4.6: Chapter 30- Impeachment and Removal of the President

- Page ID

- 73471

Impeachment Power

The founders were very familiar with impeachment in British and Colonial American history. Beginning in 1376, the House of Commons “prosecuted powerful offenders before the House of Lords.” (4) Frequently, this process—called impeachment, a term with which American colonists were very familiar—involved executive ministers and was a way for Parliament members to exert influence over the Crown by proxy. Even though the British monarch could not be impeached, the House of Commons proclaimed that impeachment was a principal instrument to hold royal power accountable. In the American colonies—particularly after 1755 and then intensifying in the 1770s—colonial assemblies “came to see impeachment as the mechanism by which the people could begin the process of ousting official wrongdoers, understood as those who betrayed republican principles, above all by abusing their authority through corruption or misusing power.” (5) After independence, several states put impeachment provisions in their state constitutions.

The founders created an impeachment provision in the U.S. Constitution and were anxious that it be applied to any future president who had, in the words of Benjamin Franklin, “rendered himself obnoxious” to the Constitutional order and the rule of law. The president, vice president, and other civil U.S. officers can be removed from office by Congress if they are found guilty of “treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.” While the definitions of treason and bribery are clear, the phrase “other high crimes and misdemeanors” sometimes confuses people. However, the founders were quite clear about what they meant. George Mason originally proposed that the House be able to impeach in cases of treason, bribery, or “maladministration,” but that was deemed to be too broad a term. Instead, they chose the phrase “or other high crimes and misdemeanors,” which had precedent in English law going back to 1642. What did they mean by that odd phrase? They were particularly concerned about presidents who fraudulently achieved office, who might be under the influence of—or conspire with—foreign powers, who improperly enriched themselves, who undermined the rule of law, or who became incapacitated. (6) As put by constitutional scholars Lawrence Tribe and Joshua Matz, “In creating the impeachment power, the Framers worried most of all about election fraud, bribery, traitorous acts, and foreign intrusion. Willful conspiracy with a hostile foreign power to influence the outcome of a presidential election directly evokes all of these concerns.” (7) It is clear that the president’s offenses need not be law violations and could instead be technically legal assaults against the common good or the public trust. For example, Alan Hirsch argues that it is perfectly legal for a president to pardon all members of his own party for any federal offenses, but such action would be reasonable grounds to impeach and remove that president. (8)

The impeachment process is a fairly straightforward one, albeit one full of political dangers for everyone involved. At its most basic, constitutionally removing a president is a two-step process: The House impeaches and the Senate holds a trial to either remove the president or allow them to stay in office. Let’s suppose the president is accused of committing a criminal act, abusing their office, or undermining the rule of law. The impeachment process begins in the House of Representatives, where one or more members introduces a bill to impeach. This bill will be referred to the House Judiciary Committee, which will hold hearings and vote whether to report out articles of impeachment to the full House. Other relevant House committees may hold hearings as well. Articles of impeachment are essentially the specific charges against the president. The full House debates the articles of impeachment and votes; a successful majority vote on one of the charges means that the president has been impeached. Then the process moves to the Senate, where the president is put on trial and the senators determine whether the president is “guilty” of the offenses spelled out in the articles of impeachment. Members of the House Judiciary Committee come over to the Senate to present the case against the president, while the president’s lawyers mount a defense. The Chief Justice of the Supreme Court comes into the Senate to preside over the trial. The Constitution requires a two-thirds vote in the Senate to convict and remove the president.

