5.4: Media

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 155424

We often speak of ‘the media’ as some amorphous social institution that is foisted upon us. In some ways this is true of all institutions and the mass media are no exception. But in other ways, this view glosses over the real people and social processes that create one of the biggest shapers of our worldview and outlook on life. Therefore, it is important to note who specifically makes the media content we all consumer. It may not be surprising at this point, but especially behind the scenes, the majority of the cultural gatekeepers; producers, directors and screenwriters are men. This creates a distortion of reality when it comes to whose stories are being told and becoming a part of the culture. For example, “a study, by sociologist Stacy L. Smith, analyzed 11,927 speaking roles on prime-time television programs aired in spring 2012, children's TV shows aired in 2011 and family films (rated G, PG, or PG-13) released between 2006 and 2011. Smith's team looked at female characters' occupations, attire, body size and whether they spoke or not.”71 Their analysis showed, regarding women employed in key behind the scenes roles for movies, only 18% of these positions were held by women from 1998 – 2012. The study also revealed similar results in primetime television. Although progress has been made, it has been slow. Children’s television programming follows a similar pattern as well with males about twice as likely as female characters. And when there are female characters they are more likely to be shown in sexy attire (in children’s programming!)72. Another study of G-rated films from 1990-2005 showed that only 28 percent of the speaking characters (both live and animated) were female and more than four out of five of the narrators were male. Finally, eighty-five percent of the characters were white73. What kinds of stories are being told? And what message might children take away from these stories presenting a ‘normal’ view of the world so heavily skewed?

Much of a child’s socialization is indirect, coming to them through observation, observation in their real- world experiences and observation of the media. Television, film, video games, social media, and other forms are involved in selecting, constructing and representing “reality.” In doing so, the media tend to emphasize and reinforce the values and images of those who create the messages and own the means of distribution. Thus, media play a large role in creating social norms, because various forms of media are present almost everywhere in current culture. In addition, the owners of distribution also take into account commercial (selling) considerations. As a result, the viewpoints and experiences of other people are often left out, or shown in negative ways. In Gendered Media: The Influence of Media on Views of Gender, Julia Woods explains:

“Three themes describe how media represent gender. First, women are underrepresented, which falsely implies that men are the cultural standard and women are unimportant or invisible. Second, men and women are portrayed in stereotypical ways that reflect and sustain socially endorsed views of gender. Third, depictions of relationships between men and women emphasize traditional roles and normalize violence against women.”

The underrepresentation of women has a two-pronged effect:

- We are tempted to believe there really are more men than women, and

- Men are the cultural standard.

In general, media continue to present both women and men in stereotyped ways that limit our perceptions of human capabilities. Typically men are portrayed as active, adventurous, powerful, sexually aggressive, and largely devoid of emotion. Women are often portrayed as sex objects who are usually young, thin, passive, dependent, and often incompetent or dumb. Female characters devote their primary energies to improving their appearances and taking care of homes and people and “landing” the perfect guy. And as far as stereotyping relationships for males and females in media, homosexuality is barely recognized and representations of bisexuality and asexuality are practically non-existent. Sex is a driving force behind advertising, because after all, sex sells...everything. But not just sex, heterocentric representations of sex. Women are often seen as dependent in sexual relationships while men are depicted as being independent and emotionally empty. And men are still portrayed (overwhelmingly) as breadwinners while women are typically awarded the roles of caregivers. Lastly, within the relationship sphere, women are typically represented as objects for men’s pleasure while men are still depicted most often as sexual aggressors. According to the feminist film critic Laura Mulvey (1975), this phenomenon is known as the male gaze. The male gaze is the idea that, within popular culture generally, women are portrayed as objects for men’s pleasure. The vast majority of media consumed in the United States depicts women from men’s point of view. An interesting case study in the male gaze happened in 2015 when Caitlyn Jenner first appeared on the cover of Vanity Fair magazine as a transgender woman she was immediately praised for her good looks. However, when she was known still known as Bruce Jenner she was praised for her athletic accomplishments and competition in the Olympics.

In order to create a medium which is universal, understandable, and acceptable for diverse recipients, senders very often use stereotypes, which fill the social life and evoke certain associations. For example, when you think of family, what do you see? When you think of a criminal or a victim, what do you see? When you think of a CEO or an assistant, what do you see? Maybe race, age, religion, or class came to mind, but almost certainly sex and gender played roles in all of the images. What sex and gender roles did you see when prompted to imagine a family? When I asked you to imagine a criminal and a victim, what sexes and genders were they? Almost always (and of course there are exceptions) people will imagine a nuclear heterosexual family structure with traditional gender roles. When prompted to imagine a criminal, people almost always imagine a male, and often people will see a victim as female. And when asked to imagine a CEO and an assistant, people will often imagine a male and female. But where did these images come from? Or at the very least, are they still being reinforced in popular imagery?

Another mechanism by which popular culture defines reality has come to be known as the smurfette principle. Coined by Katha Pollitt’s 1991 New York Times article,

"Contemporary shows are either essentially all-male, like "Garfield," or are organized on what I call the Smurfette principle: a group of male buddies will be accented by a lone female, stereotypically defined... The message is clear. Boys are the norm, girls the variation; boys are central, girls peripheral; boys are individuals, girls types. Boys define the group, its story and its code of values. Girls exist only in relation to boys."

