Introduction - An Open Invitation to LGBTQ+ Studies

- Page ID

- 165171

At the 1984 Hacker’s Convention, Stewart Brand reportedly uttered the classic phrase “Information wants to be free.”[1] Among this statement’s several interpretations is the one reflecting a belief that all people should be able to freely access information and that scientific information should be openly circulated. And I would like to suggest that if information wants to be free, queer information, especially, should always be free.

This textbook is dedicated to the bold idea that information and education should be free and widely accessible across age, race, class, gender, and other categories—such as the nation-state—that are all too often invoked to divide peoples. In the last few years we have experienced a global pandemic, the rise of a radical form of domestic political extremism, a racial reckoning sparked by the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, and the revival of 1990s-style culture wars that are not struggles over culture but really about politics and power. In this volatile context, this textbook is more important than ever, especially as nearly one in five young adults globally who are members of Generation Z (born after 1997) identify as not being straight and almost 4 percent as not being cisgender.[2] Free and empowering information is the only answer to the politics of hatred and divisiveness.

The information in this textbook can empower readers because it provides an introduction to and an overview of LGBTQ+ studies for college students and the curious public. It is an Open Educational Resource (OER), which means that it carries an open license so that all its content can be retained, reused, revised, remixed, and redistributed for free, as long as authorship is clearly attributed. The State University of New York (SUNY) Geneseo’s Milne Library is publishing and maintaining this free, online resource. Additionally, SUNY Press is publishing paperback and hardcover copies of the textbook for those who would like to hold the text in their hands.

Producing an open-license textbook for LGBTQ+ studies embodies the spirit of the political struggle for the rights of gender and sexual minorities that also animates the field itself. This textbook is free for everyone to use; it is community oriented and a cultural production grounded in the struggle to challenge stereotypes, silences, and untruths that have long been circulated about lesbians, gays, bisexuals, trans folk, queer and nonbinary people, our histories, and our cultures. It’s a kind of DIY LGBTQ+ project for the twenty-first century. It also helps combat the high cost of a college education in the United States, and around the world. Students all too often simply cannot afford to purchase textbooks for their classes because the books cost too much.

This political struggle for the human rights of gender and sexual minorities continues today. Research and writing on LGBTQ+ issues remains vitally important. Equality has advanced in the United States—there is federal recognition of marriage equality, for example, and enhanced visibility for transgender issues on many college campuses—but simultaneously, backlash and hostility toward LGBTQ+ people is widespread. LGBTQ+ people continue to experience hate crimes at unacceptable levels, and state legislators continue to try to pass anti-LGBTQ+ laws and ordinances.[3] Similarly, there are advances in terms of global LGBTQ+ rights—India and Jamaica, two former British colonies, have struck down colonial-era laws against homosexual activity—but violations of LGBTQ+ human rights still occur worldwide. This textbook speaks directly to a broad range of audiences by engaging these critically important social issues.

This textbook fills a number of needs for both academic readers and the general public. First, it is the only free, openly licensed textbook on LGBTQ+ issues in the world. It offers accessible, academically sound information on a wide range of LGBTQ+ topics—history, relationships, families, parenting, health, and culture—and a chapter on how to conduct research in LGBTQ+ studies. Second, it employs an intersectional analysis, highlighting how sexuality and gender are simultaneously experienced and constructed through other structures of inequality and privilege, such as race and class. This intersectional analysis is grounded in social theory and a commitment to racial equality. Third, it expands the temporal and spatial perspectives on LGBTQ+ issues, from the ancient world to more contemporary regions. Finally, it aims to support multiple learning styles by integrating visual elements and multimedia resources throughout the textbook.

This textbook has evolved over several years of research, writing, and—most importantly—collaboration with a host of colleagues across the United States and indeed the world. It was originally borne out of my experience teaching the Introduction to LGBTQ+ Studies course in the online environment at SUNY Empire State college. SUNY Empire students are typically older (average age thirty-six), working full or part time, and taking care of their families, including parents, children, or both. They are struggling to secure a college degree and to learn more about the world they live in. What is most striking about the students in the class—whether they identify as LGBTQ+ or straight—is both their genuine curiosity and their deep desire to learn more so that they can advocate for LGBTQ+ family members or serve as allies to friends and colleagues in the workplace. Many work in human services, health care, or in educational settings, and they want to know more about how to better support LGBTQ+ youth and fight the discrimination they witness. The textbook for this class cost $93, and I found myself buying textbooks for students when they could not afford them. Out of these experiences came this textbook, an answer to the need for access to critically important information on LGBTQ+ lives, for free.

