7.3: Chapter 43- Policy Preferences of American Political Parties

- Page ID

- 73484

How Political Scientists Analyze Parties

Political parties are complicated beasts, and not at all easy to capture in American Government textbooks. Political scientists tend to break the analytical problem down into three parts. (3)

The party in the electorate refers to the voters who support each party. Even this is difficult, because people may support the Democratic or Republican parties—or one of the third parties—without formally registering as a party affiliate. Indeed, one can say that the largest “party” in the United States are those who either intentionally refuse to commit to one of the parties or who have turned away from partisan politics altogether. However, even these Independents tend to favor the political positions of one party over another. Party affiliation tends to wander over time. Generally speaking, Republicans and Democrats each tend to constitute somewhere between 25-33 percent of the population, with Independents making up the rest. (4) Political scientists and survey researchers use the term party identification to refer to a voter’s self-identification with one party or another, whether or not they are formally party members. Through survey research, political scientists can make statements about the extent to which people who identify with one party support policy A versus policy B.

The party organization deals with what we talked about in a previous chapter—i.e., people who hold offices or volunteer positions in a political party at the local, state, or national level. They tend to be quite dedicated, devoting considerable time and effort promoting the party, its policies, and its candidates. This is a finite number of people, and political scientists can study them through both qualitative and quantitative methods. For instance, scholars can study the extent to which the political views of national party convention delegates are similar to or differ from those of rank and file party members. (5)

The party in government refers to elected and appointed public officials who identify with one party or another. As with party organization, this is a relatively well-defined universe of people that can be subdivided into precise groups like members of the House of Representatives or U.S. Senators. The behavior of these groups can be analyzed using quantitative and qualitative measures. For instance, the overall partisanship of Representatives and Senators can be analyzed by looking at the percentage of congressional votes that pit a majority of Democrats on one side voting against a majority of Republicans on the other side. Individual representatives or senators can be given partisanship scores for how closely they adhere to the party line, and those results can be compared to the voters’ views. (6)

These modes of analysis tend to accentuate the differences between Democrats and Republicans, regardless of whether we’re talking about ordinary voters, people who hold positions in party organizations, or public officeholders. They can tell us, for example, that party identification is remarkably stable over long periods of time. (7) They can also tell us that while a majority of all Americans think there is too much economic inequality, people who identify as Democrats are considerably more likely to think so than are people who identify as Republicans. (8) These analyses are also mentioned prominently in news media accounts of American politics.

A Critical Examination of the Democratic and Republican Parties

If we want to critically examine America’s dominant political parties, we should start with the economic context in which they operate. The Democratic and Republican parties contest for political power within a society that has long embraced a variant of capitalism marked by monopolies and oligopolies, by the privileged place of business in the political landscape, by stark economic inequality, and by a devaluation of the public versus the private sphere. (9) In turn, the dominant political parties often act to reify this particular capitalist system. A visitor from outer space who studied American politics would quickly note how the Democratic and Republican parties both seem to behave as though they existed primarily to execute the policies desired by financial institutions, large corporations, real estate developers, and insurance companies. In the famous words of scholar Noam Chomsky, “The United States has essentially a one-party system and the ruling party is the business party.” (10) As we’ll see in the chapter on campaign finance, almost all candidates from both political parties depend on money from businesses and their top management personnel to fund their campaigns.

Setting this context is necessary to understand the Democratic and Republican parties, but it’s not entirely sufficient. We need to keep our eye on another set of variables. As dominant as are the artificial people called corporations in the political party landscape, we have to be mindful that parties are coalitions of actual people as well—and actual people still retain a privilege not yet afforded by the Supreme Court to corporations. People vote, and through their votes they nominate candidates and elect politicians. Furthermore, ordinary Americans’ interests do not fully align with the interests of capitalists. To be sure, actual people need the jobs that corporate America provides, which means that workers and their employers are co-invested in a prosperous economy. Beyond that, however, the interests of living, breathing people and the interests of artificial people—i.e., corporations—diverge either somewhat or completely. This fact creates tensions and divisions within America’s dominant political parties, because elites and ordinary people contest each other over the policy programs on which political parties campaign. For example, Wall Street firms that give so much money to the Republican party—they give to both parties—don’t share the political goals of evangelical Christians, who are currently a significant part of the Republican coalition.

