4.2: Pleasure

- Page ID

- 167182

What does the term pleasure mean to you? It’s a good thing right? Embracing embodied living and being present in our mind and bodies in order to tap into our senses. Pleasure, a feeling of happy satisfaction and enjoyment, heals. It is something we live for whether we know it or not. Every human seeks pleasure in one way or another, so why is so much of it taboo in our culture? Let’s unpack this taboo a little bit and then put it away so we can get back to what’s important, pleasure! As we discuss pleasure in general, it is important to note that while all people seek pleasure, we all have varying interest in sexual activity either with others or alone at different points throughout our lives. Sometimes the term Asexual can be used to describe a lack of interest in sexual activity and people who are asexual may self-identify as Ace. Just like gender and sexual orientation, sexual desire can also be viewed as being contained on a spectrum. All people also have desires and seek pleasure; it just may be expressed in ways that differ from how you as an individual define what is pleasurable. The desire for pleasure is universal. Whether it be embodied or in our minds, a connection to our sensual selves helps us tap into this vital piece of our humanity. Sensuality, the notion of being highly tuned into your senses, is an important way to discover what it is you as an individual like. Paying attention to your senses rather than letting standards or norms guide our expressions of gender or sexuality will allow greater satisfaction. Pleasure is deeply connected, but not limited to our sexuality, and sexual health is an important part of overall well-being. The World Health Organization (WHO) considers our sexual health part of our overall quality of life (The World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL), 2012). Whether it be in the form of accessibility to sex education, reproductive rights and health care, or the right to openly express our sexual identity exactly as it is this very moment all add to our quality of life. Having desires and fulfilling them is part of our comprehensive wellness.

