10.4: Chapter 65- The Law and Politics of Religious Freedom

- Page ID

- 73506

America’s Religious Schizophrenia

On first glance, the words of the First Amendment appear to be clear: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” These words, however, have given rise to at least as many arguments as those dealing with freedom of speech. With so many cases, it’s difficult to understand what the legal status of religion is in the United States, particularly when it clashes with other values such as civil rights.

Much of the problem stems from America’s cultural schizophrenia about religion’s place in public life. We seem to have conflicting traditions. While America has a long tradition of people fleeing religious persecution, some of the groups who fled religious persecution moved rather quickly to establish their own “official” religions or to set up theocracies. As Americans, we have a long tradition of opposing religious intolerance. Indeed, Thomas Jefferson advocated for a “wall of separation” between church and state. We also have a long tradition of invoking God’s blessing and making other religious displays at public events. We also have a long train of religious and political leaders who, like Christian evangelist Franklin Graham, attribute our misfortunes to God’s disapproval of our sinful ways. Simultaneously, we have embraced science and empiricism. Reconciling these often-conflicting traditions has not been easy.

Establishment and Free Exercise of Religion

The First Amendment’s treatment of religion consists of two related phrases. One is called the establishment clause because it restricts Congress’ ability to legislate regarding “an establishment of religion.” The second phrase, “or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,” is referred to as the free exercise clause. What do these phrases mean when taken together? Clearly, the founders did not want America to become a country like England and its Church of England, with an established official religion. Interestingly, the only time religion is mentioned in the Constitution is when it says, “No religious Test shall ever be required as a Qualification to any Office or public Trust under the United States.” This forbids the government from requiring that elected or appointed leaders be from a particular religion or even that they believe in God at all.

An important milestone in how the Constitution interpreted the establishment clause developed in Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971). Rhode Island was subsidizing private religious schools for money spent on teacher salaries, and Pennsylvania was reimbursing private religious schools for money spent on teacher salaries. In both states, these provisions were part of larger, general state statutes that supported elementary and secondary education. The Court struck down these practices as a violation of the establishment clause. And in doing so, it set forth the Lemon Test for government laws concerning religious organizations:

- The statute “must have a secular legislative purpose.”

- Its “principal or primary effect must be one that neither advances nor inhibits religion.”

- It must not foster “an excessive government entanglement with religion.” (2)

Beyond this, the Supreme Court has generally ruled the following: that the government should not show a preference for a particular religion, not support the propagation of religion, and not endorse religious symbols on public facilities unless all other kinds of expression are also supported or unless there is a secular justification for the symbols. The Court has also allowed “incidental” religious displays on public property—think “In God We Trust” on our money—that are unlikely to do much to forward the cause of a particular religious tradition. The court has allowed tax dollars to support students going to religiously affiliated colleges and universities, as well as to support some aspects of elementary and secondary religious school attendance, such as purchasing books and tests and providing transportation.

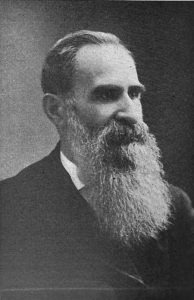

In other areas, the Court has allowed government to restrict religion in some instances, but not in others. In Reynolds v. United States (1878), the Court upheld a federal law banning polygamy, even though George Reynolds was married to more than one wife because it accorded with his religious beliefs. This case was particularly important because the Court made the distinction between religious beliefs, which the government could not regulate, and religious practices, which the government could regulate. Without this distinction, the Court argued, people could hide all sorts of outrageous and/or dangerous behavior behind the curtain of religion. More recently, the Court ruled in Goldman v. Weinberger (1986) that an Orthodox Jew in the Air Force could be prohibited from wearing a yarmulke. Finally, in Employment Division v. Smith (1990), the Court ruled against Native Americans who had been fired and denied state unemployment benefits because they used peyote as part of an off-duty religious ceremony. However, in West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette (1943), the Court ruled that a compulsory flag salute law violated the religious rights of Jehovah’s Witnesses, whose religious practices prohibit them from worshipping graven images. And in Wisconsin v. Yoder (1972), the justices ruled that because of the Amish’s religious beliefs, they were not bound by state compulsory school attendance laws.

In 1993, Congress passed the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA), which was designed to reverse the Smith decision and other restrictions on religious practice. The RFRA prohibited state and federal governments from limiting a person from exercising their religion unless it was in the government’s compelling interest to do so and unless the regulation in question is the least restrictive way to achieve the government interest. In 1997, the Supreme Court struck down part of the RFRA as intruding too greatly on state powers. The case involved the Catholic Archdiocese in San Antonio Boerne, Texas, which wanted to expand a 1920s-era church building. The town of Boerne denied the building permit based on a local ordinance forbidding construction on historic district buildings. The Court sided with the town. (3) In response, Congress passed the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act of 2000, which gives religious organizations special land-use considerations.

