1.1: Introduction

- Page ID

- 21955

This chapter focuses on understanding the role and processes of urbanization in the context of BC. In particular, it emphasizes recent understandings of urban sustainability and urban systems thinking. The primary goal, on finishing this chapter, is to have an understanding of the relationality and territoriality of cities; that is, understanding how cities exist in what geographer Doreen Massey calls a “global sense of place.” This will connect with the second goal of the chapter, which is to understand how cities are related to other places, and how cities are at the same time unique places. The concept of a global sense of place has three characteristics:

- Places have multiple identities and meanings. The meaning is dependent on the people who are experiencing a place.

- Places are more than physical locations; they are made up of processes.

- Places are not static, they are ongoing and ever changing because of relationships to other places.

A global sense of place means viewing every city as globalized or worldly precisely because of its relationship to other places, and the mobile processes that are ongoing in places. Likewise, a global sense of place means that the territoriality, or what makes a place unique, can be understood because other places are different.

Cities

A city, in its most basic sense, is a constellation of people and social, political and economic institutions and infrastructures within a physical location. While there is usually no agreed-upon population or socio-economic configuration for most cities, they are nevertheless understood to be discrete locations that are governed by political institutions (e.g., a municipal government with a mayor and city council), and city governments have the power to make laws and collect taxes from the people and businesses that inhabit it. Cities of course, do not exist in isolation from other places. They are connected to places near and far, to other cities and to rural communities and landscapes.

Cities are created through processes of urbanization, which combine various socio-economic, political, technological, and environmental processes that affect the way that cities are made up and how people live in them.

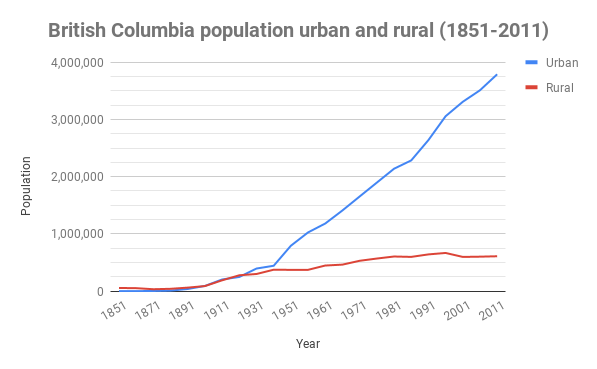

In British Columbia in 2011, there were 49 municipalities designated as cities, with an average population of 59,716 (Census data). The current (2014) total population of BC is 4,606,375, and 2,926,102 of those people live in cities. With more and more people moving to to cities within the province, we can ascertain that BC is undergoing a process of urbanization.

Processes that make up cities

Some of the processes that make up cities and contribute to this global sense of place are economic change, demographic change, political change, sociocultural change, technological change and environmental change. As well, local histories and physical landscapes contribute to the uniqueness and differences in cities.

Economic changes are often dynamic and exist on many scales. An economic change may be, for example, the shift from a subsistence-based economy to one of pre-capitalist trade or, in contemporary society, a shift in the form of capitalist accumulation. Cities, as sites of resource agglomeration, are key actors within the network of global economic activity. Cities gather, regulate, produce and redistribute capital in the form of physical resources, money and human labour. As well, cities have their own regional and local economies that are connected to broader economic flows.

Within cities, as well as among cities, capital is unevenly distributed between people, which causes shifting demographic, political and sociocultural changes.

Demographic changes, such as the size, composition and speed of change profoundly affect urban landscapes. For example, in 2011, the city of Surrey was the fastest growing city in Canada. With its large and growing East Asian population, it is also emerging as a multicultural hub within the province, and at the same time it is a place characterized by a growing local economy and a mild climate, placing it as an affordable alternative to Vancouver or Victoria.

Political change at various scales (international, federal, provincial and municipal) also has important effects on cities. Governments have the power to levy taxes and to redistribute resources. They make laws that regulate everything from environmental and economic activity to managing migration. Shifts in political agendas can mean the difference between securing funding for a local health authority versus public transit in the region.

Sociocultural changes affect everything from architectural style to the kinds of amenities that are provided in cities. For example, BC is known for its natural beauty, so cities often highlight local access to outdoor activities such as hiking, skiing or cycling. Sociocultural change is broader than physical attributes, however. Behaviour toward minority groups has also altered drastically within cities over the years. For example, from 1859 to 1923, Canada levied the Chinese head tax, a fee charged to each Chinese person entering Canada. It was abolished in 1923 by the Chinese Immigration Act, which prohibited immigration from China to Canada. Many years later, in 2006, the federal government offered an official apology and financial remuneration to survivors and their spouses who paid the head tax.

Another example of changing attitudes is evident in the story of the Indian residential school system, which was in place from the 1880s until 1996. During much of that time, Aboriginal children were required to attend government- and church-run schools under an ideology of assimilation. There was widespread physical, sexual and mental abuse within the schools, which also separated Aboriginal children from their families and their land. The increasing urbanization of Aboriginal people in BC and in Canada is also attributed to the residential school system. In 2008, the federal government apologized for how Aboriginal people were treated under the system.

Technological changes affect the physical environment and how people live in cities. Economic innovation is often precipitated by technological change. For example, the development of the steam engine was strong enough to power a long-distance railway across much of North America. Today, advances in telecommunications and wireless networks allow people in cities to carry devices that allow mobile Internet access. Cities have also become tech hubs, providing jobs to local economies. For example, Vancouver is the home to HootSuite[1] and Electronic Arts Entertainment. [2]

Environmental changes that affect cities tie into broad networks. For example, air pollution and water quality cannot be governed or contained at the local level; they require cross-jurisdictional management. Increasing CO2 emissions not only raise local health risks in cities, causing higher rates of asthma and other respiratory illness, but also contribute to global climate change.

Understanding the interrelationship of these various urbanization processes helps us to understand the dynamic role of cities.

Attributions

- Figure 1.1 Graph of BC’s population from 1851-2011. British Columbia population, urban and rural (1851-2011) by Arthur Gill Green. Adapted from Population, urban and rural, by province and territory (British Columbia), Statistics Canada.

- Figure 1.2 Residential schoolchildren. St. Paul’s Indian Industrial School, Middlechurch, Manitoba, 1901 is in the Public Domain Retrieved from http://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Canadian_Indian_residential_school_system#mediaviewer/File:Stpauls-middlechurch-man.jpg)

- HootSuite https://hootsuite.com/↵

- Electronic Arts Entertainment http://www.ea.com/ca↵