The interest alignment and misalignment between the corporate funders of America’s political parties and the coalitions of people who are party members or party identifiers is fertile ground for examining the three dimensions of power. Obviously, the first dimension of power manifests itself as party adherents vote in primaries and caucuses to nominate candidates to run in general elections. The second dimension of power can be seen clearly when party establishments—party leaders, who tend to be elites most closely tied to corporate sponsors—attempt to put their finger on the scales during the nominating process. This can happen at any level, but it gets the most attention at the presidential level. In 2016, the Republican party establishment was powerless to stop Donald Trump’s insurgent campaign to become the Republican presidential nominee. On the Democratic side, however, Bernie Sanders’ progressive movement was successfully stymied by party leaders. A secret agreement between the Democratic National Committee and Hillary Clinton’s campaign essentially gave Clinton’s camp “control (of) the party’s finances, strategy, and all the money raised” well before the nomination season had even started. In addition, the Democratic National Committee chairwoman gave Clinton an early look at what was going to be asked at a debate between the two candidates. (11) While it’s likely that Clinton would have gotten the nomination anyway for a number of reasons, the whole escapade nicely illustrates the second dimension of power in action. In the 2018 presidential nomination season, corporate leaders and corporate media put on a full-court press against the two progressive candidates, threatening to withhold support, red-baiting Sanders in particular, and hoodwinking ordinary people into thinking that the corporate-backed candidates actually had their interests in mind. (12) It was a classic illustration of the third dimension of power.

The Republican Party, which is the principal vehicle for conservatism in America, is caught in what political scientists Jacob S. Hacker and Paul Pierson refer to as the conservative dilemma, which arises “when an economic system that concentrates wealth in the hands of the few coexists with a political system that gives the ballot to the many.” Here’s the dilemma: how does a party that serves the interests of concentrated wealth win enough votes from ordinary people? The conservative dilemma has plagued conservative parties in many countries, but appears to be particularly acute in the American context where the Republican Party, according to Hacker and Pierson, embraces policies that serve corporations and the economic elites while campaigning to voters using appeals to White grievance, ginned up moral outrage (for example, at “rigged elections,” or “critical race theory”), fears of creeping socialism, issues like guns and abortion, and outrage at the very elites Republicans serve with their tax breaks and deregulation agenda. (13).

Similarities and Differences Between the Democratic and Republican Parties

The analysis above suggests that there is a tug-of-war between ordinary Americans and elites over who is going to be able to capture America’s dominant political parties and use them to serve their interests. Sheldon Wolin, the political scientist whose quotes start the chapter, argues that both parties are fully captured by America’s corporate elite. This view is shared by historian Howard Zinn as well as writer and theologian Chris Hedges, who argues that corporate dominance of the parties has led many ordinary people to buy into “the con that deindustrialization, deregulation, austerity, bailing out the banks, nearly two decades of constant war, the exporting of jobs overseas, tax cuts for the rich and the impoverishment of the working class were forms of progress.” (14) Still, the corporate agenda inherent in both major American parties has to live alongside the aspirations of the millions of people who identify as Democrats or Republicans. How does this manifest itself?