Congress has never gone through the whole process and successfully removed a sitting president. However, there have been four notable cases in American history that you should know:

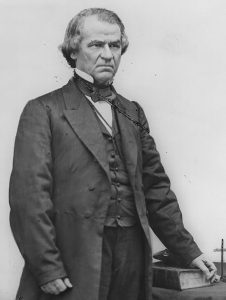

Andrew Johnson

In the 1864 presidential election, Republican Abraham Lincoln chose Tennessean and Democrat Andrew Johnson as his running mate in an effort to reach out to Democrats who supported the Union’s war effort. The Lincoln-Johnson ticket won. John Wilkes Booth shot President Lincoln on April 14, 1865, and Lincoln died the next morning. Andrew Johnson became president at a time when members of the Republican Party’s radical wing were adamant that the defeated Southern states be “reconstructed” into loyal Union members and that African Americans be guaranteed political rights and full participation. Johnson was more inclined to be lenient with the former Confederate states, which included his home state of Tennessee. Indeed, he did not believe that Blacks were capable of democratic governance and said in 1865 that “White men alone must manage the South.” (9) He vetoed the 1866 Civil Rights Act and the Freedmen’s Bureau bill, which was designed to enlarge and solidify the powers of the already existing Freedmen’s Bureau to protect the civil rights and liberties of newly freed slaves and refugees. This angered the Radical Republicans, and Congress overrode his vetoes. Johnson also opposed passing the Fourteenth Amendment, which granted former slaves citizenship. It passed anyway.

To limit Johnson’s power, Congress passed the Tenure of Office Act in 1867, which said that the president could not remove the holders of any appointed positions unless the Senate concurred. When Johnson removed Secretary of War Edwin Stanton without the Senate’s approval and replaced him with Lorenzo Thomas, the House voted to impeach him for the clear violation of the Tenure of Office Act. They also impeached him for very derogatory statements he made about Congress, specifically that he “did attempt to bring into disgrace, ridicule, hatred, contempt and reproach to the Congress of the United States.” That’s not a crime, although they impeached him for it anyway. After a three-month trial in 1868, President Johnson’s opponents came one vote short of a two-thirds majority to remove him from office. He served out the remainder of his term. Interestingly, the Tenure of Office Act was repealed in 1887, and then the Supreme Court definitively ruled in Meyers v. United States (1926) that the president does not need Senate approval to fire executive branch officials.

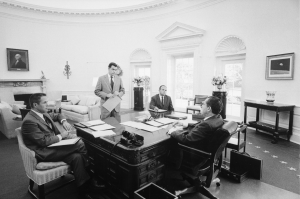

Richard Nixon

On June 17, 1972, agents of President Richard Nixon’s Committee for the Re-Election of the President (CREEP) were caught breaking into the Democratic Headquarters in the Watergate office and residential complex. Nixon immediately tried to cover up the incident by ordering hush money payments and telling the Federal Bureau of Investigation to not look into it. The cover-up ultimately did not work, and the revelations that followed constituted a shock to the American public that reverberated for decades. Nixon did everything he could to forestall the inevitable. In the famous Saturday Night Massacre, Nixon ordered Attorney General Elliot Richardson to fire Archibald Cox, who was serving as the independent special prosecutor in the case. Richardson resigned rather than carry out the order. Nixon then ordered Deputy Attorney General William Ruckelshaus to fire Cox. Ruckelshaus also refused to do it and resigned instead. Then Nixon asked Solicitor General Robert Bork to fire Cox, and Bork complied.

The scandal that started with the Watergate break-in expanded to reveal shocking corruption in the Nixon administration. Nixon and his subordinates were responsible for, among other things, extorting money from rich individuals and corporations; spying on American citizens because they disagreed with the president’s policies; trying to use the Internal Revenue Service to destroy “enemies” of the president; selling government favors in exchange for campaign contributions; seriously contemplating the murder of a journalist; and breaking into psychiatrists’ offices looking for dirt on opponents. (10)

