up to be my mom because, in my eyes, she was smart, beautiful, and strong. She had the best laugh and the greatest sense of humour. Others were drawn to her. She was magnetic and fun. But, eventually, I was taught to be ashamed of her, to be ashamed of myself, and to be ashamed of all my relations.

Nobody asks to be discarded. How can I love my grandmother when she gave birth to a son who learned and became a pedophile that sexually abused her granddaughters? With so much anger, rage, and hatred, my mother attempted to kill her brother. It took five strong, grown men to hold her down so my broken uncle could escape death. Why did they let him live? Maybe my mother taking revenge would have scarred her, she would have had to dig her own grave, or it may have been considered cowardly. Regardless, I’m forever grateful because my mother believed me and was willing to protect me; for my mother at least stood up in protection of me as a little girl. I will forever love my mothers. God forgive my family. Forgive all my relations.

Is God relishing in human pain, greed for the milk, and lusting after her breasts to graze his livestock? The Creator must be blind. Does the Creator care that I am just another disposable Indian woman? Why did my parents have sex? Why did my grandparents give my mother life? The slash marks on my arms are evidence that life has been severely difficult to live. You think you know me. It may be hard for you to imagine what it takes to want to end the pain. I’m not looking for your pity and, no, I’m not trying to control you. You are wrong! All those that judge my pain may your superiority rape you and rip you and your family to pieces. Understand that I wish you no harm, no pain. I just know no other way to numb “the letting go.” Yes, I was born into a messed up history. I don’t blame my parents nor do I blame my grandparents. Those government policy makers are accountable for my messed-up history. But, please understand why the wolf chews his leg off to escape. Understand why the buffalo stands in front of Van Horne, Sir William forced to offer up her life so you will live. Bury me in this pile of bones so I will turn to dust. Please don’t send my bones to England or China to be made into teacups. Then my spirit will be freed to leave this hell here on earth. I will have escaped to be returned to my right place in the happy hunting grounds.

I was separated from my birth family and community and moved to and from several foster homes. Having to survive those traumatic years of abuse and separation ended at the age of twelve. My two younger sisters and I were adopted by a German Mennonite family who loved and cared for us as their own. My adoptive parents reconnected us with our birth family. I’m forever grateful and love my parents and German family. They helped me while I struggled with identity, battled depression, and searched for a place to belong as a survivor of the Sixties Scoop and the residential school legacy.

As a teen, I wanted to be white, blond, and blue eyed, wanting to hide my heritage because I was ashamed of who I was and where I came from. Yes! Yes! I bleached my hair, which then turned green and then orange in the summer chlorine swimming pools. Ha! Ha! Ha! Ahh! I even had coloured contacts in an attempt to change my Indianness. I learned, or was taught, from the time I was exposed to the extended community from name calling like f’n‘ squaw, wild savage, Pocahontas, and apple to name a few. Then, learning in school and on TV of drunken Indians and Indian givers. All of these stereotypes are negative and damaging to my spirit. Dealing with this information, I needed other women to be my teachers and role models and am grateful to each one of them as they have helped me to learn my history, where I come from, and how to cope with the effects of being an Indian woman. My teachers have also encouraged me to teach and share the knowledge of warrior shirts and the strength of the shawl. In university, I learned about the Sacred White Buffalo Calf Woman and how she came to help people. I also learned about our creation beginnings, the teaching of Sky Woman being powerful and with a great responsibility for our people to create and nurture. All human beings are first born in the womb of the mother. There are many versions of the White Buffalo Calf Woman but the heart of her teachings hold “generosity, humility, honesty, and respect for all things in creation” (St. Pierre and Soldier, 38–41).

A Shift in Perspective

Now, as a grown woman raising my own children, each of my sons and daughter are a blessing. I am grateful to be their mom. It is only in the last ten years that I have become aware that I have raised my children with the fear they too would be taken with me having being taken and also because statistically I, as an Aboriginal mother who was a single parent and a high-school dropout when I had my first son, was under scrutiny. But the sinew between us has not been broken. It continues to connect us to each other, to my mother, to my grandmother. With the help of my parents and my older sister as my support group, I was able to return to school to get my GED then go on to university to become a teacher.

My children are my life, and the work that I do and have done is with the prayer that they will have opportunities to be productive members of the community and family. School has been a struggle for each of my children just as it was for my grandmother, my mother, and me. In truth, it was at the Saskatchewan Indian Federated College (SIFC) where I had my very first Aboriginal, Native, and First Nations teachers. Attending this school was a blessing for me. It was a space to reconnect and build my knowledge of Canadian history.

