14.6: Rape

- Page ID

- 167989

Rape is a type of sexual assault, usually involving sexual intercourse or other forms of sexual penetration carried out without that person’s consent. Information here about the extent and nature of rape and reasons for it comes from three sources: the FBI Uniform Crime Reports and the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS), and surveys of and interviews with women and men conducted by academic researchers. From these sources, we will provide information about how much rape occurs, the context in which it occurs, and the reasons for it.

What do we know about rape?

About 20%–30% of women college students in anonymous surveys report being raped or sexually assaulted (including attempts), usually by a male student they knew beforehand (Fisher, et al, 2000; Gross, et al, 2006). Thus, at a campus of 10,000 students, of whom 5,000 are women, about 1,000–1,500 will be raped or sexually assaulted over a period of 4 years, or about 10 per week in a 4-year academic calendar.

The public image of rape is of the proverbial stranger attacking someone in an alleyway. While such rapes do occur, most rapes actually happen between people who know each other. A wide body of research finds that 60%–80% of all rapes and sexual assaults are committed by someone the person knows, including ex-spouses and only 20%–35% by strangers (Barkan, 2012). Barkan, S. E. (2012). Criminology: A sociological understanding (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. A person is thus two to four times more likely to be raped by someone they knows than by a stranger.

Sociological explanations of rape fall into cultural and structural categories. Various “rape myths” in our culture support the absurd notion that women somehow enjoy being raped, want to be raped, or are “asking for it” (Franiuk, et al., 2008). One of the most famous scenes in movie history occurs in the classic film Gone with the Wind, when Rhett Butler carries a struggling Scarlett O’Hara up the stairs. She is struggling because she does not want to have sex with him. The next scene shows Scarlett waking up the next morning with a satisfied, loving look on her face. The not-so-subtle message is that she enjoyed being raped or that she changed her mind and therefore women may need a little coercion to be convinced..

A related cultural belief is that women somehow ask or deserve to be raped by the way they dress or behave. If she dresses attractively or walks into a bar by herself, she wants to have sex, and if a rape occurs, well, then, what did she expect? In the award-winning film The Accused, based on a true story, actress Jodie Foster plays a woman who was raped by several men on top of a pool table in a bar. The film recounts how members of the public questioned why she was in the bar by herself if she did not want to have sex. They ultimately blamed her for being raped.

A third cultural belief is that a man who is sexually active with a lot of women is a stud. Although this belief is less common presently, it is still with us. A man with multiple sex partners continues to be the source of envy among many of his peers. At a minimum, men are still the ones who have to “make the first move,” and then continue making more moves. There is a thin line between being sexually assertive and sexually aggressive (Kassing et al, 2005). Gender role conflict, homophobia, age, and education are seen as predictors of male rape myth acceptance. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 27(4), 311–328.

These three cultural beliefs—that women enjoy being forced to have sex, that they ask or deserve to be raped, and that men should be sexually assertive or even aggressive—combine to produce a cultural recipe for rape. Although most men do not rape, the cultural beliefs and myths just described help account for the rapes that do occur. Recognizing this, the contemporary women’s movement began attacking these myths back in the 1970s, and the public is much more conscious of the true nature of rape than a generation ago. That said, much of the public still accepts these cultural beliefs and myths, and prosecutors continue to find it difficult to win jury convictions in rape trials unless the woman who was raped had suffered visible injuries, had not known the man who raped her, and/or was not dressed attractively (Levine, 2006). Racism also factors into rape trial outcomes. For instance, when the victim is white and the accused is Black, the chance of conviction is much higher than in the reverse situation, or if both were either white or Back. This speaks to the larger issue of racism in our criminal justice system.

Structural explanations for rape emphasize the power differences between women and men. In societies that are male-dominated, rape and other violence against women is a likely outcome, as they allow men to demonstrate and maintain their power over women. Supporting this view, studies of preindustrial societies and of the 50 states of the United States find that rape is more common in societies where women have less economic and political power (Baron & Straus, 1989; Sanday, 1981). Poverty is also a predictor of rape: although rape in the United States transcends social class boundaries, it does seem more common among poorer segments of the population than among wealthier segments, as is true for other types of violence (Rand, 2009). Some scholars have postulated that the higher rape rates among the poor stem from poor men who have been emasculated by the capitalist system trying to prove their “masculinity” by taking out their economic frustration on women (Martin, Vieraitis, & Britto, 2006).Approximately 4 out of 5 rapes are committed by someone known to the survivor.

- 82 percent of sexual assaults are perpetrated by a non-stranger.

- 47 percent of rapists are a friend or an acquaintance.

- 25 percent are an intimate partner.

- 5 percent are a relative.