Nixon had a taping system in the White House that recorded his conversations with everyone who came into his office. Nixon refused to turn over the tapes in the face of a congressional subpoena until forced by a unanimous Supreme Court decision. The case, The United States v. Nixon (1974), established that while the president had the right to confidentially record conversations with his advisors, executive privilege did not extend to refusing to turn over records pertinent to a criminal proceeding. Apparently, Nixon contemplated refusing to turn over the tapes and pardoning the burglers and those in his administration who had already been convicted and indicted, but in the end decided to comply with the Supreme Court’s order. (11) The tapes revealed the cover-up’s “smoking gun”: Nixon suggested to his chief of staff that the FBI be told by the CIA to stay out of the Watergate investigation because it dealt with national security issues—an assertion that was not true and that clearly indicated obstruction of justice. Nixon resigned the presidency on August 9, 1974, just before the full House had a chance to vote on accepting three articles of impeachment. By resigning before he was actually impeached by the House, Nixon was then eligible to be pardoned by Gerald Ford, who assumed the presidency after Nixon’s resignation.

Bill Clinton

The House of Representatives voted along party lines in 1998 to impeach President Bill Clinton in what is surely the most sensational sexual, political scandal ever to hit the American presidency. The complicated story can be distilled as follows: While he was still governor of Arkansas, Clinton allegedly dropped his pants and propositioned an Arkansas state employee named Paula Jones in a Little Rock hotel. With support from conservatives, including lawyer Kenneth Starr, Jones pursued a sexual harassment lawsuit against now President Clinton. Kenneth Starr later became the independent counsel charged with investigating a variety of non-sexual allegations against Clinton and his wife. Starr eventually failed to find enough evidence that the Clinton’s ever did anything impeachable in their finances or in running the White House.

However, during depositions in the Paula Jones case designed to demonstrate Clinton’s pattern of sexual harassment, the president was asked whether he had had “sexual relations” with Monica Lewinsky, a former White House intern. She was asked a similar question. Clinton and Miss Lewinsky both said in their depositions that they had not had sexual relations, when in fact they had. Independent Counsel Starr heard about this from Paula Jones’ lawyers and went to Attorney General Janet Reno to get his investigative mandate extended to cover this salacious affair. The Attorney General agreed to grant Starr’s request, although Starr allegedly hid from Reno the fact that he had an obvious conflict of interest in this case. (12) Both Clinton and Lewinsky were brought before Starr’s grand jury to testify, and they again stated that they did not have sexual relations. In the meantime, the president’s secretary recovered gifts Clinton had given Lewinsky, and the president repeated his lies to his associates, knowing that they would restate them in their testimony before the grand jury. The Independent Counsel’s report indicated that Clinton and Lewinsky had ten “sexual encounters” short of actual intercourse. (13)

The House passed two articles of impeachment against Clinton that centered on his perjury under oath and his obstruction of justice by encouraging others to perjure and conceal evidence. The case’s facts were not really in dispute: Clinton did what the House alleged. When the impeachment case reached the Senate, Clinton survived by a comfortable margin, with only fifty of the required sixty-seven senators voting to convict. Very few people outside of the president’s staunchest political allies argued that Clinton’s testimony did not constitute perjury—he clearly gave false statements under oath in a federal case. The debate in the Clinton impeachment revolved around two issues: 1) Did lying under oath in court about an embarrassing extramarital affair constitute a serious enough offense to remove the president? and 2) How much damage did the Clinton scandal—with its salacious details—do to the presidency’s moral authority? In the end, the broad national consensus was that Republican efforts to impeach and remove Clinton amounted to an overly moralistic and politically opportunistic overreaction to a scandal that in no way threatened the Constitutional order.

Donald Trump

In hindsight, it should not have surprised anyone that Donald Trump became the third president to be impeached by the House of Representatives. As a businessman who inherited wealth from a father who flouted the law, Trump’s conduct before taking up his position in the White House allegedly included tax fraud, running a fraudulent foundation, running a fraudulent university, bilking subcontractors, posing as a publicist and praising himself to a reporter, and engaging in sexual harassment and assault. (14) During the 2016 campaign, Trump flouted post-Nixon custom and refused to release his tax returns. He also paid off at least two women to keep their adulterous sex stories out of the news during the campaign.