I learned how to piece together the stories of the Treaty Four medal, the Indian Act, and the Indian agent during the pass system era and residential schools, eras that my grandfather told me about. From 1871 to 1930, our lands were secured for the railway and highways to transport goods across the country via the Treaties. Our landscapes were altered for profit, greed, gold, diamonds, uranium, lead, coal, and oil. Digging up our Mother’s resources comes with a human life price tag. Also, clear cutting our forest and contaminating our sacred water sources all comes with a plant, animal, and human life price tag. All of this has carried on for more than a hundred years and, when we stand up in protection of our home lands, our women, or our water, we are considered the “savage Indians,” or it is said that, “The Indians are getting restless.” I challenge the government and the CEOs of corporations to give up food and water for “Lent” for four days and four nights and then consider your own human price tag. Drink from the contaminated water, eat the lead poisoned caribou or fish, and then consider your own human life price tag.

“The code of silence . . . consists of documents dating back to the Doctrine of Discovery. The Doctrine of Discovery was used by the colonial powers of England, Spain, Portugal and France to divide the ‘new world’ they were discovering. Following the Doctrine of Discovery, came the 1830 Detribalization policies of the same colonial powers. Sanderson said these two documents led to the issuing of a Papal Bull by a Pope in the 14th century. The issue gave colonizers the ability to carry out actions as if it were ‘God’s Will.’ The Papal Bull said Indigenous people are not human or Christian. Because Indigenous people are not human, they don’t have sovereignty in government; they don’t have title to land and resources.” (Sanderson, quoted in Eneas)

In healing my spirit, I have sought out Elders, Pipe Carriers, and grandparents and gone to the lodges in prayer and sacrifice. I went because I was lost in my own pitifulness and needed to heal the spirit of the child within me. All of these gathering of family and community have grounded and strengthened my connection to the land. Returning to Ka-Ki-shiwew Ochapowace, Sakimay, Pasqua, and Piapot lands has allowed me to find my family and myself. In my spiritual journey, I also had the interesting privilege of participating in the Nimis Kahpimotate (Sister Journey Canoe Trip) hosted by the Lutheran Church in 2014. It was a 45-kilometre canoe trip up to Grandmother’s Bay. Seven of the thirteen participants were church members who wanted to understand the residential school experience and become part of the reconciliation of the wrong doings. In preparing for the trip, I brought my tithings of tobacco, prayer flags, and a gift to family Elders to ask for prayers for protection of my children while I would be away. Off I went into the wildness with twelve other women whom I had never met and with little-to-no experience canoeing. I was grateful to be part of this circle. Along the way, I kept finding wild strawberries. When I returned home, my Aunty explained that the moccasins she had gifted me for this journey were heart medicine. Her prayer for me was that my heart would be healed or made whole again. That is really what reconciliation means to me.

One is no greater than another. Your life is no more valuable than our seventeen hundred missing and murdered women. Acknowledge that we are all part of the human race. Many people, me included, submitted beaded flower vamps for WWOS for family and community coming together (Figure 2). When I began needing a connection or connecting back to my mother, I needed to know why she was murdered. I wanted to know her life story so that I could learn my life story. I am still learning to be here in this world, moving through the sewing skills of my mother and my grandmother.

Figure 2. Walking with Our Sisters poster.

I believe that my late mother Winnifred George was murdered. Who would care if I went missing? I am raising my adopted granddaughter as my daughter. If anything were to happen to her, would others care? The Canadian message is clear: our seventeen hundred murdered and missing Aboriginal women are just hiding or are hidden. In working with the other women of Walking with Our Sisters, I thought every inch of the red path in the university art gallery was to showcase and encourage all people to stop and think about how behind each moccasin vamp is a woman who was stolen, vanished, or murdered. STOP to think! You have daughters! You have sisters! Acknowledge that we are human!

Who is God? Who is the Trickster? The crow flies from point A to point B in search of the dead following on the coattails of Mr. or Mrs. Reaper. How thankful you will be in the wrong place at the wrong time for the crow to feast. Is that where the Trickster comes in with a wise Bugs Bunny companion? The Trickster lives to join me in a tripping dance over the roots of my mother’s dream, dressed to re-create myself. The murdered and missing in Canada are the fabric of Canada. I cannot understand how our society can turn a blind eye to a lost life, a lost IDENTITY. It’s disheartening how society can look at another with an attitude of superiority. This began with Canada’s birth.