The Democratic and Republican parties show remarkable similarities on many policies including mass incarceration, governmental and private sector surveillance of the population, and a campaign finance system that puts corporations and the wealthy in the driver’s seat. (15) However, we’ll focus here on two related policies upon which the two major parties agree. The fact that both parties have enthusiastically pursued these policies shows the political power of corporations and the elites who staff their upper echelons. It is these very policies that lead to much disillusionment among the rank and file members of both parties. Robert Reich, public policy professor and a former Secretary of Labor, confirmed this fact through his many interviews with people around the country:

“I heard the term ‘rigged system’ so often I began asking people what they meant by it. They spoke about the bailout of Wall Street, political payoffs, insider deals, CEO pay, and ‘crony capitalism.’ These came from self-identified Republicans, Democrats, and Independents; white, black, and Latino; union households and non-union. Their only common characteristic was they were middle class and below.” (16)

Judged by their behavior in office, the Democratic and Republican parties agree on these major points:

American Imperialism—Following World War II, the United States was a superpower, a nation-state able to project military, economic, and cultural power all across the globe. Its only rival from 1945 to 1991 was the Soviet Union, and the United States under both parties pursued an aggressive policy of trying to contain and push back against perceived communist advances around the world. Even beyond the U.S.-Soviet rivalry, America took on the role of the world’s policeman. Some American actions seemed justified like the defense of South Korea when North Korea invaded in 1950. Most, however, were of dubious strategic and moral value. These include intervening against the will of people who wanted leftist governments in places like Iran, Guatemala, and Chile; sponsoring a failed invasion of Cuba to unseat the Castro regime; and invading various places from Grenada to Panama. The most destructive of these interventions was America’s futile involvement in the Vietnam War, which did nothing but prolong the unification of the country, kill 58,000 American soldiers, wound another 300,000 American soldiers, and kill an estimated 3.3 million Vietnamese soldiers and civilians. (17)

After the Soviet Union’s demise, there was no peace dividend for the American people, as new threats—mostly of our own creation—confronted superpower America. The U.S. funded Saddam Hussein’s regime in Iraq, and then ended up going to war with Iraq when Hussein misread our commitment to Kuwait. The U.S. also funded fundamentalist Islamic rebels in Afghanistan. The presence of American troops in the Middle East—especially in Saudi Arabia—and the U.S. defending Israel in suppressing Palestinians blew back on the United States. The al Qaeda network retaliated by trying to bring down one of the World Trade Center towers in 1993 with a truck bomb, attacking the USS Cole in 2000, and then carrying out the catastrophic terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 that brought down both World Trade Center towers with commercial airliners, damaged the Pentagon with another jet, and resulted in the crash of one more commercial airliner in Pennsylvania. The U.S. then did exactly what the terrorists hoped for—it got bogged down in invading Afghanistan and Iraq. Meanwhile, American presidents of both parties have become enamored of using military air strikes and drone strikes in places like Libya, Yemen, Pakistan, and Syria.

The tension between the corporate sponsors of the parties and the American people is palpable. The American penchant for drone strikes and invasions to meet its international obligations as a superpower have been very good for the military-industrial complex about which President Eisenhower warned. It has also undoubtedly opened markets for American and other international corporations. However, America’s militarism has led the people of the world to conclude that the United States is the greatest danger to the world, a result that can’t possibly contribute to overall American security. (18) And yet, after expending all this blood and money, Americans feel less safe with every new military adventure. (19) They seem to want some treasure spent instead to fix America’s infrastructure, to provide health care, to prevent undocumented immigrants from entering the country, to deal with environmental challenges, and to support public schools. (20)