Once in office, President Trump engaged in numerous potentially impeachable offenses that included violating the Constitution’s emoluments clause by accepting money from foreign governments; obstructing justice by firing FBI Director James Comey when he opened up an investigation into Russian ties to the Trump campaign; obstructing justice with respect to Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s Russian ties to the Trump campaign investigation; violating his duty to see that laws are executed by advocating violence perpetrated by various supporters and law enforcement personnel; abusing his pardon power in the cases of Joe Arpaio and the pardons for war crimes, thereby undermining the rule of law; committing crimes against humanity for separating children from their parents at the U.S. border, placing them in inhumane conditions and having no plan to reunite them when their cases were adjudicated; and violating campaign finance laws while he was president by reimbursing his personal lawyer Michael Cohen and by discussing sexual-affair hush money payments in the Oval Office. (15) Trump was not impeached for any of those possible offenses.

In late 2019, the House of Representatives impeached President Trump on a party-line vote because a whistle-blower came forward with a claim: Trump’s months-long conspiracy to use his office and taxpayer resources for his personal political benefit to get Ukraine to announce that it sought to investigate Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden. Trump compounded his troubles by refusing to release any relevant documents—except a summary of two calls between Trump and the Ukrainian president—or to allow any administration personnel to testify to the House Intelligence Committee about the matter. Several people involved in or knowledgeable of the conspiracy came forward and testified anyway, but principals including the president’s personal lawyer Rudy Giuliani, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, Acting Director of the Office of Management and Budget Mick Mulvaney, former National Security Advisor John Bolton, Vice President Michael Pence, Attorney General William Barr, and several other staff followed Trump’s direction and refused to come forward during the House investigation.

Ultimately, the House passed two articles of impeachment:

- Abuse of power by soliciting foreign interference in the 2020 election and compromising the national security of the United States, and

- Obstruction of Congress by the categorical and indiscriminate defiance of lawful Congressional subpoenas for information and testimony in an impeachment investigation.

Donald Trump’s Senate trial was a true low point in American political history. Republican senators blocked all attempts to request relevant documents and interview eyewitnesses to Trump’s alleged abuse of power. It was the first impeachment trial that heard from no witnesses and introduced no documents into the record. As far as the Republican senators were concerned, “facts and evidence—reality—were viewed as grave threats, which is why they had to be buried.” (16) Many aspects of the trial lent a kangaroo court character to the proceedings. Trump’s defense team didn’t attempt to present counter evidence—instead, they sought to rationalize the president’s actions—and Republican senators acknowledged that the president did what was alleged in the articles of impeachment. (17) One Republican senator attempted to get Chief Justice John Roberts to reveal the name of the whistleblower, but Roberts refused. While the trial was going on, new information came out in the media from one participant in the scheme—Lev Parnas—and one opponent of it—National Security Advisor John Bolton—who tried to shut it down because he knew it was illegal, but such evidence was not allowed to be heard in the trial. The Government Accountability Office confirmed during the trial that the president’s actions violated the Impoundment Control Act. (18) During the trial, Bolton’s upcoming book manuscript alleged that Pat Cipollone, the White House Counsel and part of Trump’s legal team, participated in the criminal conspiracy. (19) In the end, all Republicans except for Senator Mitt Romney (R-UT) voted “not guilty” on both articles of impeachment, and all Democrats voted “guilty” on both articles of impeachment—a result that fell far short of the two-thirds vote needed to remove Trump from office. Senator Romney voted “yes” on the abuse of power charge and “no” on the obstruction of Congress charge.