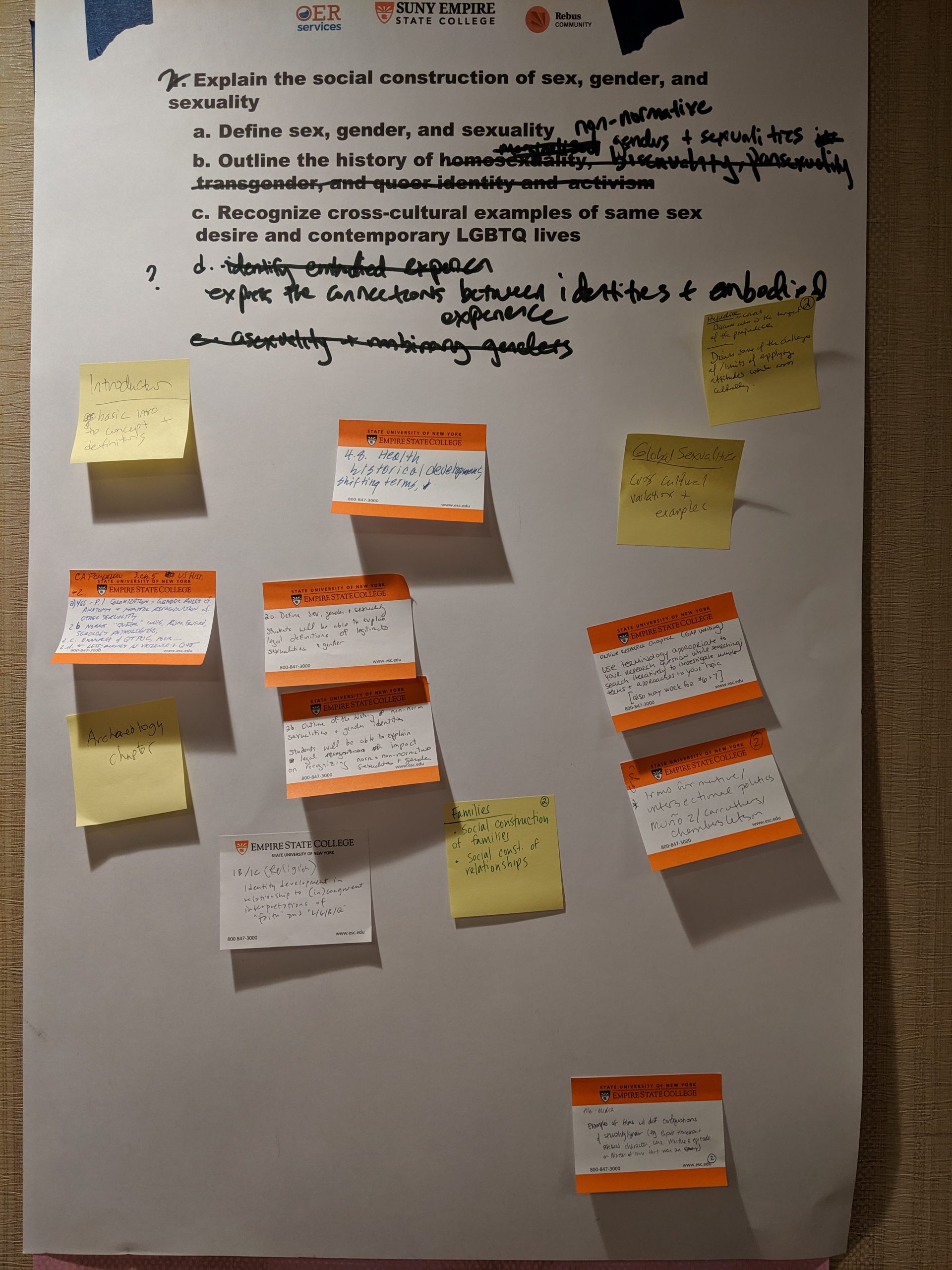

In January 2019 a call for participants to create this textbook, placed through the Rebus Community platform, received dozens of answers from people within forty-eight hours. I and Sean Massey, who agreed to serve as coeditor, sifted through dozens of impressive résumés to find the right mix of proposed topics, relevant expertise, and comprehensive coverage. Thanks to a grant from SUNY OER Services, we were able to hold a workshop in Saratoga Springs in spring of 2019, where most of the authors met, shared their work, brainstormed learning outcomes and textbook design, and generally enjoyed each other’s company. During 2019, each chapter was peer reviewed at least once and reviewed by the coeditors, and the entire textbook was also peer reviewed. The beta version of the textbook launched in spring 2020 through SUNY OER Services.