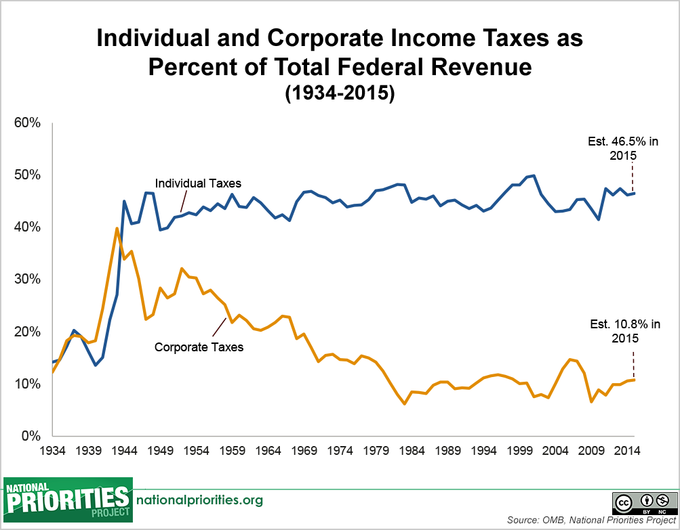

Laissez-faire Economic Policy—While the Republican party has been a little more enthusiastic in this regard, for many decades both political parties have pursued clear laissez-faire economic policies. Laissez-faire is French for “allow to do,” and refers to a hands-off approach to economic policy that leaves corporations to do as they please with limited tax and regulatory burdens. This approach is also called neo-liberalism, which is a brand of conservatism that is particularly strong in the United States and reminds us that the original liberals in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries opposed monarchy and wanted limited government. I know—the term neo-liberalism means conservative? It’s confusing. Remember that the wealthy and large corporations are the major funders of American political parties and candidates. They also control the positions government leaders go to when they walk through the revolving door. These two facts—combined with the triumph of laissez-faire/neo-liberal philosophy in America—mean that politicians and leaders of both political parties are predisposed to pursue policies that further the power of corporations and the wealthy.

What policies are we talking about? Congress and presidents of both parties have done the following: Lowered corporate taxes. Weakened insider trading rules. Deregulated banks, savings and loans, and other financial institutions that have used their freedoms in very predatory and reckless ways. Incentivized corporations to pay executives with stock options and encouraged corporations to buy back their own stock rather than pay workers or invest in new capacities. Put a lid on the federal minimum wage. Allowed anti-trust laws to languish on the books, encouraging monopolies and oligopolies in industries as varied as social media, telecommunications, and pharmaceuticals. (21) Passed trade agreements that put American workers in direct competition with low-paid workers in poorly regulated countries. Encouraged American companies to close factories here and move them abroad. Shaped bankruptcy law to allow corporations to wiggle out of obligations—like worker pay and benefits agreements when things turn south, but then trap average Americans with debts—like college loans—that cannot be escaped. Allowed the predatory payday loan industry to proliferate. Bailed out Wall Street banks for their reckless behavior that led to the 2008 Great Recession while leaving average Americans holding the bag. (22)

Laissez-faire policies have fueled America’s growing economic inequality. In other words, they’ve been great for corporations and those who were already in the top 10 percent income bracket. They have been a disaster for the bottom 60 percent of Americans. Further, they have contributed to the conclusion of many Americans that the establishment wings of both political parties have built this “rigged system” that they want torn down and replaced with a system that works for ordinary people. Neither party wants to do anything meaningful about challenging wealth and income concentration and getting us past laissez-faire policies.

The Democratic and Republican parties show clear differences on the following policies. Note, however, that what follows are necessarily generalizations. Individual Republicans can and do buck the tendencies described below, and so do individual Democrats. Note also that this is not an exhaustive list of partisan differences.

Taxes—Democrats and Republicans generally subscribe to two different economic policies. Conservatives tend to be advocates of what is known as supply-side economics. Supply-siders argue that economic growth is best promoted by lowering tax rates on wealthier individuals and corporations. The primary assumption of supply-side economics is that the recipients of these tax breaks will invest their extra money to expand existing businesses and create new ones. This, in turn, will put more people to work, and the workers will spend their paychecks to purchase goods and services. Democrats tend to come at the issue of economic growth from the bottom up, although demand-side economics is not really a term people use like they do supply-side economics. Rather than providing tax incentives for wealthy individuals and corporations, Democrats tend to support tax cuts for middle-class people, policies like increasing the minimum wage, and social programs for poor people. Their assumption is that these people are more likely to go out and spend that money, stimulating demand, and prompting wealthy individuals and companies to invest in businesses to meet that demand.