Two legacies of Trump’s first impeachment are likely to have long-term consequences. The first centers on the Trump administration getting away with blanket obstruction of a congressional inquiry. Republican senators seemed not to care about Congress’ institutional need to have Trump or any future president honor its subpoenas for documents and testimony. An executive whose actions cannot be investigated by Congress and who has a compliant Justice Department is more like an all-powerful monarch than an American president. That’s a frightening precedent for the Senate to set. The second concerns an especially pernicious legal argument put forward by Trump’s defense. Alan Dershowitz, one of Trump’s lawyers, said on the floor of the Senate that “Every public official that I know believes that his election is in the public interest. If a president does something which he believes will help him get elected in the public interest, that cannot be the kind of quid pro quo that results in impeachment.” This was an astounding argument that lacked any support in the scholarly or judicial record. (20) According to this line of thinking, a president could exercise his legal authority to declassify national security secrets for another country in exchange for that country’s help with his re-election. It is a way of thinking that subsumes the national interest of the United States underneath the personal political interest of the president.

Donald Trump’s Second Impeachment

At the close of President Trump’s first impeachment trial, Representative Adam Schiff made the following prophetic warning to the Senate: “He has not changed. He will not change. A man without character or ethical compass will never find his way. He has done it before and he will do it again. What are the odds if he is left in office that he will continue to try to cheat? I will tell you: 100%. He will continue to try to cheat in the election until he succeeds. Then what shall you say?” (21) Less than one year later, the U.S. House of Representatives was forced to impeach Trump for “incitement of insurrection,” which “followed his prior efforts to subvert and obstruct the certification of the results of the 2020 Presidential election.” (22)

The precipitating event for this second impeachment of Trump was the January 6, 2021 insurrection in which Trump supporters and allied domestic terrorists invaded the U.S. Capitol while Congress and the Vice President were gathered to carry out their Constitutional duty to certify the official Electoral College vote for Joe Biden and Kamala Harris—the Democratic ticket that won the popular vote by 7 million votes and the Electoral College vote by 306 to 232. The insurrectionists overwhelmed the outnumbered police forces that were protecting the Capitol and beat one of those police officers to death and injured at least 70 others. (23) They also appeared to be intent on capturing and possibly assassinating members of Congress and the Vice President. The rioters damaged parts of the building, defecated in its public spaces, and stole laptops and other material from Congressional offices. The January 6 insurrection marked the first violent presidential transition of power since the American Civil War that resulted from the secession of Southern states following the election of Abraham Lincoln.

Normally, politicians are not held accountable for the rash acts of their supporters. Trump, however, was not a normal politician and bore direct responsibility for this outrage. Consider the following sequence:

- Trump endorsed violence throughout his political life and often excused or ignored violence committed by his supporters. (24) He stirred up people in Michigan to “liberate” their state from duly elected officials, and then watched passively as armed citizens disrupted the state legislature. Nor did he issue a condemnation when a group of Michiganders were caught plotting to kidnap the state’s governor. In fact, he tweeted that the governor had done a “terrible job” and that she insufficiently thanked him for his non-existent role in catching the domestic terrorists. (25) When he discovered that some of his followers harassed a Biden campaign bus while it was traveling on an interstate highway in Texas, Trump tweeted “I love Texas!” (26) During a debate, when pressed about his support from domestic terrorist groups like the Proud Boys, Trump told groups like them to “stand back and stand by.” Members of those groups later participated in the January 6 insurrection.

- Trump was the first American president to declare before an election (twice, in fact, for 2016 and 2020) that he would not accept the results unless he won. If he didn’t win, that would be evidence in his mind—and in the minds of many of his supporters—that the process was rigged. (27)

- Months before the 2020 election, Trump claimed without evidence that it was going to be fraudulent and that mail-in ballots in particular were problematic. In fact, the 2020 election was the cleanest and most secure in modern American history. This fact was upheld by cyber-security analysts as well as (predominantly Republican) state and local officials and (predominantly Republican appointed) state and federal judges. (28)

- After the election, Trump and his associates pressured state and local officials in Arizona, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Georgia to find ways to either decertify the election results or change those results. In the case of Georgia, Trump told the Georgia Secretary of State, “Look, all I want to do is this: I just want to find 11,780 votes.” Trump had lost the popular vote in that state by 11,779 votes, so if the Secretary of State could actually “find” 11,779 + 1 extra Trump votes in that state, all of Georgia’s electors would have gone to Trump. (29)

