8.1: A Very Brief History of Education in the United States

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 156280

By 1850, all 50 states had established government-funded schools in which White children (of any social class) could attend. Black children were formally excluded from public education opportunities until after the Civil War; and even after the Civil War, schools remained segregated. In 1867 the Department of Education was established, and its primary role was to collect information on schools and teaching that would help the States establish effective school systems.224 By 1870, public schools were present in every state with secondary public schools outnumbering private schools. However, three years later in 1873, an economic depression hurt formal education. Many schools closed because they lacked the funds to staff the school with teachers and supplies.

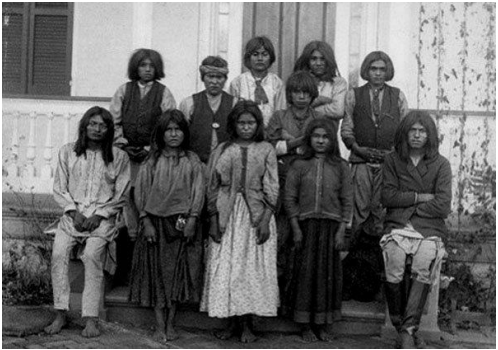

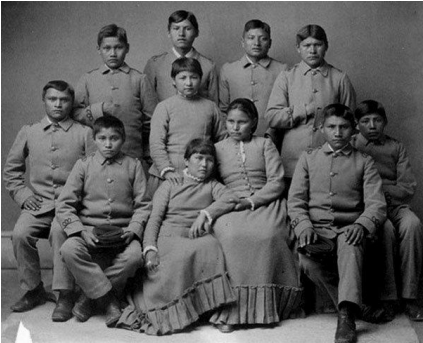

During this time, public schools remained racially segregated. Native American Boarding Schools (also known as Indian Boarding Schools) were established by the U.S. government in the late 19th century, using a model based off an education program designed in Fort Marion Prison in St. Augustine, Florida experimenting with Native American assimilation education on imprisoned and captive Indigenous people. In 1886 Army Captain Richard Henry Pratt opened one of the most well-known of these schools, the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania. Attendance to the boarding schools was made mandatory by the U.S. Government regardless of whether or not Indigenous families gave their consent. Pratt's educational goal for American Indians was to “civilize them” through total and forced cultural assimilation - an attempt to eliminate entire cultures and peoples. This philosophy meant administrators forced students to speak English, were assigned Anglo-American names, had their hair cut or buzzed, and forced to wear military-style uniforms in exchange of their traditional clothing. As Pratt put it in an 1892 speech: “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.”225 Carlisle was one of 357 Indigenous boarding schools that operated throughout the country.

Figure \(8.1.1\): Photo Source: John N. Choate. Boys and girls pose outdoors at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, in Carlisle, Pa., after their arrival at the boarding school from For Marion, Fla.226

Figure \(8.1.2\): Photo Source: John N. Choate. The same INdian students (from the previous image) are shown four months after arriving at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School.227

In 1896, the Supreme Court decision of Plessy v. Ferguson established separate public schools for black and white students. The decision also deprived African American children of equivalent educational advantages. Schools for Black children had to make do with scant financial support and negligible resources. There were typically far too few teachers, too many students, and students of all ages (from toddler to teen) in one schoolhouse (which is really one school room). Often times, schools for Black children were so underfunded (or not funded at all) that building these centers for learning were privately founded by Black women. Teaching was an attractive career for Black women for economic reasons, but also because it was an alternative to working in a White family’s house in a domestic role.

It was not until 1832 that women were allowed to attend college with men. Oberlin College in Ohio was the first co-ed college in the U.S., and it was also the first White college to admit Black students. Progressive? Maybe. But are you ready for this?! Female students were expected to remain silent in lecture halls ad during public assembly. AND they were required to care for themselves as well as do the laundry for male students, clean the male students’ rooms, and serve male students their meals. Can you imagine?! Think about some of the students in your class. If you are a female, imagine having to do the laundry of some of your male classmates to be able to learn at the same university. And if you’re male, imagine expecting your female classmates having to do your laundry and serve you meals. Hopefully (and maybe I am being too hopeful here) we can all agree the inequality was apparent and disturbing, at best.