Civil Rights—It’s true that for much of its history, the Democratic party was the place to be for Southern Whites fighting against school integration, voting rights, equal employment opportunities, an end to housing discrimination, and so forth. However, the success of the Republican party’s Southern Strategy combined with Roosevelt’s New Deal in the 1930s and the Johnson administration’s advocacy of civil rights in the 1960s essentially flipped the narrative. It’s clear that since the 1970’s, the Democratic party has been more welcoming than the Republican party of equal rights regardless of race, sex, and sexual orientation. To be sure, many of the Democratic party’s leaders like the Clintons and the Obamas followed the lead of the Democratic rank and file rather than actually taking morally courageous stands on civil rights. Still, it has been the Republican party’s leaders as well as its ordinary members who have generally found the civil rights revolution unsettling. In the period from the 1970’s forward, the Republican party opposed the Equal Rights Amendment, opposed gay rights and gay marriage, turned a deaf ear to the Black community’s concerns about disproportionate police violence, and tried wherever it could to ensure that people used the bathroom that conformed to their birth certificate rather than their gender expression. The Republican party has been trying to use religious freedom as a tool to blunt the impact of civil rights—allowing, for example, religious people to discriminate against the LGBTQ community on religious grounds.

Female Bodily Autonomy—Although there are exceptions, Republicans tend to want to control women’s bodies whereas Democrats tend to defer to women to make intimate procreative decisions. (23) This division reflects the conservative impulse to maintain established social hierarchies and the progressive impulse to tear them down in favor of equality and individual autonomy. It’s a basic philosophical difference between ordinary Americans when it comes to this and other issues. Should the law be used to prevent women from terminating pregnancies caused by rape and incest, pregnancies that jeopardize their health, and pregnancies that would trap them in abusive relationships? Republicans are more likely to say yes. Should the government help support women’s reproductive services that include abortion? Should health insurance policies cover contraception and abortion? Democrats are more likely to say yes. (24) While Republicans would generally ban all abortions at any stage, Democrats would generally ban abortion late in a pregnancy and allow exceptions for the health and life of the pregnant woman.

Gun Control—The Democratic and Republican parties differ on measures to reduce America’s epidemic of gun violence. Americans die by gun violence at four times the rate of people living in war-torn Yemen and Syria. Gun deaths occur in the United States at a rate 74 times that of the United Kingdom and 111 times that of Japan. (25) Democrats tend to favor measures such as universal background checks, waiting periods, bans on assault style weapons, limitations on clip sizes, and gun registries, whereas Republicans tend to oppose them. The Supreme Court has affirmed that the Second Amendment to the Constitution confers an individual right to bear arms, but the Court has also said that regulation of firearms is permitted. In his majority opinion in District of Columbia v. Heller (2008), conservative Justice Antonin Scalia wrote “nothing in our opinion should be taken to cast doubt on longstanding prohibitions on the possession of firearms by felons and the mentally ill, or laws forbidding the carrying of firearms in sensitive places such as schools and government buildings, or laws imposing conditions and qualifications on the commercial sale of arms.”

The Environment—While Republicans and Democrats tend to agree on a laissez-faire approach to the economy, including fairly relaxed corporate regulations, they do differ somewhat on the environment. This difference has been most notable from the late 1970s onward. The Democratic party has been more supportive of regulations designed to promote clean air and water, stricter protective designations for public lands, increased fuel efficiency standards for vehicles, renewable energy incentives, and measures to fight climate change. The Republican party takes a hands-off approach to environmental regulation and works to blunt or remove environmental regulations that are already in place.

Healthcare—There have long been differences between Democrats and Republicans on healthcare. Republicans have repeatedly teamed up with the healthcare industry to fight Democratic efforts to develop a national healthcare system in which all people would receive equal coverage and treatment. In 1945, Democratic President Truman put forward a national healthcare plan and was defeated by opposition from Republicans, the American Medical Association, and insufficient interest on the part of the voting public. (26) When Democratic President Lyndon Johnson created the Medicare and Medicaid programs, Republicans opposed them by saying they meant the end of freedom in America. (27) Similarly, Republicans opposed Democratic President Barack Obama’s Affordable Care Act, even though the program was very pro-corporation and originated in a conservative think tank. (28) The telling historical fact is that even when Republicans held the White House and had both the House and Senate majorities, they did not formulate—let alone pass—a law designed to promote widespread healthcare coverage in the United States. The United States is the only advanced country without a national healthcare system; instead, we’ve opted for a patchwork one that leaves millions of people uncovered, results in frequent medical bankruptcy, and costs twice as much per capita as the systems in other countries. (29)