On the basis of feedback about that version, we recruited Jennifer Miller to organize a chapter on LGBTQ+ literature, which strengthened part 6, on LGBTQ+ culture. Along the way, she became a coeditor. Subsequently, SUNY Press joined the project, and the entire textbook was substantially revised to include pedagogical supports and create a uniform structure. Allison Brown served as project manager and digital publishing expert for the entire project. She also served as an editor and developed key content for the pedagogical supports. Her expertise in digital publishing, deft project management skills, and cool, calm influence have kept the project on track and moving in the right direction for four long years. We hope you enjoy the results of our efforts.[4]

The next section defines LGBTQ+ studies and situates the textbook within the field. The last section provides an overview of the organization of the textbook so that readers will have a sense of the range of topics and ideas that they will encounter.

WHAT IS LGBTQ+ STUDIES?

LGBTQ+ studies examines issues relating to sexual orientation and gender identity, usually focusing on lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, and queer people—hence the initialism LGBTQ—and their histories and cultures. In the twenty-first century, that collection of identities has expanded to include asexual, questioning, intersex, and two-spirit peoples and myriad other genders and sexualities—hence the plus sign in LGBTQ+. The field relies on and benefits from interdisciplinary methods to arrive at new ideas and theories, and it has always been closely aligned with different forms of political activism. This means that scholars in LGBTQ+ studies might combine historical analysis with ideas from literary analysis to make sense of their own experience or the experiences of others with whom they have conducted fieldwork. Finally, the field is hard to categorize simply because it is always evolving and always questioning the politics and poetics of its own practitioners. In fact, different names have marked different periods in the field; it was gay and lesbian studies in the beginning, then came the birth of queer theory in the 1990s, and we call it LGBTQ+ studies now. However it is described, LGBTQ+ studies is dedicated to the simple notion that discrimination against human sexual and gender diversity is wrong. Rather, gender and sexual diversity are to be valued and celebrated but also critically analyzed and theorized, for everyone’s benefit.

LGBTQ+ studies as a field of inquiry has grown out of various liberation movements in the latter half of the twentieth century in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada. Indeed, interdisciplinary academic fields have a long history of emerging in response to activist movements and the accompanying demands to understand and legitimate the histories, literatures, and cultures of oppressed peoples. For example, in the United States the civil rights and Black power movements of the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s gave rise to Black studies, and feminist movements of the 1960s and 1970s gave rise to women’s studies, or gender studies as it is now often known. As Alisa Solomon and Paisley Currah argue, “LGTBQ studies has its origins in the gay activism that marks its symbolic birth with the Stonewall uprising of 1969.”[5] Leaders in what was initially called gay and lesbian studies were also active in lesbian, feminist, gay, and trans liberation movements in the United States and United Kingdom, including Esther Newton, Jeffrey Weeks, Larry Kramer, Jonathan Ned Katz (founder of Gay Academic Union), and Leslie Feinberg.[6]

At a very basic level, what was originally called the gay liberation movement gave birth to a new field—gay and lesbian studies. In this field, scholars developed new analyses and research methodologies to challenge the silences and erasure of lesbian and gay lives from history, art, politics, and public policy. Activists and scholars sought to build new institutions and transform old ones. Gay interest groups within academic professional organizations were organized, and archives such as the Lesbian Herstory Archives (in 1974) were set up to safeguard histories, memorabilia, and literature that document lesbian experience. Community centers were founded to provide social, psychological, and material support for community members, and cultural institutions were established to ensure the creation and production of literature, music, and art. Olivia Records was founded in 1973 by radical lesbian feminist members of the Washington, D.C., collective the Furies and the Radicalesbians, and the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival was founded in 1976.

Another key component of our definition of LGBTQ+ studies is a form of analysis called intersectional feminism that emerged in the 1980s as Black lesbians critiqued racism within the white women’s movement (and women’s studies) and sexism and homophobia among Black activists (and in Black studies). Radical women of color set about creating their own institutions and articulating their own theories, including the Combahee River Collective in Boston and Kitchen Table Press (founded in 1980). The Combahee River Collective Statement is an important, early statement of intersectional feminism.[7] Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term intersectionality in 1989 as part of her work in critical race theory. The importance of this analysis has not diminished, as evidenced by Crenshaw’s 2016 Ted Talk, “The Urgency of Intersectionality.”[8]

By the 1990s, the HIV/AIDS pandemic had started to decimate gay communities, creating a sense of fury and desperation among gays and lesbians and a growing mainstream backlash as well. Lesbian and gay activism took increasingly radical approaches, perhaps best exemplified by ACT UP—the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power—and Queer Nation. These groups articulated a radical critique of straight culture and developed revolutionary tactics to disrupt business as usual and push the U.S. medical establishment to attend to the ravages of the disease. Within academic contexts, queer theory was born, and perhaps most closely identified with the work of theorists like Michel Foucault, Judith Butler, and Eve Sedgwick (see chapter 1, “Thirty Years of Queer Theory”). At the same time, in a synergistic relationship among activist movements, the academy, and human services, new names for a broader array of sexual and gender identities emerged, including trans and queer. And somewhere along the way, the meanings of gender and sexuality became much more complicated.