In addition to having to accomplish domestic roles to serve male students, female students were often channeled into areas of study including home economics, elementary education, and nursing; whereas male students were often encouraged to enter areas of study such as engineering, physical and natural sciences, business, law, and medicine. We will discuss how some of these trends persist today later in the chapter.

In 1896, the Supreme Court decision of Plessy v. Ferguson established separate public schools for Black and White students. The decision also deprived African American children of equivalent educational advantages. Schools for Black children had to make do with scant financial support and negligible resources. There were typically far too few teachers, too many students, and students of all ages (from toddler to teen) in one schoolhouse (which is really one school room). Often times, schools for Black children were so underfunded (or not funded at all) that building these centers for learning were privately founded by Black women. Teaching was an attractive career for Black women for economic reasons, but also because it was an alternative to working in a White family’s house in a domestic role.

The government funded schools available to White children had to two major outcomes:

- White female literacy raised to meet the rate of White male literacy; and

- The increase in elementary schools across the country

allowed for more career opportunities for woman as school teachers. Because of the proliferation of schools in the U.S. in the late 1800s and early 1900s, teaching became a full-time job, and largely dominated by women. However, this job paid far too little to support a family, so as a result, school administrators employed women in large numbers as cheap and efficient means to implement mass education.

As far as college education, it was not until 1832 that women were allowed to attend college with men. Oberlin College in Ohio was the first co-ed college in the U.S., and it was also the first racially segregated college to admit Black students. Progressive? Maybe. But are you ready for this? Female students were expected to remain silent in lecture halls and during public assembly. AND they were required to care for themselves as well as do the laundry for male students, clean the male students’ rooms, and serve male students their meals. In fact, female students were excused from class on Mondays to fulfill their domestic responsibilities at the college. Can you imagine?! Think about some of the students in your class. If you are a female, imagine having to do the laundry of some of your male classmates to be able to learn at the same university. And if you’re male, imagine expecting your female classmates having to do your laundry and serve you meals. Hopefully (and maybe I am being too hopeful here) the inequality is apparent and disturbing, at best.

In addition to having to accomplish domestic roles to serve male students, female students were often channeled into areas of study including home economics, elementary education, and nursing; whereas male students were often encouraged to enter areas of study such as engineering, physical and natural sciences, business, law, and medicine. We will discuss how some of these trends persist today later in the chapter.

The Progressive Era (18902-1930s) was notable for a dramatic expansion in the number of schools and students served, especially in the fast-growing metropolitan cities. After 1910, smaller cities also began building high schools. By 1940, 50% of young adults had earned a high school diploma.228 The Civil Rights Movement during the 1950s and 1960s helped publicize the inequities of segregation. In 1954, the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education unanimously declared that separate facilities were inherently unequal and unconstitutional.

By the 1970s segregated districts had practically vanished in the South. Although required by court order, integrating the first Black students in the South was met with intense opposition. In 1972 Title IX was passed, making discrimination against any person based on their sex in any federally funded educational program(s) in America illegal.229

By 1980, women were enrolled in American colleges at the same rate as men, and by 1982 women actually earned more bachelor’s degrees than men. It wasn’t until 1987 that women began earning more Master’s degrees than men. Were you alive in 2005? Because it wasn’t until that year that women earned the majority of doctoral degrees in the United States.230

Although full equity in education has still yet to be achieved, technical equality in education had been achieved by the early 1970s.

224 U.S. Department of Education. The Federal Role in Education. Revised 6/2021. https://www2.ed.gov/about/overview/f...hool%20systems.

225 Churchill, W. (2004). Kill the Indian, save the man: The genocidal impact of American Indian residential schools. San Francisco: City Lights.

226 Photo by John N. Choate is in the public domain

227 Photo by John N. Choate is in the public domain

228 US Census Bureau. (2017). High School Completion Rate Is Highest in U.S. History. Revised October 2021. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/pres...ics%20division.

229 U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972. Reviewed October 2021. https://www.hhs.gov/civil-rights/for...l%20assistance.

230 Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, Women Can’t Win: Despite Making Educational Gains and Pursuing High-Wage Majors, Women Still Earn Less than Men, 2018