10.2: Chapter 63- Incorporation or Nationalization of the Bill of Rights

- Page ID

- 73504

Does the Bill of Rights, which is where many of your civil liberties are located, protect you only against infringements by the United States government, or does it protect you against your state and local government as well? The answer is that it protects you against abuses from all levels of government, but this has not always been true. The important case is Barron v. The Mayor of Baltimore (1833). John Barron owned a wharf in the eastern section of Baltimore harbor. Beginning in 1815, Baltimore began a series of construction and paving projects that involved the diverting streams. As it happened, the diverted streams came out into the harbor immediately next to Barron’s wharf. By 1822, Barron sued Baltimore city and the mayor because the newly diverted streams were causing silt to build up to such a degree that ships were no longer able to access his wharf. Barron’s lawsuit rested on the Fifth Amendment, which says that no one’s property may be seized for public use without due process and just compensation. Since there was neither due process nor any compensation for damage to the economic viability of his property, Barron felt he would win. However, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Baltimore, saying that the Bill of Rights protects people from actions of the central government, not state and local actions. The Supreme Court said that Barron needed to seek redress from the Maryland state constitution, but there was no such provision in that document that would help Barron. The significance of the Barron decision is that it set up a dual system of civil liberties: a national one to protect individuals from the central government, and widely varying standards to protect people from state and local government abuses. Therefore, your civil liberties depended upon where you lived and what level of government you faced.

After the Civil War, the Fourteenth Amendment seemed to correct the imbalance defined in Barron by saying that no state “shall abridge the privileges and immunities of citizens of the United States.” However, the Supreme Court did not interpret the privileges and immunities clause as a corrective to Barron. Instead, in the late nineteenth century, the Court began incorporating the Bill of Rights protections using the Fourteenth Amendment’s due process clause instead of the privileges and immunities clause. The due process clause says that states may not “deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” Many people see this as an odd way of nationalizing the Bill of Rights and other broad liberties, but there it is. (2) In specific cases, the Court incorporated individual Bill of Rights protections into the due process clause by limiting states’ ability to infringe upon them. The Court did this selectively and patiently, waiting for individuals to challenge their state when it infringed on specific civil liberties. The process of incorporation lasted into the early twenty-first century as cases came to the Court.

You do not need to know all of the incorporation cases, but you should be familiar with the following three examples. They not only illustrate the concept of incorporation, but also are cases whose impacts are still felt today.

Important Incorporation Cases

Mapp v. Ohio (1961)–This case involved the Fourth Amendment’s provision that people be protected from unreasonable searches and seizures. The Amendment says that search warrants need to be issued by judges upon probable cause and that warrants need to be specific rather than general. Under the Barron precedent, the Fourth Amendment only protected you against federal officials. State and local officials were regulated by state constitutions, which varied in how much they protected people from unreasonable searches and seizures.

On May 23, 1957, three Cleveland, Ohio police officers came to Ms. Dollree Mapp’s house looking for a male suspect whom they believed was related to a bombing incident as well as an illegal gambling outfit. Ms. Mapp called her lawyer and refused to let the officers in because they did not have a warrant. Three hours later, the officers, whose ranks had grown to seven, forcibly entered Mapp’s house, roughed her up and handcuffed her, and proceeded to search the house. They did not find the man, bomb-making equipment, or gambling paraphernalia, but they did find that Mapp possessed “obscene materials,” for which she was arrested on the spot. Mapp was convicted but appealed her conviction all the way to the Supreme Court, which ruled in her favor and incorporated the Fourth Amendment into the Fourteenth. State and local authorities now face the same obligation that federal officials do to respect the Fourth Amendment. Additionally, the Mapp case also applied the exclusionary rule to state and local police: any evidence they gather in violation of the Fourth Amendment must be excluded from the defendant’s trial.

Gideon v. Wainwright (1963)–This case deals with the Sixth Amendment’s provision that criminal defendants have a right to counsel for their defense. Following the Barron precedent, the Court had long held that indigent defendants facing federal charges would be provided a public defender, but states could set their own rules for defendants facing state criminal charges. Later, the Supreme Court ruled that defendants charged with a capital offense must be provided a lawyer if they could not afford one. Still, the vast majority of criminal defendants do not face either federal or capital charges.