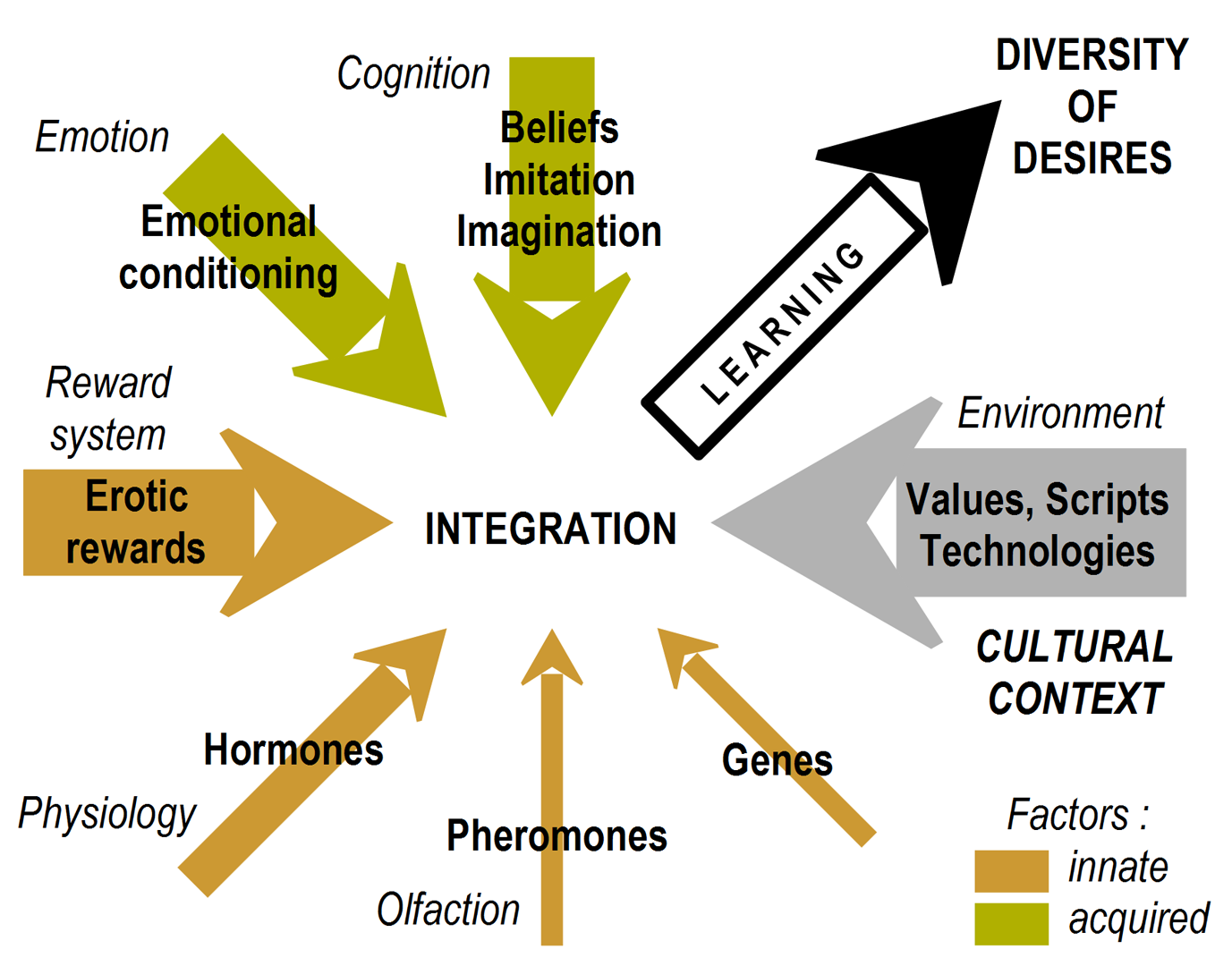

"Learning of the sexual motivation in humans" by Yohan Castel is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

In terms of our sexual gratification, there is a spectrum of what people do to feel good. Whether it be auto-erotic (sexual pleasure with one’s self), or with another person or persons, there is no right way to do it and what feels good to one person may not to another. As long as all parties consent to it, have fun. In many ways consent is complicated rather than a simple yes or no binary as many perceive. The ability to consent replicates the larger social structure. Think about how age, gender, cultural background, body type, race, experiences with trauma and social class afford us different levels of privilege. Consent becomes complicated by all of this. It is complicated by coercion, power, and privilege of those who may or may not consent to something authenticity as a result so a one size fits all definition of consent is difficult. The following clip describes consent in a humorous way. Tea Consent. If consent is to be authentically achieved, there must be open, honest communication and a sense of trust. Consent is ongoing and needs to be revisited. A yes now may be a no in 20 minutes so keep talking. The goal is for consent to be what is known as yes means yes or enthusiastic consent. Flipping this script helps add clarity to what people actually want. Remember, communication is lubrication so communicate about what you like, what you don’t like, and what you want to try. Please also try to let go of societal messaging about how sexuality should look, sound or feel. Getting caught up in cultural standards of beauty or how the act of sex is supposed to look can make us feel like we don’t get to enjoy ourselves until something changes (we lose 5lbs, or learn how to come in a certain position, etc.). The work of Sex Educator, Emily Nagoski influences the ways in which we in this text hope to frame sexuality and self-acceptance. Her 2015 book, Come As You Are, debunks many of the societal messaging around sexuality, gender and offers an empowering alternative.

We all grew up hearing contradictory messages about sex, and so now many of us experience ambivalence about it. That’s normal. The more aware you are of those contradictory messages, the more choice you have about whether to believe them (Nagoski, 2015, p 202).

You are deserving of pleasure right now! You get to define what that pleasure looks like and make choices that you want to make, instead of what you think society values. “When you embrace your sexuality precisely as it is right now, that’s the context that creates the greatest potential for ecstatic pleasure” (Nagoski, 2015 p. 8).

A person who identifies as asexual might be commonly referred to as “Ace” or “Aces”. Asexuality is not defined as abstinence as a result of a bad relationship, celibacy, fear of intimacy, or other commonly referenced stereotypes. Rather, asexuality can be many things, but people who identify as asexual can still fall in love, choose to masturbate, choose to engage in sexual activities, have a spouse or partners(s)! It is important to note that love does not always equal sex, and that sexuality exists on a spectrum. Asexuality, or for that matter, any other sexual identity, is not fixed, nor is it expressed the same for every person who identifies as asexual (Chen, 2020). Asexuality as an orientation is not a single way of orienting towards sex, it is not a catch all, and it can be misinterpreted or misused, so it is best to not apply labels to others, and instead, allow expression and labels to be up to individuals if they chose. For a deeper dive into understanding Asexuality, here are three resources, Yasmin Benoit, Asexuals Need Media Representation, The Amazing Aces. and Season 8, Episode 15 of the Gender Reveal Podcast: Gender Reveal Podcast with Ev'Yan Whitney on the superpower of being an asexual sex educator, which offers first person insight from an asexual sex educator.