Because I was sexually abused as a small child, I learned to be the world’s greatest secret keeper. In the moment that my little niece of six years old tells me, “Ooh! I go there by myself, but it’s a secret. Don’t tell my dad.” My stomach turned as an instinctual cautioning signal calling out, “Danger! Danger!” And, as we walked down the road, we spoke of never keeping secrets from our mom or our dad because our moms and dads keep us safe. If I went walking all by myself, I could get lost or some big animal could come take me away. We must always tell our mamas and our papas. And, just as we were about home, a long garter snake caught my eye in the grass. I pointed it out to my little niece even though I had been taught to be scared of them. I didn’t need to teach past learned fears forward. When I was a little girl, I learned the game of secrets and now I know that I need to tell my mama and papa and grandma and grandpa of the hidden shames. Please allow me to share my concern. Maybe this is nothing but I am only bringing attention to learning about “secrets.” I don’t wish to tell my own children of the shames I carry as a sexually abused little girl. I don’t wish to tell my own children about the physically abused little girl. But, I will tell you how grateful I am for my mom believing me when I told her what her brother did to me. It started innocently. I loved my uncle. He brought me presents and candy and visited me in the hospital. As a little girl, how did I know that an innocent gift of candy and tickling would lead to great pain and suffering? Thank you for listening and believing the damage of a secret.

The games we play as children: we love to have fun, laugh, sing, and play but the “whole” is balanced by hatred, sadness, crying, pain, suffering, and the loss of childhood innocence. It’s okay to be emotionally vulnerable. It is time for me to detach. There have been and are moments when I was protected from beyond the heavens. Maybe my mother, grandmothers, or one of my protectors has prevented me from being completely destroyed. Thank you! Thank you for all that I am! Having to navigate a lower life expectancy, housing shortages, a lower income, unemployment, high poverty, depression, and family violence has oppressed the health of Aboriginal women. In Canada, 70 percent of all deaths before the age of seventy-five are avoidable mortality. First Nations members were at higher risk of dying prematurely and from avoidable causes, compared with their Aboriginal counterparts. The disparity was particularly evident among women and younger age groups (Statistics Canada, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-003-x/2015008/article/14216-eng.htm).

In the beginning, women, woman carry the sphere of life. If a man understands you, he will protect. He will value and protect his sister, mother, grandmother, and daughter. He will value and protect what it means to hold the spirit of woman. She has magic and she has a direct connection to the Creator and has all authority to create. She is a woman. As women, ee go to other women to nourish each other. We go to them when we’re hungry. We go to them because they wrap us in their arms and listen. Woman is a mother. Woman for her first BIRTH. Thank you. Sing, dance, celebrate to burst into my life, tears of joy, of exhaustion, of pain, and trusting. Mother, she can correct the numerous sadnesses and the shame. Woman is life.

Blood of Our Mothers

Mark (name changed for privacy) became handsome in my vision as he searched for his chance to get my attention. He was charming, funny, and very clever. We began to spend time together in drama class. Yes, he was a senior and I was a junior, very much enamored by his humour and thrilled by his desire to steal me away from others. We would attend youth groups and go for coffee. How we would laugh. The stories he would tell. Yes, I was in complete awe of this boy who was almost a man. Love’s first kiss would scar us both for life. Yes, Christian’s parents planned and financially paid for our “happy un-birthday.” Mrs. Bell spoke directly to me as a filthy whore and certainly wanted to protect their reputation in the community. Yes, descendants of the Scottish community did not want a grandchild to forever connect them to a dirty squaw Indian. It was certainly his older sister’s health card that carried the abortion.

Yes, both Christian and I struggled to carry the burden of our choices. He ended up on the fourth floor of the psychiatric ward because he attempted suicide and was brought in on two separate occasions: once to have his stomach pumped and once for attempting to hang himself. It was repulsively pathetic to look at his face or to be in the same space as him. It was also painful to have his mother blame me for all of it, for her saintly son deserved greater than someone of my nature. Why had I not run or phoned my parents? Why had I taken the “easy way out” that led both of us to the room of suicide as our child was sucked from my womb. Our love became our nightmare. I did the unforgivable. I killed my child that grew within me. As I could not carry the shame, the only relief was to spill my own blood. Slashes are forever reminders of my shame. But this didn’t start with Christian and his parents. It is the legacy of Canada’s genocidal policies.