The story of LGBTQ+ studies is complicated, ongoing, and hard to understand, but one important element is that it emerged in relationship to historical and political forces hard at work in the late twentieth century. Moreover, we emphasize that our definition of LGBTQ+ studies is a broad and inclusive one. We rely on an intersectional feminist analysis to remind us that discrimination and oppression are not simple, unilinear forces. Rather, multiple interlocking systems of discrimination—including racism, sexism, and homophobia—affect all our lives in different and complex ways. An additional goal of this textbook is to embrace the original impulse of queer theory to challenge and disrupt the conventions of straight, white, middle-class America. And we heed the call of trans theory to think against the grain and across traditional definitions of sexuality and gender. Finally, in the new millennium of the twenty-first century, we embrace and seek to celebrate and empower nonbinary gender and sexual identities and thinking. To get a sense of the breadth and depth of this gender and sexual revolution, review PFLAG’s “National Glossary of Terms.”[9]

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Chapter 1: Thirty Years of Queer Theory

- Identify key approaches and debates within the field of queer theory.

- Explain the social construction of sex, gender, and sexuality.

- Describe the relationship among LGBTQ+ history, political activism, and LGBTQ+ studies.

- Summarize the personal, theoretical, and political differences of the homophile, gay liberation, radical feminism, LGBTQ+ rights, and queer movements.

Chapter 2: Global Sexualities

- Identify key approaches used in LGBTQ+ studies, including anthropology.

- Define key terms relevant to particular methods of interpreting LGBTQ+ people and issues, such as anthropology and ethnography.

- Identify cross-cultural examples of same-sex desire and contemporary LGBTQ+ lives.

- Describe the connections between identities and embodied experiences.

- Describe intersectionality from an LGBTQ+ perspective.

- Analyze how key social institutions shape, define, and enforce structures of inequality.

- Describe how people struggle for social justice within historical contexts of inequality.

- Identify forms of LGBTQ+ activism globally.

Chapter 3: Queer New World

- Define LGBTQ+ studies and queer theory, and explain why queer theory matters in the field of archaeology.

- Explain the social construction of sex, gender, and sexuality in both the present and the ancient past.

- Define key terms such as heteronormativity, gender performativity, and binary oppositions, and explain how they influence interpretations of the past.

- Describe intersectionality from an LGBTQ+ perspective.

- Discuss archaeology as a key subfield within LGBTQ+ anthropology.

Chapter 4: U.S. LGBTQ+ History

- Explain the social construction of sex, gender, and sexuality.

- Summarize the history of nonnormative genders and sexualities, including homosexuality, bisexuality, and transgender identity, as well as queer identity and activism.

- Describe intersectionality from an LGBTQ+ perspective.

- Analyze how key social institutions shape, define, and enforce structures of inequality.

- Describe how people struggle for social justice within historical contexts of inequality.

- Describe several examples of LGBTQ+ activism, particularly in relation to other struggles for civil rights.

- Identify key approaches used in LGBTQ+ studies, including the study of LGBTQ+ history.

- Define key terms relevant to particular methods of interpreting LGBTQ+ people and issues, such as history and primary sources.

- Describe the relationship between LGBTQ+ history, political activism, and LGBTQ+ studies.

- Summarize the personal, theoretical, and political differences of the homophile, gay liberation, radical feminism, LGBTQ+ rights, and queer movements.

Chapter 5: LGBTQ+ Legal History

- Describe how people struggle for social justice within historical contexts of inequality.

- Recognize that progress faces resistance and does not follow a linear path.

- Identify key approaches within LGBTQ+ studies, and discuss at least the legal history approach in detail.

Chapter 6: Prejudice and Discrimination against LGBTQ+ People

- Describe the connections between identities and embodied experiences.

- Analyze how key social institutions shape, define, and enforce structures of inequality.

- Describe how people struggle for social justice within historical contexts of inequality.

- Explain how different understandings of sexuality and gender affect self- and community-understanding of LGBTQ+ people.

Chapter 7: LGBTQ+ Health and Wellness

- Summarize the history of nonnormative genders and sexualities, including homosexuality, bisexuality, and transgender identity, as well as queer identity and activism.