The RFRA continues to be used as a defense against government intruding on religious practices. For example, it was central to a Supreme Court decision forbidding the government from banning the use of sacramental tea that contained schedule 1 illegal drugs. (4) The Supreme Court’s conservative majority has looked very favorably on religious expression, even when it conflicts with other values. Consider the Court’s recent decisions:

- Since Missouri funds playground construction and maintenance at public schools, it must also fund playground construction and maintenance at church schools as well. (5)

- The Colorado Civil Rights Commission displayed bias against religion in its treatment of a wedding cake baker who refused on religious grounds to bake and decorate a cake for a same-sex wedding. (6)

- The religious owners of privately held companies can be exempt from the Affordable Care Act mandate that their health insurance cover contraception for their employees. (7)

- Stores cannot have dress codes that forbid employees from wearing any kind of head scarf because it would discriminate against employees who wear head scarves for religious reasons. (8)

- Governments can own and maintain religious statues on public land—in this case a cross commemorating soldiers who died in World War I—if they have existed for a long time and if their display serves secular purposes as well as religious ones. (9)

And yet the Court also ruled that. . .

- A Muslim death row inmate could not have an imam present when he was given lethal injection, even though Alabama routinely allows Christians in that situation to have clergy with them. (10)

- President Trump’s travel-ban that was clearly motivated by anti-Muslim animus does not violate the establishment clause if it is officially justified on national security grounds. (11)

Overall, the current Supreme Court is more pro-religion now than it has been in modern memory. For example, professors Lee Epstein and Eric Posner calculated that while the Court ruled in favor of religious interests 58 percent of the time during the period from 1985 to 2005, since then the Court has ruled in favor of religious interests 86 percent of the time. (12) In Carson v. Makin (2022), the Court ruled that Maine’s private school voucher program must allow parents to use the taxpayer-funded vouchers at religious schools.

Religion in Public Schools

A great example of the First Amendment’s establishment clause and the free exercise clause intersecting is the vexing problem of religion in public school. In the 1960s, the Court limited some religious expression that could legally occur in public schools. In Engel v. Vitale (1962), the Court struck down a New York law that required students to recite daily the following prayer: “Almighty God, we acknowledge our dependence upon Thee, and we beg Thy blessings upon us, our parents, our teachers and our country.” Despite the fact that the prayer was nondenominational and that students with permission from parents could opt out of reciting the prayer, the Court ruled that the practice constituted an establishment of religion. The next year, in Abington School District v. Schempp (1963), the Court struck down a Pennsylvania school’s daily practice of having a student read the Lord’s Prayer and a Bible passage over the school’s PA system. In this case, the Schempp’s were church-going Unitarians who objected to the practice. At the time of the Engel and Abington cases, organized prayer in public schools was not as common as many would believe today. Around 70 percent of public schools did not have public prayer in the early sixties. (13)

Progressives and conservatives alike have grossly distorted these and other decisions for their own political reasons. Some on the far left have argued, because this is the reality they want to see happen, that the Court has banned prayer from public schools. Similarly, to mobilize conservative voters over a false issue, some on the far right have argued that the Court has indeed banned prayer from public schools. The Supreme Court has not banned prayer or other religious expression from public schools. The table below delineates the forms of religious expression that are and are not allowed in public schools. (14)

| Students in Public Schools Can: | Students in Public Schools Cannot: |

|---|---|

| Pray any time they want, so long as it is not disruptive. | Be asked to recite a prayer by school officials. |

References

- Cheryl K. Chumley, “Franklin Graham on Coronavirus Crisis: ‘Man Has Turned His Back on God.’” Washington Times. April 6, 2020.

- Lemon v. Kurtzman(1971).

- City of Boerne v. Flores(1997).

- Gonzales v. O Centro Espírita Beneficente União do Vegetal (2006).

- Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia v. Comer(2017).

- Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission(2018).

- Burwell v. Hobby Lobby, Inc.(2014).

- EEOC v. Abercrombie and Fitch Stores, Inc. (2015).

- American Legion v. American Humanist Association(2019).

- Jefferson S. Dunn, Commissioner, Alabama Department of Corrections v. Domineque Hakim Marcelle Ray(2019).

- Trump v Hawaii(2018).

- Nina Totenberg, “The Supreme Court is the Most Conservative in 90 Years,” National Public Radio. July 5, 2022.

- Susan Jacoby, The Age of American Unreason. New York: Pantheon Books, 2008. Page 184.

- Developed from: American Jewish Congress, et al,, “Religion in Public Schools: A Joint Statement of Current Law.” April, 1995. No Author, “Religion in the Curriculum,” Anti-Defamation League. No Date. Washington Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction, “Students’ Rights: Religion and Religious Practice,” No date.

- Ian Millhiser, “The Supreme Court Hands the Religious Right a Big Victory by Lying About the Facts of a Case,” Vox. June 27, 2022. Ariane de Vogue, Tierney Sneed, and Chandelis Duster, “Supreme Court Says Maine Cannot Exclude Religious Schools from Tuition Assistance Programs,” CNN. June 21, 2022.

Media Attributions

- George Reynolds © Published by 'Young Men's Mutual Improvement Association' is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Coach Kennedy Leading Students in Prayer © Bremerton School District is licensed under a Public Domain license