8.1: Chapter 49- Expanding Voting Eligibility in American History

- Page ID

- 73490

Whose Right to Vote?

Voting is the most visible manifestation of democracy. Ostensibly, our system provides you a periodic opportunity to make a meaningful choice among candidates for a variety of offices. The idea that the general public should have the right to choose its leaders is a fairly recent one. Indeed, through much of our history, the majority of the public did not have this fundamental right. You should be familiar with the major steps through which eligibility to vote expanded in American history.

In what is widely considered today to be a colossal mistake, the Constitution does not mention voting qualifications, and it does not even guarantee a right to vote—although it is implied because we have the elected House of Representatives. Instead, the issue of voting qualifications was left to the individual states, and the eligibility to vote itself required various Constitutional amendments to be extended beyond propertied White men. The fact that the Founders did not positively assert a fundamental right to vote has shaped the course of American history and undercut the democratic nature of America’s political system.

Property Qualifications and Voting Eligibility

During the colonial period, some states required religious qualifications to vote, but state legislatures abolished those by 1810. Initially under the Constitution, states permitted only White males with property to vote. Property qualifications to vote was a practice America inherited from England, where such restrictions had been in place since the Middle Ages. The idea behind these restrictions was that only men who freeheld enough property could be determined to be independent—that is, not dependent on others as women, servants, slaves, free Blacks, children, and others were, and that they simultaneously possessed a stake in society. During the Constitutional Convention, Governor Morris of New York advocated that just such a property restriction be written into the Constitution. Morris said:

“Give the votes to people who have no property, and they will sell them to the rich who will be able to buy them…The time is not distant when this country will abound with mechanics and manufacturers who will receive their bread from their employers. Will such men be the secure and faithful guardians of liberty?” (3)

According to Madison’s notes, Benjamin Franklin countered Morris, and spoke passionately in favor of the common man. The Constitution did not mandate a property qualification to vote and left it to the states. At America’s founding, each state differed in the amount of property a man must own in order to qualify as a voter. In some states, 90 percent of White men were disqualified because they did not own enough property. But the early republic was growing quickly through immigration and natural increase, and there was a spirit that celebrated liberty, extolled the common man, and reveled in partisan struggle. New states like Missouri and Illinois joined the union without voting restrictions on adult White men. Property qualifications for White men to vote were dropped across the board by the 1850s, usually due to parties competing in the state legislatures. Thus, the United States possessed universal White male suffrage by the eve of the Civil War.

Race and Voting Eligibility

The United States fought the Civil War over the issue of slavery and the political struggle over whether slavery could be extended outside the South. Before the war, Abraham Lincoln did not support African-American voting rights. During the war, he changed his mind and favored extending the right to vote to Black soldiers in the Union army and to “very intelligent” Blacks. (4) After the North won that bloody conflict, there was an opportunity to pass an amendment to the Constitution to establish a positive right to vote. Instead, the Republicans in Congress passed the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870, which simply established a prohibition on the states without firmly establishing a right to vote. The Fifteenth Amendment says that “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude…” Their intention in passing the amendment was to give the vote to newly freed Black men, so they could defend the rights of their families in the political environment after the Civil War. However, since the amendment was written in broad language, it theoretically applied to all non-White males.

Southern Democrats bitterly opposed expanding voting rights to Blacks. Democratic Senator Garrett Davis of Kentucky said that African Americans were “in a condition of brutalized, ferocious, and ignorant barbarism,” and could therefore not take their place alongside Whites as citizens empowered with a voice in government. (5) In the decades after passage of the Fifteenth Amendment, Southern Whites took numerous measures–discussed in chapter 68–to ensure that Blacks did not actually vote. Due to that suppression, by the 1950s voter turnout among African Americans in the former Confederacy was approximately 50 percentage points lower than turnout for Whites. That gap was essentially eliminated in the three decades after passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which is a testament not only to the efficacy of legislation, but also to the Civil Rights Movement generally. (6)