- Describe the connections between identities and embodied experiences.

- Describe intersectionality from an LGBTQ+ perspective.

- Analyze how key social institutions shape, define, and enforce structures of inequality.

Chapter 8: LGBTQ+ Relationships and Families

- Explain the social construction of sex, gender, and sexuality.

- Describe the ways that LGBTQ+ people form relationships and the configurations of LGBTQ+ relationships.

- Describe the myths that exist regarding the quality of LGBTQ+ relationships and the research that refutes those myths.

- Describe how people struggle for social justice within historical contexts of inequality.

- Describe some of the negative consequences of homophobia, heterosexism, and minority stress and the ways LGBTQ+ people manage those consequences.

- Identify different types of LGBTQ+ family formations, including challenges to family formation and family building.

- Describe sources of stress and buffers for LGBTQ+ families and for LGBTQ+ individuals within their families of origin.

- Analyze how key social institutions shape, define, and enforce structures of inequality.

- Describe challenges that some LGBTQ+ families have in interacting with public and private systems, including legal, health care and human services, and educational systems.

- Describe the relationship between LGBTQ+ history, political activism, and LGBTQ+ studies.

- Articulate the queer viewpoint on LGBTQ+ relationships and families.

Chapter 9: Education and LGBTQ+ Youth

- Describe the connections between identities and embodied experiences.

- Recognize the steps of coming out and the range of responses for gender and sexuality identities.

- Describe how people struggle for social justice within historical contexts of inequality

- Differentiate between the components making schools supportive and inclusive and those needing improvements.

- Assess resources for LGBTQ+ youth facing discrimination, oppression, and marginalization.

- Describe intersectionality from an LGBTQ+ perspective.

- Analyze how key social institutions shape, define, and enforce structures of inequality.

- Identify health and education disparities for minoritized gender and sexuality identities.

Chapter 10: Screening LGBTQ+

- Summarize the cinematic history of nonnormative genders and sexualities, including homosexuality, bisexuality, and transgender identity.

- Summarize the history of film censorship as it relates to nonnormative genders and sexualities, including homosexuality, bisexuality, and transgender identity.

- Identify key approaches to critiquing explicit and coded LGBTQ+ identities and themes in film.

- Discuss at least one approach in detail and apply it to an original interpretation of queer film.

Chapter 11: LGBTQ+ Literature

- Identify and describe resistance to LGBTQ+ cultural representations specific to literary fields (e.g., comics, children’s literature).

- Explain how LGBTQ+ content creators overcame censorship to create varied and complex representations of LGBTQ+ identities, desires, and lives.

- Describe tropes that emerge in particular fields of LGBTQ+ literature.

- Explain literature’s role in identity and community formation.

OVERVIEW OF THE TEXTBOOK

This textbook is organized into seven parts, each with one or more chapters that provide a broad overview on a particular topic in a disciplinary approach. Each chapter starts by stating the relevant learning objectives and ends with a “Key Questions” section for class discussion that points back to those objectives. Pedagogical supports include resources listed at key places in the chapter and at the chapter’s end, with discussion questions or suggestions for learning activities, such as presentation topics, creative responses, and debate questions. Many chapters also include one or more “Profile” sections, which provide in-depth looks at particular issues relevant to the broader topic of the chapter. Glossaries are at the end of each chapter.

Part I, “Theoretical Foundations,” consists of chapter 1, “Thirty Years of Queer Theory,” by Jennifer Miller. It examines the emergence of queer theory and queer theoretical interventions into understandings of gender and sexual identities. It identifies key concepts and theorists in queer theory, and it explores queer theory at the intersection of gender, race, and ability.

Part II, “Global Histories,” explores different understandings and manifestations of gender and sexuality throughout history and from a global perspective. It provides readers with a historically based understanding of LGBTQ+ identities, lives, and rights in the United States and the complex ways these phenomena have changed and been contested over time. Its two chapters explain how gender and sexual diversity is the rule, rather than the exception, across all human cultures. In chapter 2, “Global Sexualities: LGBTQ+ Anthropology, Past, Present, and Future,” Joseph Russo delineates the many functions, meanings, practices, and methods of conceptualization for sexuality. Across different cultures and societies, as well as throughout history, sexuality has come to define an entire spectrum of phenomena. Two profiles accompany this chapter. Rita Palacios introduces the work of the muxe artist and anthropologist Lukas Avendaño in Mexico. Adriaan van Klinken’s profile positions LGBTQ+ identities within the pan-African decolonization movement and specifically in relation to religion and LGBTQ+ activism.