This thing called life, life in Canada, born as an Indian woman. My hereditary blood, my blood, is also my strength. I’m made of the blood of this land, a custodian of our great lands. Blood of our mothers, of the first woman, and our blood has given us the resilience to survive the last 250 years of Canada’s constitution, policies, laws, acts, Indian Affairs, Indian agents, and the Indian commissioners that administrated and controlled Indian, Indigenous, and Aboriginal people. From King George III’s Royal Proclamation of 1763 to the Crown’s acquisition of Indian lands; the 1857 Gradual Civilization Act introduced by Etienne Paschal-Tache and John A. MacDonald; the 1876 Indian Act passed by Parliament; and the 1885 North-West Rebellion, which was a result of mistreatment by Indian agents, communities were starved. Then, to control the Indians, the pass system was introduced. Assistant Commissioner of Indian Affairs Hayter Reed proposed the pass system in the “Memorandum on the Future Management of Indians,” which was approved by Commissioner of Indian Affairs Edgar Dewdney and MacDonald who was then Prime Minister of Canada. The provinces gained jurisdiction over Indigenous children under section 88 of the 1951 revision of the Indian Act, thereby beginning the era of the Sixties Scoop. Indian women and Indian lands have been deliberately targeted and marginalized, vulnerable to being and becoming exploited.

By sharing with you, the reader, our Canadian timeline of history and each of the individuals mentioned above, we have to acknowledge this is our—yours and mine—Canadian leadership. Yes, you may not have directly suffered from this leadership but all Aboriginal, Inuit, Métis, and Indian people have. Treaty promises were not kept. Our land base of 100 percent has shrunk to less than 1 percent. Many people were starved into signing those Treaties for your benefit. Our natural food source, the buffalo, was slaughtered to near extinction. Our children were jailed in residential schools because of the Indian Act. Then in 1951, section 88 of the Indian Act gave authority to the Indian adoption project. It was against Canadian law for us to seek council to hire a lawyer, to leave the reservation, or to sell any goods, harvest, or butcher our own livestock without the permission of an Indian agent. Thinking back to Christopher Columbus, a thief and con artist who left his own country of Italy in 1492 in search of India to escape treason charges; thinking of all the ministers and nuns who raped and abused children and who were transferred to new missions by their leadership; thinking of past and present police officers, social workers, and teachers whose bosses or leadership allowed them to abuse their roles and their authority in power; thinking about how our British queen has not been able to protect us just as my own grandmother was not able to protect me. I do believe that people would care if I were to go missing. My family would care. My friends would care. The community I belong to would care. But I wonder if our police chief, mayor, or any of our local MLAs would care, me being no more important than any of our other missing and murdered women here in Canada. Sometimes I have considered what law could protect me or any other Aboriginal woman from marginalization, poverty, racism, and violence.

All these glimpses into my family and me have to do with sharing the truth as painful or shameful as it is. It has to do with having others become aware: violence and oppression has come from both men and women. Both kin and strangers have caused the abuse and violence. As Aboriginal women, there is much more we need to do to keep ourselves safe.

Long ago, we lived on the rez, also in Regina, but mostly in Saskatoon. This one time there was this big powwow for the queen. My grandmother wrapped a shawl around me and told me to go dance. I twirled and skipped around. The whole space was filled with so many dancers. I am in wonder all these years later that I fell, like a cocoon of the butterfly tree, ready to remove the silk robe of protection, ready now to fly back through time to find my grandmother and mother. Finally, now, after all these years, as a grandmother and mother, I have been initiated and accepted into the powwow circle. Forgive me. I was lost for so long. Please forgive my grandmother for not being there to protect me as a little girl. Forgive my grandmother for not being able to protect her children from the damages of Round Lake residential school.

First Nations people, we have expressed our heritage and spirituality through our art, beadwork, and apparel. Here is a small glimpse of the teaching of the shawl. Woman created garments that hold special meaning. It was said that long ago a mother created a shawl for her daughter. The young lady was preparing to leave her family to pursue her life’s dream. The shawl was said to have powers. It was created to protect the teachings that she gained in the early years. Throughout life, she was told, she would hold those teachings in high regard so she would be proud of who she was and of her family. The shawl would also protect her from the unseen hardships of an unknown world. Wrapped around her, it would keep her warm as the warmth of her mother’s arms. Cree Elder Mary Lee explains that “women were named after that fire in the center of the tipi”:

Woman in our language is iskwew . . . We were named after that fire, iskwuptew . . . In our language, for old woman, we say Notegwew. Years ago we used the term Notaygeu, meaning when an old lady covers herself with a shawl. A tipi cover is like that old woman with a shawl. As it comes around the tipi it embraces all those teachings, the values of community that the women hold. (quoted in Anderson, 100)