The Asymmetrical Nature of American Party Politics

Before we leave the topic of the two dominant political parties in America, we want to make sure that we understand what political scientists refer to as the asymmetric nature of the Democratic and Republican parties. Many political scientists have noted this distinction, but Matt Grossman and David Hopkins put it most authoritatively in their book Asymmetric Politics. In the modern era, the Democratic party is best characterized as a relatively non-ideological coalition of distinct groups like women, Blacks, the LGBTQ community, Hispanics, labor unions, environmentalists, and so forth. It’s a “big tent” party whose constituent groups sympathize and often support each other, but who have not created a powerful ideology to animate them all. Absent an overarching liberal or progressive ideology, the “Democrats continue to address the concrete agendas of discrete social groups, preferring a governing style of technocratic incrementalism over one guided by a comprehensive value system.” (30) This may explain the difficulty that relatively ideological Bernie Sanders had in trying to become the Democratic party presidential nominee in 2016 and 2020.

The Republican party, on the other hand, is one notably characterized by “movement conservatism,” an ideology of individual liberty that unites and animates its members. Whenever its candidates lose, the Republican party tends to conclude that the reason for the loss was that its particular candidate in a given race was not ideologically pure enough. The Republican party unites business and religious interests under a conservative banner clearly intended to prevent any cracks in the economic or social hierarchies that have developed in America. The conservative movement has shown “spectacular success in gaining control of the Republican Party.” (31) When outsider Trump gained the White House and became the Republican party’s de facto leader, it’s interesting that the two main reactions of conservatives were either to leave the party to maintain ideological purity or try to co-opt the opportunity provided by the Trump presidency to promote conservative ideological values in public policy and federal court nominations.

References

- Sheldon S. Wolin, Democracy, Inc.: Managed Democracy and the Specter of Inverted Totalitarianism. New Edition. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017. Page 187.

- Sheldon S. Wolin, Democracy, Inc.: Managed Democracy and the Specter of Inverted Totalitarianism. New Edition. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017. Page 201.

- L. Sandy Maisel, American Political Parties and Elections. A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016. Pages 77-90.

- John Laloggia, “6 Facts About U.S. Political Independents,” Pew Research Center. May 15, 2019.

- Examples: Richard Herrera, “Are ‘Superdelegates’ Super?” Political Behavior. Vol, 16, No. 1. 1994. Jeanne Kirkpatrick, “Representation in the American National Conventions: The Case of 1972,” British Journal of Political Science, Vol. 5, No. 3. July 1975. Ronald Rapoport, Alan I. McGlennon, and John Abramowitz, The Life of the Parties: Activists in Presidential Politics. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky, 1986.

- For example, Logan Dancey and Geoffrey Sheagley, “Partisanship and Perceptions of Party Line Voting in Congress,” Political Research Quarterly, Vol. 71, No. 1. March 2018.

- Pew Research Center, “Party Identification Trends,” 1992-2017. March 20, 2018.

- Juliana Menasce Horowitz, Ruth Igielnik, and Rakesh Kochnar, “Most Americans Say There is Too Much Economic Inequality in the U.S., But Fewer Than Half Call It a Top Priority,” Pew Research Center. January 9, 2020.

- Matt Stoller, Goliath: The 100-Year War Between Monopoly Power and Democracy. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2019. William Hudson, American Democracy in Peril: Eight Challenges to America’s Future. 6thEdition. Washington, D.C.: CQ Press, 2010. Pages 213-249.

- “Interview With Noam Chomsky,” Der Spiegel. October 10, 2008.