Chapter 3, “Queer New World: Challenging Heteronormativity in Archaeology,” by James Aimers, explores how new theories of sex and sexuality that have emerged from feminist studies, gender studies, and queer theory have changed the way we see the lives of ancient people. In particular, the assumption that heterosexuality and heteronormativity is and always has been the norm in human culture is challenged. In particular, Aimers describes nonheteronormative behaviors and identities in ancient Mesoamerica. Both chapters help us rethink some of our basic assumptions about gender and sexuality and what is “normal.”

Moving from a global perspective, part III focuses on U.S. histories in relation to LGBTQ+ lives. In chapter 4, “U.S. LGBTQ+ History,” Clark Pomerleau traces the development of LGBTQ+ concepts, identities, and movements in the United States from white settler colonialism through the nineteenth century. The broadening from thinking of sexuality as behavior to sexuality as identity is highlighted, as is the subsequent development of homosexual communities in the twentieth century. Toward this end, the profile by Jennifer Miller and Clark Pomerleau documents how the science of sexology introduced the idea that same-sex attraction was a pathological identity born of mental illness that correlated with gender transgression. Pomerleau’s chapter also evaluates the political strategies that influenced LGBTQ+ organizing, including the civil rights movement, radical Left tactics, and cross-pollination from 1960s and 1970s student organizing and feminism. Pomerleau sketches how, in response to the AIDS epidemic, LGBTQ+ Americans developed institutions and new forms of political activism that included the rise of queer politics.

In chapter 5, “LGBTQ+ Legal History,” Dara Silberstein explores the history of constitutional law in the United States and how it has served as the context for critical LGBTQ+ legal battles. She considers the tenets that paved the way for recognition of sexual rights and the process that eventually led the Supreme Court to extend these rights to include lesbian and gay people. The chapter addresses the question of marriage equality. This overview of LGBTQ+ legal history is supplemented by Ariella Rotramel’s profile on anti-LGBTQ+ hate crimes in the United States. The profile defines hate crimes and summarizes the history of hate-crime laws, at both the federal and the state levels. A map in the profile depicts the very uneven development of hate crime laws across the United States, notwithstanding ongoing violence against LGBTQ+ people.

Part IV, “Prejudice and Health,” begins by drawing on social psychology research to understand how discrimination and prejudice affect LGBTQ+ people. In chapter 6, “Prejudice and Discrimination against LGBTQ+ People,” Sean Massey, Sarah Young, and Ann Merriwether emphasize that even though there have been great strides in recent years in terms of LGBTQ+ acceptance in the United States and elsewhere, ongoing forms of prejudice, discrimination, and violence remain. Their chapter reviews the prevalence and trends of anti-LGBTQ+ prejudice in the United States; sets out what is known about its nature, origins, and consequences; provides a historical overview of attempts to define and measure it; and reviews the variables that increase or reduce its impact on the lives of LGBTQ+ people. Finally, they also discuss the resistance and resilience shown by the LGBTQ+ community in response to prejudice and discrimination.

In the accompanying profile, “Minority Stress and Same-Sex Couples,” David Frost analyzes discrimination and structural violence on same-sex couples that results in minority stress. He and his colleagues have conducted several studies to understand how sexual minority individuals and members of same-sex relationships experience stigma related to their intimate relationships. He demonstrates that stigma harms their mental health and the quality of their relationships.

Chapter 7, “LGBTQ+ Health and Wellness,” explores the history and culture of medicine in relation to LGBTQ+ people. The authors—Thomas Long, Christine Rodriguez, Marianne Snyder, and Ryan Watson—consider vulnerabilities across the lifespan and across intersectional identities and disease prevention and health promotion. These experts identify both the negative outcomes for LGBTQ+ peoples’ health and the resistance by LGBTQ+ people to the pathologizing of queer sexuality. Queer communities have sought to take health into their own hands, particularly in relation to the HIV/AIDS epidemic. The authors also discuss mental health and transgender people’s health, and they conclude with advice on how to be a smart patient and health care consumer.

Part V, “Relationships, Families, and Youth,” continues to draw on psychology research to explore LGBTQ+ relationships and families and the experiences of youth in educational settings. In chapter 8, “LGBTQ+ Relationships and Families,” Sarah Young and Sean Massey explore the complex worlds of LGBTQ+ intimate relationships and the varied ways that LGBTQ+ people form families. In her profile, “LGBTQ+ Family Building: Challenges and Opportunity,” Christa Craven shares insights from her research on the reproductive challenges and experiences of loss that many lesbian and gay couples in the United States face. She argues that support resources should be more inclusive, to help LGBTQ+ families who experience reproductive loss.