These values are still inscribed in our shawls of today such as when I created the shawl to be gifted to Her Royal Highness Prince Anne during her naming ceremony in 2007. In my artistic symbolism, I shared Our Grandmother Moon, a true symbol of leadership. She controls the water cycle on Mother Earth. As humans, we are made up in the same water proportion as Mother Earth. Our sacred hope of life for as long as the sun shines is that all nations will be treated equally for thirteen full moons all year around. I adorned her shawl with abalone shells to represent woman and the cycle of thirteen months, a connection to our mothers’ veins and balance of our grandmother. Seven rows of navy ribbon were used, for it is said that when leaders are forging ahead, they need to think seven generations forward. The beaded flowers represented our Little Rainbow, a young woman, and the Thunder Bird Beings gifted to us here on Earth, and the many colourful flowers across our lands so that all of us can enjoy the beauty. The Creator gifted the flowers, the rainbow, and the water to our Mother Earth. Having also learned from my Mennonite family that the rainbow is a promise from God, may you, me, and all of us remember to avoid being wicked or greedy to prevent the earth from becoming flooded again.

The Creator gave women clear responsibilities, and in the twenty-first century women are returning to their original authority. To all of the women in my life: Thank you for bringing me into this world, helping me to be, and to become. Grandmothers have wrapped me in their dress of tradition, respect, and grace. In their eyes, I’m sacred. Our mothers are the carriers of life and have given a wealth of energies. My roots, my sinew are sewn to them. I belong to this land. In her heart, I’m loved. My aunties, sisters, and girlfriends have taught me the language of woman. We have prayed. We have done and we have laughed together as one. Together we are the fabric of the nation. Together we are strong (Figure 3). Miyo-kīsikanisik kahkiyaw.

Figure 3. My late Mom, Winnifred George, attending my Grandmother’s wake and funeral. As a First Nations woman, I thank the women who came before me and passed down our traditions.

Figure 3. My late Mom, Winnifred George, attending my Grandmother’s wake and funeral. As a First Nations woman, I thank the women who came before me and passed down our traditions.

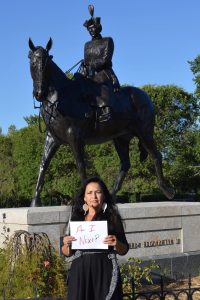

Figure 4. Asking Her Royal Highness The Queen, “Am I Next?”

Figure 5. My granddaughter and I dancing forward…

(All images are copyright protected and are the property of the author. No copying or usage is permitted for purposes other than within the context of this chapter.)

References

Aboriginal Women’s Action Network (AWAN). “Vancouver Advocating for Women’s Right to Power Over Her Life.”

Anderson, Kim. Life Stages and Native Women: Memory, Teachings, and Story Medicine. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2011.

Bagley, Christopher, and Kathleen King. Child Sexual Abuse: The Search for Healing. New York: Routledge, 1990.

Barron, F. Laurie. “Indian Agents and the North-West Rebellion.” In 1885 and After: Native Society in Transition, edited by F. Laurie Barron and James B. Waldram, 139–54. Regina: University of Regina Plains Research Center, 1985.

Amnesty International. Canada: Submission to the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women. London: Amnesty International, September 30, 2016.

Cook, Katsi. “Powerful Like a River: Weaving the Web of Our Lives in Defense of Environmental and Reproductive Justice.” In Original Instructions: Indigenous Teachings for a Sustainable Future, edited by Melissa K. Nelson, 154-67. Bear & Company, 2008.

Eneas, Bryan. “PAGC Conference: The Code of Silence.” PaNOW: Prince Albert. Right Now! (January 17 , 2017). Accessed http://panow.com/article/637185/pagc-conference-code-silence.

Sinclair, Raven. “Identity Lost and Found: Lessons From the Sixties Scoop.” First People’s Child & Family Review, 3, no. 1 (2007): pp. 65-82. Accessed http://journals.sfu.ca/fpcfr/index.php/FPCFR/article/view/25.

St. Pierre, Mark, and Tilda Long Soldier. Walking in the Sacred Manner: Healers, Dreamers, and Pipe Carriers. New York: Touchstone, 1995.

Wheaton, Cathy.

- This chapter weaves the stories of three women, Tracey George Heese, her mother, and her grandmother, with the history of Canada. We have italicized Winnifred’s (Tracey’s mother) words as Tracey reflects on what her mother might have thought. Tracey says, “I am telling my story in the hopes that it will benefit others and help them with their grief. May it help them rebuild when everything has been taken away. I also tell my story to keep my granddaughter safe.” ↵

- According to the City of Regina’s Historic Facts, Regina was referred to as oskana ka-asastēki, meaning “bone piles,” later translated as Pile of Bones. The city was so known because it became the site for depositing the bones of the bison slaughtered to make way for the “settlement” of the land https://www.regina.ca/about-regina/regina-history-facts/. ↵