- Long after the election had been called for Biden and Harris by all major news outlets including Fox News, Trump and his associates promulgated The Big Lie that he had won a “landslide” victory that the Democrats “stole” from him. He repeated The Big Lie and told his followers to come to Washington on January 6 to “fight like hell” and “fight to the death” or “you’re not going to have a country anymore.” He promised it would be “wild.” During the January 6 rally–when Trump already knew that attendees were armed and could not make it through the metal detectors surrounding his podium–he directed the crowd toward the Capitol building, saying they needed to “fight much harder,” “stop the steal,” and “take back our country.” (30) He also said that he would join the marchers, attempted to do so, but was not allowed to by his Secret Service detail.

- After the melee began on the Capitol steps, after the battering of the Capitol police, after the forced suspension of Congressional work, and after knowing that the chants of “hang Mike Pence” by the insurrectionists forced the Vice President’s security detail to rush him from the building, President Trump did not tweet to his followers to stop the violence. Instead, he tweeted “Mike Pence didn’t have the courage to do what should have been done to protect our Country and our Constitution, giving States a chance to certify a corrected set of facts, not the fraudulent or inaccurate ones which they were asked to previously certify. USA demands the truth!” Nor did he proactively call out the D.C. National Guard, which reports to the president. (31)

During the Senate trial, Trump’s lawyers largely did not dispute the facts of the case but made two substantial arguments and several minor ones. We’ll focus on the substantial ones. (32) Their first argument was that it was unconstitutional for the Senate to try Trump now that he was out of office, since the point of impeachment and trial is to remove the offender from office. In fact, the Constitution provides for an additional penalty upon conviction after an impeachment: “disqualification to hold and enjoy any Office of honor, Trust or Profit under the United States.” The argument that an impeachment trial cannot proceed once the alleged offender has left office would, if accepted, give presidents a free pass to violate the public trust in their final months in office. In fact, constitutional scholars overwhelmingly rejected Trump’s lawyers’ argument and argued that the Founders wanted the Senate to hold a trial in exactly these circumstances. (33)

The second argument put forward by Trump’s lawyers was that the president’s words and actions were protected by the First Amendment’s freedom of speech. They relied on Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969), in which the Supreme Court said Clarence Brandenburg could not be prosecuted for incitement to riot for his inflammatory speech given at a Ku Klux Klan rally. Again, constitutional scholars roundly rejected this defense for a sitting president stoking up his followers with lies, telling them they must act outside the law, and aiming them at the Congress and his own vice president. On the face of it, Trump’s lawyers made an important point: a president can tell Blacks to “go back to Africa” (akin to one of Brandenburg’s statements), or burn a flag at a rally, or deny the Holocaust while marching past a synagogue. Despicable as they are, all of these are technically protected forms of political speech, but that does not prevent Congress from impeaching and removing from office such a president for gross dereliction of duty, abuse of his office, and failure to preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution. The First Amendment, in other words, might protect Trump in any criminal or civil cases he faced as a result of his actions, but they do not restrain Congress when it comes to impeachment. (34) Remember, an impeachment article need not strictly be a violation of federal law.

Despite Trump’s weak defense in the Senate trial, he was quickly acquitted. It was the most bipartisan vote in presidential impeachment history, with seven Republican senators voting to convict. Still, the 57-43 majority vote was insufficient to meet the 2/3 threshold for conviction. In a head-scratching coda to the trial, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY), who voted to acquit the president, also made this clear statement: “Fellow Americans beat and bloodied our own police. They stormed the Senate floor. They tried to hunt down the Speaker of the House. They built a gallows and chanted about murdering the Vice President. They did this because they had been fed wild falsehoods by the most powerful man on Earth — because he was angry he’d lost an election. Former President Trump’s actions preceding the riot were a disgraceful dereliction of duty.” (35)