In chapter 9, “Education and LGBTQ+ Youth,” Kim Fuller identifies the social and educational barriers to healthy LGBTQ+ youth development, such as inequities and injustice. She also shows the resiliency of LGBTQ+ youths and the role supportive adults can assume in facilitating positive youth development. She describes the coming out process for young people and how educational institutions and settings can sabotage or support that process. In the profile complementing this chapter, Sabia Prescott reviews the current state of LGBTQ+ inclusion in prekindergarten through twelfth-grade educational settings and its consequences for learning outcomes for LGBTQ+ youth.

Part VI, “Culture” encompasses two important realms of LGBTQ+ life: film and literature. In chapter 10, “Screening LGBTQ+,” Lynne Stahl reviews various forms of LGBTQ+ film and media from the beginnings of the cinematic form to the contemporary milieu of producing DIY web series and viewing on smartphones. The chapter addresses milestone films and other visual media along with significant laws, political contexts, technological developments, genres, movements, and controversies, primarily in the United States. Stahl’s analysis reveals that other structures of oppression—in particular, race and class—have interacted in complex ways with gender and sexuality in the history and contemporary challenges of LGBTQ+ representations on-screen, both large and small.

Two profiles take an in-depth look at this theme. In “Giving Voice to Black Gay Men through Marlon Riggs’s Tongues Untied,” Marquis Bey thoughtfully analyzes a canonical film in the archive of Black queer cinema. The 1989 Tongues Untied explicitly addresses, interrogates, and celebrates Black gay identity and culture. Bey also meditates on Riggs’s biography and his relationship to the marginalized voices, Black gay cultural practices, and politics of sexuality within Black communities. In the second profile, “How One Day at a Time Avoids Negative Queer Tropes,” Shyla Saltzman argues that the queer characters of this series are presented in a way that offers nuanced and positive depictions to its queer viewers and allies.

Chapter 11, “LGBTQ+ Literature,” doesn’t try to capture the varied LGBTQ+ literature within a single narrative arc. Instead, Jennifer Miller, the chapter editor, gathered several discussions that explore fields of LGBTQ+ literature: children’s literature, young adult literature, comics, pulp fiction, and memoir. The discussion authors think of literature as both a product and a producer of history. It plays an essential role in the creation of LGBTQ+ culture and the formation of LGBTQ+ communities and identities. Each discussion focuses on tropes, or themes, that emerge in that field. Jennifer Miller’s discussion offers an engaging look at LGBTQ+ children’s picture books as an important source of empowerment for LGBTQ+ youth and families. She traces the history of the LGBTQ+ picture book in the United States and reviews some of the controversies that surround positive imagery of LGBTQ+ life designed for children. The next two discussions explore young adult literature: Maddison Lauren Simmons examines tropes in lesbian young adult literature, and Robert Bittner explores trans and gender nonconforming characters. The last three discussions explore LGBTQ+ comics, by Mycroft Roske and Cathy Corder; lesbian and gay pulp fiction, by Cathy Corder; and LGBTQ+ memoir and life writing by Olivia Wood.

Part VII, “Research,” comprises chapter 12, “A Practical Guide for LGBTQ+ Studies.” The chapter offers practical steps for conducting LGBTQ+ research. In a world where infinite amounts of information appear online, the search for reliable information can be challenging. Rachel Wexelbaum and Gesina Phillips wrote this chapter to help people search for LGBTQ+ information and resources in an effective, mindful manner. They provide tips on what to ask and where to look. This chapter is intended to complement the “Research Resources” sections in the chapters and can support student research assignments in class.

Introduction to LGBTQ+ Studies: A Cross-Disciplinary Approach will acquaint readers with many of the compelling topics found under the broad umbrella of LGBTQ+ studies. Although our intention was to provide global coverage of LGBTQ+ issues, this first edition centers on North America, and particularly the United States. We hope to create a truly global version of this textbook in the future. Nonetheless, we do believe that the textbook you are now viewing on a screen (or holding in your hands) represents a significant contribution to the ever-expanding archive of LGBTQ+ knowledge and literature.

If you plan to use or adapt one or more chapters, please let us know on the Rebus Community platform, and also on our adoption form. Please provide us with feedback or suggestions about the book, and note that we have a separate form for keeping track of issues with digital accessibility.

Last but not least, enjoy!

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project spanned four years, involved several organizations, and called on dozens of contributors. Thanks to everyone who added their work or art or insights; your generosity and talent were inspiring and are very much appreciated.

We are grateful for the help of a few key individuals and organizations whom we would like to acknowledge individually. First, SUNY OER Services provided financial support for this project with funds from New York State’s 2018–2019 budget allocation for Open Educational Resources. The Rebus Foundation, and especially Zoe Wake Hyde and Apurva Ashok, included us in their work on developing resources for the creation of OER textbooks. We learned a great deal about the process of creating OERs and developing textbooks along the way, and we benefited enormously from the resources created by folks at the Rebus Foundation.

