7.4: Chapter 44- Why Do We Have a Two-Party System?

- Page ID

- 73485

A Two-Party System and Its Alternatives

Causes of America’s Two-Party System

The consensus among political scientists is that two structural features strongly favor a two-party system as opposed to a multi-party system. The first consists of a variety of laws that limit ballot access and otherwise penalize third parties. For instance, congressional rules all favor the Democrats and Republicans. If someone from a third party or a person with no party affiliation is elected to Congress, they must choose to be affiliated with one of the major parties to get assignments to standing committees. Presidential candidates from the major parties can receive public money to run their campaigns. But when a third-party candidate runs for president and wants public funding through the Federal Election Commission, they have to receive that funding after the election is over because the amount is tied to how well they did in the last election.

Third parties complain loudest about ballot-access restrictions, which are barriers to getting a candidate on the ballot so voters don’t have to write in their name. They argue that were today’s ballot-access restrictions in place in the 1850s, the Republican Party never would have risen to become a national party. As political analyst Richard Winger points out, the first ballot-access restrictions began in the late 1880s and became progressively stricter in the 1930s and the 1960s. (2) Natural experiments have shown that when ballot-access restrictions were lowered, the major parties faced significantly increased competition from third party and independent candidates. (3)

Ballot-access restrictions include filing fees, early deadlines to declare candidacy, and signature requirements. The latter is perhaps the most onerous burden on third parties. Many states require independent and third-party candidates to secure enough signatures on petitions in order to get on the ballot. Simply put, “The greater the share of the electorate required to sign nominating petitions, the fewer minor-party and independent candidates appear on the ballot.” (4) A third party that wants to run candidates for all the House seats across the country would have to collect millions of signatures. The Democrats and Republicans are relieved of this burden. Collecting these signatures is expensive and time-consuming. Together, filing fees and signature requirements stunt electoral competition, especially in races for the House of Representatives. (5)

The second structural element causing the United States to have a two-party system is our winner-take-all elections—which the British refer to as a first-past-the-post system—used in single-member districts. In such a system, a single person represents each electoral district for the House or Senate and gets that distinction by receiving the most votes of those cast, even if they did not receive the majority of the votes. So, if Juan receives 546 votes, Mary receives 545 votes, and Tarek receives 544 votes in a U. S. House of Representatives’ election, Juan wins even though he received only 33 percent of the vote. He received the most votes short of a majority, called the plurality of votes, and he will represent that district. Coming in second gets Mary nothing, and Tarek is similarly out of luck even though he received only 2 votes less than the winner. The tendency for winner-take-all, single-member district systems to promote two parties is sometimes referred to as Duverger’s Law, after the French political scientist Maurice Duverger.

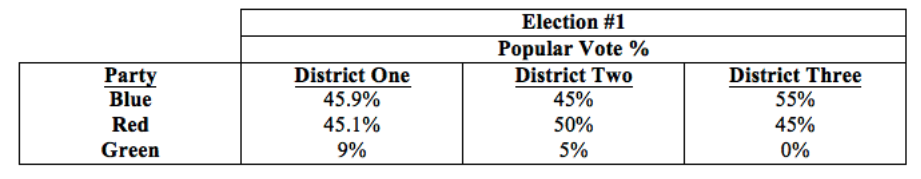

How does the winner-take-all system help create a two-party system? To answer that, we’re going to need a more realistic example. Let’s say we have a progressive party that pushes the interests of the common laborer but has also been somewhat environmentally friendly—the Blue Party, and we have a conservative party that pushes the interests of big business and entrepreneurs and is very unfriendly to the environment—the Red Party, and we have a new party that is very concerned about the environment—the Green Party. Let’s assume we have three election districts, and the Green party starts strongest in one region. Finally, let’s be realistic and say that the Green Party does not have the strength that third-place winner Sam did in our example above. We have an election, and these are the results:

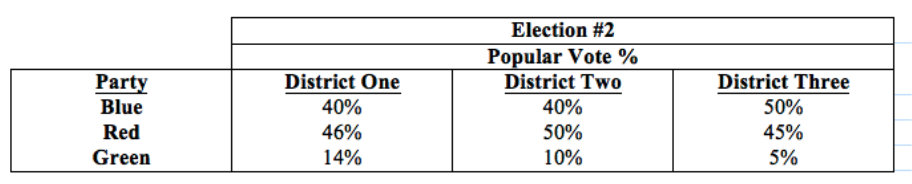

Indeed, the Greens did a bit better, but what did it get them? Still nothing. The first lesson from this is that it’s very difficult to keep a new party going year after year if all that effort is not producing actual legislative seats. In this case, the Green party saw tremendous gains for a third party. That’s often not the case, and so aside from keeping the party going, it becomes difficult to convince citizens to keep voting for a loser that has little chance of gaining seats in Congress. People want to vote for a party that stands at least some chance of winning seats. That’s the second lesson. The third lesson is equally important. Look what happened in that second election. Green pulled voters away from Blue, which is the second choice among eco-voters because it is at least somewhat environmentally friendly. By doing so, these voters hurt the Blue party and guaranteed that Red would pick up another seat even though Red’s support didn’t actually go up. Since the average Green voter despises the Red party program, their support for the Green party in the election booth has led to the perverse result of having helped Red carry out its anti-environment program. In District One during Election #2, the Green candidate was the so-called spoiler candidate, who pulled enough votes away from the Blue candidate to ensure that Red won the seat.

What is a Green voter to do? One choice is to keep voting Green with the hope that the Blue party will self-destruct so that the Greens will be the only real alternative to the Reds. Something like that hasn’t happened in the United States since the 1850s, so it’s not very likely. Still, some people make this choice on principle. Many others, however, tend to stay within the Blue party and work to make it more environmentally friendly, which deprives the Green party of activists and undercuts the distinctive Green party call among the broader electorate.

What If?

References

- Christopher H. Achen and Larry M. Bartels, Democracy For Realists: Why Elections Do Not Produce Responsive Government. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016. Page 19.

- See Richard Winger, editor of Ballot Access News, “The Importance of Ballot Access,” archived here. Richard Winger, “Institutional Obstacles to a Multiparty System,” in Paul S. Herrnson and John C. Green, editors, Multiparty Politics in America. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 1997.

- Marcus Drometer and Johannes Rincke, “The Impact of Ballot Access Restrictions on Electoral Competition: Evidence from a Natural Experiment,” Public Choice. September 25, 2008. Pages 461-474.

- Barry C. Burden, “Ballot Regulations and Multiparty Politics in the States,” PS: Political Science and Politics. October, 2007. Page 671.

- Stephen Ansolabehere and Alan Gerber, “The Effects of Filing Fees and Petition Requirements on U.S. House Elections,” Legislative Studies Quarterly. 21(2). May 2, 1996.

- See: Fairvote. Ranked Choice Voting Resource Center.

Media Attributions

- Election #1 © David Hubert is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Election #2 © David Hubert is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license