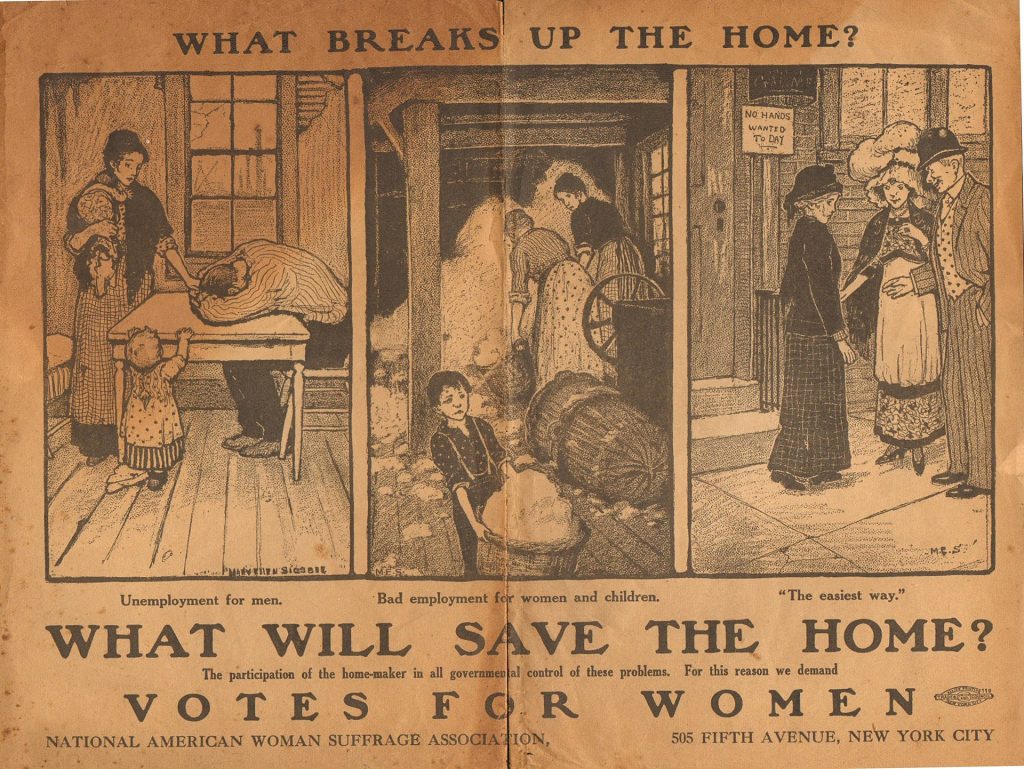

Sex and Voting Eligibility

While the Fifteenth Amendment was being discussed, feminists argued that the right to vote ought to be extended to women as well, but they lost that fight. Feminists finally won fifty years later when the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified in 1920. It was a long, difficult struggle to secure the right to vote for women. The Seneca Falls Declaration in 1848 was the first national call for women’s suffrage. Organizations like the National American Women Suffrage Association employed tactics such as petitions, marches, speeches, court cases, debates, picketing at the gates of the White House, and prison hunger strikes. The 1917 protest at the White House gates involved over 5,000 women during its two-year run and has been described as “the first high-visibility nonviolent civil disobedience in American history.” (7)

Women’s suffrage came first in the West. In 1869, Wyoming allowed women to vote, and Utah followed suit the next year. Colorado passed a women’s suffrage bill in 1893, and Idaho joined the effort in 1896. There are many reasons why this happened first in Western territories and states. Historian Beverly Beeton emphasizes pragmatic rather than ideological reasons. In Wyoming, for instance, one of many factors was that state legislators thought that enfranchising women would “advertise the territory to potential investors and settlers,” because it only had 9,000 residents at the time. (8) Western states and territories were largely being founded after the Fifteenth Amendment passed, and many people wondered why it made sense to deny educated White women the right to vote when it had just been extended to uneducated former male slaves. Western suffrage movements also benefitted from the work that was being done by East Coast national organizations. The fact that women were able to vote in Western states helped the national suffrage movement, and it did not result in the ills that suffrage opponents claimed, such as the corruption of women by politics, the destruction of relationships with husbands, the neglect of children, and so forth. This is often the case with social change, whether it be gay marriage, racial integration of the military, or women’s rights.