Thanks to SUNY Empire State College for supporting our project. This support included a six-month sabbatical for Deborah Amory in the spring of 2019, and a PILLARS grant 2019–2020. We especially recognize Kate Scacchetti, who ably organized the June 2019 workshop in Saratoga for authors; Amanda Mickel, who chased down permissions for us when we thought all was lost; and Meg Benke, provost, who contributed unflagging enthusiasm and unfailing encouragement. Everyone’s help has meant a great deal.

Allison Brown enlisted the help of the SUNY Geneseo student publishing assistants Nicole Callahan and Jack Terwilliger, who helped to make the chapters even more beautiful with openly licensed images and artwork. Thanks as well to Milne Library at SUNY Geneseo for hosting the online, digital OER versions of the textbook.

Some glossary terms in chapters 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 7 are edited versions of definitions found on Wikipedia and Wiktionary and are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License 3.0.

For the SUNY Press edition, we thank Mary Ann Short, who did an awesome job on a developmental edit of the entire text and then copyedited the final stages. Special thanks to Tim Stookesbury, executive director of SUNY Press, who saw the value in this project and supported us in the last two years (2020–2022). Finally, a thousand thanks to Rachel Wexelbaum, our lead librarian and a contributing author, for managing the bevy of librarians who answered the call to develop annotated bibliographies for each and every chapter.

Finally, thanks to everyone who responded to calls for participation and pleas for help in producing two editions of this textbook. Indeed, as Rita Mae Brown once wrote, “An army of lovers shall not fail.” We love this project, and together we have made it happen.

Media Attributions

- Figure I.1. © Deborah Amory is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure I.2. © Deborah Amory is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- "R. Polk Wagner, Information Wants to Be Free: Intellectual Property and the Mythologies of Control,” Columbia Law Review 103 (2003): 995-1034. ↵

- J. Moreau, “Nearly 1 in 5 Young Adults Say They’re Not Straight, Global Survey Finds,” NBC News, June 9, 2021, https://www.nbcnews.com/feature/nbc-out/nearly-1-5-young-adults-say-they-re-not-straight-n12700033. ↵

- Movement Advancement Project, “Hate Crimes,” accessed March 14, 2022, https://www.lgbtmap.org/policy-and-issue-analysis/hate-crimes. ↵

- Rebus Community (website), https://www.rebus.community/; SUNY OER Services (website), https://oer.suny.edu/about-us/; Deborah Amory and Sean Massey, eds., LGBTQ+ Studies: An Open Textbook, beta edition spring 2020, https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-lgbtq-studies/. ↵

- A. Solomon and P. Currah, introduction to Queer Ideas: The David R. Kessler Lectures in Lesbian and Gay Studies (New York: Feminist Press / CUNY Center for Lesbian and Gay Studies, 2003), 3. ↵

- A. Medhurst and S. R. Munt, introduction to Lesbian and Gay Studies: A Critical Introduction, ed. A. Medhurst and S. R. Munt (London: Cassell, 1997), xv; J. Weeks, “The Social Construction of Sexuality: Interview with Jeffrey Weeks,” in Introducing the New Sexuality Studies, ed. S. Seidman, N. Fischer, and C. Meeks (London: Routledge, 2006), 14–20; Solomon and Currah, introduction; S. Stryker, Transgender History: The Roots of Today’s Revolution (New York: Seal Press, 2017). ↵

- “The Combahee River Collective Statement,” in Home Girls: A Black Feminist Anthology, ed. Barbara Smith (New York: Kitchen Table Press), 264–274; and see Combahee River Collective (website), https://combaheerivercollective.weebly.com. ↵

- K. Crenshaw, “The Urgency of Intersectionality,” October 2016, TED Talk, https://www.ted.com/talks/kimberle_crenshaw_the_urgency_of_intersectionality?language=en ↵

- “National Glossary of Terms,” PFLAG, accessed January 11, 2022, https://pflag.org/glossary. ↵

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

name:Deborah P. Amory

Deborah P. Amory is professor of social science at SUNY Empire State College. She holds a PhD from Stanford University in anthropology, and a BA from Yale University in African studies. Her early work focused on same-sex relations on the Swahili-speaking coast of East Africa and on lesbian identity in the United States. She has served in academic administration and has been energized by the open education movement, especially in relation to developing online open educational resource courses and textbooks, including Introduction to Anthropology, Sex and Gender in Global Perspective, and Introduction to LGBTQ+ Studies.