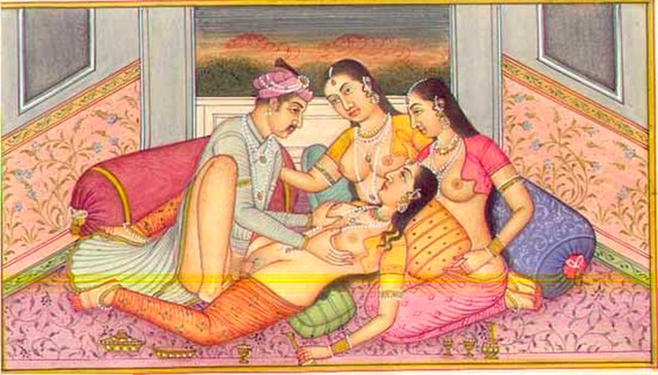

A Guide to Fulfillment: The Kama Sutra

None more famously referenced when talking about pleasure and sexuality is the ancient Sanskrit text, The Kama Sutra. While its actual date of publication is up for debate, it is likely somewhere between 200-400 BCE (Doniger, 2003 p. i). It is a guide to life, in which they include sections regarding sexuality, eroticism, and emotional fulfillment. The Kama Sutra is not exclusively a sex manual on sex positions, although the illustrations have been referenced throughout time as such. Its focus is broader, written as a spiritual manual to the art of living well, the nature of love, finding a life partner, maintaining one's love life, and other aspects pertaining to pleasure-oriented faculties of human life.

The Erotic

“I want to live the rest of my life, however long or short, with as much sweetness as I can decently manage, loving all the people I love, and doing as much as I can of the work I still have to do. I am going to write fire until it comes out of my ears, my eyes, my nose holes--everywhere. Until it's every breath I breathe. I'm going to go out like a fucking meteor!” - Audre Lorde

Audre Lorde (1934-1992), represented many things to many people. Black, poet, womanist, feminist, writer and scholar, and activist whose work included pleasure. Her use of the term Erotic was meant to describe a state of being alive, a feeling one gets when they are tapping into something that provides pleasure. In some cases, the erotic has sexual connotations, but it can also refer to a really good feeling a person experiences when tapping into their joy, like feeling the warm sun on their skin or indulging in something they really like. Lorde pointed out that if we were to really feel deeply and sensually, we would begin to understand what joy we are capable of feeling and live our lives in accordance. Can you imagine?

Stigma: How Culture Constrains Sexual Liberation

It is not hard to understand why we are socialized to not seek pleasure. Religion plays a role in decentering pleasure. Each nation worldwide has a religious foundation that shapes the values and beliefs held. This foundation is the basis for culture. Those raised with religion in their homes may be taught the notion of sin. From an early age, through various agents of socialization like, family, schools, the media and the church, we learn that there is a great deal of stigma surrounding sexual pleasure. As mentioned early on in this book, nations that offer comprehensive and sex-positive sex education from a young age, built intentionally into K-12 curriculum, have lower unintended pregnancy rates and overall comfort levels about communicating about sex. In the United States especially, where White Anglo-Saxon Protestant (WASP) ethics shape culture, this is not the case. Instead, the focus is more about denying pleasure and shaming sexuality. Lust, a strong passion or longing for something especially related to sexual desire, is one of the seven deadly sins written about in the Christian Bible. Masturbation is labeled a sinful act, and when young children are “caught” exploring their bodies, they are often shamed for it. Rather than seeing the moment as an opportunity to educate our kids about their bodies, parents usually mishandle the opportunity, and kids come away from the experience feeling like sexual pleasure is something they should hide and be ashamed of. This cultural message about sexual pleasure gets internalized at a very young age, and we quickly learn that sex is something that we are not supposed to talk about and depending on our gender identity, we are also not supposed to ask for it, desire it, or be in charge of it, unless we are trying to procreate. Those gendered female and non-binary are not usually allowed to initiate sex, want sex, or control the act of sex. Our bodies are seen as something to be ashamed of. Medieval anatomists called female external genitalia the pudendum which is derived from the Latin, pudere, meaning to make ashamed (Nagoski, 2015, p 18). Hysteria, another Latin term commonly used to describe exaggerated or uncontrollable emotion or excitement, literally translates to uterus. And then we have hedonism, the belief that pleasure is the most important thing in life which is derived from the Greek word, delight. Society often juxtaposes hedonism, the pursuit of pleasure or sensual self-indulgence, with discipline and inhibiting one’s desires, and devalues the notion that as humans we deserve the right to follow our desires.

"Shame" by Libertinus Yomango is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

In U.S. culture hard work, material gain, and goal achievement are values that supersede personal desire. Pleasure is not quantifiable in the capitalist sense, and so it becomes more of an extra than something we espouse as a necessity. As a result, we receive mixed messages about sex, pleasure and fulfillment. Knowing that there is a cultural hang up with accessing pleasure can help us navigate the messy waters of sexuality and society and inform our decisions. Understanding this contradiction gives us the ability to question and debunk myths around pleasure, self-care and overall well-being. Hang-ups about our bodies or what we like sexually are entirely shaped by culture, and the sooner we move past self-criticism into self-love, the better. The ability to enjoy your sexuality in this very moment rests on what you are telling yourself about yourself.