Poll Taxes and Access to the Ballot

Age and Voting Eligibility

Incarceration and Voting Eligibility

A felony conviction and incarceration typically negate your ability to vote in most states. Interestingly, prior felony conviction and incarceration do not abrogate your freedom of speech, freedom of religion, right to join a group, right to marry, etc. According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, only Maine and Vermont allow convicted felons to vote while serving their sentences. For many years, Utah joined Maine and Vermont, but the voters of Utah ended that practice through a ballot initiative in 1998. In sixteen states, felons automatically get their voting privileges reinstated upon release. In eleven states, “felons lose their voting rights indefinitely for some crimes or require a governor’s pardon in order for voting rights to be restored, face an additional waiting period after completion of sentence (including parole and probation) or require additional action before voting rights can be restored.” (15) The Brennan Center for Justice refers to disenfranchisement laws as “relics of our Jim Crow past,” and that they “send the message that the voices of individuals returning to their communities don’t count.” (16)

It is interesting to reflect that while the Constitution went into effect in 1789, the United States did not have legally recognized adult suffrage for all men and women, regardless of race, until ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920, passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, and the extension of the right to vote to 18-year-olds in 1971. We might also note that voting is not an inalienable right recognized by the Constitution, as witnessed by the way that we strip the ability to vote from incarcerated men and women. What, then, does democracy mean in America when the most basic democratic act is so tenuously grounded in our law and history?

What If. . . ?

What if we amended the Constitution to establish an affirmative right to vote? Representatives Mark Pocan and Keith Ellison introduced such an amendment, which reads:

A Constitutional Amendment for an Explicit Right to Vote

”SECTION 1. Every citizen of the United States, who is of legal voting age, shall have the fundamental right to vote in any public election held in the jurisdiction in which the citizen resides.

SECTION 2. Congress shall have the power to enforce and implement this article by appropriate legislation.” (16)

References

- League of Women Voters.

- Iowa Journal of the Constitutional Convention, 1857, State Historical Society of Iowa, Des Moines, Iowa, 241-242; Gallaher, 173-174, 186. Quoted in Libby Jean Cavanaugh, Opposition to Female Enfranchisement: The Iowa Anti-Suffrage Movement. Master’s Thesis, Iowa State University, 2007. Page 15.

- Michael Waldman, The Fight to Vote. New York: Simon and Schuster. Page 22. This section draws heavily on Waldman’s excellent book.

- Eric Foner, “Freedom’s Dream Deferred,” American History. 50 (4): December, 2015.

- Allan J. Lichtman, The Embattled Vote in America. From the Founding to the Present. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2018. Page 83.

- Niraj Chokshi, “Where Black Voters Stand 50 Years After the Voting Rights Act was Passed,” The Washington Post. March 3, 2015.

- Michael Waldman, The Fight to Vote. New York: Simon and Schuster. Page 122.

- Beverly Beeton, “How the West Was Won for Woman Suffrage,” in Marjorie Spruill Wheeler, One Woman, One Vote. Rediscovering the Woman Suffrage Movement. Troutdale, OR; Newsage Press. Pages 99-116.

- Alexander M. Bickel, “Congress and the Poll Tax,” The New Republic. April 24, 1965.

- Bruce Ackerman and Jennifer Nou, “Canonizing the Civil Rights Revolution: The People and the Poll Tax,” Northwestern University Law Review. 103(1): 63-148. Page 65.

- Quoted in Ari Berman, Give Us the Ballot. The Modern Struggle for Voting Rights in America. New York: Farrar, Strus and Giroux, 2015. Page 17.

- National Museum of American History.

- Geraldine Sealey, “Too Young to Vote?” abcnews.com. March 10, 2004. Kelsey Piper, “Young People Have a Stake in Our Future. Let Them Vote,” Vox. September 20, 2019.

- National Youth Rights Association.

- National Conference of State Legislatures. October 14, 2019.

- The Brennan Center for Justice.

- FairVote.org.

Media Attributions

- Votes Women © Mary Ellen Sigsbee Fischer is licensed under a Public Domain license