In terms of its overall impact for an attenuated democracy like ours, Trump’s acquittal on his second impeachment confirmed the lessons of his first acquittal and served as yet another warning that politicians and institutions lose all credibility when they don’t stand up to tyranny. It’s interesting to step outside the realm of partisan politics and listen to the voices of principled conservatives on this one. Charles Sykes, a commentator with impeccable conservative credentials, argued that under Trump’s leadership the Republican party had shown a “willingness to accept—or at least ignore—lies, racism, and xenophobia. But now [following the impeachment vote] it is a party that is also willing to acquiesce to sedition, extremism, and anti-democratic authoritarianism.” (36) Focusing his attention on the institutional failure of the Senate, conservative writer Jim Swift said the majority of its Republicans let the country down through sheer “partisan cowardice”: “Donald Trump incited an insurrection; the case against him was not refuted; and history will look back upon his acquittal with confusion and shame.” (37)

References

- As recorded in James Madison’s notes on July 20, 1787. Yale Law School’s Avalon Project.

- Keith Whittington, “The Power to Impeach Executive Officers,” Lawfare. August 4, 2017.

- Elizabeth Nix, “Has a U.S. Supreme Court justice ever been impeached?” History.com. December 2, 2016.

- Laurence Tribe and Joshua Matz, To End a Presidency. The Power of Impeachment. New York: Basic Books, 2018. Page 2. The Benjamin Franklin quote comes from page 1.

- Cass R. Sunstein, Impeachment. A Citizen’s Guide. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2017. Page 39.

- Note that the 25th Amendment later set up a formal process outside of impeachment to remove a president who is incapacitated.

- Tribe and Matz, To End a Presidency. Page 59.

- Alan Hirsch, Impeaching the President: Past, Present, and Future. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 2018. Page 23.

- Jon Meacham, “Andrew Johnson,” in Jeffrey Engel, Jon Meacham, Timothy Naftali, and Peter Baker, Impeachment. An American History. New York: Modern Library, 2018. Page 49.

- Jerry Zeifman, Without Honor: Crimes of Camelot and the Impeachment of Richard Nixon. New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press, 1996. Fred Emery, Watergate: The Corruption of American Politics and the Fall of Richard Nixon. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995.

- Timothy Naftali, “Richard Nixon,” in Jeffrey Engel, Jon Meacham, Timothy Naftali, and Peter Baker, Impeachment. An American History. New York: Modern Library, 2018. Pages 144-145.

- Eric Lichtblau and Allan C. Miller, “House Democrats Push for an Investigation of Starr’s Office,” Los Angeles Times. February 11, 1999.

- Washington Post, The Starr Report: The Findings of Independent Counsel Kenneth W. Starr on President Clinton and the Monica Lewinsky Affair. Public Affairs Reports, 1998.

- David Cay Johnston, The Making of Donald Trump. Brooklyn, NY: Melville House, 2017. Michael Kranish and Marc Fisher, Trump Revealed. The Definitive Biography of the 45thPresident. New York: Scribner, 2017. Steve Reilly, “Hundreds Allege Donald Trump Doesn’t Pay His Bills,” USA Today. June 9, 2016.

- Ron Fein, John Bonifaz, and Ben Clementz, The Legal Case for a Congressional Investigation on Whether to Impeach President Donald J. Trump. Free Speech for People. December 6, 2017. Trump’s 10 Impeachable Offenses. Need to Impeach.

- Peter Wehner, “The Downfall of the Republican Party,” The Atlantic. February 2, 2019.

- Christal Hayes, “’He Shouldn’t Have Done It.’ GOP Senator Who Scolded Trump on Ukraine Explains Why He Backs Acquittal.” USA Today. February 1, 2020. Chris Cillizza, “Marco Rubio’s Mind-Blowing Explanation of His Impeachment Vote,” CNN. February 1, 2020.