We see this phenomenon in classics like Miss Piggy in the Muppets, Penny in the first three seasons of The Big Bang Theory, Princess Leia in Star Wars, April in Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Elaine Benes in Seinfeld, Gamora in Guardians of the Galaxy, and Black Widow in The Avengers. The messages portrayed by this trope contribute to the symbolic disempowerment by defining girls’ and women’s stories as unworthy of being told. The Hunger Games’ producer Nina Jacobson has spoken about the difficulty in convincing Hollywood studio executives that a female fronted film would be financially viable by appealing to more than just girls at the box office.74

However, mass media not only provides people information and entertainment, but, it also affects people’s lives by shaping their opinions, attitudes, values, beliefs, norms, and realities. So, how might media affect our interpretations of gender roles? In various forms of media, women and girls are more likely to be shown: in the home, performing domestic chores such as laundry or cooking; as sex objects who exist primarily to service men; as victims who can't protect themselves; and as the “natural” recipients of beatings, harassment, sexual assault or murder.

Men and boys are not exempt from being stereotyped in the media. From Don Draper to Jason Born to the Terminator, masculinity is often associated with economic success, competition, independence, emotional detachment, aggression, and violence. Despite the fact that men have considerably more economic and political power in society than women, these trends are very damaging to boys. Think for a moment how most disagreements between men are dealt with in popular culture: a fight, a car race, something to demonstrate whom the “better man” is through physical assertion.

Research tells us that the more television children watch, the more likely they are to hold sexist notions about traditional male and female roles. The problem arises when the traditional gender roles represented on in the media are so tightly constricting of the human potential, turning women into objects of men’s pleasure or care-takers and turning men into aggressors.

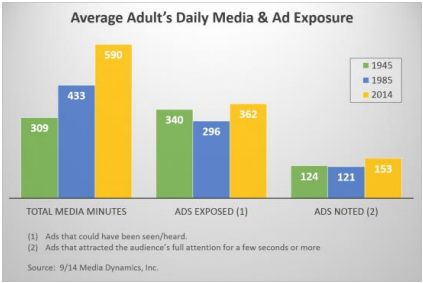

Advertisements are arguably the most pervasive form of media in our construction of reality. It’s estimated we are exposed to as many as 5,000 advertisements per day (and this is compared to about 2,000 ads per day just thirty years ago).75 This includes commercials, print ads, Brand labels, Facebook Ads, Google Ads, ads on your phone, or anything a business can produce to get your attention and compel you to buy. Some researchers estimate we are exposed to up to 20,000 ads per day, but those higher numbers not only include ads, but also include every time you pass by a label in a grocery store, all the ads in your mailbox whether you see them or not, the label on everything you wear, the condiments in your fringe, the cars on the highway, etc. However, just because we are in close proximity to an ad, doesn’t mean we saw it.

Figure \(5.4.1\) Bar Graph of "Average Adult's Daily Media & Ad Exposure"76

Consider the work of highly influential sociologist Erving Goffman. Specifically, his work on advertising and gender presentation and what he calls commercial realism. For Goffman, this is the way advertising portrays a world, which without critical reflection appears normal to us but is anything but (and should not appear normal or natural to us). This is one of the ways in which mass media influences how we see ourselves and learn to present ourselves in highly gendered manners. Advertisements in which women are portrayed as subordinate, weak, docile, delicate and fanciful contribute to what he calls ‘the ritualization of subordination’. This process helps to create (and recreate) a world in which to be feminine is to be less than and subordinate to a man. One that relies on the ‘benign-ness of the surround’ where women are perpetually at a disadvantage vis-a-vie men, blithely unaware of the world around them and men are showed in an opposite manner; poised, aware and ready to react. Consider this example Goffman outlines: body clowning. He says, “The use of entire body as a playful gesticulative device, a sort of “body clowning” is commonly used in advertisements to indicate lack of seriousness struck by a childlike pose (p. 50). It helps to present women in a manner that is not meant to be taken seriously (see: the blog “Women Laughing Alone With Salad”77). One way to notice the silliness of these sorts of images is to ‘flip the script’ by imagining the reverse image: men laughing alone with salad, for instance! If we monitor our reaction and are startled, we know a gender norm reinforced through advertising and commercial realism has been breached.

Perpetual discontent is a two-pronged advertising scheme, which emphasizes

- how broken and flawed we are, and

- how we can buy hope in the form of a product being sold.