Below are some devastating statistics that speak to the magnitude of sexual violence:

- Every 68 seconds an American is sexually assaulted

- The majority of victims are under 30 years old

- 1 out of every 6 American women have been the victim of an attempted or completed rape in her lifetime

- About 3% of American men—or 1 in 33—have experienced an attempted or completed rape in their lifetime

- 1 out of every 10 rape victims are male

- 21% of TGQN (transgender, genderqueer, nonconforming) college students have been sexually assaulted, compared to 18% of non-TGQN females, and 4% of non-TGQN males

- American Indians are twice as likely to experience a rape/sexual assault compared to all races.

- 6,053 military members reported experiencing sexual assault during military service in FY 2018. DoD estimates about 20,500 service members experienced sexual assault that year (Victims of Sexual Violence, n.d.).

For further in-depth statistics, please visit Victims of Sexual Violence: Statistics | RAINN

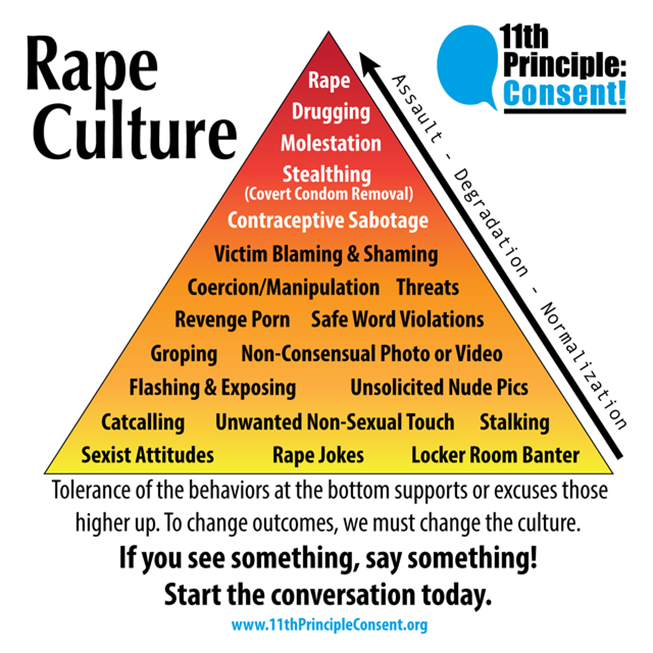

Rape Culture

Gender role stereotyping often conflates being a man with being violent. The myth of heterosexual sex as a conquest or an adversarial interaction sets the stage for coercion and lack of consent. An acceptance of violence in interpersonal relationships help create a climate that encourages many types of violence, including rape. By following a social script that asks males to be tough and dominant, young men learn that it’s okay to control women. Rape culture normalizes, trivializes, and denies rape and blames, slut-shames, and dismisses the pain of survivors. As a result of this, survivors are often hesitant to come forward. It is estimated that anywhere from 60-80% of rapes go unreported, making it the most under-reported crime (National Sexual Violence Resource Center, 2018). When survivors come forward, they risk social and psychological consequences such as re-traumatization and victim blaming. In The Opposite of Rape Culture is Nurturance Culture published in 2016 Nora Samaran writes “Survivors are punished from all sides. People cut ties with them, shame them, and force them to relive the experience over and over while doubting and questioning them on every point” (Samaran, 2016).

Responses to rape culture have involved decriminalizing assaults, since many see the criminal justice system as non-consensual, racially biased and ineffective. An eye for an eye has done so much collateral damage. People who are hurt may want those who hurt them to take accountability for what they did, and restorative justice can be an alternative that allows for such accountability.

In other efforts to call out rape culture and slut shaming, slut walks have been marches designed to combat the stigma surrounding women and sexuality. The first slut walk took place in 2011 in Toronto, Canada. The marches are usually made up of young women, often wearing clothes considered to be “slutty.” Slutwalks around the world take a variety of forms; sometimes there are speaker meetings and workshops, live music, sign-making sessions, leafleting, open microphones, chanting, dances, martial arts, and receptions or after-parties. Oftentimes, survivors speak of their assaults for the first time at events such as these.

"Date Rape Drugs"

One of the great things about being in college is having the chance to meet and get to know so many new people. Sadly, through this process many students are sexually assaulted. The National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) found that approximately 1 in 4 college women will be sexually assaulted while in school. One very real risk on college campuses—and elsewhere—is the use of date rape drugs in order to commit sexual assaults. Date rape drugs are powerful and dangerous drugs that can be slipped into your drink when you are not looking. The drugs often have no color, smell, or taste, so you can’t tell if you are being drugged. The drugs can make you become weak and confused—or even pass out—so that you are unable to refuse sex or defend yourself. If you are drugged, you might not remember what happened while you were drugged. Date rape drugs are used on anyone regardless of gender. There are now a variety of test strip products on the market that can identify their presence. Some colleges have begun offering these products free to students, along with suggested practices to keep yourself safe.