- Dareh Gregorian, ”Trump Administration Violated the Law by Withholding Ukraine Aid, Government Accountability Office Says,” CBS News. January 16, 2020.

- Travis Gettys, “’Holy Crap!’ Bolton ‘Directly Implicated’ Pat Cipollone as a ‘Fact Witness’ in Trump Impeachment Trial,” Rawstory. January 31, 2020.

- Dershowitz quoted by Allan Lichtman in “What Will the History Books Say About This Impeachment?” Politico. February 5, 2020.

- Adam Schiff quoted in Tom McCarthy, “Trump Impeachment Trial: Democrats Warn that Trump ‘Will Do It Again’ if Acquitted,” The Guardian. February 3, 2020.

- Res. 24 of the 117th Congress. January 13, 2021.

- Jacob Fenston, “’January 6 Forever Changed This Department,’ Capitol Police Chief Says, One Month After Attack,” DCist.com. February 6, 2021.

- Fabiola Cineas, “Donald Trump is the Accelerant,” Vox. January 29, 2021.

- Craig Mauger, “President Trump Tweets on Kidnap Plot, Criticizes Gov. Whitmer,” The Detroit News. October 8, 2020.

- Kate McGee and Jeremy Schwartz, “President Trump Tweets I LOVE TEXAS! Along With Video of Trucks Surrounding Biden Bus,” CBSAustin. November 1, 2020.

- Jeremy Diamond, “Donald Trump: ‘I Will Totally Accept’ Election Results ‘If I Win,’” CNN. October 20, 2016. Sanya Mansoor, “’I Have to See.’ President Trump Refuses to Say If He Will Accept the 2020 Election Results,” Time. July 19, 2020.

- No author, “It’s Official: The Election Was Secure,” The Brennan Center for Justice. December 11, 2020.

- Jamie Raskin, et al., Trial Memorandum of the U.S. House of Representatives in the Impeachment Trial of Donald J. Trump. February 2, 2021.

- Josh Wingrove and Margaret Newkirk, “Trump Urged Georgia Officials to Find Votes, Flip State to Him,” Bloomberg. January 3, 2021. Anita Kumar and Gabby Orr, “Inside Trump’s Pressure Campaign to Overturn the Election,” Politico. December 21, 2020.

- Robert Farley, “Timeline of National Guard Deployment to Capitol,” FactCheck.org. January 13, 2021.

- Dana Farrington, “Trump’s Impeachment Defense Brief,” NPR. February 8, 2021.

- Multi-authored public statement, Constitutional Law Scholars on Impeaching Former Officers. January 21, 2021. Jed Handelsman Shugerman, “Impeach an Ex-President? The Founders Were Clear: That’s How They Wanted It,” Politico. February 11, 2021. Stephen Vladeck, “Why Trump Can Be Convicted Even as an Ex-President,” New York Times. January 14, 2021. Keith Whittington, “Can a Former President Be Impeached and Convicted?” Lawfare. January 15, 2021.

- Peter Keisler and Richard D. Bernstein, “Freedom of Speech Doesn’t Mean What Trump’s Lawyers Want it to Mean,” The Atlantic. February 8, 2021. Ian Millhiser, “Trump’s False Claim That Impeachment Violates the First Amendment, Explained,” Vox. February 12, 2021.

- No author, “Read McConnell’s Remarks on the Senate Floor Following Trump’s Acquittal,” CNN. February 13, 2021.

- Charlie Sykes, “Trump’s Party, But Worse: Acquitted But Not Exonerated,” The Bulwark. February 15, 2021.

- Jim Swift, “Trump’s Acquittal is an Ignominious Failure,” The Bulwark. February 13, 2021.

Media Attributions

- Impeachment Johnson © Library of Congress is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Impeachment Nixon © Hartmann is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Impeachment Clinton © White House Photograph Office is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Impeachment Trump © Shealah Craighead is licensed under a Public Domain license