You, too, are healthy and normal at the start of your sexual development, as you grow, and as you bear the fruits of living with confidence and joy inside your body. You are healthy when you need lots of sun, and you’re healthy when you enjoy some shade. That’s the true story. We are all the same. We are all different. We are all normal (Nagoski, 2015 pp. 7).

Sometimes the confines of culture clouds our ability to love ourselves exactly how we are. We may also experience trauma related to our sexuality that needs to be processed in order to get to a place of radical self-acceptance. In any case, recognize the power to embrace yourself just as you are and enjoy life, whether that be through your sexuality or in any other realms that you derive pleasure from. We all deserve the right to feel good. Playwright Eve Ensler, in The Vagina Monologues, famously asks her audience what the world would look like with a bunch of “happy vaginas coming all the time” (Ensler, 1996). A world full of people who took care of their pleasure as a regular part of their overall wellness would look very different than the one we currently live in. Undoing all the cultural “no’s” we've been told is not easy, and those “no’s” may have prevented us from learning more about our amazing pleasure seeking selves. A really good resource for questions about sexuality and tapping into desire is, Meet Lindsey Doe! - Welcome to Sexplanations - 1. Check it out!

As you read that last section, what is coming up for you? Are you buying it? Do you deserve to feel pleasure? If not, stop and ask yourself why. Quickly rule out that “why”, and move along to what it is you desire. Tap into the Erotic. Make a list of 5 things that bring you joy. Any kind of joy. Put it somewhere you can see. Each day try to give yourself at least one of those things. More is always better so extra credit if you can give yourself all five.

Pleasure and Social Justice

What does agency over one's body mean exactly? It seems pretty straightforward and is something we imagine all humans have a right to. Historical legacies of colonization, slavery, imprisonment, sexism and homophobia diminish agency for those impacted by these injustices. The impacts of these are still there for many, and so it begs the question, what does pleasure look like if you are navigating a world that constantly has a target on your back?

These impacts are felt more severely for already marginalized groups particularly because of this historical legacy. For Black women and girls in particular, their physical bodies have always been used as a way to maintain a racial hierarchy long after emancipation and the end of Jim Crow segregation. There is a highly racist stereotype that paints them as inherently sexual and innately promiscuous. A 2017 Georgetown University study found that,

Black girls as young as 5 years old are already seen as less innocent and in need of less support than white girls of the same age. This presumption leads teachers and other authority figures to treat Black girls as older than they actually are and more harshly than white female students, with the disparity being particularly wide for 10-to 14-year-olds (Epstein et al, 2017).

From a young age then, these types of inappropriate attributions leave Black women and girls at a disadvantage. Based on nothing more than ignorance, this myth removes agency and inappropriately sexualizes young children. As indicated in this study, a perception of an individual's sexuality is something that has farther reaching consequences than access to pleasure. Sometimes, as in the case of Black women and girls, their bodies are weaponized against them, diminishing overall life satisfaction and opportunity.

Those who create these falsehoods and myths and present them as facts are unfortunately often the same experts we rely on to help guide us in our understanding of human sexuality. Prominent sex educators make assertions about sexuality, health, and normalcy from a very specific frame. Overwhelmingly, sex researchers tend to be cis gendered, white, heterosexual, and male, and may or may not have an understanding of the diversity inherent in human sexuality. Yet these are the people defining cultural standards of what are normative sexual attitudes or behavior. Not everyone identifies with these standards. Even as this book is being written, it is important to note that it is situated in a specific time and place. Although here we undertake a cultural critique of the narrow definition of “normal” sexuality, this too will shift as time passes. As the field of sex educators becomes more diverse and representative of the many demographics present in the culture, the understanding will widen to be more inclusive and more accurate.

I’ve spent the majority of my adult life participating in hookup culture, and until recently, I did not experience any issues with regard to pleasure, sexual arousal and sexual responses. When I reached my mid-twenties, I developed a realization that I did not enjoy sex as much as I did in my early years as an adult, and it became more difficult to become aroused. Hookup apps like Grindr, Tinder, and other web-based services can allow users to experience sexual freedom, however, can be addictive, and (as it relates to me) might alter the user’s ability to engage in intimacy due to the anonymous nature of sex apps.

I began using Grindr as a recently single twenty year old with limited sexual experiences and almost no dating history. As I became more familiar with Grindr, I began using the app for what most people believe to be its purpose, which is sex. After a few years, I began dating men and realized I was experiencing difficulties reaching orgasms with the people I dated. Once I would break up with my partner, I would quickly get back on the Grindr train and would be able to easily experience orgasms. After a few cycles of dating people, breaking up with them, and heading back to the world of anonymous sex, I realized that the use of hookup apps distorted the ways in which I was able to experience sexual pleasure.

As an adult in my mid-twenties, I’ve become more intentional about my choices of sexual partners, because personally, I do not like to separate sexual pleasure and intimacy.