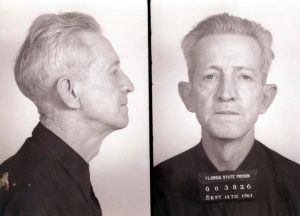

In 1961 Clarence Earl Gideon was a 51-year old drifter who had been in and out of trouble with the law since he had run away from home at age sixteen. Gideon was arrested in Panama City, Florida for breaking into a poolhall and stealing some money and alcohol. At his trial, he asked the judge for a lawyer to defend himself against the charges but was denied because he was charged with neither federal nor capital offenses. Without a lawyer, he was convicted and sentenced to five years in prison. While incarcerated, Gideon made use of in forma pauperis, a Supreme Court procedure that waives the filing fees and other requirements for indigent petitioners. He wrote a letter to the Supreme Court asking them to take his case. The Court granted certiorari and appointed Abe Fortas, a well-respected Constitutional lawyer and future Supreme Court justice himself, to represent him. The majority ruled in Gideon’s favor, and remanded the case back to Florida where Gideon was given a retrial with a public defender. Gideon’s lawyer was able to show that the state of Florida could not meet its burden of proving beyond a reasonable doubt that Gideon had done the crime, so he was released. The result of the case is that the Sixth Amendment was incorporated into the Fourteenth, and criminal defendants must be appointed lawyers if they cannot afford one. This is extremely important, because approximately 80 percent of all criminal defendants are too poor to hire their own lawyer. (3) Public defenders are clearly overworked and underpaid—earning below minimum wage in some cases—but defendants without any legal assistance are at a huge disadvantage when faced with state power in a court of law.

McDonald v. Chicago (2010)–The most recent incorporation case occurred in 2010 and involved the Second Amendment’s guarantee of the right to bear arms. In 1983, Chicago banned the sale and ownership of handguns. This ban was similar to those in other cities, such as Washington, D.C. In 2008, the Chicago Police Department refused Otis McDonald, a 76-year old retired maintenance engineer, permission to own a handgun. McDonald wanted a gun to protect himself in his crime-ridden neighborhood. Supported by gun rights groups and joined by three other petitioners, McDonald sued the city of Chicago.

Meanwhile, in the same year the Supreme Court struck down Washington D.C.’s gun ban in a case known as The District of Columbia v. Heller (2008). Despite the language in the Second Amendment clearly predicating the right to bear arms in the context of a “well-regulated militia,” the Court narrowly ruled in Heller that the Second Amendment confers an individual right to own and carry weapons. However, the Heller case did not have immediate implications for other city and state gun laws because of D.C.’s special status as a federal district. InMcDonald v. Chicago(2010), the Supreme Court decided (5-4) in McDonald’s favor and incorporated the individual right to bear arms into the Fourteenth Amendment. The ruling, therefore, made it applicable to states and cities across the United States. The Court also said that the individual right to bear arms was subject to regulation. In the D.C case, Justice Antonin Scalia wrote: “Like most rights, the right secured by the Second Amendment is not unlimited. . . [N]othing in our opinion should be taken to cast doubt on longstanding prohibitions on the possession of firearms by felons and the mentally ill, or laws forbidding the carrying of firearms in sensitive places such as schools and government buildings, or laws imposing conditions and qualifications on the commercial sale of arms.” He was also clear that the list of restrictions he just mentioned was not “exhaustive.” (4) However, in the case of New York State Rifle and Pistol Association Inc. vs. Bruen (2022), the conservative majority on the Court struck down a 109-year-old New York state law requiring people to show cause for why they needed to carry a handgun in public. Effectively, this decision struck down laws in a number of states where a quarter of the U.S. population lives. It also shifted the gun debate to the issue of “sensitive places” where bearing arms could still be restricted. Is a court of law a sensitive place? A legislative chamber? What about a grocery store or a political rally? Due to incorporation, future decisions of the Court on these matters will apply to all states.

References

- Gideon v. Wainwright (1963).

- Scholar Daniel A. Farber writes, “Picking the Due Process Clause as the home for fundamental rights was something of a historical accident, but not completely ungrounded…The [privileges and immunities clause] and the Ninth Amendment would have given a much stronger basis for protecting fundamental rights from state governments.” See his Retained by the People. New York: Basic Books, 2007. Pages 76-77.

- Alexa Van Brundt, “Poor People Rely on Public Defenders Who Are Too Overworked to Defend Them,” The Guardian. June 17, 2015.

- District of Columbia, et al. v. Heller (2008).

Media Attributions

- Gideon © Florida State Prison is licensed under a Public Domain license