Women in the U.S. are bombarded daily with advertising images that point out their flaws. They are constantly having it brought to their attention how they are too: thin, fat, short, tall, round, wrinkled, blond, brunette, red, dark, light, pale, freckled, flat, busty, etc. This trend is exceptionally cruel for teen and young adult women, but men are not exempt from the abuse of perpetual discontent. However, the media has created an unrealistic feminine ideal resulting in the desire to fulfill this impossible standard. This has resulted in women comparing their real selves to phony, made-up, photo-shopped images of women, and it also allows for men to judge real women against those constructed photos. This is not imply all men are sexually interested in women, or all women are concerned with how men are viewing them, but these are still two major themes sprouting from the media’s creation of gender and physical ideals. This media-created ideal has also commonly been blamed for the skyrocketing numbers of eating disorders as well as the rising numbers of cosmetic surgical procedures in the U.S. (especially among young women). At least 30 million Americans suffer from an eating disorder in their lifetime, and eating disorders are the 3rd most common chronic illness among adolescent females.78

Plastic Surgery Timelines

Figure \(5.4.2\) Numbers in Millions of Plastic Surgery Procedures between 1997-2015.

Not only has the media created an unrealistic feminine ideal that no one (and I mean no one!) can achieve, but media most often portray as being endlessly preoccupied by their appearance, and fascinated primarily by improving their appearance for the purpose of becoming sexually desirable to men. When children, specifically, are exposed to these messages, they internalize them and make them part of their own reality.

Furthermore, children are increasingly being exposed to messages about gender that are really intended for adult eyes only. Girls as young as six years old wanted to be more like dolls who were dressed in a sexy way and showing more skin than dolls who were dressed stylishly, but covered up.79 These young girls associated being sexy with being the way they wanted to look, being popular in school, and with whom they wanted to play. According to the American Psychological Association, girls who are exposed to sexual messages in popular culture are more likely to have low self-esteem and depression, and suffer from eating disorders.80

The media is perhaps one of the most underestimated elements of society. At the personal level people think of it in terms of convenience and entertainment rather than political influence, power, and control. However, advertising, in particular, has a slow cumulative affect on our perceptions of reality.

According to Debra Pryor and Nancy Nelson Knupfer, “If we become aware of the stereotypes and teach critical viewing skills to our children, perhaps we will become informed viewers instead of manipulatednconsumers.”81 Moreover, the commercials evolve along with the development of a society and are the answer to many social and political changes, such as emancipation of women, growing role of individualism, the dismantling of current gender roles reinforcing inequality. More and more advertising specialists produce non-stereotypical commercials, depicting people in non-traditional gender roles.nHowever, the attempts to break down the stereotypes threaten to reject the message; they challenge well-established “common sense”. Hence, a society has to achieve an adequate level of social readiness, so that messages breaking gender stereotypes could be effective.

Suggested Activities (adapted from Video and workbook, Minding the Set--Making Television Work for You)

Images - Using TV or video clips and magazine or newspaper pictures, chart similarities and differences in appearance and body size for the good and bad characters. Look again at the clips and make note of the type of camera shots used for the good and bad guys or gals. Compare the characters with self and peers and family members.

Working women - List the jobs that TV mothers have such as teacher, doctor. Do we ever see them working at their jobs? Does your mother have a job? If she works outside the home do you ever visit her there? Why or why not?

I'd rather be me - Form two groups - one of males, the other of females. From various media have the boys list female traits and interests that are most commonly featured, while the girls do the same for male characteristics and concerns. Form new mixed groupings and discuss how males and females feel about the stereotypes by which their sex category and gender have come to be represented. Is there anything artificial about these stereotypes?

Jobs - Examine the media to determine how certain occupations are portrayed, and then interview people in those occupations to ascertain how realistic portrayals are. Count the number of women or men portrayed in jobs. List the types of jobs for women and men portrayed. How do these findings compare to the jobs held by the parents of students?

Posed photos - Select pictures from magazines ads that show the difference between posed photographs of females and males (this can include children, as well). Describe what is emphasized for each.

Twisted tales - Rewrite a fairly tale from the point of view of the opposite sex.

Video games - Design a video game for girls and boys that is not stereotypical or violent.

71 http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/1...n_2121979.html

72 www.now.org/issues/media/women_in_media_facts.html

73 www.now.org/issues/media/women_in_media_facts.html

74 http://www.kcrw.com/news-culture/sho...games-producer

75 Papazian, Ed. TV Now and Then: How We Use It; How It Uses Us. January, 2016. Media Dynamics, Inc. http://www.mediadynamicsinc.com/prod....YYd2J5FB.dpuf

76 Media Dynamics, Inc. retrieved from TV Now and Then: How We Use It; How It Uses Us.

77 http://womenlaughingalonewithsalad.tumblr.com/

78 Hudson, J. I., Hiripi, E., Pope, H. G., & Kessler, R. C. (2007). The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the

national comorbidity survey replication. Biological Psychiatry, 61(3), 348–358.

79 Jennifer Abbasi. 2012. Why 6-Year-Old Girls Want To Be Sexy. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/07/17/6-year-

old-girls-sexy_n_1679088.html. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

80 American Psychological Association,Task Force on the Sexualization of Girls. (2007).Report of the APA Task Force on

the Sexualization of Girls. Retrieved fromhttp://www.apa.org/pi/women/prog...eport-full.pdf

81 Pryor, Debra; Knupfer, Nancy Nelson, 1997 Gender Stereotypes and Selling Techniques in Television Advertising:

Effects on Society.http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICDocs/data/ericdocs2sql/content_storage_01/0000019b/80/16/c4/8c.pdf,

retrieved 10 November 2016.