- Greg Price, “Hillary Clinton Robbed Bernie Sanders of the Democratic Nomination, According to Donna Brazile,” Newsweek. November 2, 2017. Amber Jamieson, “DNC Head Leaked Debate Question to Clinton, Podesta Emails Suggest,” The Guardian. October 31, 2016.

- Brian Schwartz, “Wall Street Democratic Donors Warn the Party: We’ll Sit Out or Back Trump, If You Nominate Elizabeth Warren,” CNBC. September 26, 2019. Julie Hollar, “Here’s the Evidence Corporate Media Say is Missing of WAPO Bias Against Sanders,” Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting. August 15, 2019. Dave Lindorff, “The Red-Baiting of Bernie Sanders Has Begun and is Already Becoming Laughable. Counterpunch. February 13, 2020.

- Jacob S. Hacker and Paul Pierson, Let Them Eat Tweets: How the Right Rules in an Age of Extreme Inequality. New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 2020. Quote from page 17.

- Chris Hedges, “US Election 2020: A Circus Then, A Circus Now,” Geopolitics. January 22, 2020.

- Chris Hedges, “Class: The Little Word the Elites Want You to Forget,” Truthdig. March 2, 2020.

- Robert Reich, “Bernie Sanders is Not George McGovern,” Truthdig. February 28, 2020.

- Ronald H. Spector, “Vietnam War,” Encyclopedia Britannica. February 14, 2020.

- Eric Zuesse, “Polls: U.S. is the ‘Greatest Threat to Peace in the World Today.’” Gobal Research. August 9, 2017.

- ABC News/Ipsos Poll. January 12, 2020.

- Kim Parker, Rich Morin, and Menasce Horowitz, “Worries, Priorities, and Potential Problem Solvers,” Pew Research Center. March 21, 2019.

- A monopoly is when one company dominates an economic sector. An oligopoly is when a few companies do so. See Thomas Philippon, The Great Reversal: How America Gave Up on Free Markets. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2019. Philippon estimates that monopolies and oligopolies in America cost Americans an extra $300 per month and short workers about $1.25 trillion a year in wages.

- Joseph E. Stiglitz, Rewriting the Rules of the American Economy. An Agenda for Growth and Shared Prosperity. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2015. Robert B. Reich, Saving Capitalism: For the Many, Not the Few. New York: Vintage Books, 2016.

- I reject the pro-choice/pro-life dichotomy because it obscures more than it illuminates. A better road into this issue is the extent to which the government should be able to control the bodies of women.

- Katie Watson, Scarlet A: The Ethics, Law, & Politics of Ordinary Abortion. New York: Oxford University Press, 2019.

- Marc Silver, “A Doctor’s Insights into Gun Violence and Gun Laws Around the World,” NPR. August 6, 2019. Nurith Aizenman and Marc Silver, “How the U.S. Compares with Other Countries in Deaths from Gun Violence,” NPR. August 5, 2019.

- Howard Markel, “69 Years Ago a President Pitches His Idea for National Healthcare,” PBS Newshour. November 19, 2014.

- In 1961 Ronald Reagan said that if Medicare is not stopped, “one of these days you and I are going to spend our sunset years telling our children and our children’s children what it once was like in America when men were free.” Igor Volsky, “Flashback: Republicans Opposed Medicare in 1960s by Warning of Rationing, ‘Socialized Medicine,’” Thinkprogress. July 29, 2009.

- Avik Roy, “The Torturous History of Conservatives and the Individual Mandate,” Forbes. February 7, 2012.

- Peter G. Peterson Foundation, “How Does the U.S. Healthcare System Compare to Other Countries?” July 22, 2019.

- Matt Grossman and David A. Hopkins, Asymmetric Politics: Ideological Republicans and Group Interest Democrats. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016. Page 101.

- Matt Grossman and David A. Hopkins, Asymmetric Politics: Ideological Republicans and Group Interest Democrats. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016. Page 79.

Media Attributions

- DSC_0633.JPG © David Hubert is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- 911 © cattias.photos is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives) license

- Corporate Taxes © National Priorities Project is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license