The three most common date rape drugs are Rohypnol, GHB, and Ketamine:

- Rohypnol comes as a pill that dissolves in liquids. Some are small, round, and white. Newer pills are oval and green-gray in color. When slipped into a drink, a dye in these new pills makes clear liquids turn bright blue and dark drinks turn cloudy. But this color change might be hard to see in a dark drink, like cola or dark beer, or in a dark room. Also, the pills with no dye are still available. The pills may be ground up into a powder.

- GHB has a few forms: a liquid with no odor or color, white powder, and pill. It might give your drink a slightly salty taste. Mixing it with a sweet drink, such as fruit juice, can mask the salty taste.

- Ketamine comes as a liquid and a white powder.

These drugs also are known as “club drugs” because they tend to be used at dance clubs, concerts, and “raves.” The term “date rape” is widely used to describe sexual crimes involving these drugs, but most experts prefer the term “drug-facilitated sexual assault.” These drugs are also used to help people commit other crimes, like robbery and physical assault. The term “date rape” can be misleading, because the person who commits the crime might not be dating the victim. Rather, it could be an acquaintance or stranger.

Alcohol and Other Drugs

Alcohol is also a drug that’s commonly used to help commit sexual assault. Be aware of the risks you take by drinking alcohol at parties or in other social situations. When a person drinks too much alcohol:

- It’s harder to think clearly.

- It’s harder to set limits and make the same choices you would if you were sober.

- It’s harder to tell when a situation could be dangerous.

- It’s harder to say “no” to sexual advances.

- It’s harder to fight back if a sexual assault occurs.

- It’s possible to blackout and have memory loss.

The club drug “ecstasy” (MDMA) has been used to commit sexual assault. It can be slipped into someone’s drink without the person’s knowledge. Also, a person who willingly takes ecstasy is at greater risk of sexual assault. Ecstasy can make a person feel “lovey-dovey” toward others. As with alcohol, it also can lower a person’s ability to give consent. Once under the drug’s influence, a person is less able to sense danger, or to resist a sexual assault.

Even if a survivor of sexual assault drank alcohol or willingly took drugs, that person is not at fault for being assaulted. You cannot “ask for it” or cause it to happen. Still, it’s important to be vigilant and take precautionary steps to avoid putting yourself at risk. Some ways to protect yourself:

- Don’t accept drinks from other people.

- Open containers yourself.

- Keep your drink with you at all times, even when you go to the bathroom.

- Don’t share drinks.

- Don’t drink from punch bowls or other common, open containers. They may already have drugs in them.

- If someone offers to get you a drink from a bar or at a party, go with the person to order your drink. Watch the drink being poured and carry it yourself.

- Don’t drink anything that tastes or smells strange. Remember, GHB sometimes tastes salty.

- Have a non-drinking friend with you to make sure nothing happens.

- If you realize you left your drink unattended, pour it out.

- If you feel drunk and haven’t drunk any alcohol—or, if you feel like the effects of drinking alcohol are stronger than usual—get help right away.

How and Where to Get Help

If you or someone you know has been assaulted, it’s important to get help immediately. No one should suffer in silence and if you are planning to take legal action, time is of the essence in terms of gathering evidence. Take the following steps if you or someone you know has been raped, or you think you might have been drugged and raped:

- Get medical care right away. Call 911 or have a trusted friend take you to a hospital emergency room. Don’t urinate, douche, bathe, brush your teeth, wash your hands, change clothes, or eat or drink before you go. These things may give evidence of the rape. The hospital will use a “rape kit” to collect evidence.

- Call the police from the hospital. Tell the police exactly what you remember. Be honest about all your activities. Remember, nothing you did—including drinking alcohol or doing drugs—can justify rape.

- Ask the hospital to take a urine (pee) sample that can be used to test for date rape drugs. The drugs leave your system quickly. Rohypnol stays in the body for several hours and can be detected in the urine up to 72 hours after taking it. GHB leaves the body in 12 hours. Don’t urinate before going to the hospital.

- Don’t pick up or clean up where you think the assault might have occurred. There could be evidence left behind—such as on a drinking glass or bed sheets.

- Get counseling and treatment. Feelings of shame, guilt, fear, and shock are normal. A counselor can help you work through these emotions and begin the healing process. Calling a crisis center or a hotline is a good place to start. One national hotline is the National Sexual Assault Hotline at 800-656-HOPE. (Sexual Assault, 2020).